What else is spreading along with the virus? Sleep problems. Widespread lockdowns have blurred the boundaries between work and rest, sociality and domesticity, lucidity and somnolence. The alertness induced by suggestions of viral menace and societal breakdown wrestles with the drowsiness brewed by tightened stay-at-home orders. After all, it is hard for a fleshy body to respond to viruses and sovereignty at the same time.

Those are the things occupying my mind when entering the exhibition “Resistance of the Sleepers” at UCCA Dune, curated by Ara Qiu with a lineup of young artists from China and beyond. The works are scattered across seven cave-like circular galleries, including outdoor ones. The diverse practices of ten artists highlight the contradiction between biological imperatives of sleep and the seemingly unstoppable 24/7 nature of global capitalism.

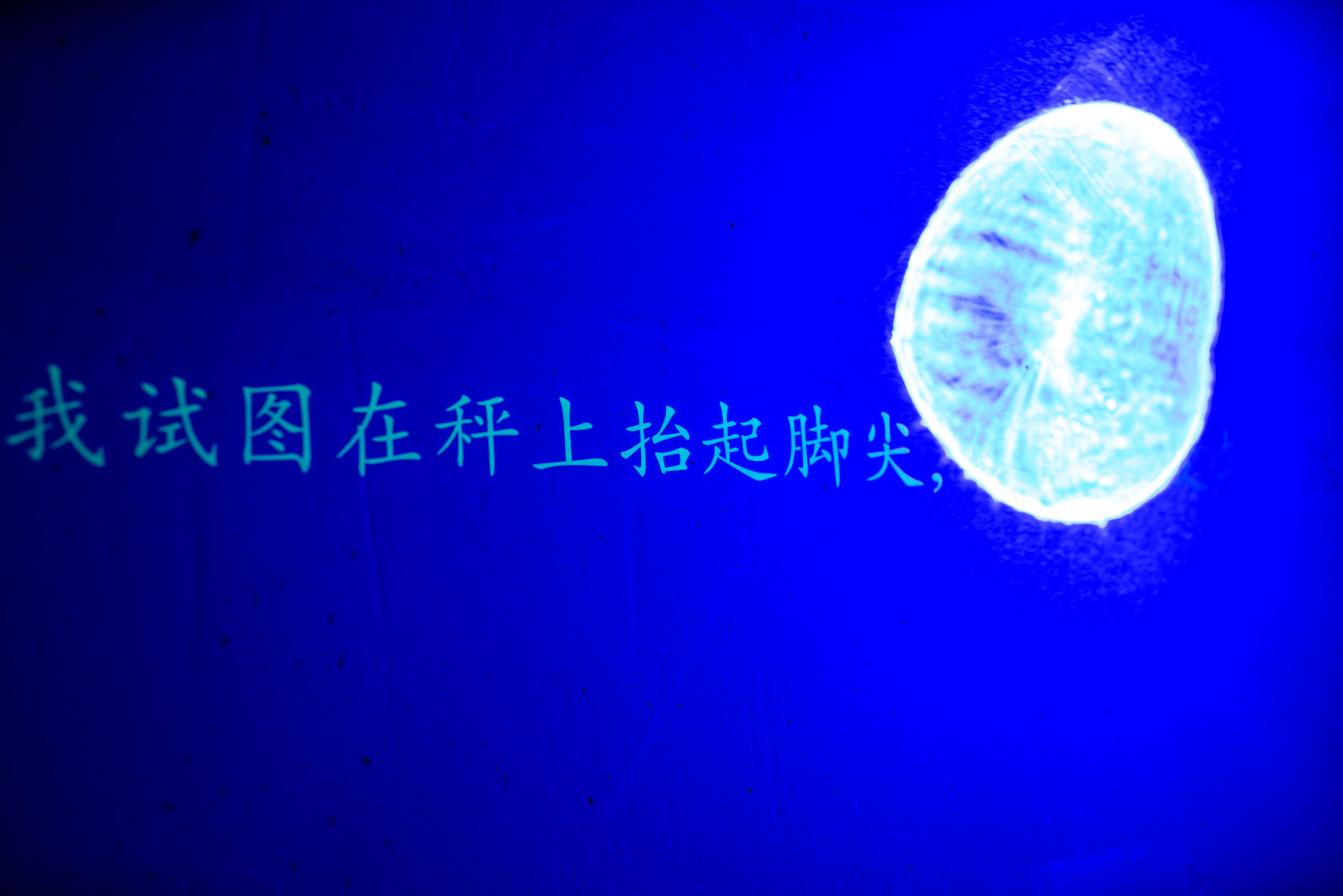

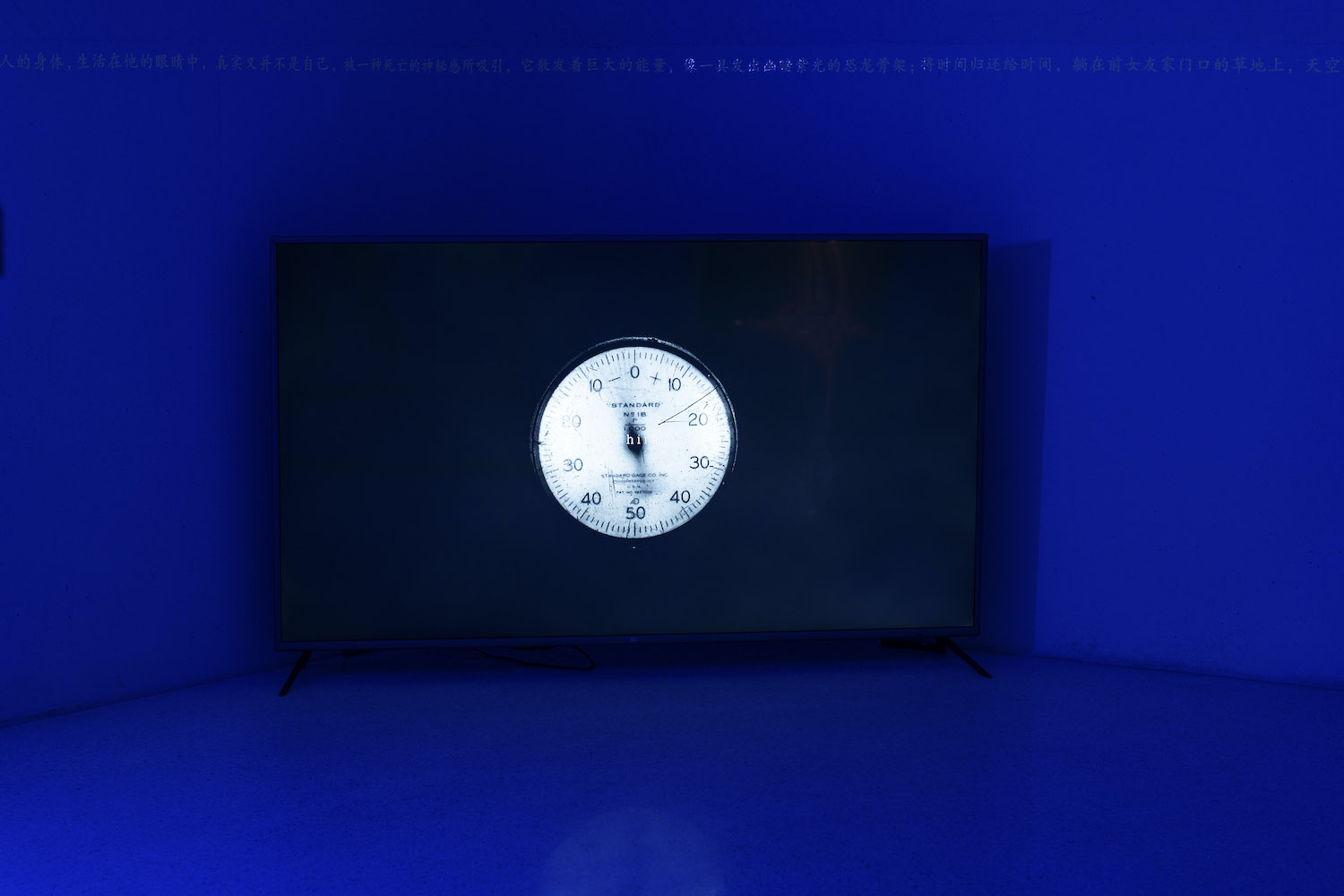

The exhibition begins in the first gallery with Hiraki Sawa’s evocative black-and-white film Sleep Machine II (2011), in which herds of sheep traverse unmanned nocturnal streets and alleys. The film works in tandem with Shen Linghao’s kinetic installation, in which a projected blue light moves across stream-of-consciousness texts printed on walls. In the central gallery, Ana Montiel’s dreamy color field prints from “The Translucent Mind Series” (2020) provide a visual undertone for the whole exhibition — even if they might be a tad too lighthearted compared to other works. One of her prints replaces the large skylight on the roof, projecting colorful shades of light that change with the position of the sun.

Three semi-outdoor galleries facing the ocean temper the artworks with sunlight and seascapes. Zhang Ruyi’s biomorphic concrete being, circumscribed in a fish tank with live scavenger fish, suggests a Lovecraftian nightmare leaking into the daytime. Zhang Kerui carved her dreams onto copper plates with minimalistic strokes. The copper plates sit outside and will slowly decay from the eroding effect of the Pacific breeze. Chang Yuchen’s two-channel video installation juxtaposes footage of her sleeping with the text of a monologue. A eulogy for her lost lover, it is beautiful, disturbing, and sustains a gravitational force like a black hole. I almost couldn’t finish watching it. Li Shuang’s I want to sleep more but by your side (2018–19) is the result of two years of living and working in the Chinese city of Yiwu, a robust trading center for small commodities. The video is a poetic essay on love and pain in an age of hypermobility.

The last gallery, more of a white-cube space, hosts the work of Fei Yining and Katie Paterson. Fei’s short animation New Clear War (2018) is a lovely animal fable that pokes at the politics behind clean energies. Her experiments with 3-D printed reliefs covered with flesh-like resin emit an enchanting witchy glamour. Paterson encodes the day-night cycles of the solar system’s planets, plus Earth’s moon, in nine clocks. Their visual austerity contrasts interestingly with Fei’s dazzling maximalist aesthetics.

In a way, the architecture, too, is part of the show. Designed by OPEN Architecture and carved into sand dunes, it reminds me of Kafka’s unfinished short story “Der Bau” (The Burrow), in which an anthropomorphic animal meticulously prepares its burrow for an imaginary enemy attack.

Overall, the exhibition is a coherent thematic investigation into the contemporary politics of sleep, paying legible homage to Jonathan Crary’s wonderful polemic 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. It is hard to omit the fact that the museum is located within the Aranya Gold Coast, a gated community appealing to buyers from Beijing, some three hundred kilometers away, with a full array of service workers recruited locally. In this Westworld-esque community we encounter the sleeper’s version of Hegelian master-slave dialectics. The slave, who has nothing to lose, can well enjoy a sound, deep sleep. The master, meanwhile, suffers from insomnia and the fear of losing his life or property during sleep, for it is his most defenseless state. Slumber was a gift to the underdog, brought by pennilessness and ample melatonin from exhaustive labor. The asymmetry of sleep between the strong and the weak is also conjured in Hobbes’s Leviathan, which argues for the necessity of a social contract as opposed to the “state of nature.” However, the social contract, at the end of the day, does more good on the master’s side and maintains the quality of his sleep. Such threads are left unaddressed, but may also be somewhat beyond art’s remit. After all, art is subject to the same systems that keep us up at night.