Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993), a morality tale about the wonders of technology at the end of the twentieth century, was born around the rise of Silicon Valley’s now three-decade-long project of wowing and improving society. How fictional John Hammond amazed by “disrupting” the zoo, Garrett Camp did for cabs and Jeff Bezos did for the purchase of books and, then, everything. If any tyrannosaur has escaped its paddock, nobody in charge is making any real effort to switch the mainframe off. Raphael Hefti’s body of work is situated firmly in this same conceptual territory — much more tactile and visually rough than the sleekness we expect of apps, but born from the same deceptively simple place of disrupting normal, probably unnoticed, processes and exhibiting the wonder that may follow.

His exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, “Salutary Failures,” encompasses five rooms and in its titling points to a mission of positive events resulting from perversions of production chains. The spaces each encompass a major installation of a certain type and do not flow into each other, feeling more like five separate project shows than what is Hefti’s largest institutional exhibition to date. The third houses five large steel ingots on the floor that are softly rounded and cracked like cartoons or melted minimalism in the vein of a gnawed Walter De Maria. Over the past eight years these sculptures have been subject to temperature changes simulating five thousand years of aging. The title, Dr. Satler: So, what are you thinking? Dr. Grant: We’re out of a job. Dr. Malcolm: Don’t you mean extinct? (2020), is lifted from Jurassic Park’s script and points to Hefti’s interest in both eonic timeframes and ambition in his art and the real-world personal effects of technology’s constant and uncaring replacement of natural processes and human employment.

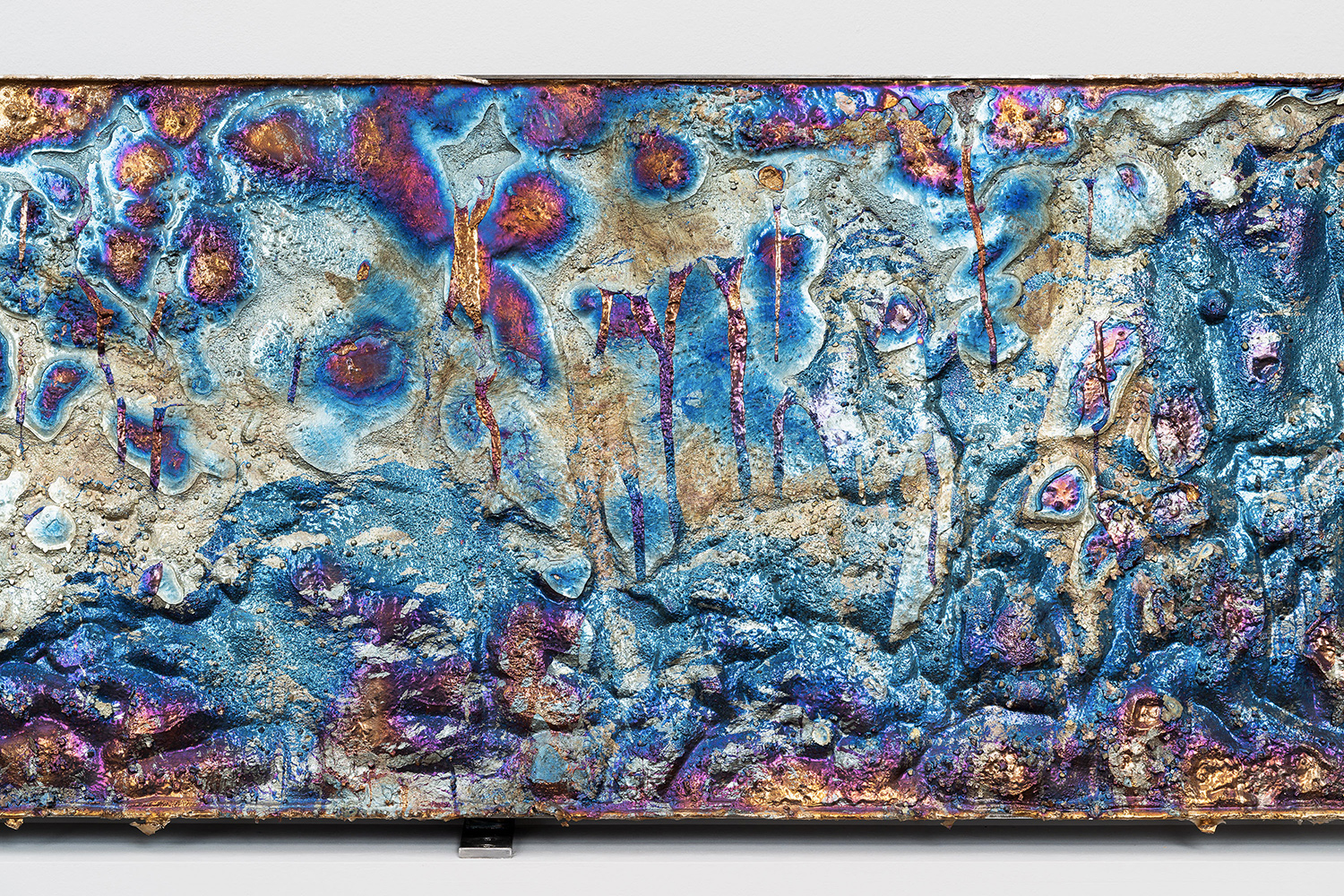

The Sun is the Tongue, the Shadow is the Language (2020) is the largest installation, consisting of blocks of recycled casting sand splashed and waterfalled with aluminum flash. Walking through it is like traversing a gentle labyrinth, and its repurposed forms recall Chichén Itzá or Michael Heizer’s City (1972–). Here again Hefti finds geometric beauty and grandeur in the foundry. This project opens on to a room housing a thin, six-meter-long “painting,” Polycrystalline Horticulture (2020), formed by oxidized bismuth and so heavy it had to be leaned against the wall on a fitted pedestal. It’s stunning. The solidified poured metal glistens in iridescent blues, fuchsias, and golden oranges; it appears that the process of its creation is one of inevitability. As with De Maria and Heizer, Hefti also understands that scale can circumvent a viewer’s logic and lead to feelings of the sublime. Why show the world a single dinosaur when you can create a fully automated island resort theme park?

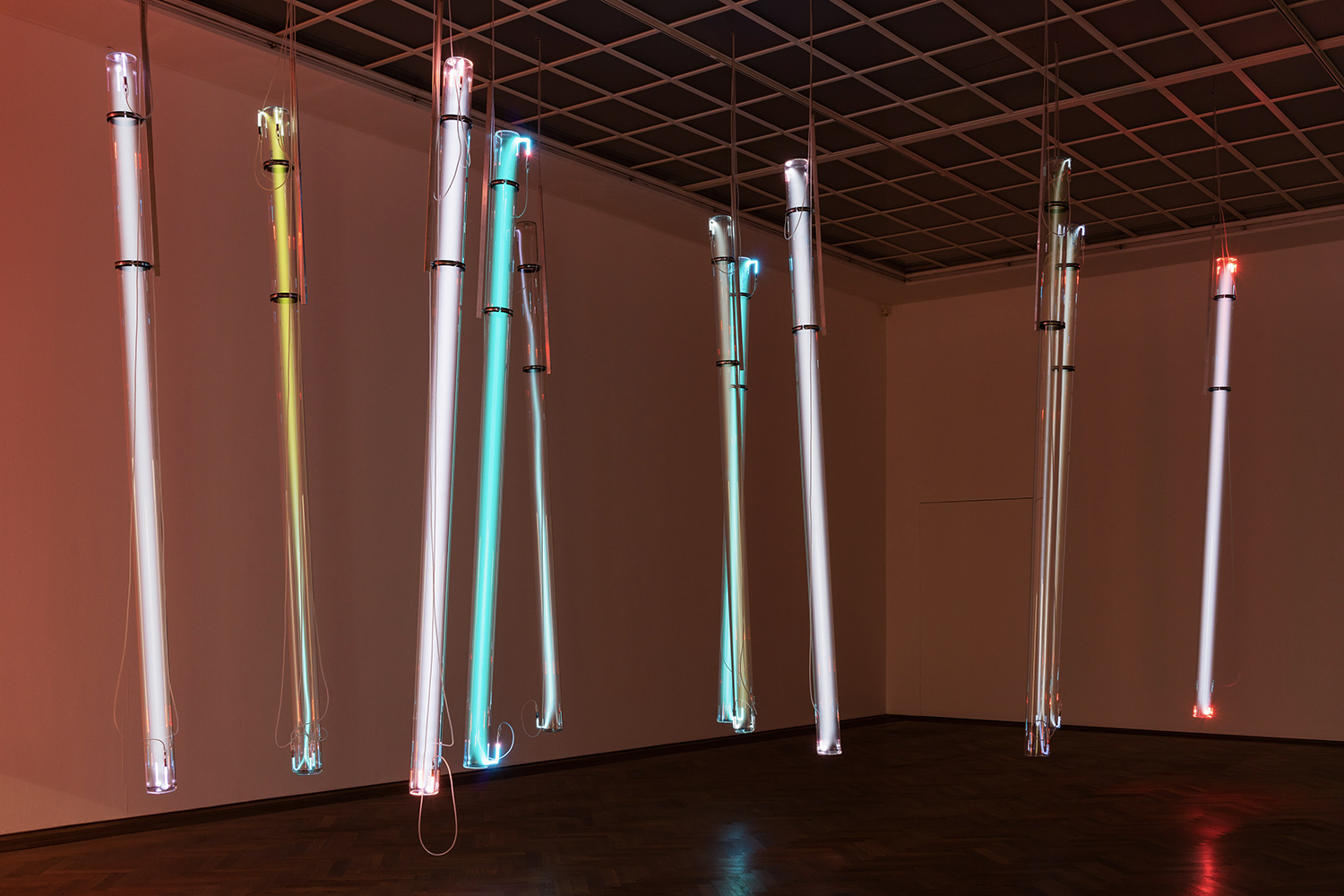

The final room renders the perception of transcendence inescapable. Fifteen custom neon tubes, thick like saplings and four meters long, hang in clusters from the dark room’s ceiling. The series, Message Not Sent (2020), mixes noble gases (neon, argon, krypton) into new chemistries of colored light: sci-fi baby blue, pale purples, and electric cotton-candy pinks. The tubes’ thickness allows one to witness what is normally hidden in this typically commercial process: the gases mixing in space, their tones changing, cloudlike, reacting to applied voltage. Like most of Hefti’s work it’s a simple trick. Choose a non-art process, scale it up, and rejig the established recipes for an unexpected outcome. Badly executed magic is like the uncanny, triggering a guttural rejection. Well-executed magic, even when you know it’s an easy illusion, yanks the spiritual to the now, leaving one probing the world for further beauty and alchemy at every chance, praying for a decent sequel.