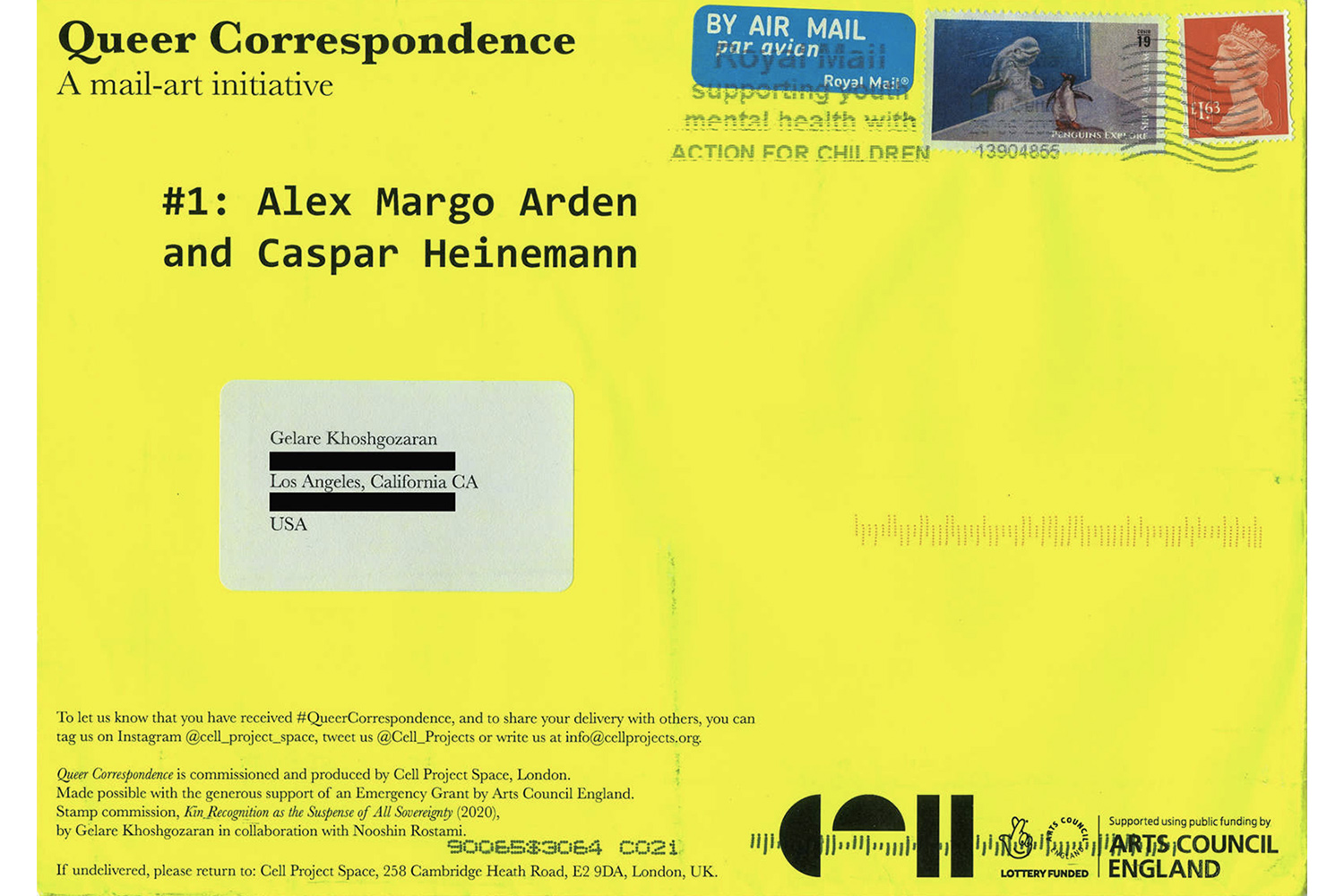

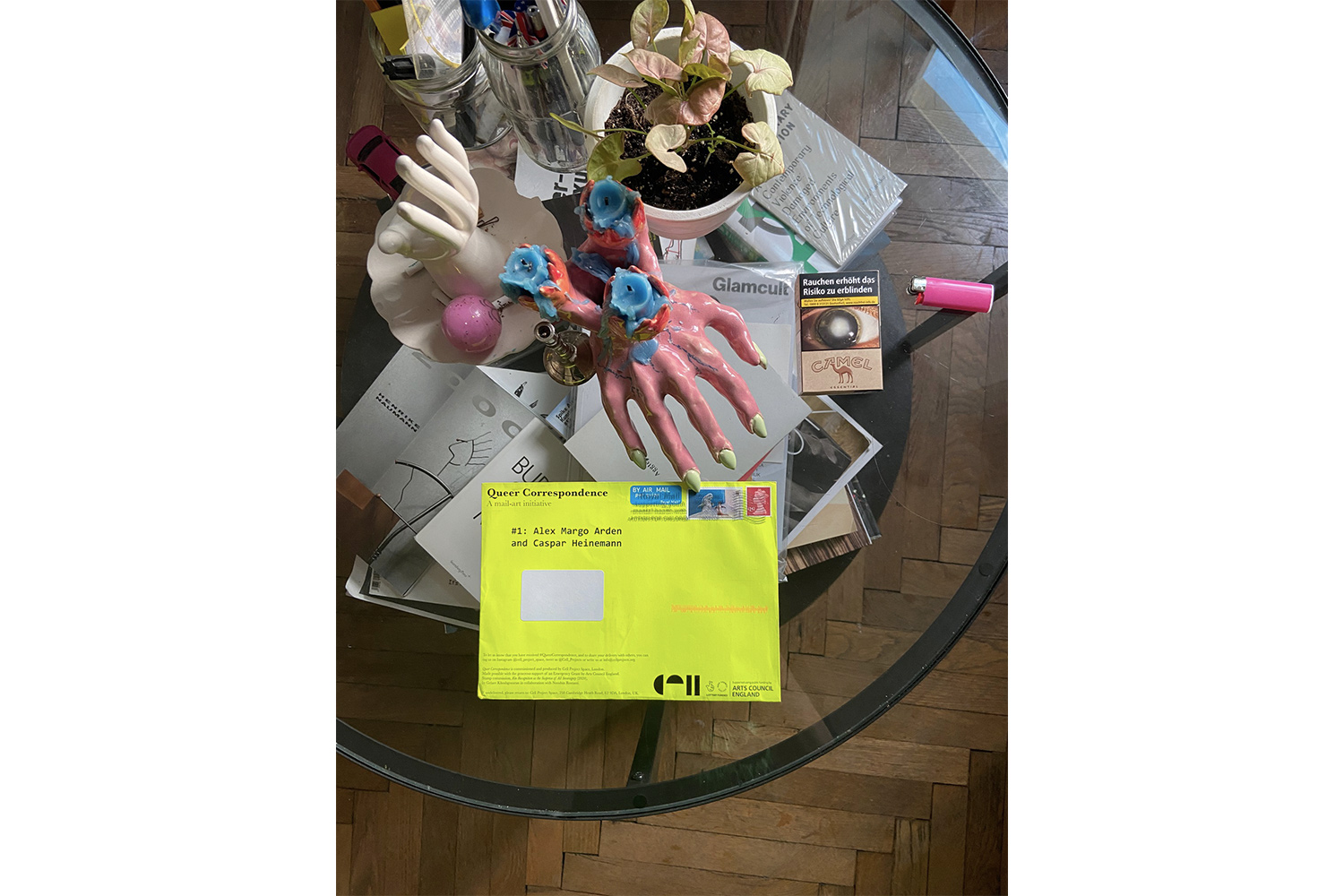

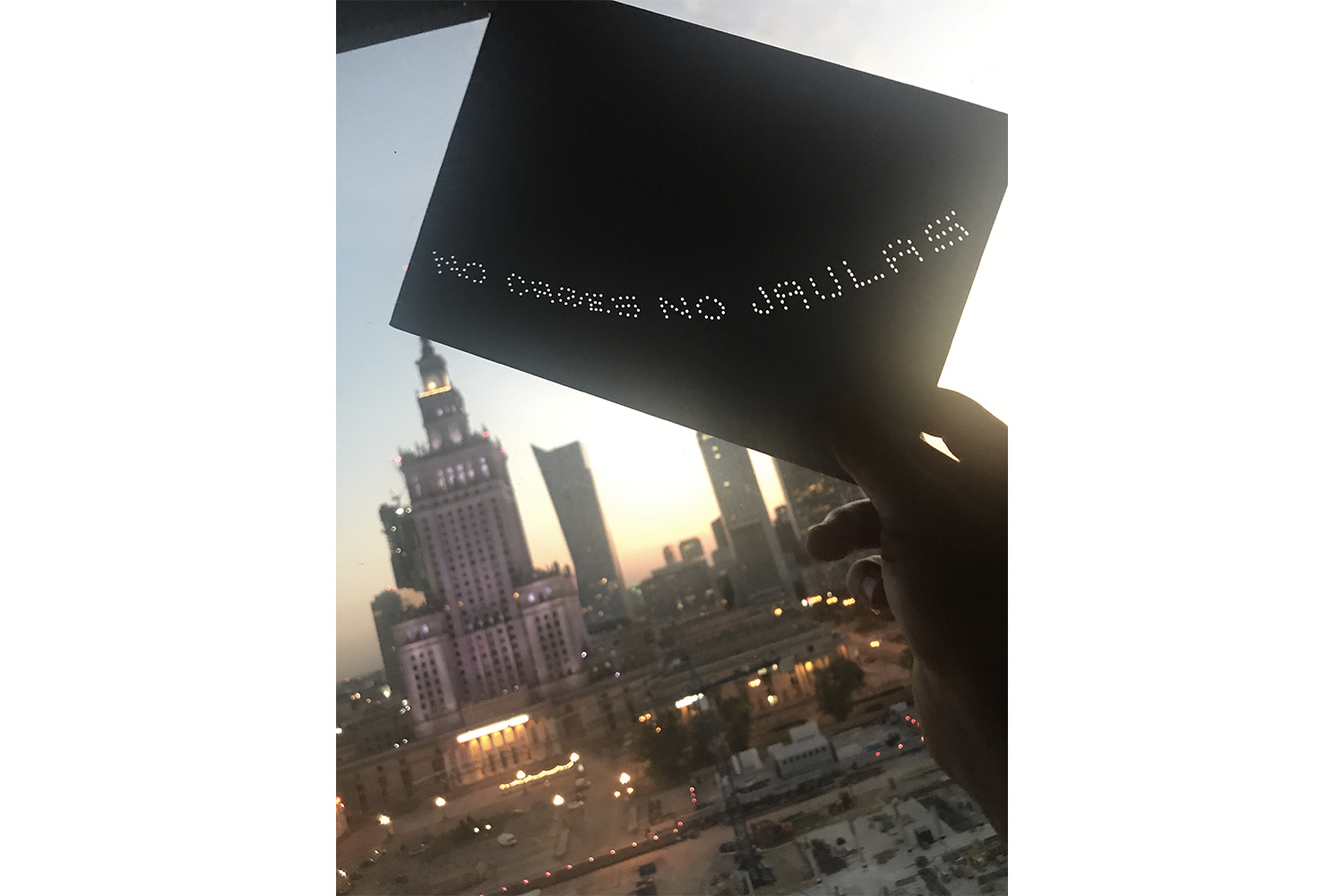

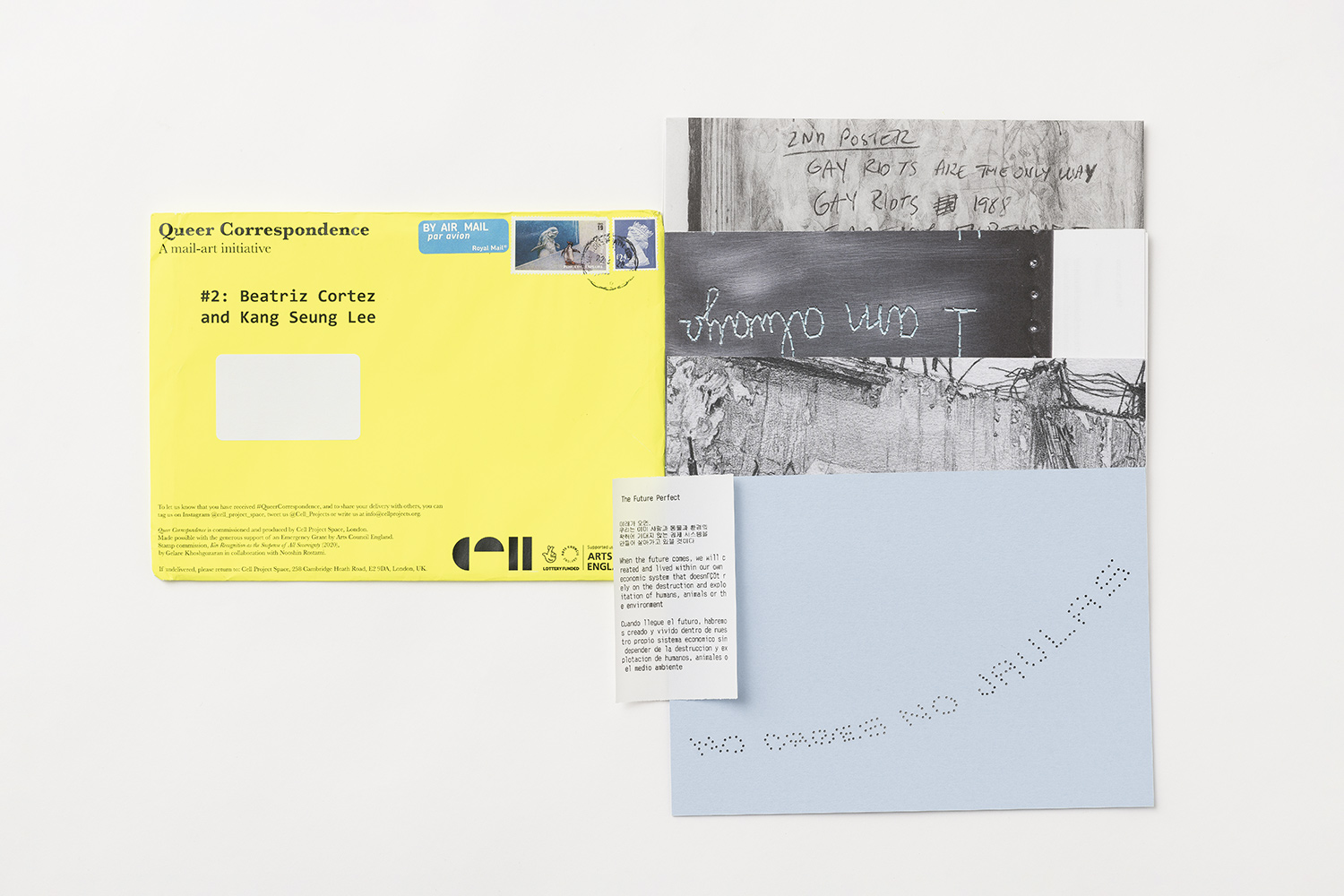

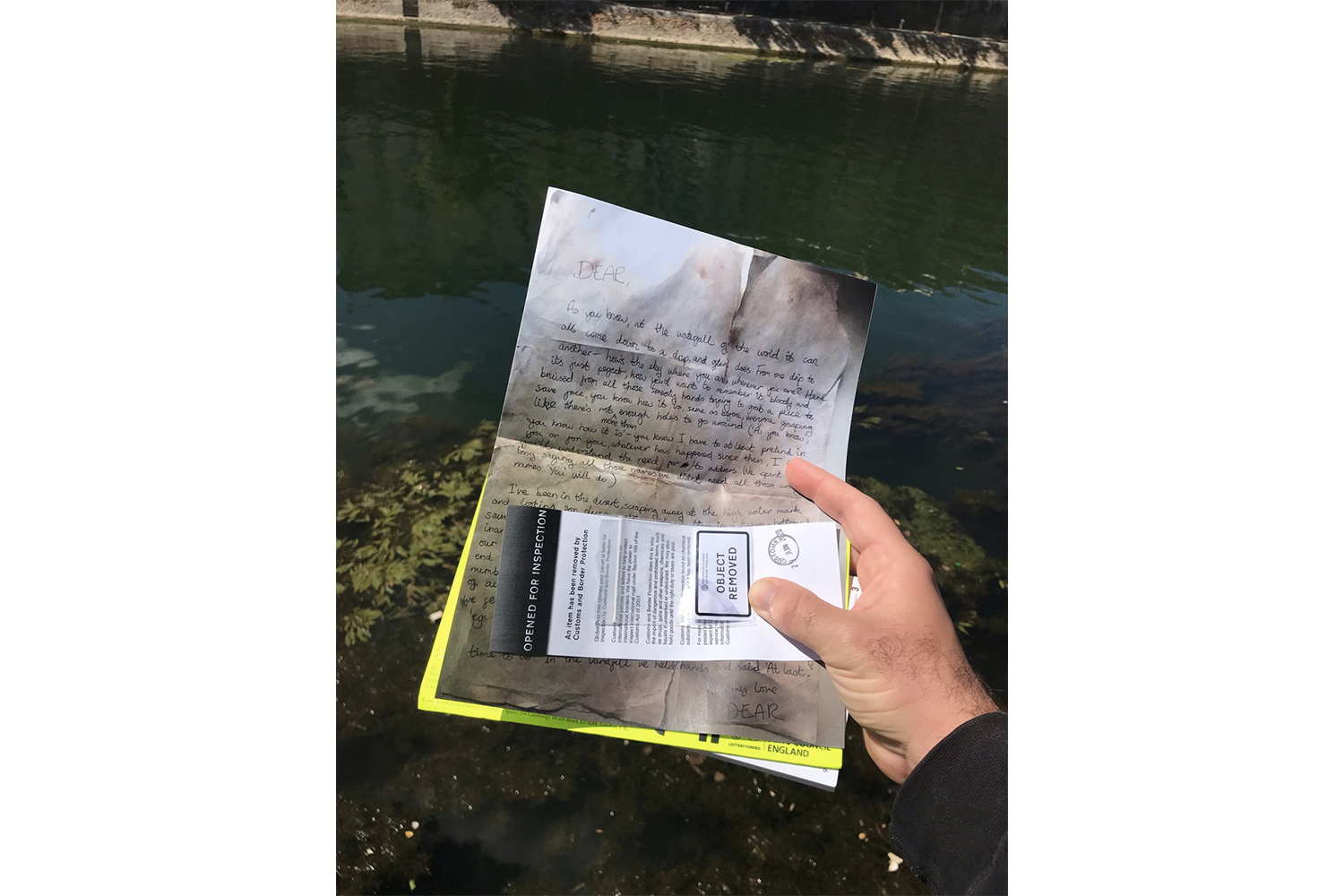

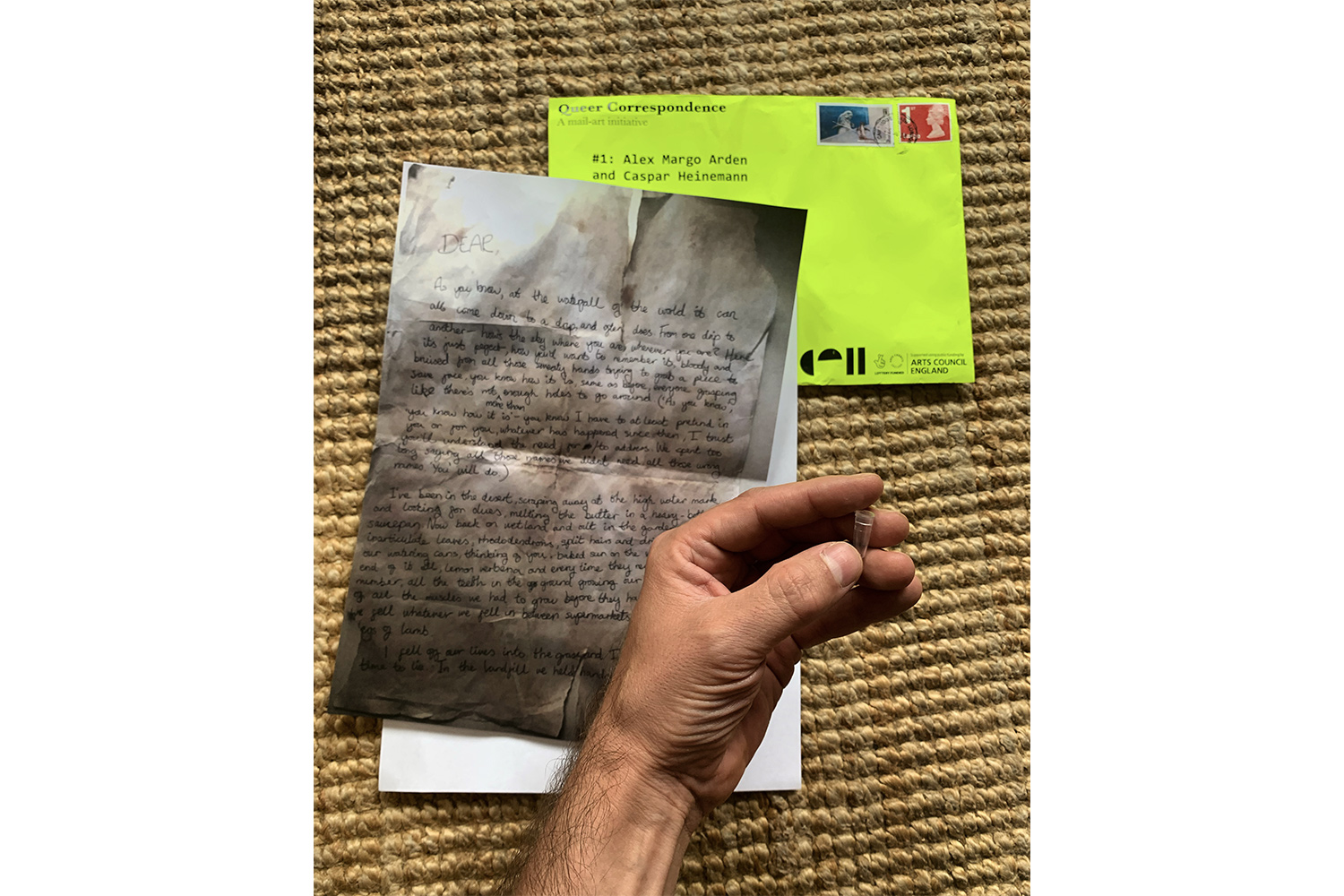

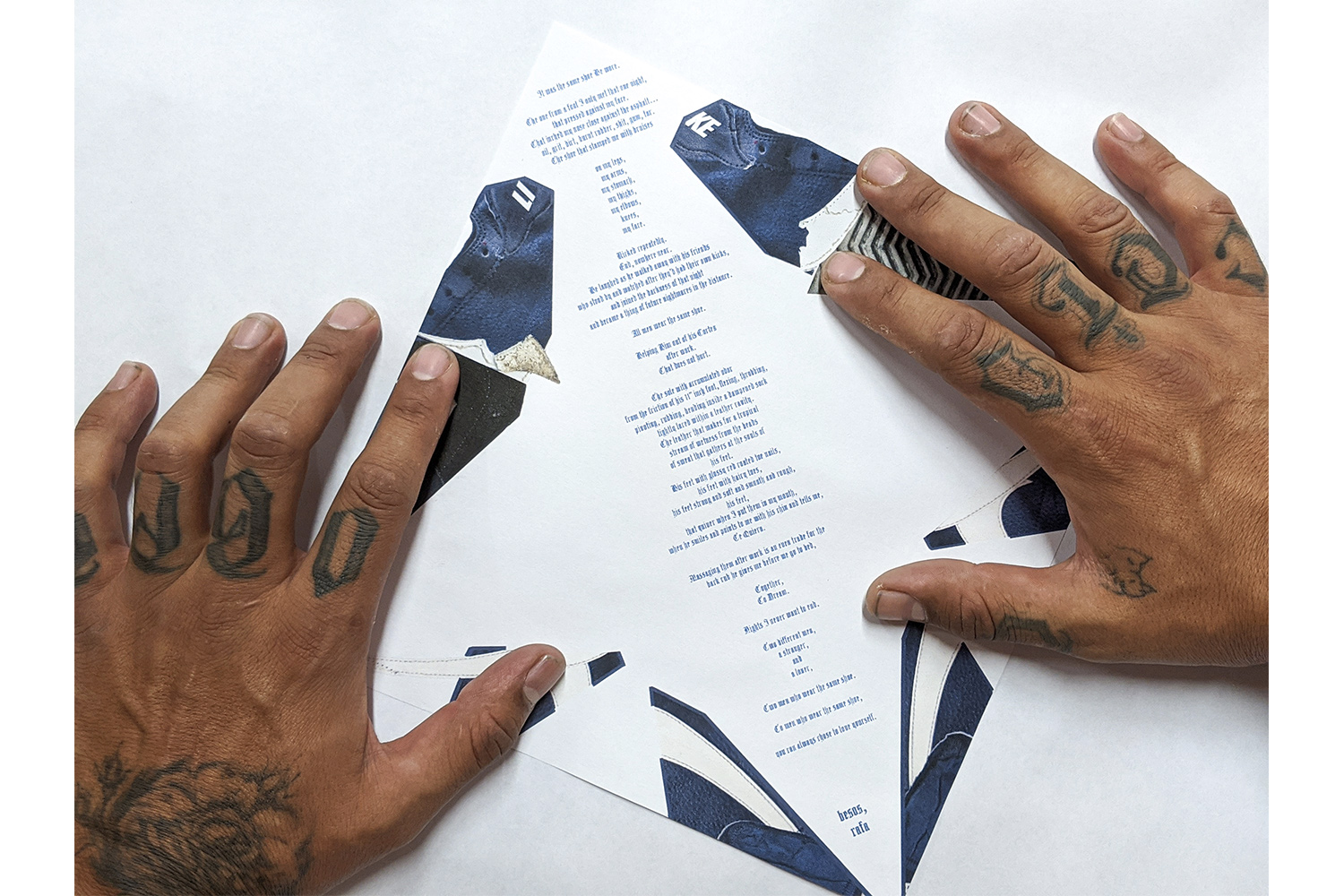

As part of our ongoing investigation of contemporary practices, Flash Art reached out to Cell Project Space, one of the most experimental independent galleries in East London, to discuss their mail-art initiative “Queer Correspondence.” Consisting of monthly commissions between June and December 2020, artists and writers are invited to initiate conversations that will establish connections between queer families. These exchanges between peers, friends, loved ones, close community members, and even absent addressees — borne through writing, poetry, photographs, and other 2-D forms — are efforts to catalyze intimate and sometimes invisible gaps in queer culture today. Letters have historically served as gestures of solidarity, a means of making and preserving connections when spatial proximity is not possible due to geographic distance and/or social and political barriers. At a time when discourse and interaction is restricted, the use of mail art as an analog form of artistic and discursive production seeks to both underscore and minimize the distances between us. With each letter, “Queer Correspondence” embarks on a literal and figurative journey, making possible the crossing of borders, the traversing of private and public spaces, and inviting recipients into new realms of possibility.

Flash Art editor Eleonora Milani invited Eliel Jones, associate curator at Cell Project Space, to talk about his vision for queer community, and how art as correspondence can build bridges within the art world and beyond.

Eleonora Milani: “The indeterminate spaces of possibility”: that’s how you define the interstices in which this project is located, which intends to give voice and recognition to the queer community via alternative forms of artistic production. After all, art is always a renegotiation of possibilities. Where did the idea for this mail-art project come from?

Eliel Jones: Without wanting to sound overtly sentimental, it was born out of love. I’ve been in a long-distance relationship with my boyfriend for the past three years. When the pandemic started to really loom over us, the prospect of not being able to see each other was very difficult, but at the same time familiar to our ongoing challenge of maintaining a relationship despite our physical absence. (There is a significant geographical separation between us, which is one impediment, but there are also immaterial borders that obfuscate easy movement; and my boyfriend holds a passport deemed unfriendly to most Western countries). When something as unpredictable and unwieldy as a global pandemic takes hold of all rhythms of life, dictating the possibilities and types of encounter that are possible, it is difficult not to be thrown off balance. But slowly we managed to return to a language and set of technologies — both in the literal and affective sense — that had, until that point, helped us bridge our distance. This language and these technologies are tools for our relationship’s survival in the context of strange conditions, and in many ways “Queer Correspondence” was conceived with this spirit of longing in mind: a desire to make journeys and breach distances when many of us could not. The act of sending a letter has always propelled that intention for me so tangibly, though if I’m honest I never really thought there would come a time when the use of mail-art would feel as relevant to resurface as it does now. As a project space, it was similarly relational in the sense that it was a response to thinking about the challenge of reaching our audiences and the result of reflecting on what might be needed to help us and our community see through a moment of physical — and in many ways also emotional — isolation.

EM: How can queerness create alternative realities?

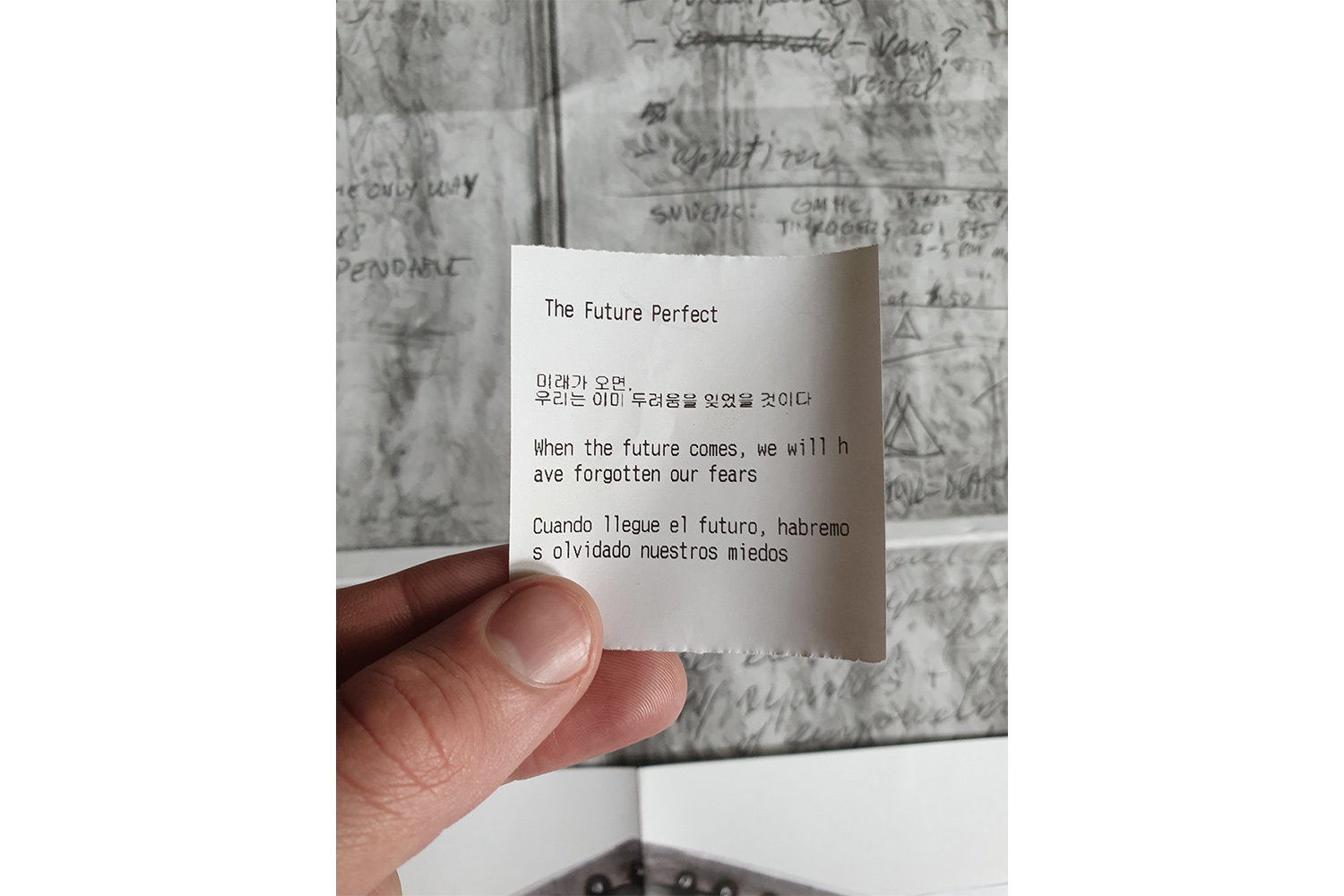

EJ: The project seeks to pay attention to queer experience — in its broadest and most inclusionary sense — as that which unleashes the tools and technologies that are infinite in their resourcefulness to make a means of life beyond the paradigmatic markers of normative existence. “Queer Correspondence” indeed deals with “possibility” in the sense that queer people — and I invoke artists Beatriz Cortez and Kang Seung Lee in saying that queerness is a mode of being that is beyond definition — have already been imagining other ways of living and doing, in order not just to survive, but to create alternative realities in the context of inhospitable environments and conditions, even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. By inviting all the contributors to exchange correspondence, the hope was to create a space for enunciating some of this world-building that is happening amongst queer folk and to share it with the community as a reminder of our ability to resist. Making the correspondences public, and extending them to anyone who wanted to receive them, was a way of fostering solidarity with the intention that some of it would be helpful in beginning to accept that, whatever we may have up until now perceived as being “normal,” should never be the same again.

EM: In Jack Halberstam’s book The Queer Art of Failure, he talks about trying to find an alternative, a “low theory” rather than following the precepts dictated by the establishment. Have his theories influenced the art community’s approach to queer issues?

EJ: I’m not sure about Halberstam’s wide influence on the art community’s approach to queer issues, but I could perhaps speak more closely to its personal impact on my own practice and its rippling effects into “Queer Correspondence” as a specific example. Halberstam has been on my close periphery since graduate school, in 2015. His work was incredibly important to me then because it really helped me hone in on the perspective that failure — “losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing” — is inherently queer; a process that opens up new and generative ways of existing that counter the expectations of an ableist, capitalist, heteronormative, white supremacist, production-orientated society. In this sense, failure is the bottomless hole that opens up new spaces of possibility for existing and understanding besides and beyond what is deemed as being normal. In this moment of crisis, I think Halberstam’s notion of failure is particularly poignant in the context of ongoing political and ideological negligence, and it comes to us as an urgent call for a refusal to accept or conform. Though many of the commissions so far have in various ways dealt with this context of precarity and oppression as their content and background, “Queer Correspondence” cannot, and does not, pretend to deal with a reckoning of this huge lack. However, it does seek to nurture the experience of uncertainty brought forward by this new pandemic as a fertile ground of possibility, placing queer joy, futurity, intimacy, friendship, forgiveness, vulnerability, and celebration as powerful antidotes. I make an emphasis on “new” because it’s important not to forget that AIDS preceded COVID-19, and in both of these global pandemics there have been political and ideological forces at play that have deemed certain lives as being, by-and-large, “expendable”. It made sense to me to return to the experienced, witnessed or passed on knowledges — many from within the queer community — that have thus far conceived possible paths to survive.

EM: This notion of failure conducing people to refuse to conform is quite interesting. In the introductory text to the project you mention in particular another seminal Halberstam book, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives, which reflects on the concepts of queer time and space. Have both concepts informed the project?

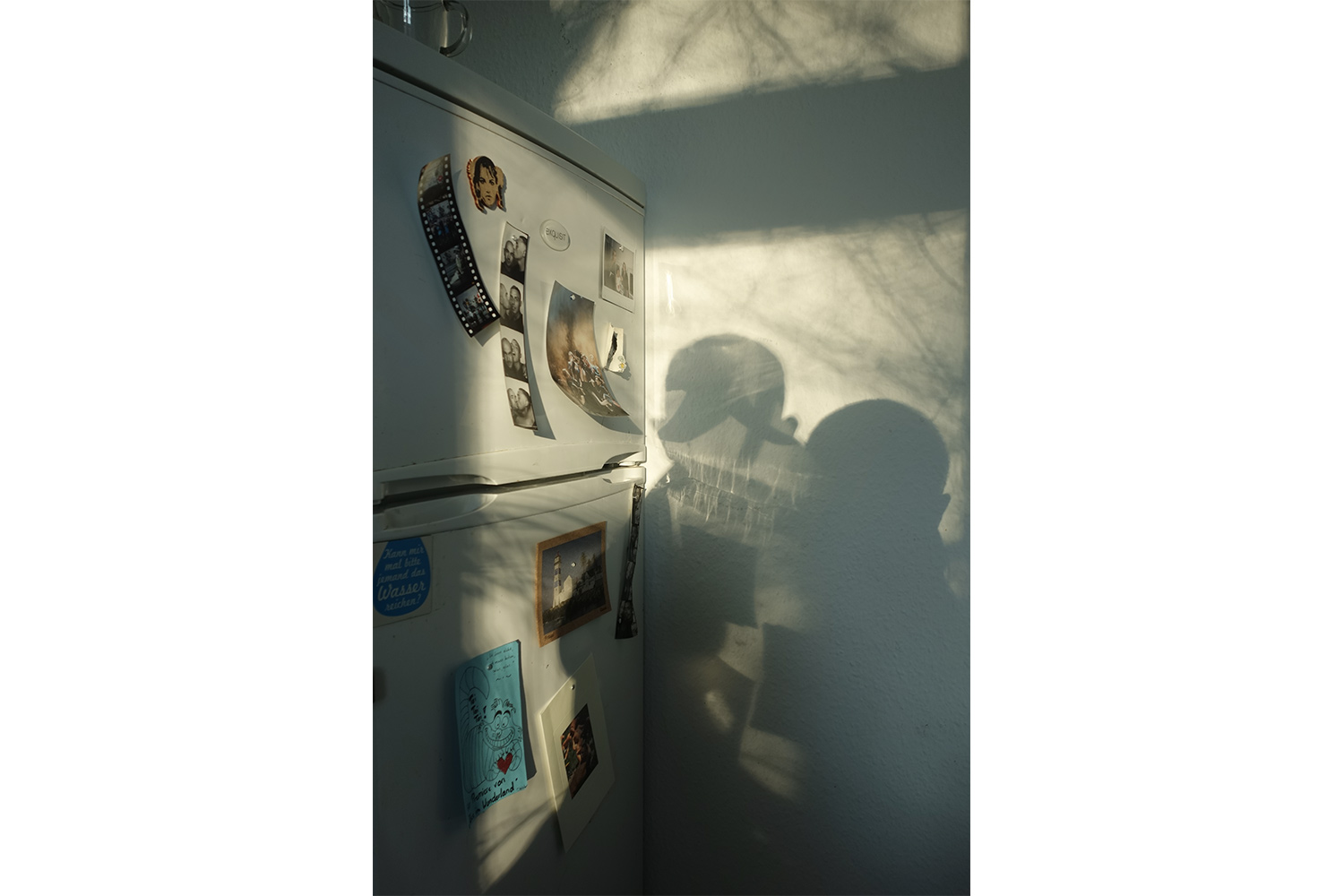

EJ: At a time when the gallery was necessarily closed, and our exhibitions program postponed, I would like to think that invoking Halberstam’s registers of queer time and place has also in some ways appeared in the project through the reach that the commissions have had outside the walls of Cell: beyond London to other regions in the UK and countries all over the world, including across Europe, as well as the US, Brazil, Russia, Thailand, India, New Zealand, Iran, and South Korea, to mention only a few of the most far-flung destinations. As a small project space in East London, “Queer Correspondence” has facilitated our engagement with places — indeed, places where we can make valuable connections with audiences and queer communities — that in many ways we have previously been unable to reach. It has also decentralized London as the main site of cultural production or engagement. I think there is something to be learnt for us both from the analogue means of mail art as well as the type of contact that the project has facilitated, whereby each recipient is reached as an individual that is being addressed. If we were to locate “Queer Correspondence” as having a site, it would be incredibly intimate and multiple. The projects have so far mostly entered people’s homes and private spaces; they’ve been shared with us as being displayed on fridges, entrances, bedrooms as well as being engaged with by children and house pets, or passed on to neighbors and friends. I think in the art world too often we speak about audiences in ways that have little consequence or effect, and now more than ever, if we want the arts to be part of the movement for resistance, we need to know who we are speaking to and how to really harness the potential of creating meaningful community. Despite the rush for organisations to load all types of programming online, I don’t believe the internet holds the only answers to creating generative space.

EM: Working-class and communities of color are disproportionately being affected by this “new normal.” Are you considering other ways to work on projects with artists in the future? Artists whose voices, ideas, and practices may be suppressed or adversely effected by the pandemic?

EJ: I don’t know if it’s so much a question of adapting to a “new normal” as it is about trying to respond to the fact that “normal” was never really an equal or shared condition of existence, but rather a risk of life that has always been greater for some than others. I think it’s helpful to remind ourselves of that because otherwise it seems like the pandemic has brought forward conditions that were previously inexistent, whilst in reality they were largely just invisible or, worse, “business as usual.” COVID-19 is a chilling reminder of how fragile the structures of survival are for a lot of people, and it has perhaps also brought it closer to home for others. This applies one hundred percent to the art world. I think we’re only starting to learn how to better hold institutions to account, and there is an immense amount of work needed to really recognise and address the precarity that many artists and cultural workers endure in order to sustain their practices. It’s something that artist Paul Maheke wrote about in his beautiful and heartbreaking open letter entitled The year I stopped making art, which so poignantly highlights the contradictions embedded in the art world’s recent propensity to make artists — particular Black, people of color, working class, queer, and disabled artists — hyper visible, yet in many ways also wholly expendable. Part of the problem is that the industry still largely operates on that which can be reaped for financial benefit, which ultimately almost always places what is to be consumed and commodified at the expense of the livelihoods of people (we are seeing this in the UK, where it didn’t take long for redundancies to be announced across big and small arts organisations as seemingly inevitable solutions to the challenges brought forward by the pandemic). The other is that the art world, despite some of our best efforts, runs on the back of colonial, racist, classist, patriarchal, capitalist, heteronormative, and ableist techniques, and this is no small thing to have to reckon with. In this sense, we cannot let the usual lip service enacted by organisations to hold up against the consequences of their decisions, particularly when they largely affect the very communities that they reportedly wish to support.

EM: That letter speaks out loud. What you say is echoed in this moving passage: “The year I stopped making art, it was before COVID-19. It didn’t take a global pandemic to end my career. I just didn’t manage to pay my tax return on time. […] The year I stopped making art, it didn’t take the wealthiest parts of the world to go in total lockdown, to be made redundant from the arts industry. It was so mundane no one noticed.” Cell Project Space seems to adopt a different approach, trying to connect community to space and art in a broader sense.

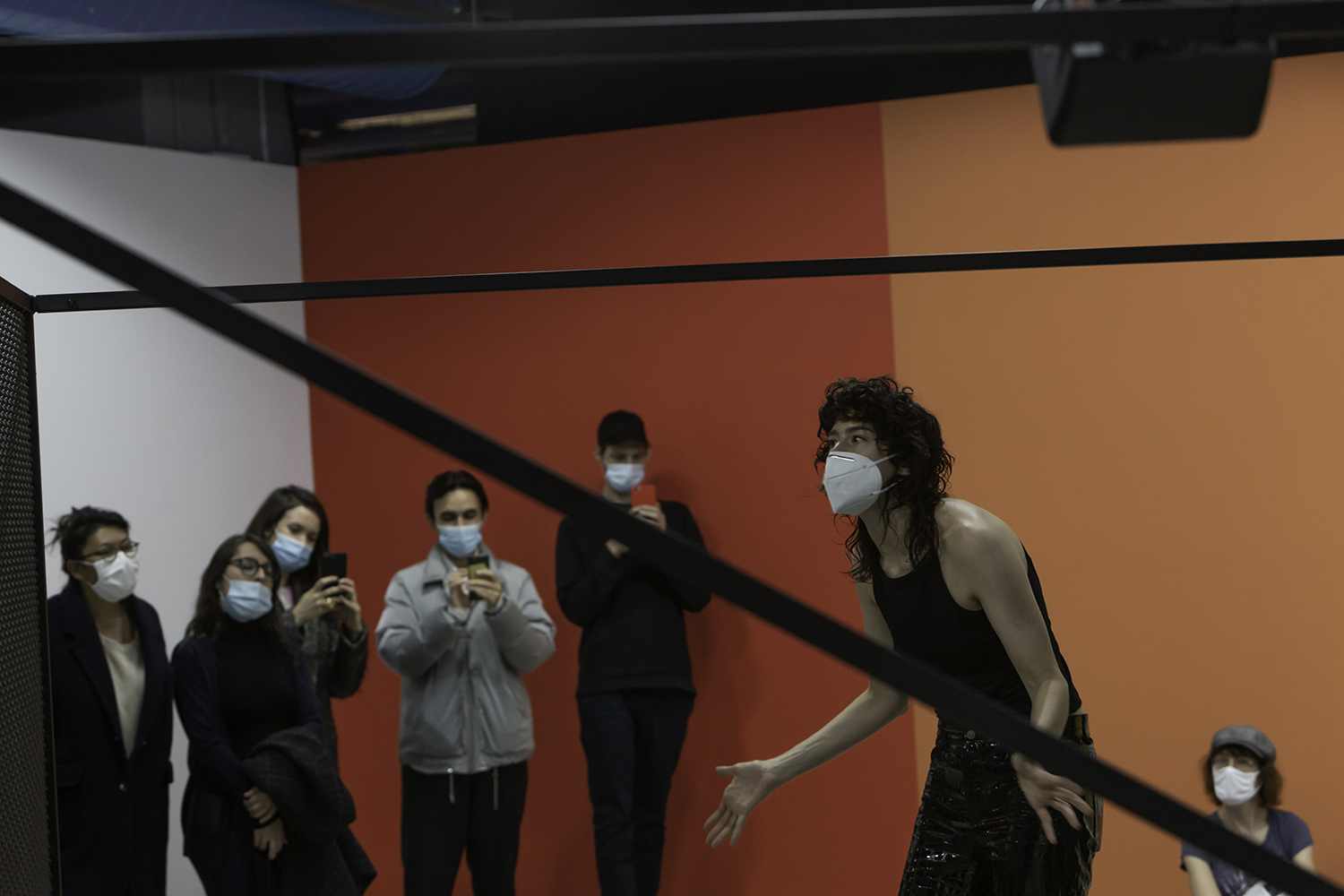

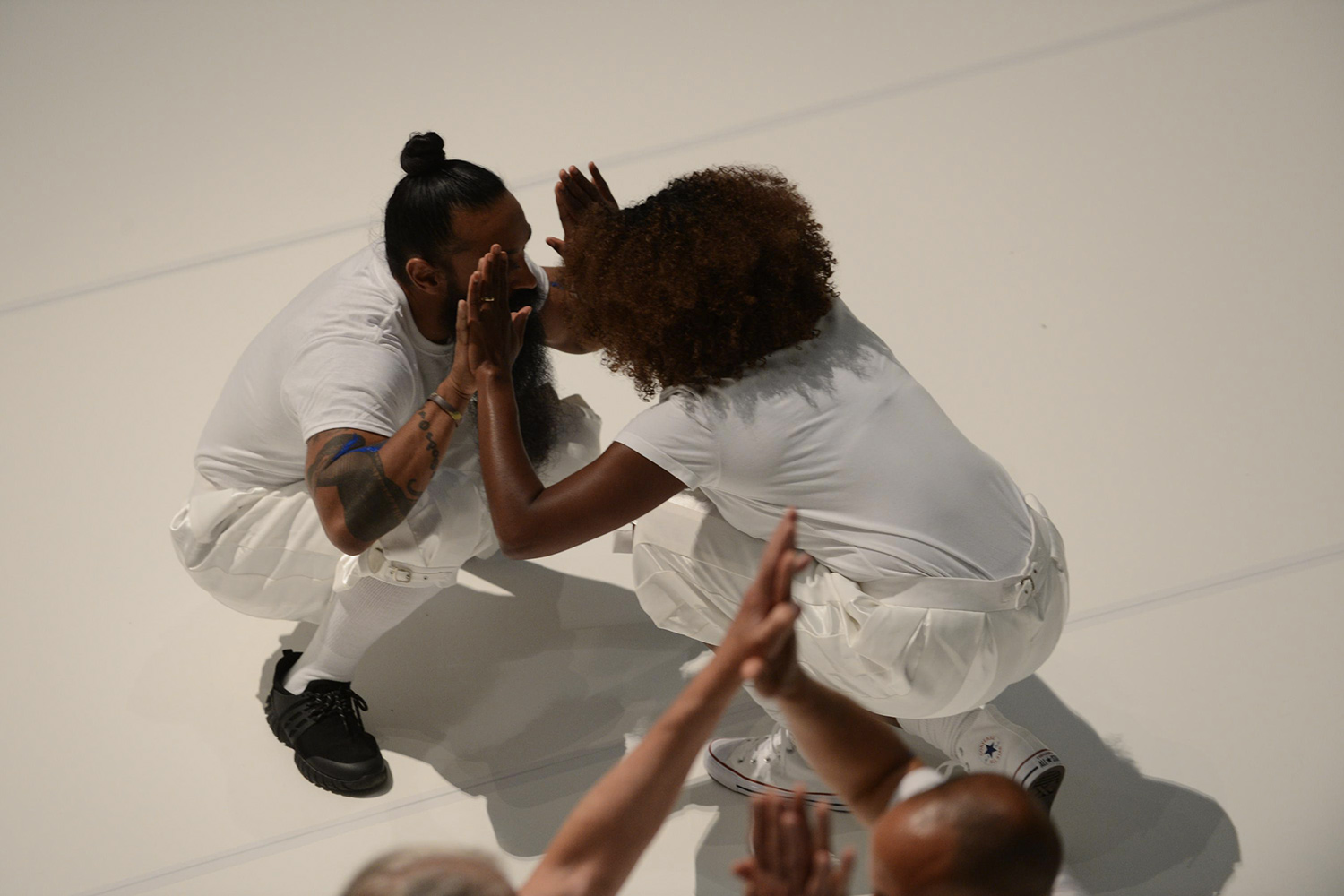

EJ: As a small nonprofit project space, at Cell we have been trying our best during this time to continue supporting artists as the forefront of our activity. Both “Queer Correspondence” and “Cellular,” an experimental live-art-and-media-based commissioning strand that we launched in June, were conceived with the participation of artists with whom we were already in working conversations with, and whose original projects were necessarily postponed due to restrictions brought forward by the pandemic. Many of the artists involved will therefore make a return in our 2021 exhibitions program, and these interim commissions have become invaluable in the way they have allowed us to continue a dialogue, a structure of support, and the building of trust during a difficult time. At the core of this forthcoming program is a desire to continue combatting an increasing feeling of social and political inhospitality towards marginalised communities in the UK, particularly in the context of the ongoing damage caused by the UK’s hostile environment policy and the triggering of Article 50 implementing Brexit, which also brought us Boris Johnson. Of course, this is an intersectional struggle, and the UK is not alone in the threat of fascism, so we’re working with artists near and far to think about strategies of collective resistance — to develop the tools and languages that I was referring to earlier and that are offered to us from queer, feminist, and immigrant traditions.

EM: The past year has been crucial to questioning social and political disadvantages, and the human body has acquired a new visibility, especially as a vehicle for manifestos linked to protests. What are your thoughts about the past year’s movements?

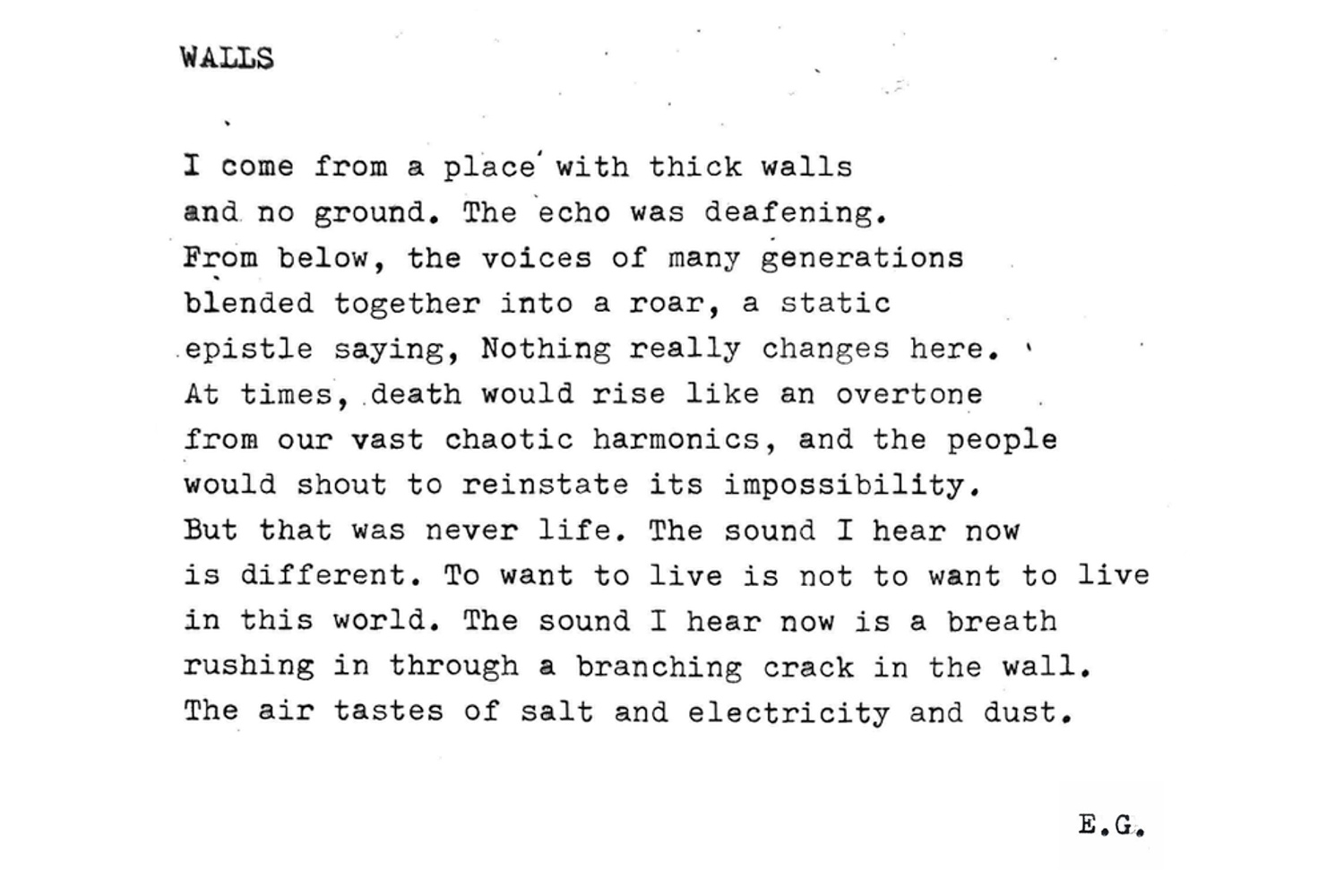

EJ: If we’re talking about structural change, Black Lives Matter as a movement I think holds a lot of potentiality on how to lead the path forward. The protests that took place in many cities across the world earlier this year importantly demanded a radical change; not a shift or reform, but a whole reimagining of what is possible — what should be possible — to be able to achieve justice and reparation. I think there is great power to be harnessed in calling for something to be broken. In one of the beautiful poems that Ezra Green wrote as part of his “Queer Correspondence” commission, he nods to making way for new possibilities — new worlds — through cracks in the wall. I believe we need to rip these cracks in the walls fully open so that, quoting Halberstam writing through the spirit of Audre Lorde, we create “fewer strategies of repair and more damage to the system; less fixing up and more taking down; fewer victims and more fighters.” I really hope that this new planetary pandemic can serve as a time to get acquainted with the experience and feeling of being strange, not so that we become desensitised or immune to it, but so that our strangeness can be channeled into a desire for change.