On a mild winter night I was sitting on a stoop outside of a club, in Milan, with a friend who had come to visit me from a foreign country. I was lamenting the anomalies of the city’s community of clubbers — perhaps in very vague terms, because my friend bounced back a rather straightforward question: “Does the city lack a scene or does it lack a space?” At the time I wasn’t able to answer — or let’s say that the drink I was holding fell on my shoes, or that I dropped my phone, or that my Grindr date showed up… But in the years that have followed that ruminative conversation, I’ve continuously posed the same question to myself, and continuously faced the reality of a vicious cycle in which deficient club spaces nurture a sophomoric clubbing culture and vice versa. Indeed, as throngs of aspiring art directors pile up in the city, clubs have been closed, opened, relocated, refurbished, rebranded, sold, bought and leased, all at the mercy of an entertainment industry that doesn’t seem too concerned with customer loyalty. Hence, if we are lost searching for where the party is, how can we gather and form a community? “Don’t you have Facebook?” one might legitimately ask in response. Touché. Whether old or new, in the city center or the hinterlands, fashionable or démodé, there are tons of clubs in Milan; and many boast quality sound systems, decent bartenders and reasonable covers. So, on a similarly mild winter night, this time sitting at my desk in solitude, I want to assume that Milan’s club community lacks that je ne sais quoi — read: the irrepressible drive for exploring new sonic scenarios, new dance-floor configurations, new dance moves, even new personifications of the “clubber” — that would make a space become inhabited by a scene.

On a mild winter night I was sitting on a stoop outside of a club, in Milan, with a friend who had come to visit me from a foreign country. I was lamenting the anomalies of the city’s community of clubbers — perhaps in very vague terms, because my friend bounced back a rather straightforward question: “Does the city lack a scene or does it lack a space?” At the time I wasn’t able to answer — or let’s say that the drink I was holding fell on my shoes, or that I dropped my phone, or that my Grindr date showed up… But in the years that have followed that ruminative conversation, I’ve continuously posed the same question to myself, and continuously faced the reality of a vicious cycle in which deficient club spaces nurture a sophomoric clubbing culture and vice versa. Indeed, as throngs of aspiring art directors pile up in the city, clubs have been closed, opened, relocated, refurbished, rebranded, sold, bought and leased, all at the mercy of an entertainment industry that doesn’t seem too concerned with customer loyalty. Hence, if we are lost searching for where the party is, how can we gather and form a community? “Don’t you have Facebook?” one might legitimately ask in response. Touché. Whether old or new, in the city center or the hinterlands, fashionable or démodé, there are tons of clubs in Milan; and many boast quality sound systems, decent bartenders and reasonable covers. So, on a similarly mild winter night, this time sitting at my desk in solitude, I want to assume that Milan’s club community lacks that je ne sais quoi — read: the irrepressible drive for exploring new sonic scenarios, new dance-floor configurations, new dance moves, even new personifications of the “clubber” — that would make a space become inhabited by a scene.

When I met with Jim C. Nedd, the founder of the club night Progresso, he recounted the beginnings of that experience, telling me that “people who came to the club felt awkward dancing to our music.” With a lists of invited guests comprising some of the most celebrated international DJs and producers of the “new” EDM — from Physical Therapy to Why Be, DJ Nigga Fox, Lotic, Jaws, Visionist and M.E.S.H. — and budding Italian artists like the Roman duo Vipra, Progresso endured only two seasons, from 2013 to 2015. Hosted first at Rocket, an indie rock club, and subsequently at Roxanne, a “disco Latino,” Progresso aimed to introduce the Milanese audience to a rough vocabulary of sounds that, according to the party’s name, would have “progressed” into a full-fledged music genre. (In this regard, it is telling that the lineups of the most recent editions of Club to Club, the paramount festival for electronic music held yearly in Turin, sport many of Progresso’s former guests.) Nedd ended the party because it wasn’t economically sustainable. Moreover, of Progresso’s few regulars, only a scattering seemed to truly embrace the project’s ethos; the majority was just going. “In Milan people are victims of the moment,” Nedd told me. Progresso was hyped for a second. And by the time that Nedd’s categorical rejection of the club industry’s logic (he never felt obliged to systematically promote his initiative, for example) had drowned the party into what from the outside could have been perceived as a carboneria of sound alchemists, its elitism equaled its breakdown.

That Progresso has always been about the music is evidenced by the most recent iteration of the project: the compilation Conspiración Progresso, released earlier this year on the American label Halcyon Veil, is a musical journey that summarizes Nedd’s vision. (Conspiración Progresso includes contributions by Bekelé Berhanu, Hvad, DJ Nigga Fox ft. Vipra, Zutzut and Draveng.) At the same time that the compilation’s limited edition of three hundred sold out on Boomkat, Progresso claimed its audience of music professionals and bode farewell to Milan’s partygoers. “Progresso cannot be a local product,” Nedd told me. “Because in Milan, the role of music is relegated to a nuance of the entertainment industry. I didn’t try to make people ‘enjoy’ my music agenda. And so they went for something more accessible. Who knows if they ended up having more fun?” Still, Milan’s experimental electronic music milieu is eminent, featuring producers such as Lorenzo Senni, whose first release for Warp is due this month, and labels like Hundebiss and Senni’s own Presto!?. Nedd himself is part of the music duo Primitive Art, together with producer and DJ Matteo Pit. (Primitive Art has shared stages with major-league artists such as Ben Frost, Oneohtrix Point Never and Arca.) These musicians and platforms are a constant in the city’s music lineups — and at events of every kind, too. Indeed, their inescapable, ongoing dialogue with the art and fashion industries often waters down their experimentalism and turns them into currencies of coolness, constantly eroding the earth where a local music scene might grow, and with it, an educated community of listeners.

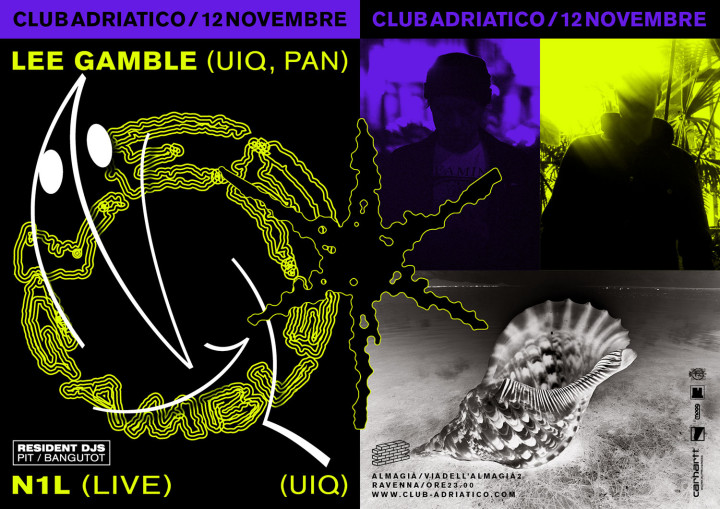

Via Primitive Art, Progresso found its prosperous doppelgänger in Club Adriatico, a monthly party established by Pit together with its clique, also in 2013, in their native Ravenna. Born and raised in the Riviera Romagnola, the land of the most celebrated clubbing scene in Italy, whose discotheques, like Cocoricò and Pascià, are signifiers for nightlife in the mind of every Italian, Club Adriatico has managed to re-infuse genuineness into a scenario that embodies all the neuroses of our society. “At the end of the 1990s the clubs of the Riviera got sick with a poisonous economic drive as they tried to imitate their Ibiza counterparts,” Pit told me. “The parties were injected with testosterone on steroids.” The consumerism of this scene spurred Pit to create a more intimate platform in which to reset the focus on music. “We always look at the history of the Riviera’s clubbing culture. But our main reference is the golden age of the late ’70s and early ’80s, when clubs like the Baia degli Angeli [today, Baia Imperiale, in Gabicce Mare (Pesaro-Urbino)] or the Melody Mecca [in Rimini, closed in 2000] were genuinely experimental.” With a steady roster of residents — along with Pit, it includes Florentine Herva, Milanese Still, and locals Hazina aka Petit Singe, El Putiferio, Bangutot and Nicolò — and guests of the caliber of DJ Richard, Actress, Errorsmith, DJ Stingray, Joey Anderson, Lee Gamble, Dopplereffekt, JD Twitch and Helena Hauff, just to name a few, Club Adriatico journeys through what Pit called “the different temperatures of new electronic club music.” “Our approach is based on curiosity,” he remarked. “We search for sounds that are still able to surprise us.” (A branch of Club Adriatico, the festival Loose, happens every spring in order to bring the party’s explorations even further into EDM-adjacent genres.)

Club Adriatico is hosted at Almagià, a multifunctional space located on the dock of Ravenna’s harbor. Heading to the party — which for me and my fellow Milanese implies either a train or a car ride of a couple of hours — feels like a pilgrimage, both literally and figuratively, into the history of Italian clubbing. First of all, it’s a trip to small-town Italy, the nondescript landscape that backdropped our childhoods. Returning here as clubbers, this nostalgic tableau gets dark: it brings to mind provincial nights from the ’90s, the hallucinatory wastelands of rave culture and the horrific images of the “stragi del sabato sera” [“Saturday night massacres,” the sensationalist name given by Italian news agencies when DUI accidents took the lives of twenty youths in a single weekend in 1989]. It’s also a trip to the Riviera Romagnola, where dancing places us within the high period of “Italian” nightlife. Finally, it’s a trip to a new club, both a space and a scene, a community that gathers on the dance floor for the music’s sake. “Club Adriatico is a social platform that never before existed in this area,” Pit told me — and it probably doesn’t exist elsewhere. Far away from Milan, from the creative industry and its discontents, this is the arcadia of clubbing.