“Reality changes; in order to represent it, modes of representation must also change. Nothing comes from nothing; the new comes from the old, but that is why it is new.” In 1938, when he penned these lines, Bertolt Brecht was living in exile in Denmark, spurred to a consideration of the “gap between the writer and the people” by cause of tragic political circumstances in Germany, and the necessity of producing “a faithful image of life” — a realism unbound by any set formal criteria or conventions.

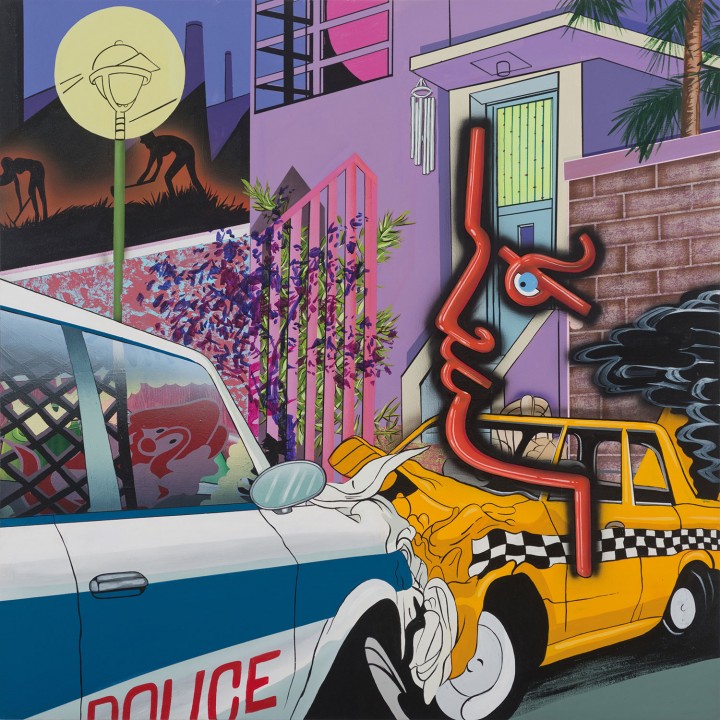

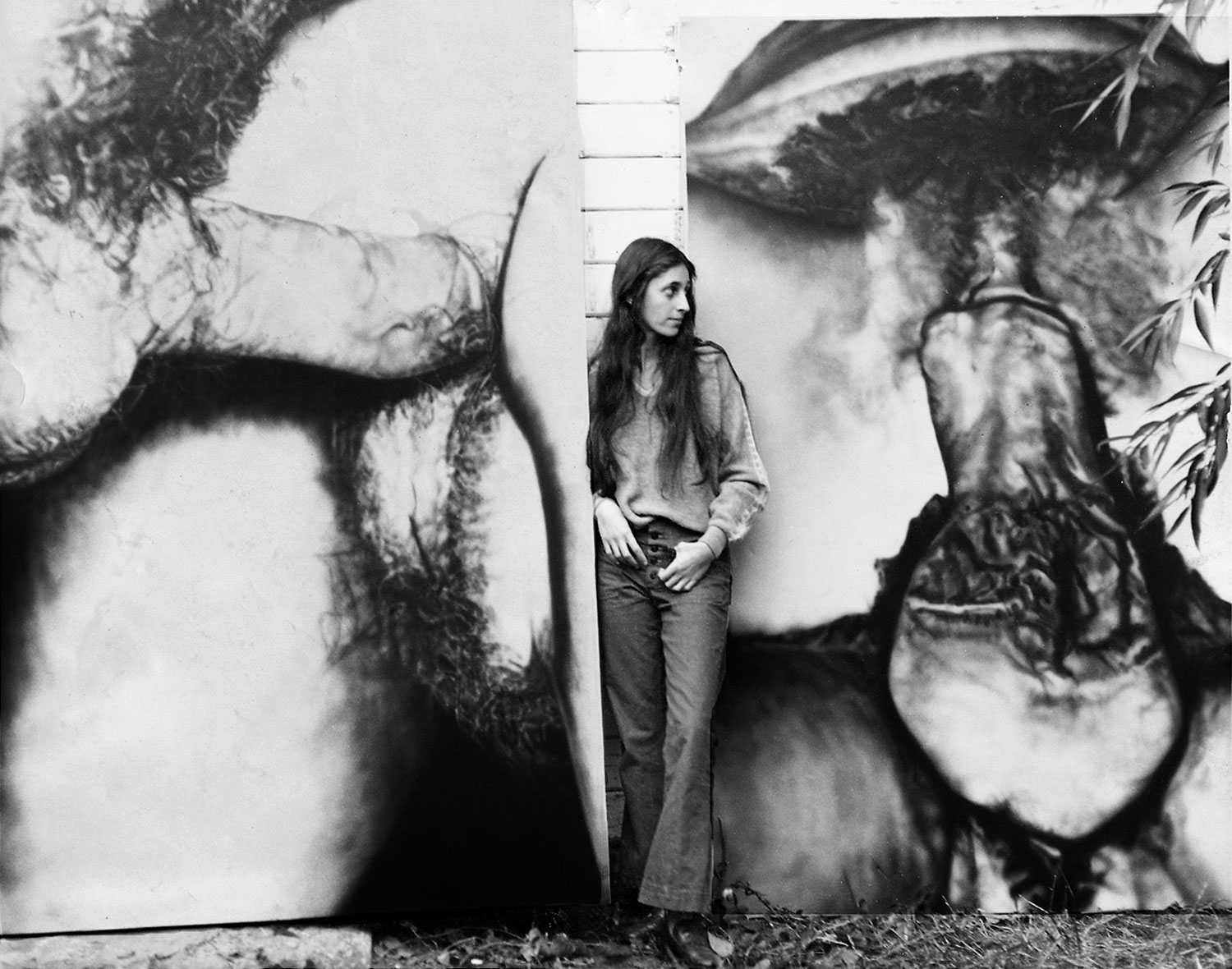

Under the profoundly different political and cultural conditions of an ever-prolonged era of neoliberalism and postmodernism, our “modes of representation” seem impossibly confused with “reality” itself. Three painters, distinct in terms of style and content, suggest in their work the augmentation of Brecht’s categories with a third: reality and modes of representation must necessarily triangulate with modes of consumption. Jamian Juliano-Villani (b. 1987, USA; lives in New York), Greg Parma Smith (b. 1983, USA; lives in New York) and Nolan Simon (b. 1980, USA; lives in New York) discuss with Eli Diner questions around taste, style, sources, banality and the real.

Eli Diner: I want to start with the question of sources. Each of you seems interested in a kind of excess of visual source material, which is, of course, a frequently remarked upon condition of both contemporary art and contemporary life. How do you position yourselves in relation to your sources?

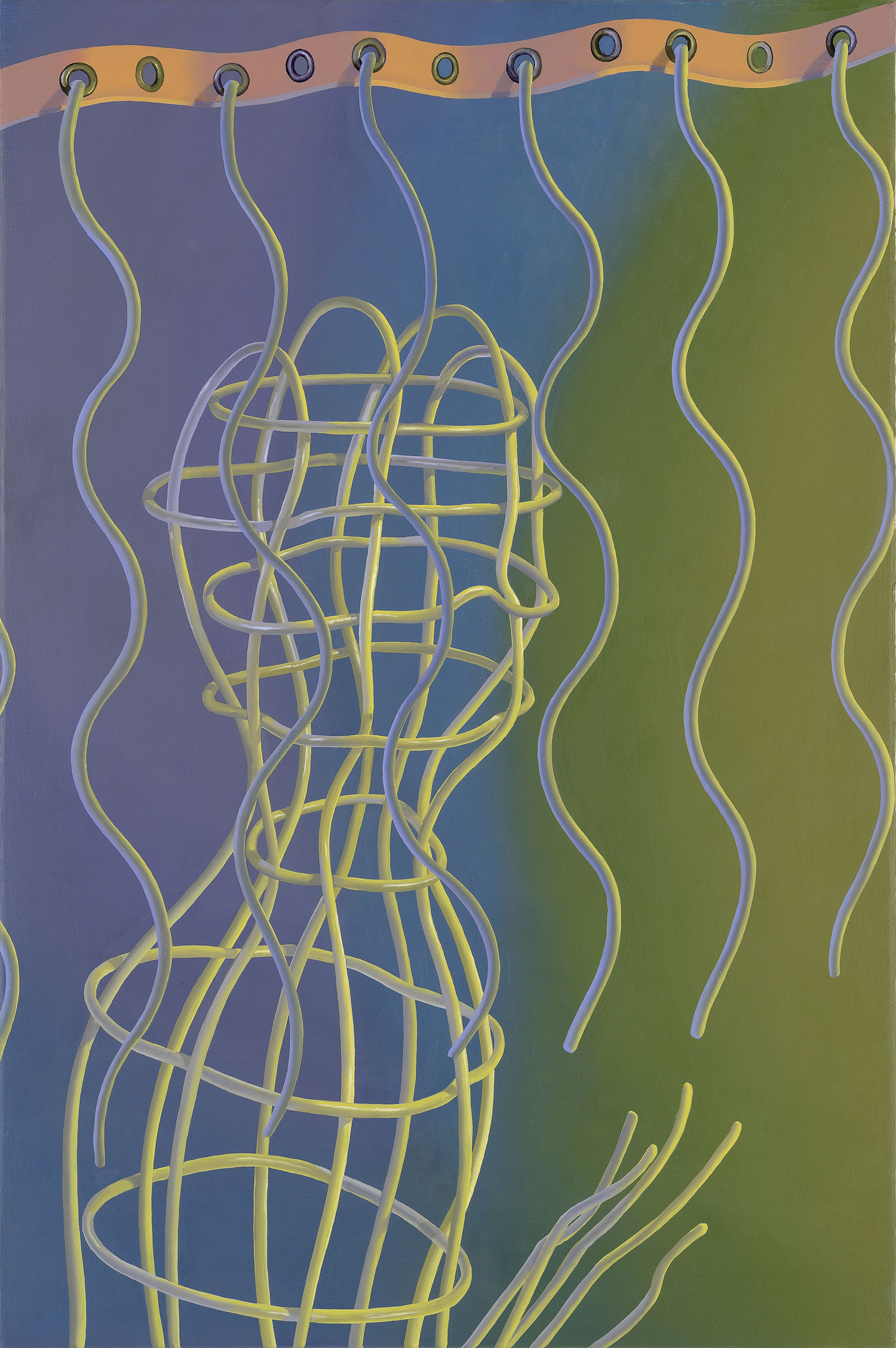

Greg Parma Smith: I use a few different established modes of painting in my work, and see them as allegorical — expressing a desire for some sort of cultural autonomy, whether that autonomy is really attained or not. Their specificity is important. I’ve been personally invested in these ways of making art, and my attitude towards them has taken on more dimensions over time. The ideological rhetoric of style is even more interesting to me than what is depicted in that style.

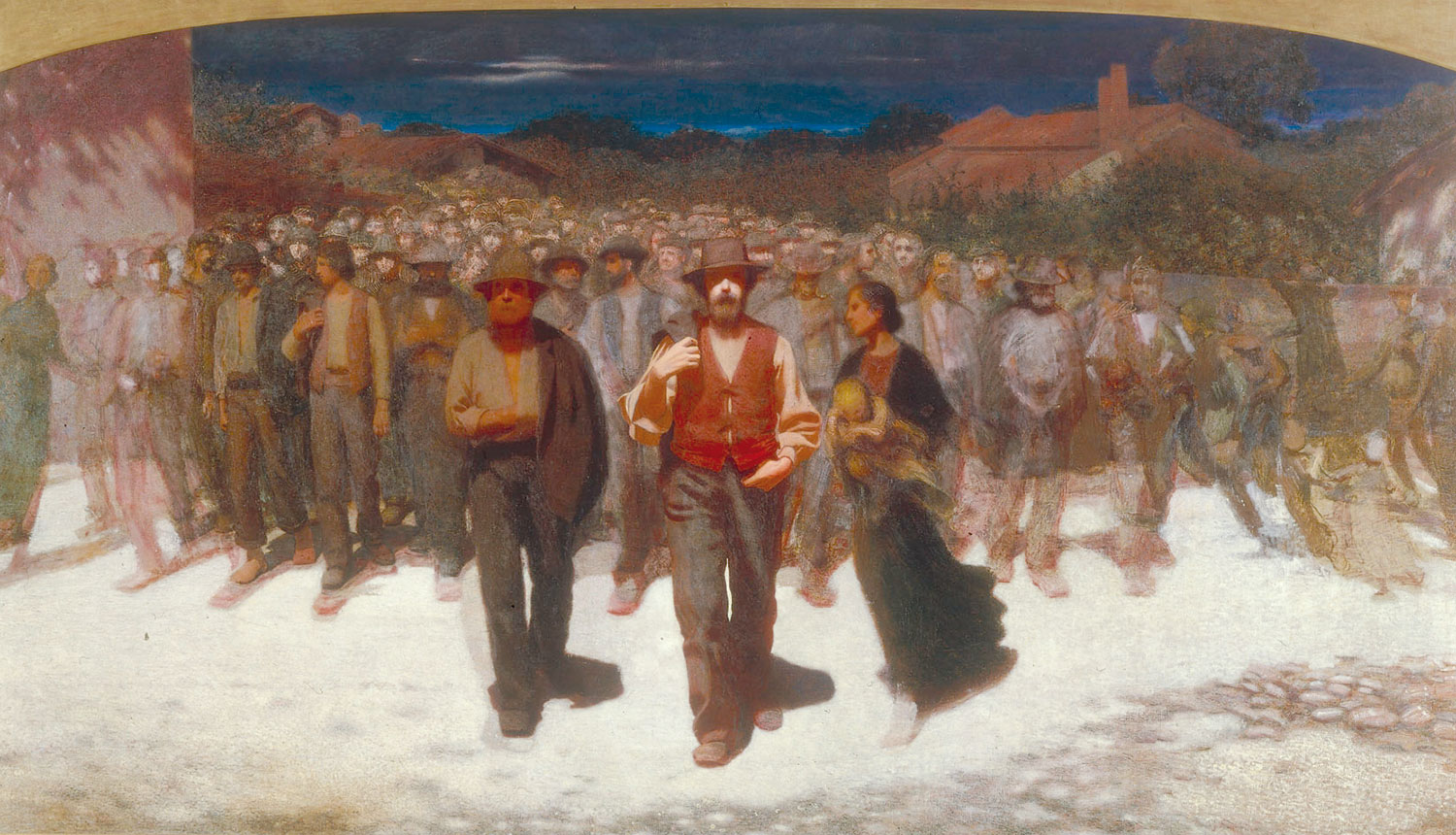

Nolan Simon: I try to maintain unstable relationships with my sources. The historical discourse of image fidelity is very productive for my work, and I allow myself to pull from and use liberally sources that in one way or another claim access to truth. I’m not much of a stylist. I’m much more interested in the gravity and grammar of images and questions surrounding the social roll of the painter.

Jamian Juliano-Villani: Excess is a relative term. My relationship to my source material is guileless. Some sources are heavily researched and ethically important to me, or just “favorites” that are staples in my paintings — like Mort Drucker, George Ault, Japanese Kappa, etc. I choose those things specifically for what I think is a subliminal cultural power; they are also time-specific but transcend the era in which they were produced. Others are more natural, less researched, impulsive. The latter I find while doing the hard research, things that just appeal to me. They come from almost everywhere — not just the cannon of painting tropes and styles, but also cultural symbols that aren’t self-congratulatory.

ED: Part and parcel with this excess is familiarity, which itself is, I think, a thread that runs through your work in various ways. Pushed further, you arrive at exhaustion and banality, and I wonder whether you see this as inescapable? Is it something to be interrogated, toyed with, celebrated?

JJV: I’m fine with exhaustion. Especially in regards to painting, or images in general. All the best shit has been done, and because we are so ego-driven and impatient, we always want what’s new, what’s next. But we tend to get ahead of ourselves and forget to look back for all the things we glazed over and potentially missed. That’s the beauty of the reference; it looks familiar but extremely alien, like a generic brand of cereal with a knock-off cartoon mascot. That off-brand identity keeps it away from being banal. And banality is the worst.

GPS: The tendency for capitalism/contemporary art to absorb cultural alterity is a concern I’ve felt compelled to deal with head on in my work, in the sense of working within obvious stylistic languages, and delineating them as such, separating and uniting space, but within the familiar medium of painting. Languages require familiarity, and speaking generally the banality of images is no worse than the banality of colors… that’s not at all to say the familiar is itself good or interesting.

NS: I have no real problem being obvious or boring. There’s more life in toying with images that feel somehow too understandable or overly familiar. More life in that than in dreaming, sometimes. Images are mortifying — they carry death with them and that makes dealing with familiar images risky. My paintings are content even if, or maybe because, they misunderstand the language of images.

ED: Nolan, there would seem to be a connection here between your interest in the overly familiar and your earlier stated interest in images that proffer a truth claim. I wonder if you could expand a bit on these. What is at stake (“risky” as you say) in these kinds of images? What does painting do to these claims of “access to truth” and familiarity?

NS: For Cezanne, the conviction that painting is capable of depicting fundamental truths regarding the nature of things was not up for question. Today, 109 years after Cezanne’s death, the world has dissolved, becoming fundamentally indistinguishable from the virtual world of networks, spectacle and commodity. So when Bruce Nauman made a sign saying “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths” (1967), we understand it to be tongue in cheek. Nauman is, of course, identifying the universal condition in which no artist authentically perceives him/her/themselves to be “true artists.”

The discourses of “truth” (and untruth) are inextricably bound up with discussions surrounding identity. Identities are fluid and constructed. But if truth is fluid, is it true at all? This state of things puts artists, and particularly painters, in an exciting and controversial new position. Painting is fundamentally intersubjective and its methods are artificial, but I see that as a productive contradiction — ironically placing us in a uniquely relevant position. How do we develop a politics-of-images suited to this new individual and fluid reality? How do we approach imagining (and imaging) “truth” as a problem? These questions should be directed at particularly ambitious, masochistic painters. For a while it seemed that art had reacted to this task by relegating itself to its own construction. The materials, gestures and history of art became the only justified subject of painting. This is why I said painting images is risky. It’s still the case often enough that painting doesn’t believe itself to be capable of talking about anything but itself.

ED: This opens on to the question of taste, which can be a thorny one. We are supposed to be living in a lawless aesthetic regime, where anything goes and where problems of taste have been rendered moot. And yet seemingly they persist. How does taste — bad or otherwise — operate in your work?

NS: Taste and sensibility are certainly interesting to me, but I spend more time looking at the ways images reproduce themselves and help lubricate parallel worlds. As an example, memes seem to have some primordial drive to them which transcends taste. Cats and foodporn aren’t coke bottles and soup cans, and the differences, I think, are crucial.

GPS: The currency of taste is as potent as it’s ever been. It fortifies distinctions of identity and class. I want to go straight up through the middle and out the other side — taste is at the crux of my interests.

ED: Greg: I’d like to follow up on this a bit (and return to your earlier comment on the “ideological rhetoric of style”). Could you elaborate on how you think this regime of taste operates and how your work seeks to short circuit or critique it? And given your interest in the politics of taste, do you think that any investigation into the “currency of taste” necessarily reproduces it?

GPS: The intense power/fluidity of taste as a social medium and currency encroaches on all painting. Naturally one wants to push back and keep some space open for oneself.

I think the desire to somehow abstain from the illusory opposition of good and bad taste relates to the topic of realism — it’s an ethic of objectivity. Maybe it’s even a little puritanical — I’m a New Englander after all! In my painting, that attempt at a neutral space is important because the content also relates to taste. The art styles I’m representing in my work (like realist painting, zines, comics, graffiti, the orientalist exotic) themselves have to do with trying to negate trappings like taste and Western art history and recover some natural human autonomy, to the extent that’s possible. I don’t think this purity can be attained in a universal or lasting way, but the double bind of that striving might be depicted. Representation is ultimately a negation. It’s difficult to explain but in the right artistic space, for me, that negation symbolizes cosmic freedom.

JJV: Taste is a very real construct. It’s incredibly hard to make something without thinking of your own taste. I always joke there’s no way in hell I’d ever hang my own painting in my house; its important for me to not even think about that when I work — I’m with Greg on this one. It’s classist and it dictates how, and more importantly, who, can engage with your work. Pretense goes hand in hand with taste. I refer to this Zappa quote: “If you want to get laid, go to college. If you want an education, go to the library.” It doesn’t matter how you get there, as long as you get there. Whatever works.

ED: All three of you — in very different ways — employ painterly techniques that could be described (with whatever qualifications and complications) as, on some level, realist, or borrowing techniques from the tradition of realism. I don’t know if the term itself has any significance for you. But the question of the relationship to real I think grows naturally and intrinsically out of the question of sources. That is, at a very fundamental level, the question of what to paint can seem like an analogue to the more universal question of what to Google. How do you negotiate, on the one hand, painting, with its often-burdensome history and vast repertoire of techniques and styles, and on the other hand, this novel experience of reality? Put otherwise: how does painting mediate this novel reality, or how does this experience of reality mediate painting?

JJV: I am not a classically trained painter. I’m largely self-taught with those awful acrylic 101 books, YouTube tutorials and trial and error. I aggressively teach myself how to improve my painting skills. My attempts at realism usually get lost in translation, which is fine. And I just try to paint it in the most efficient way I can. For me, the airbrush is an allegory for the meeting of technique, illusion and the representation of the tangible world. I get to make the decision if the thing I’m painting looks accurate or surreal, and if it even matters.

GPS: As many art historians have shown, Realism has always been conditioned by technology, so a realist practice in our moment wouldn’t necessarily resemble Thomas Eakins, but along the lines of your question, of course it also could. In my work I rarely use image searches or photographs in a direct way — but any multifaceted stylistic approach probably reflects the simultaneity and entropic liberalism of the internet. For me, the history of painting and its technological obsolescence is exactly what enables it to sanction a space for aesthetic issues to be contested.

NS: Realism started for me around my first trip to the Barnes Foundation. I had already moved from Detroit to New York and worked, for all intents and purposes, as a painter for a few years. I went there with three artist friends. At the time I was curious about primitivism as an antecedent to the punk/DIY culture I’d grown up with. At the Barnes I believe I found the punk ethic stretching back even further, into early Impressionism. Whether that ethic was really there or not seemed unimportant to me. Feeling like it was there, even as an anachronism, helped create a loop, like a wormhole, connecting artists like Paul Thek and Lee Lozano to painters like Manet and Renoir. Greg and I are on the same page about the space opened up by painting’s technical obsolescence. The deep time painting carries with it is what makes it useful to us.

I follow an Instagram account called @renoir–sucks–at–painting and he just posted an exchange where Manet and Monet are painting together. Renoir waltzes in, asks to borrow paint, canvas and brushes and dashes off a portrait. Manet says to Monet, “That boy has no talent as a painter. He’s your friend, you really should tell him to give up.” I identify with all three of them.