At a few minutes past 1:00 AM I enter the dark cave of MusicBox, a club under the bridge in Cais do Sodré. The tourist boom has been a scourge to this area of Lisbon — an uncontrollable rhizome of bleak Airbnb rentals obscuring dodgy deals brought by foreign investors to this corner of Europe. But just as the neoliberal reach spreads its pervasive tentacles through the more inhospitable corners of the city, converting red-light districts into newly branded bourgeois hotspots, movements of resistance exist. Beats proliferate through the underground catacombs of nocturnal Lisbon, invading lesser-known places and radios passed by, erupting in tunnel clubs. DJ Nigga Fox is about to play. The crowd dances frantically in a mesh of twerking bodies, whose tidal movements envelope anyone passing by. In the deep cave of the venue, class tensions are extinguished through bodily spasms. Tribal movements propagate in circles with a viral, guttural speed propelled by the DJ. A cataract of sweat purged from bodies melds distinct individuals into a pounding muscular mass.

At a few minutes past 1:00 AM I enter the dark cave of MusicBox, a club under the bridge in Cais do Sodré. The tourist boom has been a scourge to this area of Lisbon — an uncontrollable rhizome of bleak Airbnb rentals obscuring dodgy deals brought by foreign investors to this corner of Europe. But just as the neoliberal reach spreads its pervasive tentacles through the more inhospitable corners of the city, converting red-light districts into newly branded bourgeois hotspots, movements of resistance exist. Beats proliferate through the underground catacombs of nocturnal Lisbon, invading lesser-known places and radios passed by, erupting in tunnel clubs. DJ Nigga Fox is about to play. The crowd dances frantically in a mesh of twerking bodies, whose tidal movements envelope anyone passing by. In the deep cave of the venue, class tensions are extinguished through bodily spasms. Tribal movements propagate in circles with a viral, guttural speed propelled by the DJ. A cataract of sweat purged from bodies melds distinct individuals into a pounding muscular mass.

The corners of the dance floor are populated by observers who enter the circle when the DJ representing their crew is the next to play. Heavily stoned, drifty eyes are drawn to the provocative hips of dancers who enthrall us with their striking moves. The circular tension of the night rises across the steady tempo of erupting beats. Clubbers come and go as the crowd grows dense on the dance floor.

Príncipe nights have been occurring monthly for more than four years in this club in the center of Lisbon’s downtown night scene. Organized by Príncipe label co-runners Nelson Gomes, José Moura, Márcio Matos and André Ferreira, the party helped to launch producer Marfox’s first epic record, Eu Sei Quem Sou, in 2011, and introduced to the world a whole dynasty of Kuduro music producers who have become known as “the Foxes.” The rhythms of Kuduro, originally from Angola, include sharp bassy beats and up-tempo tribal melodies occasionally syncopated by creole-pop incursions and distorted hornlike sounds. This guttural collage is intrinsic to the DNA of the Foxes’ cultural roots and therefore is mostly nontransferable, as its code can only be divined by our blood’s pounding circulation. Over the years, Príncipe has developed a catalogue of over a dozen releases by Kuduristas based in Lisbon suburbs (Bairro da Quinta do Mocho, Pendão, Ameixoeira, among others). But they have also scouted producers of the genre within communities of Portuguese-immigrant descendants from other cities, such as Bordeaux, home of the prodigious Nidia Minaj, one of the most recent additions to Príncipe’s roster.

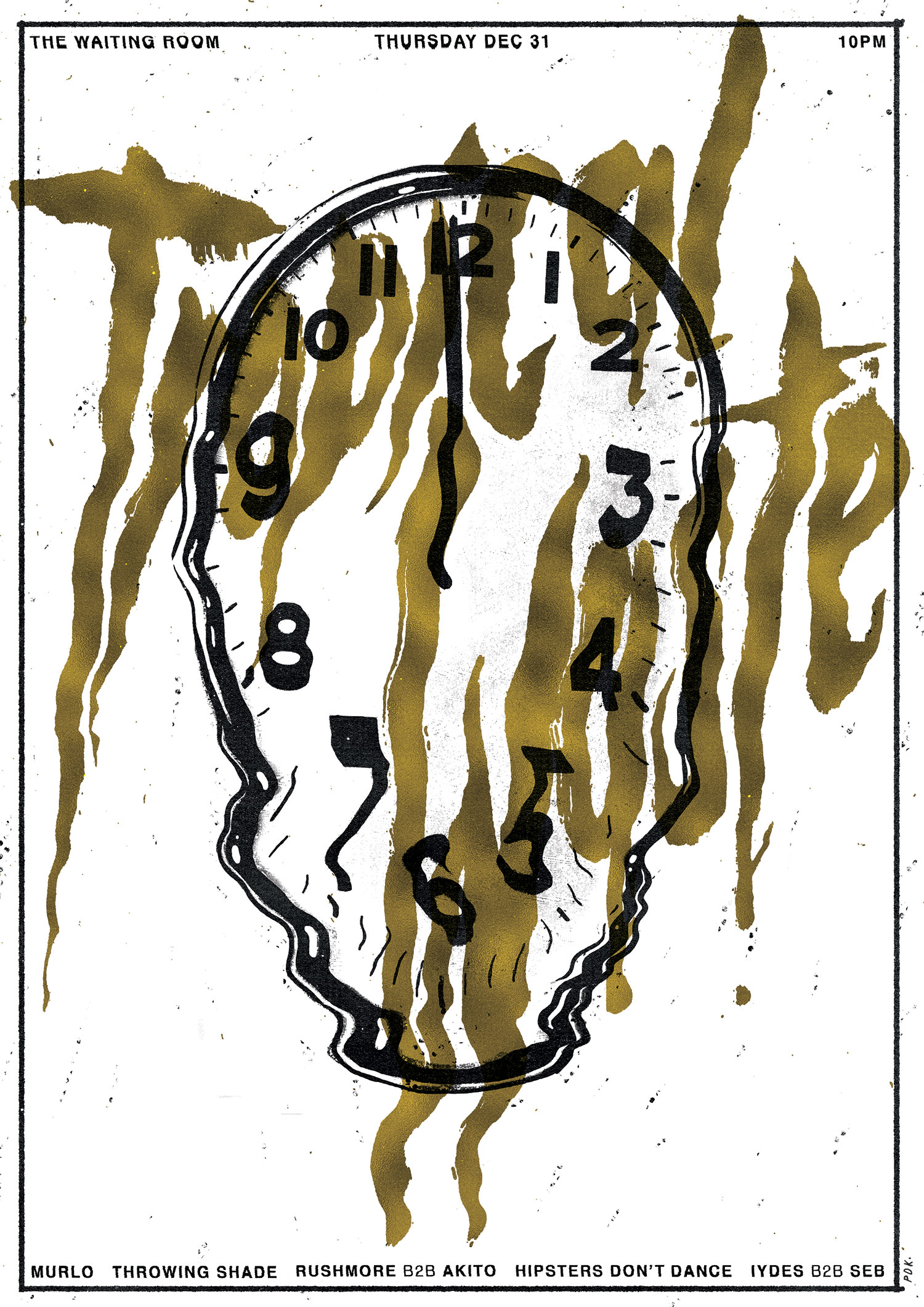

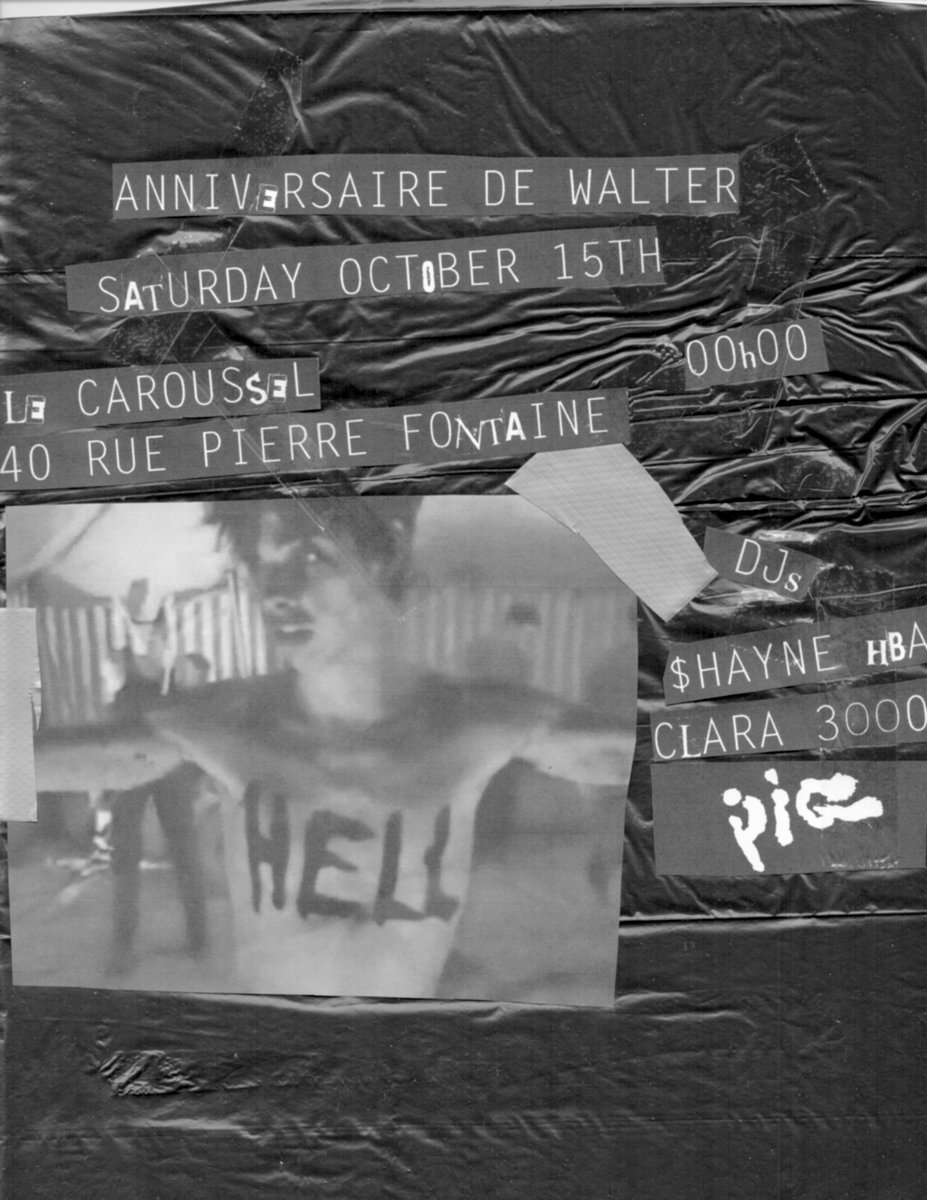

Príncipe’s visual identity has also become iconic, refreshing the graphics of music promotion in Portugal by erasing the stiffness of the ’00s Photoshop era and the serious face of the business. Its posters are mostly black-and-white with a penchant for DIY expressed through minimal collages of found images. With a stencil-like quality, the graphics of Príncipe are recognizable at a distance not only for the quirky names of most DJs, but also for the bleakly charismatic humor that its crude collages evoke.

Príncipe nights have established “the ghetto sound of Lisbon” and revived the city’s nightlife, becoming a place of pilgrimage for fans of electronica while attracting a series of foreign producers, promoters, critics and clubbers. As one of the first independently run club nights since the peak of the crisis, these nights are the first port of call for new works by local Kuduro producers, many of whom rarely play elsewhere. Straight from their bedroom studios, Príncipe producers strike dance floors with their punchy, acidic beats. Thriving through the gloomy penniless nights of the economic crisis, and simultaneously burying techno for good, these works call attention to undervalued surrounding rhythms.

Kuduro beats moved beyond the ghetto years ago. Although heard on the pirate CDs of Helder Rei do Kuduro, or just in passing traffic, they’d never been fully explored by the broader clubbing community. West African music infiltrated the Lisbon scene quite some time ago, sprouting initially from small venues and improv nights, at the same time that Buraka Som Sistema were gaining wide international recognition. But it was Príncipe that played a major role by musically intertwining long-emigrated African communities in a Portugal still wounded by the legacy of its colonial past. Its parties reversed the ghettoization of music. Its thumping dance floor has become a platform for the communion of clubbers, promoters, and artists, and a firm fixture on the calendar. The best bass night in town has now become a monthly ritual of bodily catharsis and new forms of performativity.

The phenomenon is spreading. In September of last year, Festival Zona Não Vigiada (Unsupervised Area Festival) was organized by Príncipe in Zona J, a social housing block located in the Chelas neighborhood of East Lisbon, popularized by the eponymous 1998 film in which drug dealing drives social exclusion. Chelas was unfamiliar to me until an afternoon when Príncipe gathered Newham Generals, Pega Monstro, DJ Firmeza and other musicians at a local open-air basketball court. It was an afternoon of pure musical bliss in which the generations merged freely, not a cop in sight.

Príncipe nights are run by a core group of friends and musicians. Some of them are members of the promotional agency Filho Único, which has, since 2007, organized the best music events in town, starting with the mythical Galeria Zé dos Bois in the early ’00s, and fomented a new generation of musicians, one that has only increased exponentially over the course of the crisis. The well-nurtured Lisbon scene owes much to this group, who has invested heavily in turning the city into a ideal destination for bands and travelers in search of new sounds. As a consequence, Príncipe’s music has begun to invade the international club scene — in London, Mexico City, Los Angeles and elsewhere. These days it weaves its way through contemporary music via members of labels such as Fade to Mind and NAAFI, and broadcasts by NTS Radio and Berlin Community Radio. No wonder.