Precious Okoyomon breathes new life into their installation topographies with the solo exhibition “the sun eats her children” at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis in Rome. I spoke to Okoyomon about this show before the opening, and what came to mind was the image of their often chasmic spaces filled with butterflies living among kudzu vines, sugar cane, cascading water streams, and greenery teeming with poisonous wild flowers. Okoyomon once again brings viewers into a serene and momentary world, this time layered with a foreboding soundscape designed by Kelsey Lu, and inhabited by a half-awake animatronic bear. Once removed from the space, an onerous realization arises, and we are left with a sort of apprehension — typically associated with catastrophic destruction. However, Okoyomon observes this certitude and its ruinous backdrop with keen possibility. Okoyomon’s work is situated in all that survives at the periphery of the apocalypse — a present circumstance for those subjected to an ever-occurring apocalypse. “The already apocalypse,” the artist tells me, refers to an integral component in their work that is emerging from Saidiya Hartman’s writings on grief, collective mourning, and Blackness as a site of ruin and resurrection in the US; Christina Sharpe’s notions of weathering the anti-Black singularity of the present; and Etel Adnan’s book-length poem Arab Apocalypse, written just before the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War. Okoyomon invited Hartman to Rome to rehearse a staging of her essays “The End of White Supremacy: An American Romance” and “Litany for Grieving Sisters” in the ancient port city of Ostia. Hartman worked the texts into a performance with Okoyomon and collaborators Tina Campt, Charlotte Brathwaite, Okwui Okpokwasili, Arthur Jafa, André Holland, Imani Azuri, and Esperanza Spalding. Sitting among the Roman colonia ruins of Ostia, we watched Hartman’s words on “love in a world where Black life is all but impossible”1 engross performer Okpokwasili in total devastation, with every line more destabilizing than its antecedent. Alluding to the canonical understanding of “apocalypse,” derived from its Greek origin meaning to uncover or reveal, Okoyomon’s trajectory feels revelatory amid the culmination of theoretical threads that interrogate endings, afterlives, and becomings. An ongoing and multifarious pollinating effect occurs through every encounter with Okoyomon’s work, and what gradually develops is a willingness to just let things take their course “in all kinds of weather [that is] the totality of our environments; the weather is the total climate; and that climate is anti-Black,” as Sharpe writes in In the Wake. While the nonhuman species inhabiting these spaces become subject to growth, death, decay, and burning, we are instilled with a pervasive, revelatory mood. Okoyomon eventually expresses to us how we are either afflicted, implicated, or simply the residual seeds of this apocalyptic weather.

Jazmina Figueroa: Can you tell me about the work you are developing in Rome at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis and whether it explores similar themes as your 2022 installation To See the Earth Before the End of the World in “The Milk of Dreams” exhibition at last year’s Venice Biennale?

Precious Okoyomon: It’s somewhat the same, in the way that I like to work with natural materials, but also very different. Maybe one will see the immediate similarities, extensions, and pieces of that previous work brought into this new space. Similarities like, there will be butterflies present for the show in Rome and butterflies are a common motif for me. I’m actually bringing in a specialty breed of butterflies for this new work. This species is really hard to find and I’m working with a very specialized butterfly breeder who is willing to do this for me, which I find so beautiful.

JF: What is the butterfly species called?

PO: The butterflies that were in the work in “The Milk of Dreams” exhibition are called black swallowtails. Now, for the upcoming show in Rome, I’m breeding butterflies called purple emperors and blue morpho that feed on rotting flesh and sweat. The idea is that when you come into the show, the butterflies are going to lay upon you and lick your sweat off of your body. These species are known to have disgusting feeding habits; they love to feed on animal corpses, mud puddles, and human sweat. They are sort of like bottom feeders — or carnivores. And at the same time,

they’re so beautiful to look at and they’re like, “Oh, we love flesh.”

JF: I saw the Venice work at a later stage, around September, and at that time everything had been enveloped by a wild landscape, super green and lush. I missed these aspects of that work, and hearing you speak about it, I’m realizing that there’s so much that guides the work.

PO: Yeah, most people just enter the space and don’t see it or get it as a full environment. Sant’Andrea de Scaphis is a really beautiful space because it’s a tiny chapel. The show is called “the sun eats her children,” and it’s in the smallest space I’ve ever worked in. At that size, the work feels more vulnerable and there’s something comforting about that. I want you to feel held in the space. I will be planting a field of poisonous wildflowers there, and there will be purple emperor butterflies flying everywhere in the room. The floor for this work is made up of black volcanic ash, and in the middle of the room is a child-size bear. I’m making a bear, like the one I made in Japan [for the Okayama Art Summit, titled Touching My Lil Tail Till the Sun Notices Me, 2022], but she’s going to be animatronic with a big white bow and wearing her white underwear. She’s going to blink and breathe, and then she’s gonna scream because she’s witnessing the end of the world as she wakes in and out of this dream state.

JF: You often talk about not anticipating the work’s evolution and afterlife. Do you see “the sun eats her children” as the afterlife of something else?

PO: Everything is always inspired by poems. The Venice work was inspired by Ed Roberson’s beautiful book [To See the Earth Before the End of the World, 2010]. And this show is inspired by poems and writings of a few of my favs, like Etel Adnan and Christina Sharpe. I am thinking with and through The Arab Apocalypse and Ordinary Notes, and the always already apocalypse at the end of the world, how we sit through that, and how we rebuild. What is that solar pulse?2 I see myself as being in a world and lineage of “the always already.” As in, what comes after is where I maintain my space and where I’ll always be situated. A space of post-futurity. We’re in it, and the world is always ending for somebody. I always say the end of the world happens once a day for someone — who is usually Black or brown. I’m giving space to those different and ever-present apocalypses. How do you hold it? How do you sit inside of it? How to initiate these spaces of intense vulnerability? When you are in this kind of apocalyptic space, I wanna hold you. The bear has this rising scream that takes over this apocalyptic space. It becomes a solar swallow engulfing her into the intense cosmic e”uvia of the world. She seems to spit all of that out and then re-engorge it.

JF: Can you talk more about this bear’s characteristics, its animatronic qualities, and especially the scream. Is it something machinegenerated or is it coming from a voice?

PO: I’m going to be working with my friend Kelsey Lu, who is an amazing musician. The scream is a vocal recording using a mixture of myself, Saidiya Hartman, and Okwui Okpokwasili screaming together. I think it’s nice; the bear makes this beautiful solar swallow using the voices of Black women. Yeah, it’s quite formidable, our rising scream together, that ends in somewhat of a chaotic laughter. I feel like that’s like the dark-cosmic-e”uvia, dark-energy-of-the earth sound I’m talking about — Black women screaming.

JF: That’s great how you say that with a smile. This, I feel, characterizes your approach to certain dichotomies that you seem to cherish. For example, your affinity toward the kudzu, with its invasive characteristics, and your invitation to flesh-eating butterflies. You maintain this expansive thinking of how material, embodied, and natural ecologies are intertwined. Do you think this appreciation expresses something more subversive, perhaps a resistance?

PO: It’s the constant resistance for me, especially in my desire for this real investigation into the natural world. If you look at kudzu, it was supposed to be a miracle plant for the US. It was brought over from Japan after slavery [was abolished] and was going to magically fix everything. Then it became this monster that ate the South because people didn’t know how to work with kudzu. You can’t just bring a magical seed from Japan and expect that it is going to magically fix the topsoil after sixty-plus years of slavery that was deteriorating the soil by over-planting cotton. Kudzu does this thing of showing how Black life is perpetrated in the US. A magical plant doesn’t fix anything. You know what it does? The kudzu roots itself so deeply into the ground that if you were to dare to take it away, the ground would literally crumble in the South. It’s holding the foundations of the soil together, which is so fascinating to me. And honestly, so beautiful, as it depicts its magical qualities differently than expected. How can you be the monster but yet be the same thing holding everything together? Is that not an exacting depiction of the Black libidinal economy? I’ve had so many funny things occur in my love relationship with kudzu. I had a garden in Aspen for two years where I was like: I’m growing kudzu and nobody is gonna find out. Of course, it’s Aspen, and whoever sees a strand of kudzu begins writing letters to the city.

JF: This plant is policed.

PO: Yes, environmental racism is real, and that’s what I’m trying to show people in this constant work with the natural world. The natural world does a really good job of depicting things we don’t like seeing so clearly.

JF: Perhaps as a mirror? I mention this to refer to a word you often use to describe your larger-scale installations — the “portal” that one enters. What transformations or mirroring is occurring at the threshold of your installations? Why is the portal important to you?

PO: I’m just trying to create actual space-time. How do you make space-time shift and change? By allowing people to fragilize, allowing people to soften inside the space, which is very hard to do. Unless you change every sense: smell, sound, light, and give them a miracle. [laughs] You have to abduct people and take them into a temporal space: those are my portals. How do I arrest every sense. you have? How do I give you peace? And also frighten you enough to remember some type of umbilical pulsation and connection to the Earth? My key spaces, questions, and threads in the work are to give you something that you remember that you had but don’t know how to get to anymore. Venice, for example, was really specific because you walked through the whole exhibition, you were exhausted, and then you got to this room. There’s a feeling of being unsure of what you’re walking into, and you’re maybe thinking: Is this an emergency or a blessing? That’s where I’m trying to always locate people, between an emergency and a blessing. I’m finding a present breath. If the portal can do that, and allow a little bit of fragilization, then I have accomplished something. I have provided a different way of thinking, allowing yourself to breathe into a new form of thinking, rest, fragilization, or at a different pace like slowing down. I don’t control anything in the spaces I plant. I plant the seeds for the portal and allow it to do its thing, to make a miracle of its own. Then I invite people in to find themselves or find whatever blessing may be in there for them. I can only plant the seeds.

JF: Well, that’s another thing that I have come to understand about your work, that it has a lot to do with permission or a deliberate act of witnessing — witnessing things as they grow if they’re given the time to develop and transpire.

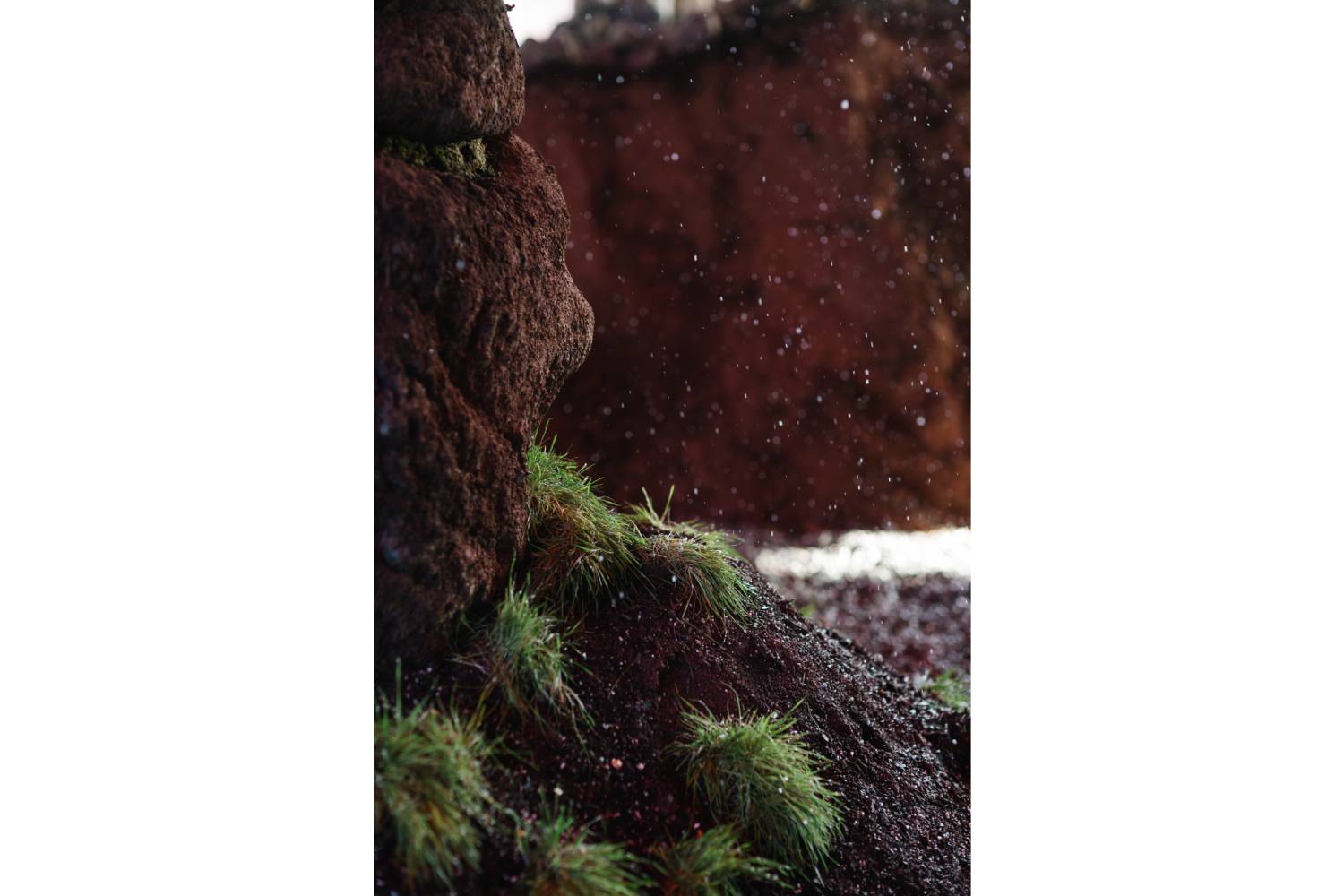

PO: For me it is all about witnessing, co-witnessing, and the compassion that comes from being in a space with other people, or sometimes by yourself. In March 2020, after the COVID lockdown, the work [titled Fragmented Body Perceptions as Higher Vibration Frequencies to God] at Performance Space in New York is where I burned all the kudzu ash from my “Earthseed” exhibition at MMK, Frankfurt. As a result of the burning, the ash rained down, creating a kind of soft bubble rain, and the space was opened some hours later so people could visit during the evenings. It was interesting to see who would go. Because of the burning ash you could say, “This is the space of mourning,” while other people were thinking, “I’m having my kid’s birthday party in here.” When you make space and allow people to use it in any way they want, it is interesting to see what they do with it. Once I went into the space and somebody was having a date, so I was tip-toeing around them, and sometimes there would only be one person in the room.

JF: What has brought you to this point of creating such spaces?

PO: I think all of it has been enmeshed together. I’m really lucky that deep, deep within me I carry the universal love of this world. I’m very grounded by love as the energy that flows and moves everything in the world. I think that love organically shapes me, and I want everyone to witness that in any way possible: to witness the connection, witness the love and the energy that flows in between everyone. But then the world is always ending. So, the only beginning is at the end of the world. I love Saidiya Hartman. I love Fanon. I love Bracha Ettinger. These are like my matrixial, many mothers. They’ve shaped me to have an actual praxis of unending love and energy work, which is making these portals. It leaks out into my practices of cooking for people in this very vulnerable and explicit way. It’s the way I communicate with people every day; it is an endless rapture for me. Which then, like, falls into the work. I can’t separate anything, which is also quite terrible for me. [laughs]

JF: Can you speak on the embedded historical and life cycles of other plant species brought into this work and other installations?

PO: It’s a mixture of this chaotic blessing. I’m always learning, growing, and expanding in this way that overreaches constant visions of excess and abundance. My visions of excess are a bit of a blessing and chaotic!

JF: I agree, that is a blessing.

PO: I want everything, always, all the time. For me, it’s a correspondence with deep fragilization and constant witnessing for everybody. I’m always saying that I’m endlessly talking to God, this is my poetry. Because everything starts with the poem, and it always has. I happen to be an artist who has the heart of a poet, and this influences everything I do. It’s a nonstop poem — the relation between everyone that I work with and the projects I do functions as this poem. The Venice work, like older works, was burnt and will be part of another show. Everything leaks into everything else. It is endlessly leaking; this is what I constantly show people. It’s love leaking and the entangled, abundant, and excessive syntax of that.

JF: What is the act of burning for you then? When do you decide to start something new through burning, and how does that play into how you think about the work?

PO: When you work with an invasive plant, you can’t replant it. And how do I understand the dust of that? The dust is so important; I want to be engulfed inside the dust of memory. I think a lot about Christina Sharpe’s weather theory where anti-Blackness is the weather. How do you live inside of that? Every time I burn the kudzu, every time I disintegrate that material I say, “This is the weather.” The work at Performance Space was a moment of asking how do you deal with all of this death that’s happened? How do you hold it? You could feel it in the air, feel the thickness of how the air has changed. And then, I’m like, “Oh, thank you, celestial comrade. Thank you, God, I received this ash. I received the burning.” I receive all of it and put it back and the dust swarms in the air and you breathe it and it changes you. There are so many different forms of transformation. It’s about how to accept all of it and how to hold it. How do I hold this? There are many different forms of the work, it can live on in so many ways. I’m always pollinating. It’s just more pollinating.