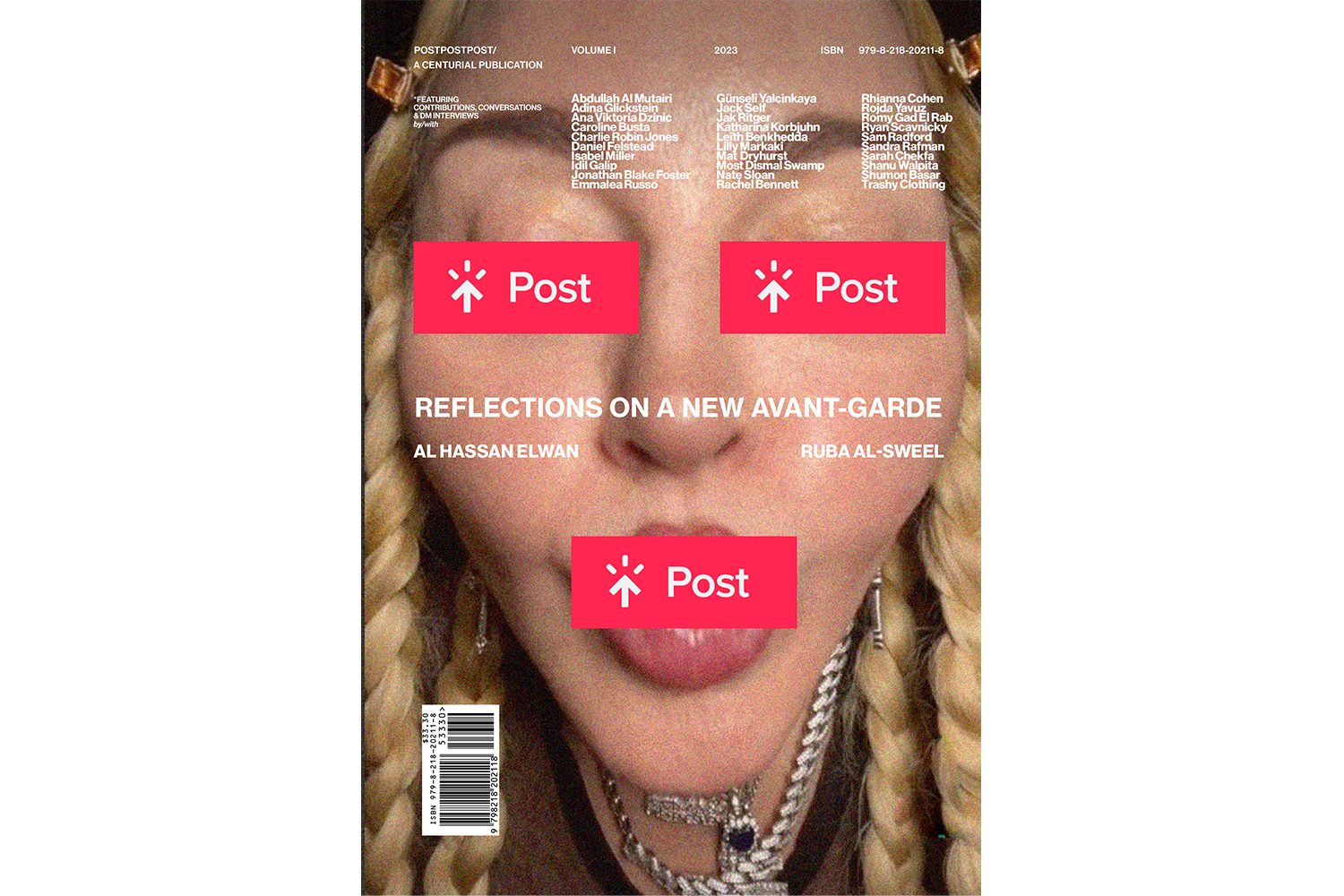

On April 2, 2022, Madonna posted a TikTok. In it, she rightfully stars, clad in a black mesh top with no bra, blonde hair in Viking-style double braids secured with Y2K snap hair clips, silver necklaces stacked around her neck, costume ouroboros, staring almost directly at the viewer, but not quite, pupils barely visible, their lids a setting sun seemingly weighed down by something quite unseen. She leans into the camera, sea glass for eyes still shyly drawn to that same locus on the screen just below center. For a split second, a simulacrum of smoke glimmers in the frame as her song, “Frozen,” a bewitching trap-pop remix of her 1998 progenitor, pours itself into the silence — a mournful ode, rescued from outright melancholy by a nimbly fingered synthesizer. Her lips, glossy and cartoonishly buxom per their casting into a permanent pucker by some fanatical cosmetician with a bimbofication hyperfixation, magnify as she valiantly attempts to eschew temporality (contort them into a duckface, that nostalgia-ridden heirloom of the early 2010s).

Such is the image that co-editors Al Hassan Elwan and Ruba Al-Sweel have chosen to occupy the cover of the inaugural volume of their “centurial publication,” POSTPOSTPOST: Reflections on a New Avant-Garde. Albeit memetically edited: Madonna’s eyes and mouth are each obscured with an eponymous fuchsia CTA button labeled “Post,” lifted from the TikTok interface. That this particular trinity is concealed feels significant: these are the regions most crucial to the memory of a face, the memory of which, Because Internet — to borrow from Internet linguist Gretchen McCulloch — we are perhaps less inclined to memorize.

***

Elwan, an LA-based brand consultancy co-founder and cultural researcher trained as an architect, and Al-Sweel, a Dubai-based writer, critic, and researcher of art concentrating on the Middle East, describe the publication as “a wealth of attempts to capture a kind of contemporary literature and scholarship that expresses a general dissatisfaction towards the self-effacing ongoing lore and neologism-coining/brand narratives of ‘end times’ that the intelligentsias often indulge.”

POSTPOSTPOST, not unlike the compulsive remixing of Madonna’s “Frozen” — as of the date of writing, four remixes exist — is a reconsideration of the current cultural moment that occupies the now, succeeding its ancestors Modernism, Postmodernism, and Post-postmodernism. Elwan explains history’s metamorphosis into the present: “The grand narrative ideals of Modernism were rendered obsolete after the real world implications of World Wars and atomic bombs, resulting in Postmodernism’s incisively critical resonance and ironic disillusionment coming out on top, only to be moderately challenged by ‘post-irony’ towards the end of the century; i.e. Post-postmodernism and the New Sincerity — that’s not in opposition to irony [but] rather claims to learn from, subsume and transcend beyond it through faith.” Yet while POSTPOSTPOST draws from these anterior academic theorizations of the cultural moment in order to self-baptize, it does so with self-awareness, shirking associations with “factual correctness or academic rigor.” Such haughty stylizations are unqualified to confront the malleabilities of meaning we reckon with today.

***

The top comment on that fated TikTok — “Is this really Madonna??” — exposes a varicose vein of unbelief that throbs dangerously throughout the corpus of the comment section. Reality, it seems, feels unreal. A miasma, better known as derealization, is in the air. Was the TikTok a marketing ploy? It wouldn’t have been the first: a few months after it was posted, multiple musicians, including Ed Sheeran and Omar Apollo, both affiliated with Warner Records alongside Madonna, attested to how their labels pressure them to go viral on TikTok.

The audience, naturally, is unsure what to believe, and this pains them because they so wretchedly want to believe. They are searching for some way to continue believing. “What is she on?” murmurs another viewer. “What is going on,” demands another. These are not questions solely being asked by an incredulous Madonna fanbase. “Over the past seven years, we’ve lost count of how many times the question ‘how is this real’ echoed in our collective subconscious,” opines Elwan, citing society’s collective inundation by spectacle and global tragedy in the conversation with Al-Sweel that opens the publication. The Madonna case, it seems, is just another one of those moments. A few discerning viewers catch on: “but have u watched it over and over there is a msg,” elucidates one. “Madonna is one of the most powerful symbol manipulators ever. I was [uncomfortable] at first, but now I feel tears in my eyes,” admits another. No crying selfie is attached as evidence, but I, too, want to believe. And tears here feel appropriate, mandatory even. For, to paraphrase the shamefully honest text-based posts that permeated the dashboards of 2010s Tumblr, now permanently tattooed unto the membranous cellophane of my psyche — artifacts which I now recognize as emblems of the post-postmodern New Sincerity movement, precursor to POSTPOSTPOST — just because we’re used to it, doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt anymore. Yet, as dutiful denizens of the Internet, we’ve learned to cope with the pain. Ironically enough, “cope” has devolved into an insult online, deployed to jeeringly “imply that someone is upset,” poking fun at the purported delusions to which they cling. “We now only respond to disasters with smirks and ‘I told you so’s,’ the only way we know how under the overwhelming weight of individual helplessness,” Elwan observes. Some may call it Stockholm syndrome, but here we call it POSTPOSTPOST.

***

The eponymous vade mecum features contributions from a diverse group of writers, thinkers, artists, and designers, audaciously encompassing 272 pages of essays, Q&As, DM conversations, and, naturally, memes: would a meditation on our cultural epoch not cede credibility sans the playful invocation of one of its defining mediums? Three essays penned by Elwan establish the POSTPOSTPOST “canon.” Canon #1, “In Defense of The Edgelord,” takes the Edgelord — that normatively irredeemable, meta-ironic antagonist of the Internet — to trial, and pronounces them innocent. For they are the ones “on the constant lookout for the edges of ideology, testing its bounds.” Canon #2, “Hello, Parareal,” discusses how reality consistently presents itself as fiction — think: the unbelievability of whether it was truly Madonna in that TikTok. Parareality thus results in “a scripted absurd theatre [that] could be only a symptom of the general collapse of many epistemological ideals and structures that were taken for granted. […] Post-truth […] unveiled the pseudo-reality beneath facades of the modern world.” The final canon, “Nothing is Camp,” argues against the cynical postmodernist’s undervaluing of radicalism due to its inevitable co-option: “the more nonsense is put out, the more incredible it feels that it’s still going.”

The rest of the publication encases this canonical skeleton with various case studies: Al-Sweel announces that “the name of this trash can is ideology,” analyzing fashion as invoked by Lana Del Rey, Shamima Begum, and Muammar Gaddafi. Shumon Basar sires a poem via DMs. Abdullah Al Mutairi scrutinizes the misfits and mavericks of the Gulfie Internet. Idil Galip diagnoses memes: “As Above, So Below.” Rojda Yavuz proclaims that “The Revolution Will Be Aesthetic.” Dream Boy Book Club editor-in-chief Jonathan Fostar performs as anti-influencer, assembling “what is the opposite of recommendations?” I write on not being desperate and why Look 45 of Vetements’ SS23 RTW collection is. Caroline Busta, Emmalea Russo, and Trashy Clothing are summoned for a Q&A.

And Elwan and Al-Sweel survey the cultural barometer as mediated by DMs with Shumon Basar, Katharina Korbjuhn, and Jack Self, among others. “Name one thing that absolutely horrifies you about the world today… You can be sincere or ironic… Why did you decide to respond ironically/sincerely? Fuck, marry, kill > Elon Musk, Henry Kissinger, Hasbulla… It’s confirmed. We live in a simulation. Who’s in control?” My brain, tainted by pixels, observes a series of participants providing answers to a preordained set of questions and cannot help but see this as a Buzzfeed quiz, but make it longform. Also, there’s no result… uncanny. I am unable to discern whether this is an act of premeditated meta-irony by Elwan and Al-Sweel or my preternatural onlineliness paranoically engendering unlikely fictions once again.

***

Interjected at seemingly arbitrary points throughout the publication are memes in the service of POSTPOSTPOST. Walter White of Breaking Bad (2008) sneering, “I am the one who knocks” revised to read “I am the discourse;” Wendy Torrance of The Shining (1980) labeled with a bountiful harvest of -cores (cringecore, trashcore, cottagecore, etc.), mouth agape, staring at a butcher knife masquerading as Post-core; Guy Fieri in a kitchen fielding the flames of POSTPOSTPOST. At times even presented in the midst of serious essays and conversations, I found their inclusion interrupting my reading: occasionally, I would have to turn back to re-read sentences prior and skip over them quickly to complete the thought they interrupted. It felt to me like the memes were sinking the rest of the journal’s incisive commentary down to a lower echelon. Is this real? I found myself thinking, searching for a reason — cope — as to why they continued to crop up over and over again throughout the tome. “As soon as you enter the system to denounce it, you are automatically made a part of it,” a line of Jean Baudrillard’s, coincidentally quoted in the text, rang in my head. Yet my bemusement evolved into epiphany as I realized the symbolic function these memes portended while re-reading the opener to the journal:

POSTPOSTPOST’s existence as an urge is what we can build a brand around. Being a brand absolves POSTPOSTPOST from having to present consistent opinions or an irrefutable philosophy of life. For positioning purposes, this makes it better equipped for the ephemeral spheres of resonance and attention rather than factual correctness or academic rigor.

If POSTPOSTPOST is a brand, then these memes are its advertisements, the mechanisms it relies upon to sustain itself in an age when companies’ co-option of memes as digital marketing can net them ten times more reach with 60% organic engagement, compared to the virgin litmus graphic’s 5%. The memes are situated on blank white pages, estranged from the content-dense feed, their traditional home, the mode of their installation evoking the white cube of an art gallery and all the intentionality imbued into it.

Advertisements have inoculated just about every experience to be had on the web, from reading to shopping to posting. And so POSTPOSTPOST’s advertisements behave no differently, the persistence and arbitrariness of their placement poking fun at the unreadability of the Internet. The publication’s cofounders — the brand’s entrepreneurs, if you will — silently wield the curse wrought upon the Internet as a meta-ironic rhetorical device vis-à-vis mimicry.

***

The intentional self-referentiality inherent to the design of POSTPOSTPOST is also apparent in its online presence: in stark contrast to the sterile, “user-centered” precepts of the standard Squarespace-powered digital storefront, postpostpost.com is an experiment in user-decentered schizophrenic web design. A white background is overlaid with an assortment of those memes-qua- advertisements, further overlaid with black italic text spanning the entire length of the screen, every word styled exactly the same, equally weighted so that every sentence performs as headline. This is the Internet, and everything is important so nothing is.

Every line is centered, a style of text alignment that is notoriously difficult to read: as it becomes exigent to actively identify the beginning of every subsequent line of text, it becomes nearly impossible to maintain the smooth reading flow necessary for comprehension. Perhaps this is an allusion to the difficulty of distinguishing reality from fiction in today’s parareal, where reams of information compete, so valiantly attempting to center themselves within our faculties as to ultimately bleed together, devoid in equal parts of context and significance.

***

“She’s ‘frozen,’ just like her song,” Page Six taunted. “Madonna’s new face is an eyesore and a complete betrayal,” the New York Post added. “This is not news,” argued Vogue, the voice of reason. Madonna as a metaphor for POSTPOSTPOST is apropos. We are frozen in POSTPOSTPOST. POSTPOSTPOST is an eyesore and a complete betrayal. POSTPOSTPOST is not news.

“Look how cute I am now that swelling from surgery has gone down. Lol,” Madonna tweeted alongside a photo of herself in February. What is the POSTPOSTPOST analog to Madonna’s post-operative recovery? Going offline? “Digitally detoxing,” as they say.

I hypothesize that Remilia Corporation, the digital collective of self-identified “Avant Net Art Extremists,” would disagree. They termed the concept of network spirituality, “a futurist embrace of experiential hyperreality found in the web’s accelerated networks” made possible by “transcendental[ly] posting,” “perform[ing] identity,” and “embedding spiritual and moral values into memes” because “we need something ~religion to navigate the cultural maelstrom of the internet.”

The cap Madonna is wearing reads Spiritually Hungry. Network spirituality, I fear, may not be enough. But I want to believe.