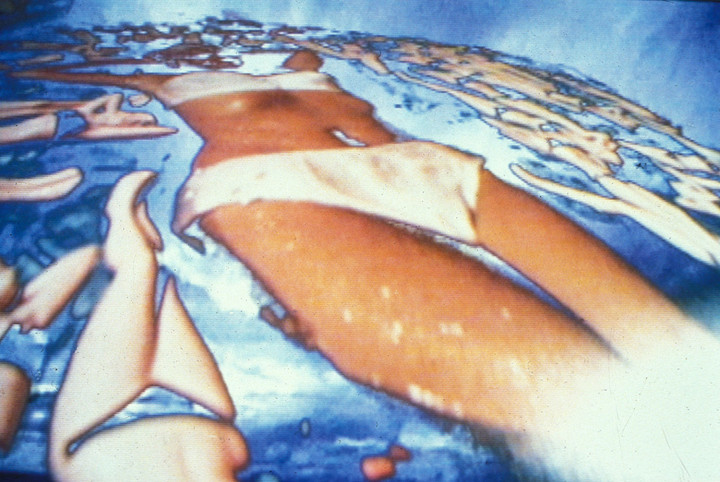

Klaus Biesenbach: The first all-surround Pipilotti experience I had was when I visited the Chisenhale Gallery in London in 1996. I remember Sip My Ocean was installed and you were karaoke-like singing the lyrics of the Chris Isaac song, Wicked Game. I couldn’t get that song out of my head for a long time and the music video with Chris Isaac and Helena Christensen making sweet love on a tropical beach was still very present when I first encountered your piece. You connected the well-known music with sequences that connected your body with the oceanic feeling of being one with the world — being one with the pop world as well as being one with the world of nature and your own body. I laid down right in the middle of the exhibition space, quite close to the projected images, and I cast a shadow on the projection wall and the backside of my head was illuminated with the blue light of the video projector. Was this installation a new chapter for you as an artist?

Pipilotti Rist: This installation with that song interpretation, produced together with Anders Guggisberg, was actually born at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam a year before. It took me 3 build-ups ’til the installation became so reduced. The symmetry seems logical. The ‘unfolding in the corner’ is linked deeply with our body, in which most parts are quasi mirrored. I assume that that fact feeds our deepest craving to be synchronized with others. This wish is linked with our love for fluids and water. An installation is a possible collective body. And our body is a lot of water.

KB: In the late ’80s I had the feeling that mass media would create one single huge world audience — everybody would listen to the same Madonna or Michael Jackson song, or Joy Division or The Cure records, depending on which group of adolescents or mentalities one felt close to. The Gulf War of the early ’90s brought the power of CNN to my attention. I clearly remember camera shots taken from the top of a missile before it hit its target. TV seemed the universal language of the new upcoming era. Were you influenced by television, especially MTV, during this time?

PR: I wouldn’t call TV a language, rather a distribution technique for different film styles, even if TV has influenced our oral and body language. I see it rather as a static box, which absorbs our attention and our potential life. I have no TV at home to “protect me from what I want” (thank you Jenny Holzer for this and other wonderful sentences!), ’cause I have to watch too much of what I don’t want, until it gets to what I want.

Unfortunately there are also not many music videos broadcasted anymore. I consider some of them as great pure juicy artworks, which stand in the already older music and experimental film tradition. We have the possibility to see such works in program cinemas like the Filmpodium in Zurich (which I visit far too little) or in a poor resolution on the net.

KB: Years later all these TV channels — local or national versions of MTV or news stations — fell apart again. One could easily miss the idea of a center that was visible for all. One of the last big MTV video memories for me was Madonna’s Take a Bow. In it, Madonna is in love with a bullfighter, and she watches his fight on a TV in bed and she basically has sex with the TV set. She pulls the bed sheet over the TV monitor and becomes intimate with the image emitting from the machine. I felt on a mainstream level she expressed much of the impression that I had at the time — that media had become prothesis or TV had developed a libidinous object of desire. Did you ever see this video? If so, what was your reaction?

PR: I’m sorry, the video is only vague in my mind. But it’s true, mass media tries to substitute social elements. They are constantly talking to you, but with no consequences and no stinking feet. I also have to force myself not to watch too much in this two-dimensional computer screen. Our brain is evolutionary and not prepared for many of the uses of electronic devices.

KB: In the mid-’90s, I wanted to create a submarine with you, unfortunately that never materialized, but I do remember your piece in the 1997 Venice Biennale, Ever is Over All, which is now in MoMA’s collection. I felt it had become much more narrative.

Now you are directing your first feature movie. Was the ambition of creating new narratives always something that you felt motivated by?

PR: To evolve myself I had to make a feature film. A feature film accounts for a certain narration to keep the watcher for 80 minutes. A narration presupposes a professional team and that needs a budget, which you only get for a narrative work. That sounds conservative but it is effective and challenging. A video installation can live on one single idea but a feature requires one or more for each scene. In the cinema or in front of the TV people should thus watch in one direction. This ritual means for me just another condition and I treat the cinema room as an installation room. I also consider all the living rooms with TV sets as the biggest video installation in the world.

KB: The piece at MoMA, Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters), 2008, is very much an installation like the early Sip My Ocean — it is a broken narrative full of associations, mirrored images and partial loops. I remember when I first owned a video player that had more functions than just play, stop, forward, and rewind, I went through your videos that I had in my office and I freeze-framed them many times, only to understand that basically every single frame I focused on could function as an image in itself, composition wise. Is this one of your techniques or does this just happen?

PR: The final material is a product of a longer process. This consists of organized, conscious, moving camera work with a lot of footage on one side, and the selection and treatment at the editing table on the other, which takes the most time. I regard video as moving paintings, behind glasses or caressing away walls. Since the third dimension is lost in film you must make it up with the quality of the composition of the images, with rhythm and with sound and music.

KB: In 1997, at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, now MoMA’s affiliate, we installed the smallest piece of yours together in the entrance lobby, Selfless in Lava Bath. The piece is still installed in the P.S.1 lobby. Now we are realizing a large-scale commission in the atrium at MoMA. And, you had a monumental installation at St. Stae Church in Venice. Does size matter?

PR: Size is just another given condition of a room I have or want to deal with. To do an installation in a little café or at MoMA has the same value for me. Large rooms, let’s say over body sizes, refer to collective experience and to meetings. In the case of the church, size also means a proof of the alleged grandness of God in contrary to our littleness. But at the same time, these places remind you to forget your small problems, which are relative to the ones of the others. The Marron Atrium at MoMA, with its generosity of space, is also a room of passage where the visitors flow to the different galleries. I want also to serve that use.

KB: I was just at the Shanghai Biennale in China, a place where we both have worked together. I observed the audience quite a bit, because with nearly every cell phone having a camera and digital cameras being so cheap and ubiquitous, nearly all of the visitors looked through the camera lens to see the art works. They looked at the works on the little digital screen and saw how the exhibited artwork looked on the wall or the floor, and then they took a photo and moved on. Does this mean there will be thousands of new multimedia artists soon, or is that just the average consumption mode nowadays: to see only if you look through a lens?

PR: In the last 20 years technique became cheaper and smaller, this has a big democratic potential. Where it is not developing a bit is the postproduction, which needs a lot of time, intention and concentration. The know-how like camera work and editing is already and hopefully more and more a part of ordinary school education. My memory of the Shanghai Biennale in 2002 was a bit different than yours now. The audience came in crowds and was so extremely interested and curious that I had to cry with joy. Maybe the visitors enjoy now the shot works at home.