Good artists can be easily misunderstood, but only a few excellent artists — expanded artists — are pleased with this misunderstanding and have the ability to take advantage of it. Cecily Brown is, no doubt, one of these artists. We assume that since the ’80s, painting has “represented a fragment of a more complex situation”1; perhaps this is illustrated by early watercolor animations of sexual penetration made by Brown and shown in New York only last year. Her oeuvre can be associated with the practice of Kippenberger2 or the eponymous ADS series by Jeff Koons.3 With an ego that is less visible (but no less powerful) than that of one of the aforementioned male artists, Brown is a hardcore performer who smartly hides her acts behind her paintings. In other words, her canvases are energized by her performances, which are only unofficially documented by the press. We all know about the article she had in Vogue, or when she posed in a bikini for a portrait by David LaChapelle in Interview.4 To be precise, this attitude was inaugurated also in on another platform. It was 1999 when the blockbuster exhibition “Sensation” confronted the American audience at the Brooklyn Museum. Even if the newspapers’ attention had been focused on the scandalous Holy Virgin by Chris Ofili, another big deal was happening that night. At the opening of the “Young British Art”5 survey, English-born, New York-based Cecily Brown showed up in a dress that could be compared only with Cher’s outfit when she attended the Academy Awards in 1987, when she won the Best Actress award for Moonstruck. The picture of Brown, wisely captured by Artnet’s Paul Laster, can be considered her real breakthrough, while the event is a seminal point for her practice.

Aware of this certitude, what could be the difference between the songs of Britney Spears, whose tracks have half their power if considered without her teen sensation image (albeit no more),6 and the art of Cecily Brown? Could we consider Brown’s practice as one of the smoothest methods to simultaneously please and denigrate the art system and its resolute desire to produce commodities? How many artists are able to proceed in a paradoxical situation, where their practice can be seen as a continuous gambit towards the ephemeral while the work has all the elements of a masterpiece? Speaking of masters, we need to recall Brown’s attitude toward her predecessors.

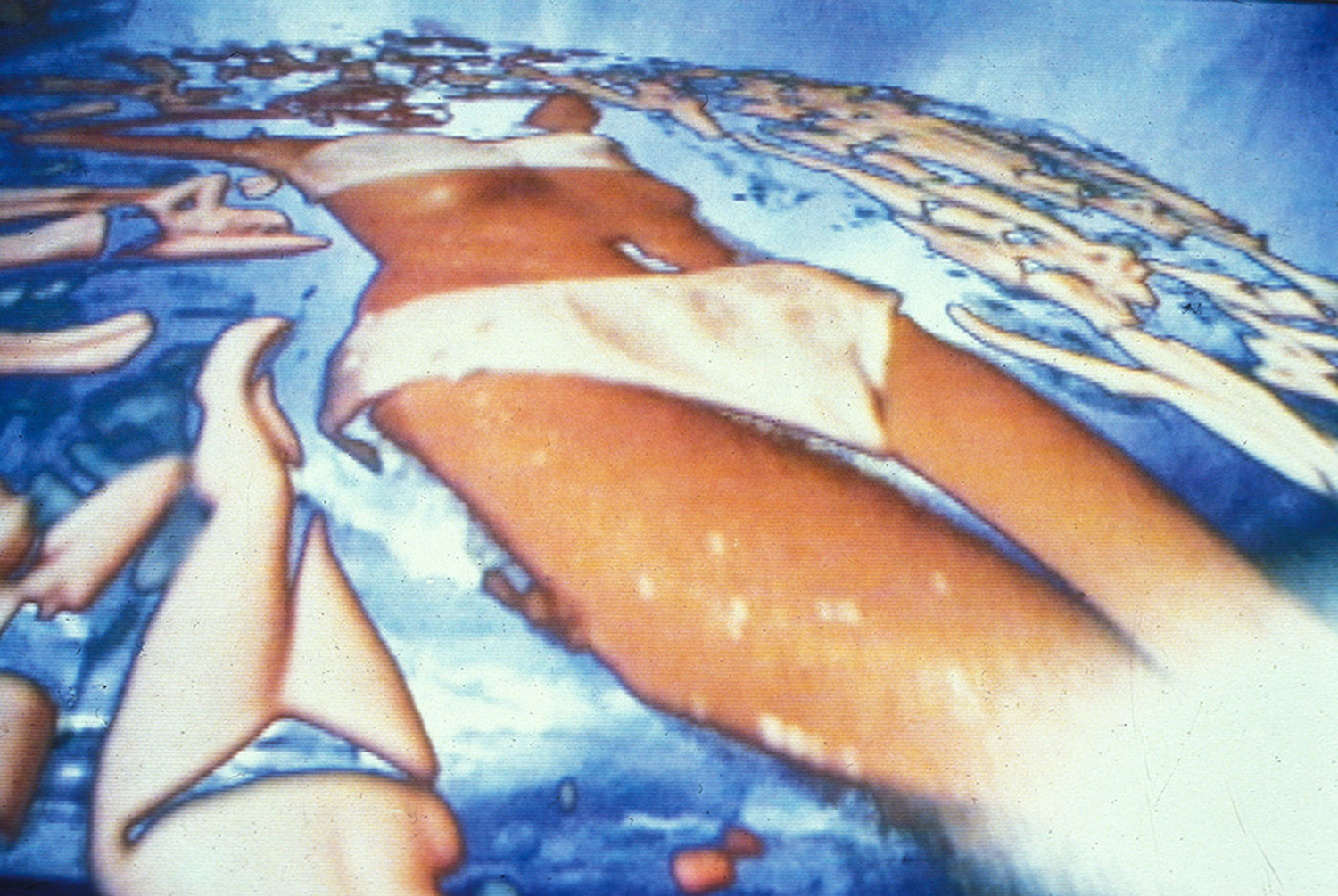

“Cecily Brown’s photographs in Vanity Fair, which where taken by Todd Eberle, show her reclining on a studio floor that is splattered with paint and dotted with cigarette butts in a manner that would have done Pollock proud.”7 From championing to sampling — subverting the machismo of painters once supported by Clement Greenberg (Pollock, and above all De Kooning) and their British friends Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon — Brown is transforming rudeness into sensuality, violence into glamour.

In this sense, Bacon can be taken as the most intriguing of her detournements: Cecily Brown is the daughter of the leading art critic David Sylvester, who was influential in promoting Freud and especially Bacon,8 with whom he did several interviews. In a sort of “post-post”9 and reversed Oedipalian counterattack, Brown is manipulating her father’s protégés, underlining that she has learned the lesson better than many art historians, and has re-drawn a new chapter — an insane hermeneutic that turns Masculine Modernity into a feminine seductive conjugation of Gianni Vattimo’s “weak thought” (“pensiero debole”).

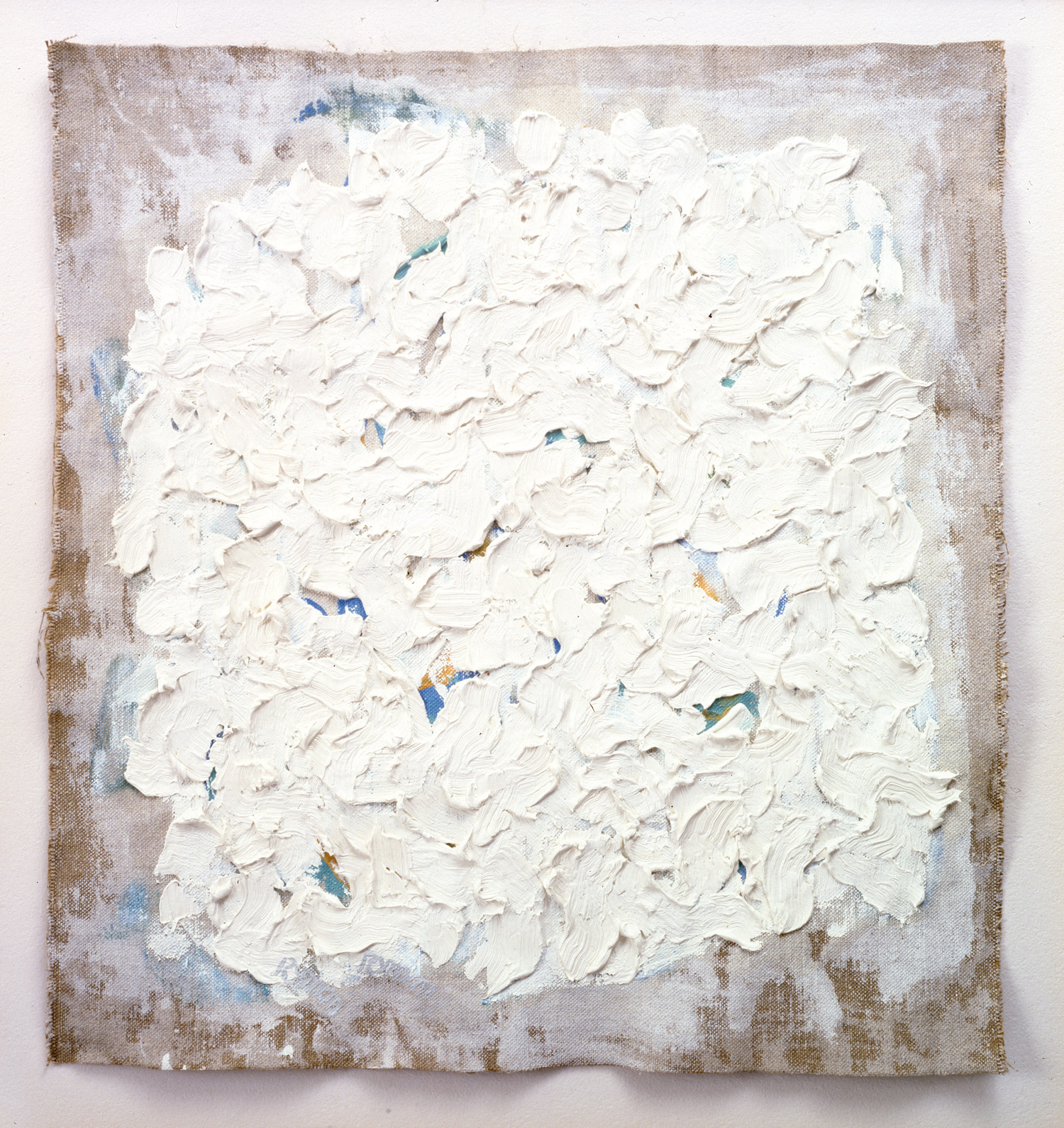

Confirming the example of the expanded nature of her practice and her talent for looking at and understanding her colleagues and predecessors, Brown’s Flash Art essay “Painting Epiphany” is an ode to the pleasure of painting and a sweetened way to herald her “Fuck off macho painter scum” approach.10 How can we decode all of these bizarre and almost degenerated interpretations presented thus far? What is the key to decoding Brown’s oil on linen compositions in this sense? Are the artworks the real core of Brown’s practice or is it our dreaming of her, lying on the floor of her studio? To quote Jean Dubuffet (the father of all the expanded painters), “Art does not lie down on the bed that is made for it; it runs away as soon as one says its name; it loves to be incognito. Its best moments are when it forgets what it is called.”