The paintings of Leidy Churchman (b. 1979, US; lives in New York), Van Hanos (b. 1979, US; lives in New York) and Alan Michael (b. 1967, UK; lives in London) trigger a whirling dialectics between the reality they depict and the concrete world they inhabit. By filtering a realist imaginary through sly representational and framing gestures, the paintings convey a subject matter that interrogates strategies of image-making on the canvas. They render content in which a potential iconicity is compromised by hints of the creative process. Here, Churchman, Hanos and Michael talk with Michele D’Aurizio about appropriationist strategies in their painting practice, labor production and the possibility of making new images in our visually saturated world.

Michele D’Aurizio: Your painting practice is grounded in appropriationist tactics. The sources of your subjects are multiple and diverse, and yet they denote affection for specific visual repertoires. The eclecticism that differentiates your respective subjects echoes the kaleidoscopic visual culture of our time; simultaneously, however, I feel that your individual approach, almost in opposition to the dynamics of image dispersion, lies in the exercise of framing an “imaginary.” This imaginary, it seems, does not stem from your own imagination; rather, it exists as a factual system of references that fosters your belonging to distinct cultural landscapes and collective styles. In other words, it ties your paintings to the concrete world. Do you agree with this reading? How would you describe the visual repertoire that precedes your paintings?

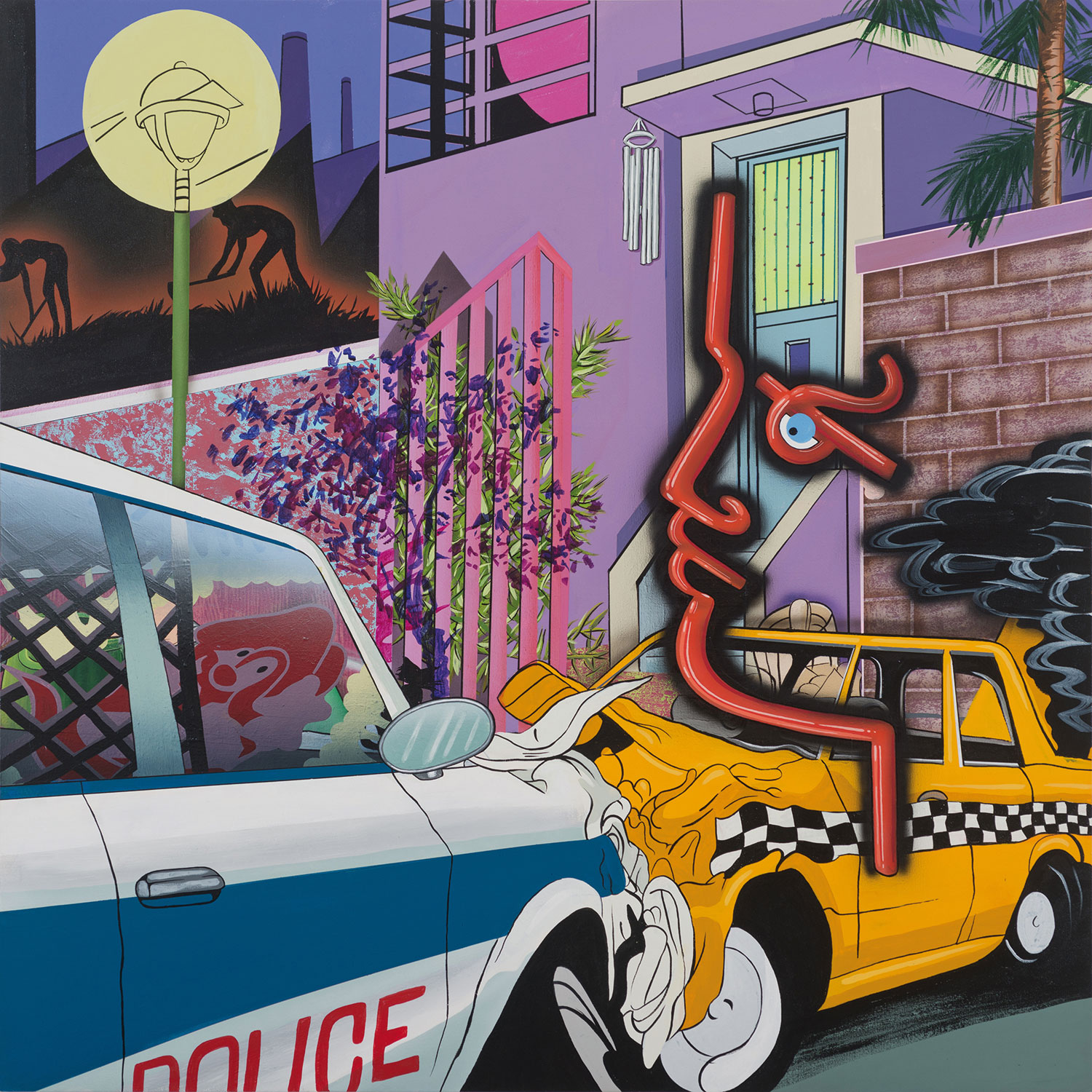

Alan Michael: I don’t think art is a mirror: realism is symbolic — it represents a realist subjectivity. Using a retarded format of representation, photorealism is, in my case, the opposite of affection: I don’t like the format per se but it’s useful. The originators of the style had nothing of interest to say about the world they were displaying, but endless projections can be directed at this void. I used the style to display brand-products like BMW Minis, Accessorize stores, exhibition signage. With the plan being that the car paint surfaces and the shop windows would reflect surrounding real estate, restaurant interiors, etc.

Leidy Churchman: I just put down an interview by Lisa Ruyter, and she says, “appropriation as a mode of representation has completely changed in meaning over the last twenty years. Jeff Koons looks practically Mannerist now — it’s not at all what it meant twenty years ago. There’s nothing punk about it anymore.” Some remarks on Mannerism: common characteristics of many Mannerist works include distortion of the human figure, a flattening of pictorial space, and a cultivated intellectual sophistication. And so I think that I don’t like Koons’s work very much, and maybe because in a weird way I have never been able to see beyond and endure all the projections of excellence. His work is seductive and exhausting. I have liked to pick oddly seductive and popular pictures to paint, but so that I can get very close to the representation of that thing. It becomes like the walls that would surround you if you sat in a closet for a long time… You would get to know them. And it would be weirder than the veneer of capitalism.

Van Hanos: Appropriation on some level is everywhere. Think back four hundred or more years ago, when seeing an image happened so rarely, maybe even once in a lifetime. The severity of that is something I want to consider more when making work. We are all beyond saturated; images function differently, have less potency. Many say image production is just a closed loop, that it’s not possible to make new images. There’s a lot at stake, but I’m optimistic.

I think in regard to appropriation, it’s more felt than actual, as is acknowledgment of the internet. It’s not an overt subject, but it influences how images are worked through, dispersed, and how the meaning of the images can change depending on which platform they’re viewed on. That isn’t to say that I haven’t used found images. However, it is very rare. For me, all the paintings that come “from images” are from photographs I’ve made myself. In the past, I have tried to pull from images I love that I’ve found elsewhere — but I find my relationship to them just isn’t intimate enough to push through to paint. Possibly this is something that will be incorporated more as it relates to the larger project of indexing painting. I’m just starting at it all, so it’ll be something that evolves in time.

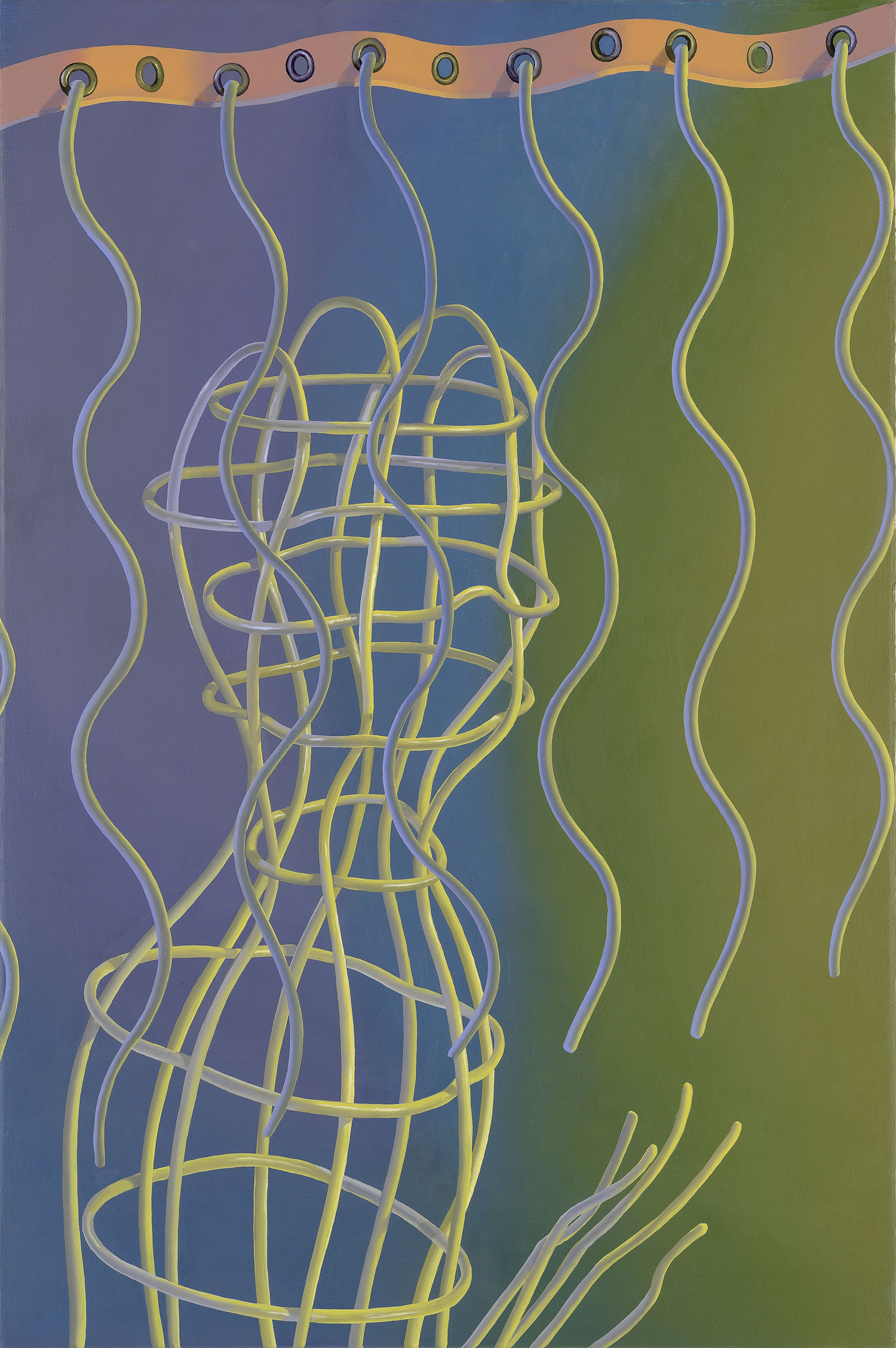

MDA: It seems that your subject matter is a pretext for a kind of inquiry into image-making on the canvas. In the end, the artwork plays both with the “iconicity” of its subject and with the inner structural configurations that make it an “index” of the painting process. I think about the interplay of transparencies and mirrorings in Alan’s paintings (see Untitled (High Street), 2007, or Regent Street, 2009, for example); or about the exposure of the photographic equipment and the studio devices in Van’s (Painting Talia in the Studio, 2010; or A, 2014); or, in a less direct way, about the tension between the bi-dimensional artifact and the “bodiless” graphic artwork in Leidy’s (Pizza Box, 2013, or 19th Century Flayed Elephant, 2015)… Can you elaborate on these visual and conceptual “gimmicks” at play in your paintings?

AM: The subject matter is a checklist that includes formal stuff, like reflective surfaces, transparencies, etc. — paradigms from reactionary photorealism and all the associations leading out of that. I wanted to represent reality, the capitalist rapture, in a particular manner; so I looked at painting formats historically suited to this. The idea was to represent consumer archetypes in a credible way — I mean, in a way that looks believable. I found that the style of painting was something I could replicate while also producing texts and other types of work. It’s interesting to look at it afterwards; adopting a style is like having someone else working for you. The painting process, such as it is, is simple and all about setting goals and time-scales.

The world has dissolved, but I think it’s interesting to represent things as if nothing has happened, as if continuity exists. The information presented is, on the face of it, useless, and so could be said to be invisible to the class of information experts the work seeks to criticize.

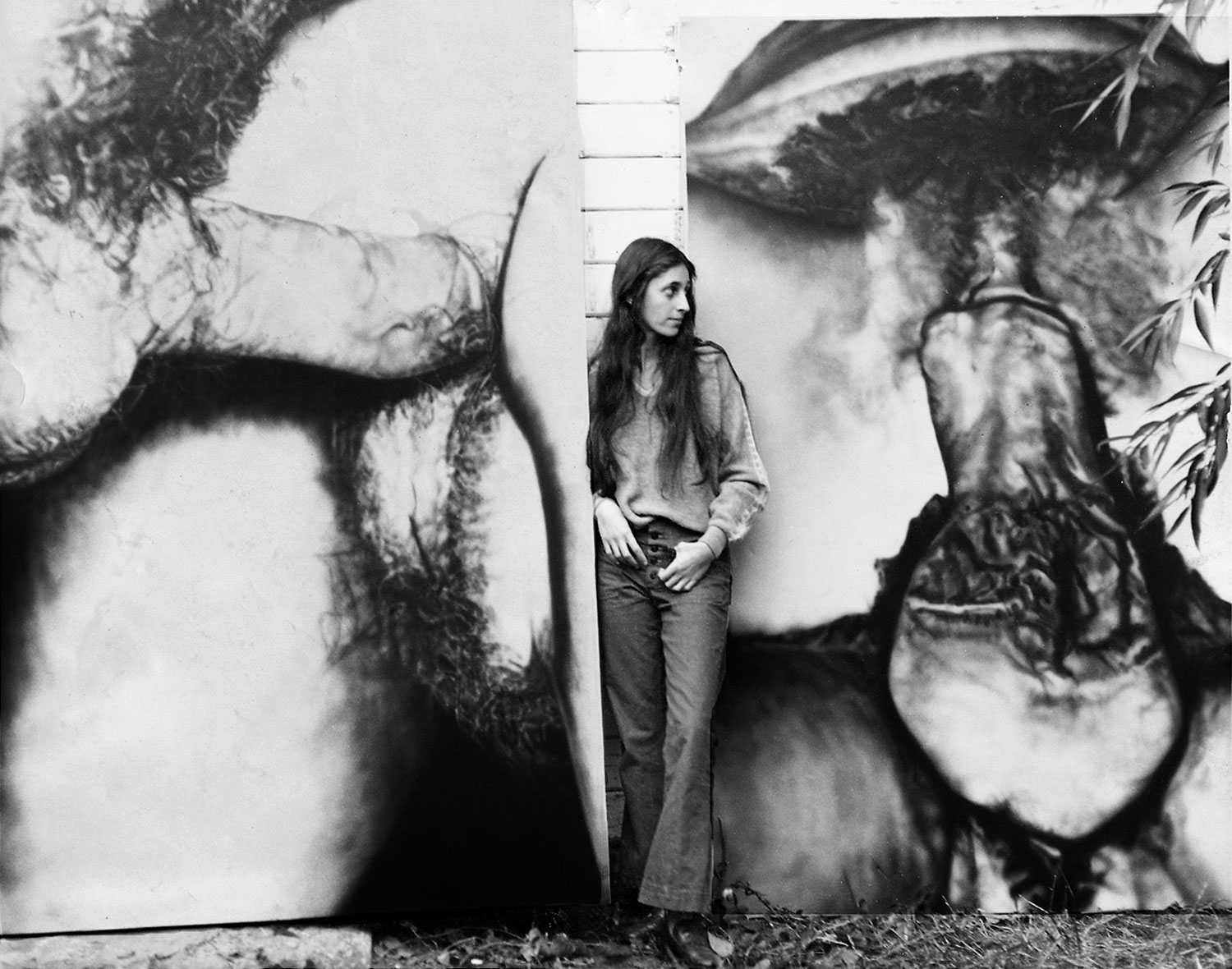

VH: Those photographic cues are meta-references. My hope was they function as the fourth or fifth wall does in theater or film. There are two related paintings from 2010 that feature the photographer Talia Chetrit — her camera was used to get the picture. The first, Portrait of Talia Chetrit with Lilly, has the photo equipment — as does A. Both show a moment that would be very difficult to capture by the eye or in observational painting. I didn’t want to front that it was made in any other way than it was; I wanted to show all the tricks I used. The second, Painting Talia in the Studio, also came from a photograph. This time the light source was a projector. It’s the source image for the first painting projected over the studio while the painting was half completed. I wanted the paintings, when shown together, to collapse that time — in one you’re looking at the other unfinished. They hopefully become fractals of the process and themselves. The photo and still projection speak to the slowness at which I want painting perform. To take a stance for stillness, to slow down to a rate where content unfolds through time.

LC: I think Pizza Box is a good piece that you brought up for this question. When it occurred to me that the pizza box would fit completely inside the entire painting and present itself as an exact-ish object, I got very excited. “Your Freshly Baked Pizza” it says, with creamy white and forest green — so bold and secure. The painting is in fact a delivery — right to you. I love that simple arrangement. “Here.” Finding the way for something to fit inside — framing — is my biggest concern. To me it’s like making the bed. How can the picture get tucked in?

With 19th Century Flayed Elephant I decided to make it slightly off kilter, and add a bright yellow frame to highlight that this object is moving. The picture comes from a Tibetan rug and is a very sacred object. It didn’t seem to want to be framed too tightly. The piece has so much wisdom and wild awareness; it actually took a lot for me not to get frightened of it while painting it — touching it.

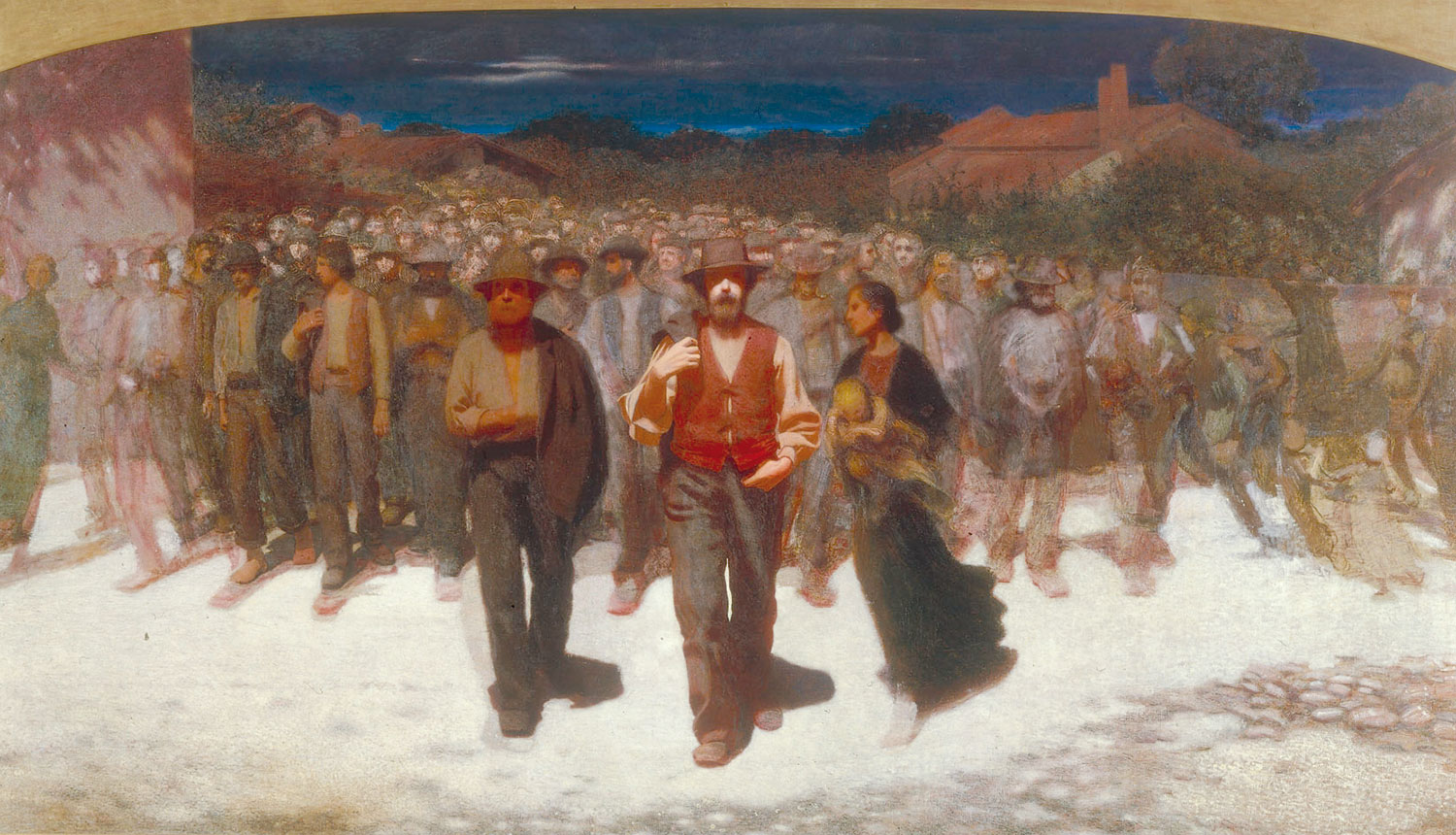

MDA: In line with the methodological issues raised above, I’d like to learn more about productive strategies associated with “copy” and “repetition.” In the case of Alan’s practice, the reiteration of the same image on several canvases produces differentiations in the color tone of the image, such that full spectrum often fades into grayscale (see Streetwear in Drapers, 2011); or it highlights minimal but undeniable incongruities in the reproduction of the image’s details (Natwest, Anon-nets, Bornagain, 2013); or it “reframes,” or “rescales” the original image (Alan Michael Publicity Agent, 2014). Leidy has instead repainted historical paintings (Rousseau, 2015). While Van systematically produces “versions” of his owns painting (Candle Maker’s Lamp, 2008 and 2012; or Portrait of Talia Chetrit, 2008, echoed in Painting Talia in the Studio, and Lilly’s Gaze, 2012). These gestures can’t but refer to a certain fatigue implied in copying, and thereby raise issues of labor production in creative work. What’s your position here?

AM: These characteristics are definitely suggestive of work. Hating work is definitely not cool in society today, but it ought to be, as a social image, since people are defined as being productive or not. I hate work. Those paintings you mention came about because I’m interested in reproducing methods for generating content and images that would be outside of the spectrum of coded research presentations. Creative identities and an affinity with easy flows and circuits of data were the main topic. It’s hard to discuss because it’s about wanting something to happen that’s negative. The material is supposed to have the general appearance of specialized information but selected in a kind of panic.

Given my background of making works referencing photorealism, I started to synthesize this with modes of authoritarian Pop art — Richard Hamilton and others — to think about a parallel consumer-object-quoting movement. It never really integrates, which I find interesting. The paintings Streetwear in Drapers, in fact, are silkscreens with oil over-painting, and the variations in the different versions are there to point to their seriality.

LC: I am always trying to get close to the visual languages of our world. Art is a big part of that. I want to be with the paintings that have frightened me in some way (I might someday want to play with a Peter Paul Rubens body). You can get a very intimate look at a work in the museum or gallery but you must leave it there. I want to go home and get in bed with them. But it’s funny, you go home and all you have is maybe a book of reproductions or the iPad. So I go to paint it. A painting is perverse — because it’s made of muck and brains. It’s such a mess. You are there in the muck with the intention to learn the painting you’re painting — and stay with it until it haunts you like you wanted.

VH: It’s something that came naturally: I taught myself to draw by copying. It left me with a range of ability but not much of a style or interest in choosing one. Working this way helps me understand an image, or try to get some meaning from it. The copies started after grad school, making gifts for those who helped me get through. I started by making small paintings of the details of paintings I had previously made, parts that were favorites of these people. It was a way to warm back up in the studio — nothing that serious — but ended up becoming something that plays a larger role now. I like to think of how many paintings were born out of that half-a-second moment the camera caught. How one can relive the same moment for a lifetime. It ended up amounting to my first solo show, which felt appropriate and hopefully unique, and a little funny to have a retrospective of details as a first show.

Candle Maker’s Lamp is something I plan to paint every four years — maybe it’ll culminate to be the last show I make? As of now it’s an experiment; so far I can see I’m growing as a painter through it, but I imagine at some point that won’t be an interest. It’s hard to say. Being so slow, it’ll take a lifetime to see. The image was taken with a 4×5 camera, so there’s almost infinite potential for detail if that seems interesting. Initially, I thought the object was best presented as a ready-made sculpture, then I thought it should be a photograph, then a painting — I like that evolution. It shows how much consideration goes into any work. Overall I thought it spoke well to the medium, about light production, or its history: it’s a lamp that pays homage to candle making.

MDA: What is your concern in regard to the fact that painting is the most commodifiable of artistic media? I mean: in commenting on the world of commodities you end up delivering a “thing” that because of its economic and cultural value cannot but trigger a vicious cycle. In a similar fashion, your own images fuel the collective imaginary. How do you envision specific display and distributive strategies for your paintings? And how do you foresee the life of the painting at the end of its journey?

LC: I guess what I think about a lot is how much I love to see art that was not made yesterday — I love going to museums to see older work. All I want to do is look at Hilma af Klint and learn from her. And maybe that is why I am drawn to painting in some ways. It is exactly what it is. So if you can find the opportunity to see it in person, there you are with a Peter Paul Rubens, just as it was, and still is.

But yes, now art is hemorrhaging from biennials and fairs. I sure do think about that. I agree a lot with Van’s remarks. I feel similarly. I like to concentrate on our secret lives and recording those abstract traces through our work and our viral relationships. The practice is ancient and worthy, and all may be lost — or not.

VH: That’s something I have thought about way too much, and I have been crippled many times by it. I was in Ross Bleckner’s studio when he said something to the effect: “We’re just dragging more useless garbage into the world — in mass if you keep doing it.” I was a young man, maybe twenty-five. It had not occurred to me that this problem would persist. I was relieved he shared this, but thought Ross surely had an answer, as any mature artist must. My naivety didn’t allow myself to consider it gets harder over time. The more work you amass the easier it is to keep going and simultaneously the harder it is to justify. I maintain that my hands are smarter than my head — they don’t have this problem.

Another way I’ve evaded this is to consider that what I’m making now is an exhibition. The paintings then become elements for a larger goal. In that, showing work in white cubes, however necessary, can be crushing. I don’t think it’s a healthy or sustainable way to work. I actively look for other points of origin to produce the work. In the case of galleries, it’s easier for me to think of who I’m working with to make an exhibition, all the work they’ve put in, all the artists who have shown there before, the work they have contributed. Overall, the necessity of the issue has made showing more personal but maybe more difficult, too.

AM: In my experience, the economic reality of the artist-dealer-market relationship doesn’t have much in common with real-world trade transactions. It seems more like something out of the pre-industrial age. Or maybe somewhere between a black market and luxury goods artisan manufacture. Plus there’s the position of the artist and the persona factor to add to the equation, plus or minus. There are obviously a lot of parallel markets going on simultaneously which don’t sync up, worlds that are not necessarily communicating. And without a broker of some sort — a gallerist, a curator, a critic, the network — paintings are non-commodities. I heard someone talking about how they are going to get into self-representation the other day. I’m sure that’s the way forward.