In “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” (1958) Allan Kaprow famously wrote about how the abstract painter created an environment from his paintings in which the edge of the painted support met the ground at the artist’s feet: “With the huge canvas placed upon the floor, thus making it difficult for the artist to see the whole or any extended section of ‘parts,’ Pollock could truthfully say that he was ‘in’ his work.”

The 1998 LA MOCA exhibition “Out of Actions” took Harold Rosenberg’s interpretation of that post-Pollock state of painting — the canvas as “an arena in which to act” — as its bass line to examine the relationship between the painterly gesture and the body, seeing painting after this point as the result of a ‘performance’ of making. ‘Acting’ might be defined in this context not in a theatrical sense, however, but in an existential one. To paint became a way of marking the fact of one’s existence — the physical register of one’s body against a resistant surface that could bear witness to a passage of action via permanent tracks, daubs or stains.

Expressionist in character, this action-driven notion of painting as performance equates the inner soul of the artist with their physical trace, proposing the body as an instrument or physical mediator. It is a line of interpretation that runs from this reading of Pollock via Gutai in Tokyo and Vienna Actionism, playfully perverted in parallel by Yves Klein or Carolee Schneemann and later pastiched by Julian Schnabel, Paul McCarthy or Matthew Barney in his early work, Drawing Restraint. Deepening this notion of expression both to propose a literally indexical — and highly symbolic — relationship between the body of the artist and the resulting ‘trace,’ and to critique any assumed ‘universality’ of the body from a gendered or racial point of view, Ana Mendieta, for example, iterates the painterly gesture in blood in Untitled (Body Tracks) (1974): drawn as the artist drags her cut hands across a white wall. David Hammons, likewise, made his series of grease-on-paper “Body Prints” in the ’60s and ’70s. Wide ranging in intention, nevertheless, these works have in common an extenuated fetishization of abstract painting as gesture, further emptying the medium of its former narrative or representational capacity in order to focus on it as direct, in some cases ‘automatic,’ expression. This approach to painting plays upon the model of the artist as an isolated, private self whose subjectivity might be expressed externally, but whose language lies outside of other registers of representation: either in a cryptically symbolic realm or secondarily, where the pastiche or critique comes in, in a self-referentially art-historical one.

It is possible, and productive, to think differently about the relationship between painting and performance if the idea of being ‘in’ the painting that Kaprow attributed to Pollock is turned on its head. One might think about a state of engagement with painting and image-making pivoting around the ’80s in which the capacities of painting are, somehow, ‘in’ the artist; as pictorial capacities for self-presentation and self-invention, and for transformation of one’s environment. This approach invokes a different set of signifiers that painting, historically, might bring into play.

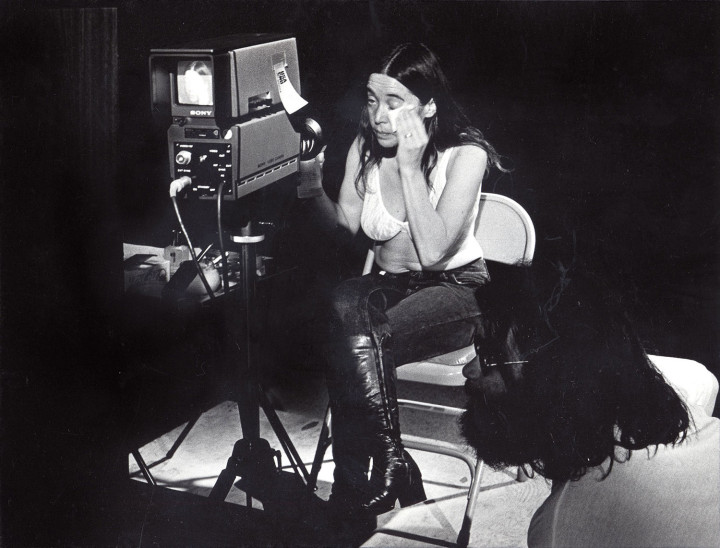

Eleanor Antin’s Representational Painting (1971) makes for an alternative starting point in this vein. To invoke ‘representation’ makes for a perverse return from then-dominant abstraction to the idea of painting as illusion: a prized goal in the traditional ‘story of art’ which goes as far back as the Greek legend that theatrically invokes a contest between painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius in which a bird pecks at a painted bunch of grapes in a still life. In this work, though, Antin also invokes illusion as a form of masquerade. Far from considering the act of painting as a register of the fact of her existence, Antin’s video comments on paint’s capacity for depiction and modulation using subtle gradations of color, form and line, and considers how one’s own mediation of self image might be caught up in that. Rather than presenting the painted canvas as evidence — its abstract traces as the after-the-event ‘scene of the crime’ — Antin’s video makes us think about painted space as a different kind of arena in or through which the subject could act: a space for ‘making up’ as both the application of lipstick and eyeliner, and the conjuring of fantasy and invention.

Antin’s video, showing the artist in the process of applying make-up to enhance her ‘feminine’ look cosmetically, implies a doubled surface to the image of her face as it registers on the videotape through a passage of time. Interfering with the idea of an ‘indexical’ link between the documentary record and the act, the piece of work foregrounds a productive gap between Antin’s real appearance and her painted one. It is a witty swipe at the forbidden territory that ‘representation’ in painting then represented: a readymade application of its techniques put to the service of approximation to a feminine ideal that was, on feminist grounds, then equally forbidden to feminists.

In The Painter of Modern Life (1863) Charles Baudelaire wrote approvingly of the magical artifice at play in the feminine practice of ‘maquillage’; of its capacity to conjure a ‘supernatural’ appearance in the wearer. Baudelaire challenged the 18th-century belief that all ‘good and beauty’ derived from nature, proclaiming conversely that “Everything beautiful and noble is the result of reason and calculation.” “Maquillage has no need to hide itself or to shrink from being suspected,” he continued. “On the contrary, let it display itself, at least if it does so with frankness and honesty”.

Antin’s idea of ‘representational painting’ like Baudelaire’s praise of cosmetics refuted emphasis on the ‘sacred’ or ‘eternal’ in favor of the secular and constructed. Antin’s staging of painting as maquillage, opens up a way in to consider a number of artists since the ’70s and ’80s who have embraced the arena of painting as a space of masquerade. Not least of these is, of course, Andy Warhol, who not only created a number of images of himself in a blonde wig, eyeliner and lipstick, but whose camouflage motif appeared on many of his representational pictures, including self-portraits, and whose famous proclamations on the subject included, “Everything you need to know about me you can see on the surface of my paintings” and — when asked if he had given up painting later in his career — “I paint my nails every day.”

Painting as masquerade, after Warhol and Antin, might take the form of camouflage or ‘drag,’ and expand to incorporate other illusionistic forms of conjuring: as trompe l’oeil or as ‘set painting’ creating a habitable mise-en-scene. These approaches to painting do not testify to the factual presence of the artist who made them, but rather imply a particular perspective or point of view, or a world created from aspiration or fantasy that the artist is immersed in. Painting, here, becomes a means of opening up a space of invention that links action to environment, but through the screen of image-based representation.

The exquisite combinations of painted and real interior space that are staged in A Bigger Splash (1973), the fantasy documentary about David Hockney — merging views of pictures on canvas with shots of his flat and studio — effect a fictionalized blurring of art and life that is also quite different from Kaprow’s. This approach to the theme transposes the artist’s literal engagement in scene-painting after his first set designs for Ubu Roi in the ’60s, and on to his many opera sets from the ’70s, into the realm of his daily life as a facet of his artistic practice: expanding the notion of fabrication that energizes his brightly colored and abstracted brand of ‘realism’ to cloak his whole world in possibility. In the late ’80s and ’90s, the work of Karen Kilimnik, likewise, took the notion of ‘scene painting’ borrowed from classical ballet as a pretext for returning to the forbidden terrain of representational painting, conjuring a quasi mythological world spun around the artist’s immersion in a world of feminine fantasy.

A number of artists of the next generation borrow from this idea of painting as an enabling ‘medium’ that opens up a liminal, fantasy space. Cologne-based painter Kai Althoff’s first installation was titled ‘Workshop’ and included painting, performance and music, but the industrial image conjured by the idea of the ‘workshop’ was countered in the detail of the piece which included cut-out images of beauty salons, conceived of by the artist as spaces of creative possibility, and linking his painting practice with the performative site that the situation opened up. In different ways, Pablo Bronstein, Spartacus Chetwynd or Nikhil Chopra, likewise, anchor performance practices against the making of pictures. Grafting the capacities of painting and drawing to live explorations of presence, they treat the medium as a space of invention that opens up a window into a parallel ‘world’ inhabited by the artist, or performers cast to embody invented personae and vision. Bronstein’s choreographic interventions in real spaces, such as Plaza Minuet in New York (2007), play out in real-time the fantastical elaborations on architecture that he draws and paints. Mathilde Rosier, the Düsseldorf collective Hobbypop or Ryan Trecartin expand too upon the idea of painting as stage-setting cum maquillage by literally integrating painted canvases into performance situations, often made for video, so as to signify a blurring of invented and real space in which participants might ‘act out’ without inhibition. Trecartin’s I-BE AREA (2007) shakily registers a chaotic, semi-scripted drama performed by girls with gaudily painted faces set amongst trashed painted canvases that inject possibility into an ordinary domestic setting.

If the arena of representational painting can provide a permissive ‘backdrop’ that allows the artist or viewer to conjure an imaginary scene, forms of abstraction can also operate as a cloak on reality in abstracted form, so as to transform perception of a given environment. The signature abstract patterns of Daniel Buren, Edward Krasinski or Yayoi Kusama variously operate so as to ‘claim’ the spaces and surfaces to which they are applied, and so alter our reading of them. In Buren’s case this has taken all manner of forms, whether by extending his familiar stripes to a string of flags hung from the gallery space across a street, on the sails of a flotilla of boats, or across the lawns of the formal gardens at Versailles. Kusama, likewise, has applied her hallucinogenic dot motif to all manner of surfaces and spaces, from her early performance work Flower Orgy (1968) in which naked participants were — with reference to the vernacular hippy practice of body painting popular in the U.S. at that time — daubed in red, yellow and blue dots of paint, and so semi-camouflaged within one of her environments, to her recent intervention wrapping trees in red-spotted fabric along London’s South Bank. The London-based artist Marc Camille Chaimowicz has, similarly, ‘detourned’ the expressionist or formal rules of abstract painting. Painting has formed the basis of his practice, in combination with performance works that he has appeared in, since the ’70s. From early on, Chaimowicz used his east end of London studio, embedded among David Bomberg- or Frank Auerbach-inspired painter neighbors, as a kind of interior design showroom in which walls, floors, fabrics and furniture were designed and decorated with the artist’s signature palette as a ‘set’ for his semi-fictionalized daily life, which was also recorded in film and slide pieces.

Distinct from the modernist notion that there is a ‘truthfulness’ to the medium, after Manet, these artists draw our attention back to painting’s capacity for disguise and trickery. In so doing, they not only open up new possibilities for the ‘dead’ medium, but stage rudimentary explorations of how we participate in the contemporary world via our reading and making of images. The Slovenian painting collective IRWIN, for example, took a political approach to the performative mise-en-scene in their 1984 exhibition “Back to the USA.” For this exhibition they recreated in paint an installation view of an American exhibition by the same name that was then touring Europe — one that was not, however, allowed to be shown in Communist Slovenia where they live. The works, by artists including Jonathan Borofsky and Matt Mullican, was deliberately painted by IRWIN as it had been seen by them in magazine reproduction form; contorted and skewed by the single-point perspective of the black-and-white photograph.

Lucy McKenzie or Paulina Olowska, more recently, draw attention to the old-fashioned idea of painting as a ‘window,’ and as illusion, by creating painted spaces that mimic the techniques of trompe l’oeil: whether in Olowska’s interventions in the grandly stuccoed rooms and marbled rooms at the Kunstverein Braunschweig, or McKenzie’s painted and free-standing ‘room within a room,’ inspired in part by the designs of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, part of the Arnolfini exhibition “Ten Years of Robotic Mayhem (Including Sublet)” in 2007. Such theatrical uses of painting are paired in both artists’ work with straight painting on canvas, on the one hand, and set in dialogue with constructed performance situations — such as Nova Popularna, a temporary bar-cum-exhibition in Warsaw in 2003 — in which they dress up and play upon models of ‘femininity,’ for example, as an extension of such possibilities. In Cologne in 2007, McKenzie also collaborated with two other artists to create an ‘interior design’ showroom that included ‘rugs’ painted directly onto the floor alongside her marbled walls.

The painted canvas, seen in this light, represents a complex space of negotiation between the immediacy of physical reality and its potential transformation: whether for the subject — who might ‘make up’ their appearance, or for the alteration of an environment via a painted mise-en-scene. Rather than registering the existence of its maker, the painted canvas might create a theatrical, fantastical, duplicitous “arena in which to act.” The combinations of painting and performance mentioned here are not concerned with the primacy of gesture and do not fetishize the handmade mark as an expression of subjectivity. Instead, they stage a variety of approaches to thinking through what painted pictures might enable; how their insertion into a situation might change it, or our participation in it; what are its poetic, and political, possibilities. Painting is considered by these artists in its applied form as a representational medium: a surface or screen that mediates between one’s inner vision and what is external or given. It is painting’s representational application rather than its mute facticity that create such productive, enchanted territory, especially from queer or feminist perspectives. As a primary form of writing reality as images, painting offers a parallel world that might be claimed as a space of inhabitation, or, perhaps, the capacity for intervention amid the expansive architectural fabric of the city. It is a constructed space that allows ‘realism’ to meet the performative construction of identity seamlessly, and, in this sense, knows no bounds for acting out, acting up.