After our first protest, PAIN faced a common critique: “If the Sacklers are too dirty for museums, who isn’t?”

We agree, but that’s no excuse for apathy — it’s a call to action.

Nan Goldin founded PAIN to confront the art world with the truth behind the Sackler family. Their multibillion-dollar fortune, used to fund museums around the world, was made off of addiction and death. Nearly five years later, the response from the art world is clear: we’ve propped up the Sackler family’s reputation as benevolent philanthropists for too long. With the help of artists and organizers across the globe, PAIN’s direct action campaign saw major victories over four short years. After public demonstrations at six museums — the Metropolitan, the Smithsonian, Harvard Art Museums, the Guggenheim, the Louvre, and the V&A Museum — each stopped taking Sackler donations, and all but one removed the Sackler name.

PAIN stands in solidarity with Harvard Medical School students and staff who continue to pressure their leadership into action. What doctor wants a medical degree from an institution bearing the Sackler name?

Despite Harvard’s reluctance, countless museums and universities have already purged the Sackler presence. The family is now infamous for their reckless greed, and the Sackler name will forever be synonymous with the overdose crisis.

In 2019, just as museums began refusing Sackler funding, reports out of London detailed Serpentine Galleries CEO Yana Peel’s indirect ownership of NSO Group, a cyberweapons company known for Pegasus spyware. After weeks of public scrutiny, Peel stepped down as CEO.

Next, activists in New York took the fight to the Whitney Museum, where Decolonize This Place organized nine consecutive weeks of protest against trustee and tear gas manufacturer Warren Kanders. Eight artists responded by pulling their work from the biennial, prompting Kanders to resign from the board.

Last year, MoMA chairman Leon Black was found to have had an extensive business relationship with the late sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. After repeated protests, more than 150 artists signed a statement calling for Black’s removal. He was gone less than two months later.

Not long ago, such a massive shift in attitude over big money donors seemed impossible. Given this momentum: Who’s next? When we refuse to be complicit in the reputation laundering of billionaires, we expose their crimes and clarify their position as our adversaries. These donors have nothing to give us that they have not already taken away — their charity is stolen, their art and artifacts are stolen.

Protests against these philanthropists co-opt their big budget renovations, turning delusional attempts to rebrand against them. Koch Plaza, built in honor of the late oil tycoon, becomes a streetside venue to both condemn his actions and combat the climate change denial funded by the fossil fuel industry. Each billionaire has given us an expensive backdrop for our protests against their corporate empire — and, luckily enough, each has their name written all over it.

In 1989, David Wojnarowicz wrote an incisive text included in the exhibition catalogue for “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing.” Titled “Post Cards from America: X-Rays from Hell,” Wojnarowicz’s piece attacked politicians ruthlessly blocking public AIDS education and treatment. Fearing conservative backlash, the National Endowment for the Arts defunded “Witnesses,” but once the resulting controversy attracted press and lifted the exhibition into the national conversation, David had this to say:

In the last twenty years, images and words that artists or writers make have had absolutely no power — given that we’re essentially competing against the media in order to create something that reverberates in images and words. And the fact that if, at this point in time, images and words that can be made by an individual have such power to create this storm of controversy, isn’t that great? It means the control of information has a crack in its wall.

While armies of lawyers and publicists typically dictate the media narrative on behalf of the rich and powerful, interrogating our institutions’ ethical standards through art and direct action creates a new battleground. A proxy court of public opinion, where artists can leverage their stature and push museums to make unprecedented decisions with massive ramifications.

PAIN’s protests channeled our collective grief and turned it into focused rage, permanently altering the discourse around toxic philanthropy. However, shaming the Sacklers is our method, not our goal — ousting billionaires from museums will not fix the problems billionaires create. Instead of “who’s next?” perhaps we should ask “what’s next?”

Ultimately, PAIN seeks to destigmatize drugs and dismantle the structural oppression faced by people who use them. In the United States, the forces of Big Pharma and the racist War on Drugs compound within a system prioritizing profits while incarcerating millions.

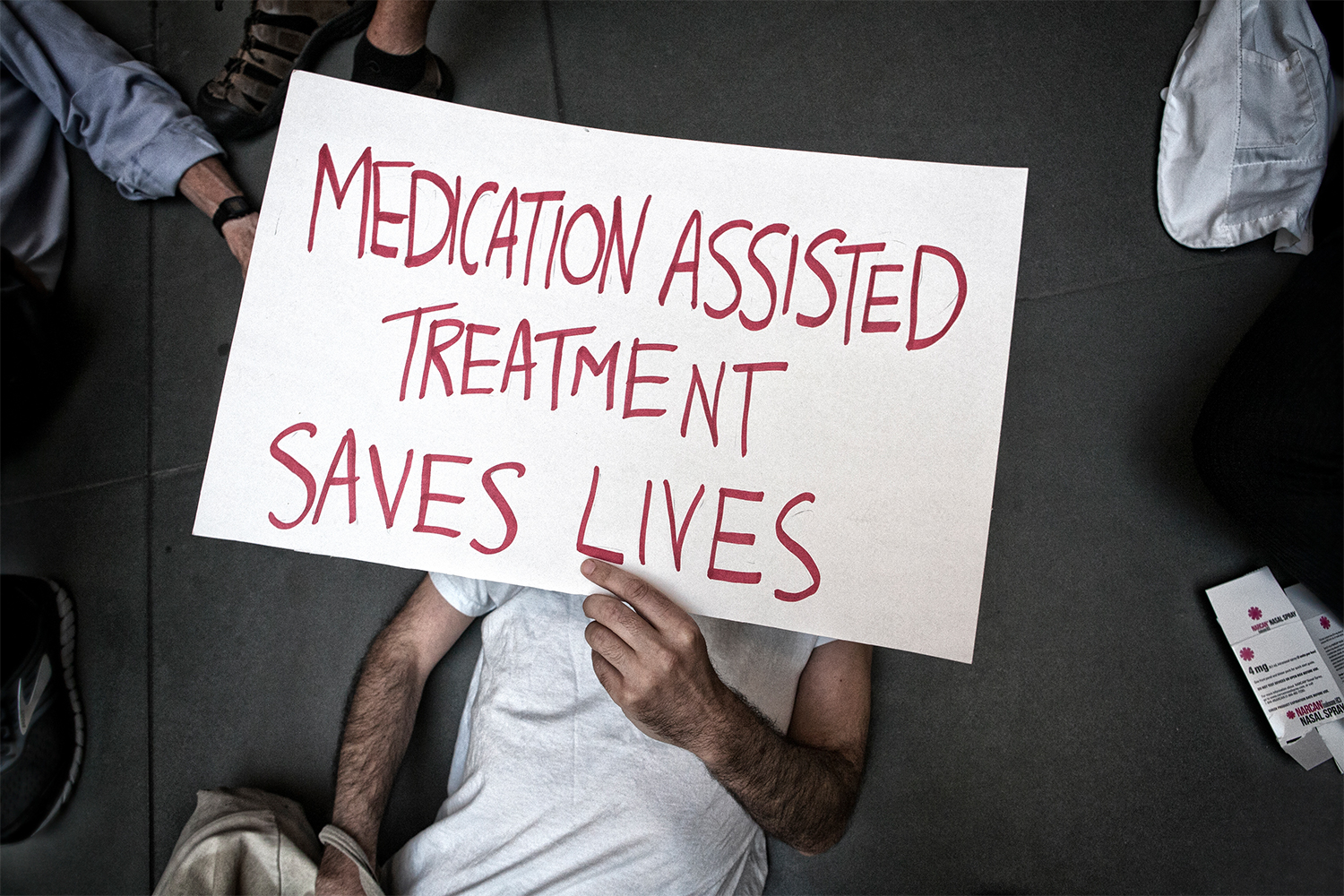

PAIN advocates for the expansion of public health measures based on the principles of harm reduction. This includes the distribution of overdose reversal drugs like naloxone, increased access to medication-assisted treatments like methadone and buprenorphine, and the unequivocal decriminalization of all drugs. Portugal has proven the success of this approach, passing drug decriminalization laws in 2001 that have since reduced overdose death rates by nearly eighty percent.

In the US, decades of prohibition have resulted in an unpredictable street drug supply, and the vast majority of overdoses are now caused by illicit fentanyl poisoning. This forces people who use opioids to choose between excruciating withdrawal and possible death on a daily basis. The global movement for safe supply programs, drug testing, and overdose prevention centers show how access to these vital services can radically improve the healthcare landscape for people who use

drugs.

We urge artists to find their fight. Cultural institutions are saturated by a variety of toxic, philanthropic sources. While daunting, this ubiquity also provides endless opportunities for solidarity. So maybe “who’s next? and “what’s next?” are the same question.

Our victories are cumulative, no matter how disparate. If we continue naming names, we continue building power. Whoever we struggle against, we must use our position as artists to tear open the void and show others the way out.

– New York, November 2022