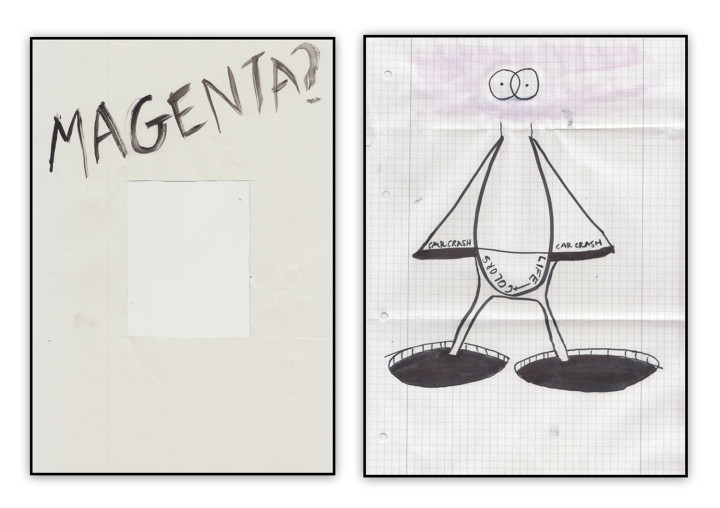

Google Magenta is a new artificial intelligence initiative by Google designed to answer the question, “Can we use machine learning to create compelling art and music? If so, how? If not, why not?” When it launched at the Moogfest technology festival in Durham, NC, earlier this year, Douglas Eck, the researcher in charge of the program, demoed a short piece of music generated by feeding a few notes into Magenta and letting it produce the rest of the song itself. Visual art is also in the pipeline; they say future iterations of Magenta could behave as collaborators to human artists, taking in their inputs and spitting out unforeseen alternatives. I tweeted at Eck to find out how Magenta got its name, and he wrote back: “I chose it. ‘Magenta’ worked as an acronym for ‘Music and Art Generation’ yet was also vaguely art related (color).”

Among communication brands, magenta is better known as part of the T-Mobile identity. In 2014, T-Mobile successfully sued Aio, a subsidiary of AT&T, for using a color they saw as too similar to their trademarked magenta in retail stores and campaigns. Part of the problem was classification, or how to name the color: many sane people might have called the color Aio was using “plum.” The Verge reported an Aio spokesperson firing back that T-Mobile needed an “art lesson” because “Aio doesn’t do magenta.” Post-controversy, magenta was expanded from a visual to a textual element of the T-Mobile brand, as the name for what they call “the coolest place” in the T-Mobile online customer support community. “The Lounge is all off topic, all the time. […] In the Magenta Lounge, we love sports, tech, gaming, and whatever you’re into. Keep it clean, make some friends, and please tip your wait staff,” reads the official T-Mobile site.

My interest in the color magenta began in 2014, when I was diagnosed with a magenta aura by Ari, an energy healer and executive coach I met during a research project I was doing with Columbia University School of Architecture on the topic of energy as a cultural issue (instead of just an environmental one). I was tapped for the project after the person running it saw a lecture of mine called “What’s the Energy of your Energy Drink?” — a talk I’d repurposed from a failed pitch to Pepsi, which I’d worked on as a trend forecaster at Wolff Olins, a global branding agency. My best friend, Rachel, who also worked for the agency, had gotten an aura reading from Ari and recommended I go see her too.

Rachel’s first session with Ari sounded a little weird. They met in Ari’s shared office on the eleventh floor of a commercial building in New York’s Garment District, above a wholesale specialty spandex store and down the hall from a Korean eyelash extension spa, where on two occasions I’d had hundreds of individual mink fibers glued to the tips of my eyelashes, one by one.

Rachel had her back against a white wall, while Ari (a middle-aged Jewish lady from New Jersey) was across from her, avoiding eye contact. The initial read was totally off, Rachel reported. “Are you obsessed with the future?” Ari kept asking her. “Are you paranoid?” As they worked through Rachel’s confusion, Ari determined that she was actually a crystal aura — a rare breed that takes on the energy of their environment almost automatically. That day, Rachel’s aura had been imprinted by a futurist she’d been brainstorming with just before she came to visit Ari. This guy lived alone in Vermont because his vision of the future was so clear and harrowing he couldn’t bear to be around other people. But he came into the city once in awhile to make money at the agency. Rachel had dragged his panicked aura with her, thirty blocks uptown.

My meeting with Ari began with a similar slippage. It seemed at first that Ari was having a difficult time taking my picture. She explained that she needed to unfocus her eyes — a form of attentional decontrol — and then we just sat there, suspended. Getting your aura read is a little like sitting for a long-exposure photo.

Ari seemed nervous and skeptical, then began interrogating me about my work history. As I described the anxiety I had about turning my art collective into a business, she started to exhale.

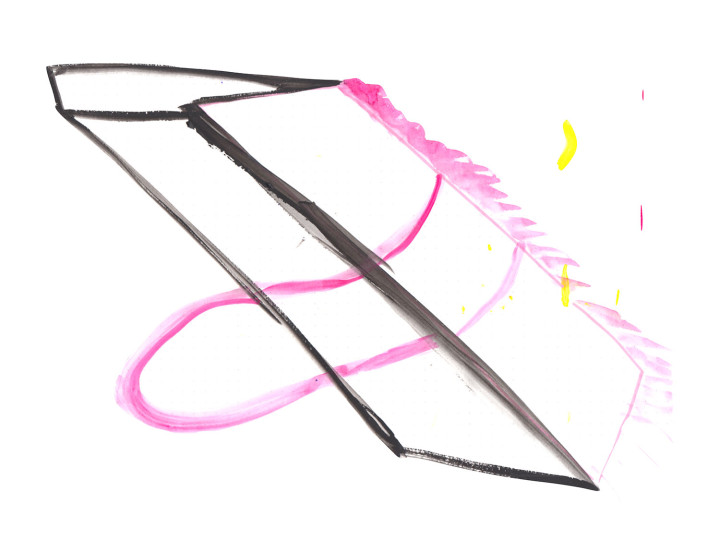

My aura had been in drag, she explained. I was manifesting blue (caretaker), green (business) and violet (cult leader), but they were fake: artificial, or more like instrumental, my costume for getting along with humans. My real aura was magenta, with a cone of white coming down into my head like a coffee filter, showing a direct and presently ongoing download of spiritual information.

Ari attributed my trend forecasting and “interest in the avant-garde” to the high frequency of the magenta light wave, which vibes faster than other human forms. She explained my kind as emissaries from another planet, sent to do reconnaissance on Earth and transmit high-level spiritual technologies. Magentas were simply ahead of the curve. As a result of this, they often felt alienated from normal people’s behavior: they were morally beyond good and evil, trying to pick up on the patterns of regular people without knowing how to buy into the systems that got them there in the first place. In this sense, being magenta was not unlike machine learning.

Ari attributed my trend forecasting and “interest in the avant-garde” to the high frequency of the magenta light wave, which vibes faster than other human forms. She explained my kind as emissaries from another planet, sent to do reconnaissance on Earth and transmit high-level spiritual technologies. Magentas were simply ahead of the curve. As a result of this, they often felt alienated from normal people’s behavior: they were morally beyond good and evil, trying to pick up on the patterns of regular people without knowing how to buy into the systems that got them there in the first place. In this sense, being magenta was not unlike machine learning.

Fashion is an important conduit for a magenta, which made Ari worried: she saw my alien spirit manifest in my manicure but nowhere else in my nothingville, pre-depressive-episode look. “A lot of magentas still have magenta hair,” she added, mysteriously. “You can see them around in Greenwich Village.” I found this insane, then remembered that I had dyed the ends of my hair bright pink only six months earlier.

I think Ari’s emphasis on my alienation was supposed to make me feel better: it was nature (not nurture); it was a byproduct of my talents (to vibrate faster than other people, to download info, to transmit). But it was not the right thing for me to hear at that particular time. I was on the waterslide down to a nadir, rolling slowly down a sine curve to my worst depression ever; meeting Ari was, in some form of retrospect, the kicker.

In the days following our meeting, I tried to learn about magenta auras (on Google), but something about the query was resisting me. Unlike astrology, which shows up on the Internet in a wide range of forms from spam to theory, aura information was exclusively janky and scarce. I kept grinding up on the search engine to little avail.

It occurred to me that maybe it was the visual nature of auras themselves that caused this unsearchability: a visual medium that resisted textual search.

I turned my attention to the color magenta itself.

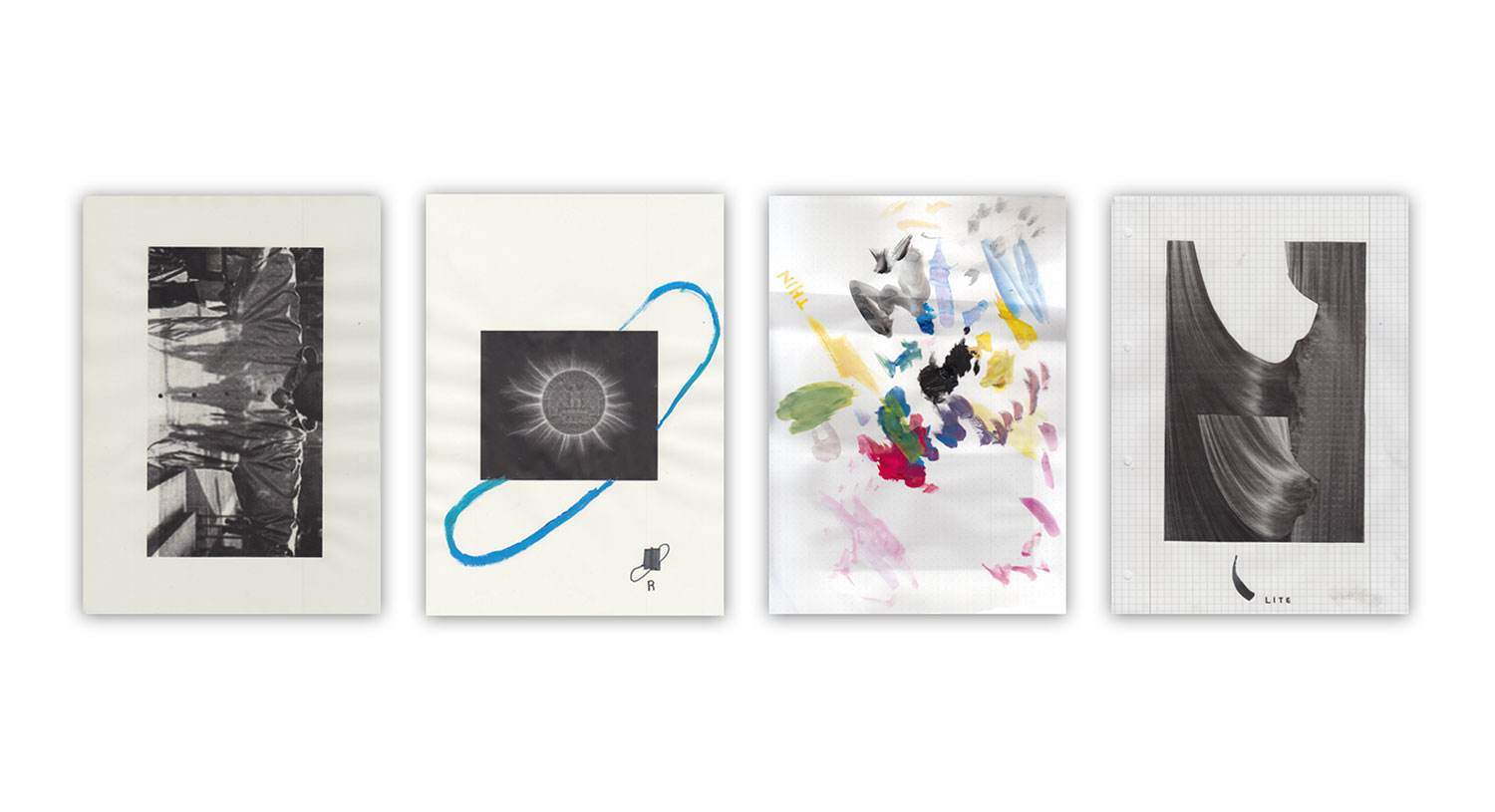

I had been wondering how one color (magenta) out of many (a spectrum) could be extraterrestrial, when after all it was just another color among the rest. It turned out this wasn’t quite true. Magenta was extraspectral: what some people call an “impossible color.”

As initially described in Goethe’s Theory of Colors, a certain color occurs when the two ends of the visible spectrum (red and violet) are overlapped at full intensity over black, forming a circle. Since this crossover wasn’t included in the traditional Newtonian rainbow, Goethe ascribed it a special power: the ability to bridge the physical and spiritual realms. It was a little like the late induction of Pluto into astrology: magenta was both of the spectrum and beyond it.

Somewhat parallel to the T-Mobile vs. Aio situation, the translation of the color we now call magenta has proven to be a problem in the interpretation of Goethe’s theory.

The word Purpur, which people think is Goethe’s magenta, was translated in the original edition by Charles Eastlake as “red,” “pure red,” or “bright red,” depending on how he felt. Yet Goethe equates this supposedly red color with the shade of a Roman cardinal’s robes and the color extracted from the shellfish dye murex.

Neither of these strike me as exactly magenta, but there’s an interesting connection here. The purplish dye that comes from murex is imperial purple, called porphyra in Greek and purpura in Latin, and it was the original luxury brand — first used by the Phoenicians.

Garments dyed with murex were said to get brighter with weathering and sunlight, instead of fading, and the dye became extremely expensive. In later Roman and Byzantine traditions, the color was restricted for imperial use only, eventually coming to stand for the ultimate class signifier: a child born to a reigning emperor was said to be porphyrogenitos, “born in the purple.”

I found a more aggressive reading of magenta in a recent essay from the Journal of Garden Studies called “Color in the Garden: ‘Malignant Magenta’” [Susan W. Lanman, Journal of Garden Studies, no. 2, Winter 2000, pp. 209–21].

I found a more aggressive reading of magenta in a recent essay from the Journal of Garden Studies called “Color in the Garden: ‘Malignant Magenta’” [Susan W. Lanman, Journal of Garden Studies, no. 2, Winter 2000, pp. 209–21].

The essay describes what happened after the discovery of magenta dye in 1859, when it was synthesized as an aniline red oxidized with stannic chloride by August Wilhelm von Hofmann at the Royal College of Chemistry in London.

The commercial colors of the late nineteenth century were a direct result of coal production: gas manufacturing created coal tar, a form of waste that yielded the benzol necessary to make aniline dyes like magenta. Another byproduct of the dye-synthesizing process was a compound called London Purple: a toxic insecticide that quickly went into widespread use. Coal created magenta; magenta created London Purple; and London Purple killed a bunch of flowers.

To certain garden theorists, the appearance of reddish-purplish flowers represented the encroachment of the industrial era into the theoretically pure space of the garden. Gertrude Jekyll, an artist and gardener who could be considered part of the Arts and Crafts movement, and whose writings on the garden were massively influential, dubbed it “malignant magenta” — not merely vulgar, but cancerous. She was likely following the color-logic of John Ruskin, who was an admirer of her paintings. To Ruskin, the extreme pollution brought on by the industrial processes that created magenta had aesthetic effects that were spiritual in nature.

Ruskin’s magenta was like the inverse of Purpur. “And now I come to the most important sign of the plague-wind and the plague-cloud,” Ruskin wrote of the polluted air covering England, “that in bringing on their peculiar darkness, they blanch the sun instead of reddening it.” [E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), The Library Edition of the Complete Works of John Ruskin, “Vol. V: Modern Painters” (London: George Allen, 1903–12) pp. 38–39.]

Magenta stood for a deadened version of the scarlet he praised as the most powerful color, the shade of blood and life force. Magenta was scarlet, but with the smog filter of commerce: scarlet viewed through a filter of death.

Magenta stood for a deadened version of the scarlet he praised as the most powerful color, the shade of blood and life force. Magenta was scarlet, but with the smog filter of commerce: scarlet viewed through a filter of death.

In What Color Is the Sacred, the anthropologist Michael Taussig frames the same spiritual effect a little more broadly:

“Thanks to their ability to mimic nature, the new industries of the famed Industrial Revolution, and most especially of the chemical industry, promised us utopias and fairylands beyond our wildest dreams. As the spirit of the gift, color is what sold and continues to sell modernity. As the gift that gives the commodity aura, color is magical and poisonous.” [The University of Chicago Press, 2009, p. 25]

I would argue that magenta, more than any other color, captures the problem of the spectrum’s complicity with capital. As a color, magenta identifies the internal oppositions of a creative personality, and resolves, however temporarily, its undefinability. This may be one reason it has not yet expired for me as an interest of my identity. As I go around and meet people, as I go about my business, I do pattern recognition for magentas. I try to find speed, fervor, faltering, dye jobs, manners of vibration. I’ve figured out this much: many artists and many startup founders — maybe the figure of the fraught young entrepreneur in general — strike me as possibly magenta.

The other day, I brought up the question of magenta to my brother as we sat in our cousin’s apartment in Berlin, smoking weed and looking at a plant (called Wandering Jew) that is both purple and green at the same time. I wasn’t sure if we were seeing it the same way. My brother, who is color blind, told me most people don’t understand color blindness at all. He only sees colors after other people name them. For example, when my mother gave him a jacket for his birthday, he thought: what a nice maroon Muji jacket. But once everyone else said it was dark green, it became dark green for him, too. “I think my color blindness is a form of laziness,” he said. “I don’t put in the effort to see a color, then wait till someone names it for me. That’s a little reductive, but basically it. If you hadn’t said anything, I would have thought that plant was green, because plants are green. But now that you say it’s purple, I see it.”

Then he directed my attention to Google Magenta, suggesting it was the impossible, extraspectral quality of the color that Google was channeling with the name. He was wrong, but also probably right, in that magenta (big magenta, magenta as I’ve known it) keeps slipping out of context, bleeding into new identities and generating its own excess. As a brand, Google Magenta attempts to reverse engineer, and therefore reinvent, the motion of a creative mind. However indirectly, it has taken for its name a color that reflects the history of this problem.

Can machines make art? And if not, why not? Google Magenta is a brand that asks a question, not a brand that sells a product. For me, an artist and a brand consultant with a mostly magenta aura, the if not, why not part of the question is what I find most interesting.

So here’s one thing to keep in mind.

Beyond the hue of a luxury brand, beyond the vibration of colors through commodities, magenta suggests a completely new possibility: that an aura can, and already has, become a brand — all by itself.