I had planned to use the call to ask Nora Turato questions about typography — about the typefaces that she uses in her visual work. The call was postponed because she’d been tear-gassed in Paris. She hadn’t been actively protesting. She was standing at an open-air bar, decompressing after a performance at the Centre Pompidou, when chaos broke out in the street, glasses smashing and tables flipping. Everyone ran, but initially no one knew from what: a terrorist attack, riot police, a giant lizard? The realization that everyone in the running crowd was weeping arrived some seconds before the discovery of the cause of the tears and the smashed glass: a confrontation between police and an anti-labor reform protest taking place a street away. Just ordinary civil society tear gas. You might as well throw your drink away, because the acrid flavor of the gas gets into everything.

Is there anything more banal than protesting in Paris? Since the revolution helped bring the republic into being, protesting the French state is one of the rituals that constitutes the French state. The street protest lurches between festival, parade, and deadly earnest confrontation. It’s a kind of beauty contest for attracting the attention of government, that lazy leviathan. Attending one is a process of probing power, to work out where the state is most irritable, and also where its cognitive dissonance becomes most comic. The protest is also the space of the slogan, an Anglicization of the Gaelic sluagh-ghairm, or battle cry: the phrases that leap from protester to protester, that swing between collective chants and personal demands. That’s part of the joy of the mass protest: it is both a completely transgressive and completely communal experience, a little like making love. At least, all this is what our grandparents claimed for the 1960s.

Perhaps that picture is not true anymore. Things are weirder now. Relationships between cause and effect are more opaque. Disinformation has grown over everything, and so thick that it’s hard to see the outlines of the initial problem, let alone the coherence of details. The traditional treatment for washing tear gas out of the eyes is milk. During the BLM protests in summer, message boards ran hot with discussions about whether almond milk or oat milk made a better vegan substitute. Is this parody? Not exactly. Other people’s concerns are easy to mock, but it is important not to start and end with absurdity. Rather, what matters is the algebra of cognitive dissonance: the incoherence of the protester multiplied by the insanity of the state. And this controlled dissonance is ventriloquized in Nora Turato’s performances.

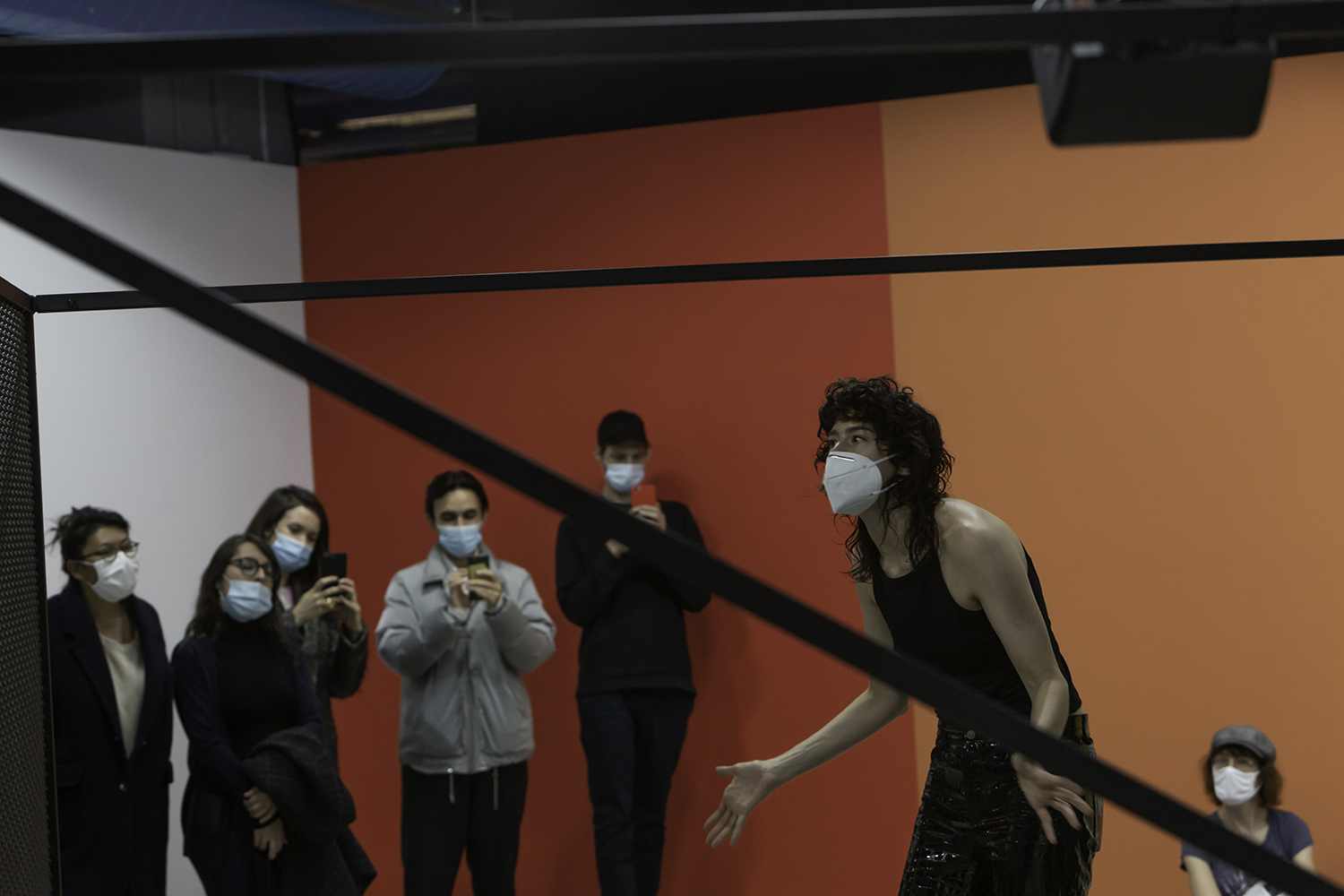

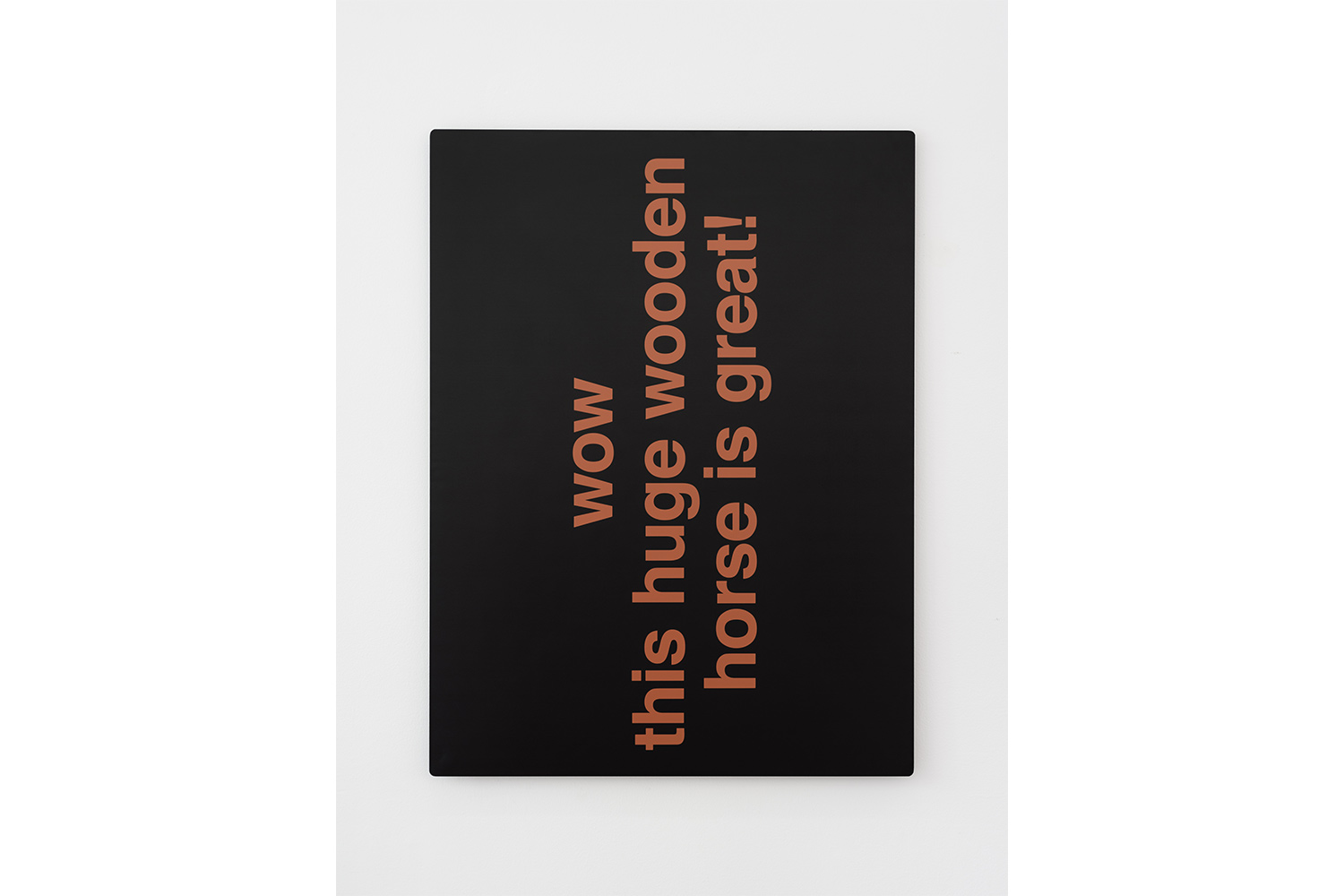

Nora Turato performs twenty-five-minute-long texts and makes pictures. In her most recent performance, presented under the excellent title wow this huge wooden horse is great!, she recited, from memory, a text of more than four thousand words. The text veered in format from lecture to cabaret, from fragmentary memes to song, and from intimate whispers to forceful obscenities. It was not so much a speech as a compilation of voices, a schizoid operetta. Some of the text is her own, some of it is citations, quotes, and appropriations, and sometimes it breaks stride mid sentence: as when she notes, quoting the fragmentary idiom of Facebook, “people you may know has upped its game.” It is almost impossible to determine where she stops and the muddy information streams of the world begin, but the ontology of this world can be summarized with one of her lines: “everything edible is made from corn, everything inedible made from petroleum.”

At the moment the internet is abounding with satires of the internet. There is an entire genre of meta-comedy that is devoted to being witty about the internet, the inanity of memes, the vapidity of influencers, the stupidity of commenters. The fine art of trolling sometimes embodies the stupidity, sometimes the wit, and at its best ambiguously slides the line that separates both. But this is not what Nora Turato does. Nora Turato is not presenting arch comedy that pokes fun at the internet. Rather, she ventriloquises the internet almost as if she is caught in a séance in which she failed to channel the dripping thoughts of a long-dead ancestor, but instead got the fire hose of her own generation. This is not a talk about the internet; this is the voice of the internet, a desublimation of symptoms, as much shamanism as critique.

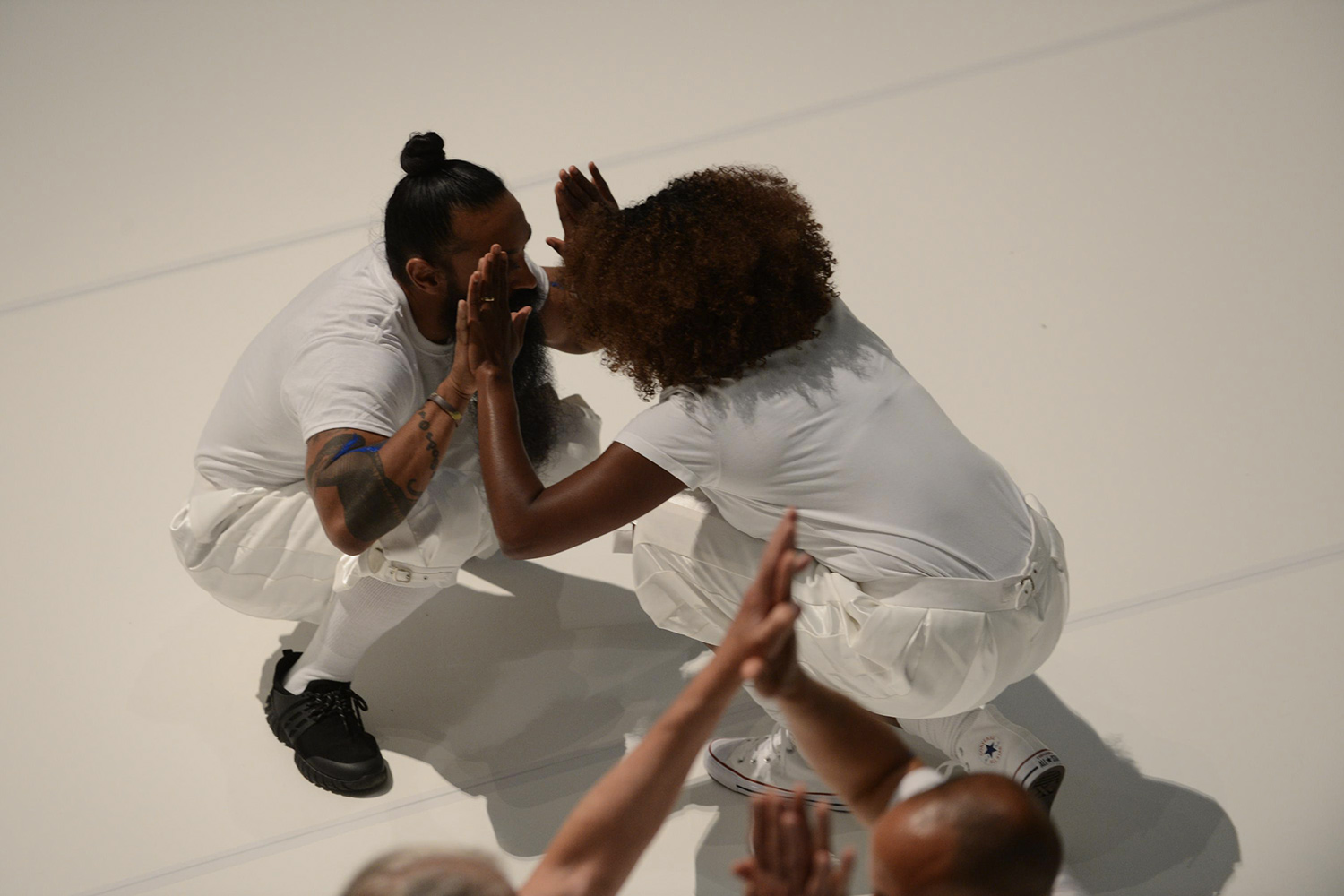

The language, at times, runs through her, as if she is being violently played by her own scripts. It is as if Nora Turato empties herself out in order to perform. For the genre she has inhabited, this makes sense. To construct a sensitive seismograph, you need to use the lightest needle possible, so that it transmits all the vibrations of the earth with the highest fidelity. Within Turato’s live performances, the constant percussion of citations is a kind of mosaic of blanks. Her texts shackle her, recalling the old psychoanalytic formula that language is an alien inhabiting our bodies. Sometimes, as she recites them, she appears to be accelerating and decelerating in the language, like an animal trying to wriggle free of collar and leash. The breaths and stresses don’t always appear when you expect them, nor do the songs clearly mark themselves off from the cussing. The mismatch between physicality and prose is carefully rehearsed. She records the texts that she writes, practices them, re-records them, until every seemingly spontaneous gesture is baked into the text.

The importance of tempo is visible in her videos, in which she “performs” her texts by projecting the sentences on a wall. Each sentence is projected for exactly as long as it takes her to read it out loud in a performance. Here speed is an animal constraint. Otherwise, the text is presented in a form that is stripped of anything aesthetic. It is almost, but not quite, reduced to information (but we will get to that in a moment). Only the turnover of the words betrays haste, betrays their biological and historical origins. Her process consists of an obsessively followed sequence of logical decisions that cumulate into something insane (and as she points out herself, that’s what mania is).

When Nora Turato does get reflective, she nails the disingenuity of our days with a few strokes:

these self-conscious times have

furnished us with a new fallacy

call it the reflexivity trap.

this is the implicit, and sometimes even explicit, idea that

professing awareness of a fault absolves you of that fault —

that lip service equals resistance.

the problem with such

signaling is that it rarely resolves the anxieties that

prompt it. mocking your emotions, or expressing shame

or doubt about your emotions, does not necessarily negate those emotions

castigating yourself for hypocrisy, cowardice, or racism

won’t necessarily make you less hypocritical, cowardly, or racist.

The reflexivity trap, the idea that advertising your faults constitutes absolution, is perhaps one of the strangest side effects of the entire inverted subjectivity of the internet, in which interior life is broadcast as “content” and productive life disappears into code. Nora Turato’s take on transectionality seems to be as a kind of nightmare, the flipside of algorithmic marketing models, in which the different identities that people cultivate online start falling into dissonance with each other. Far from being the harbinger of total liberation, our squabbling avatars have produced an internecine mess.

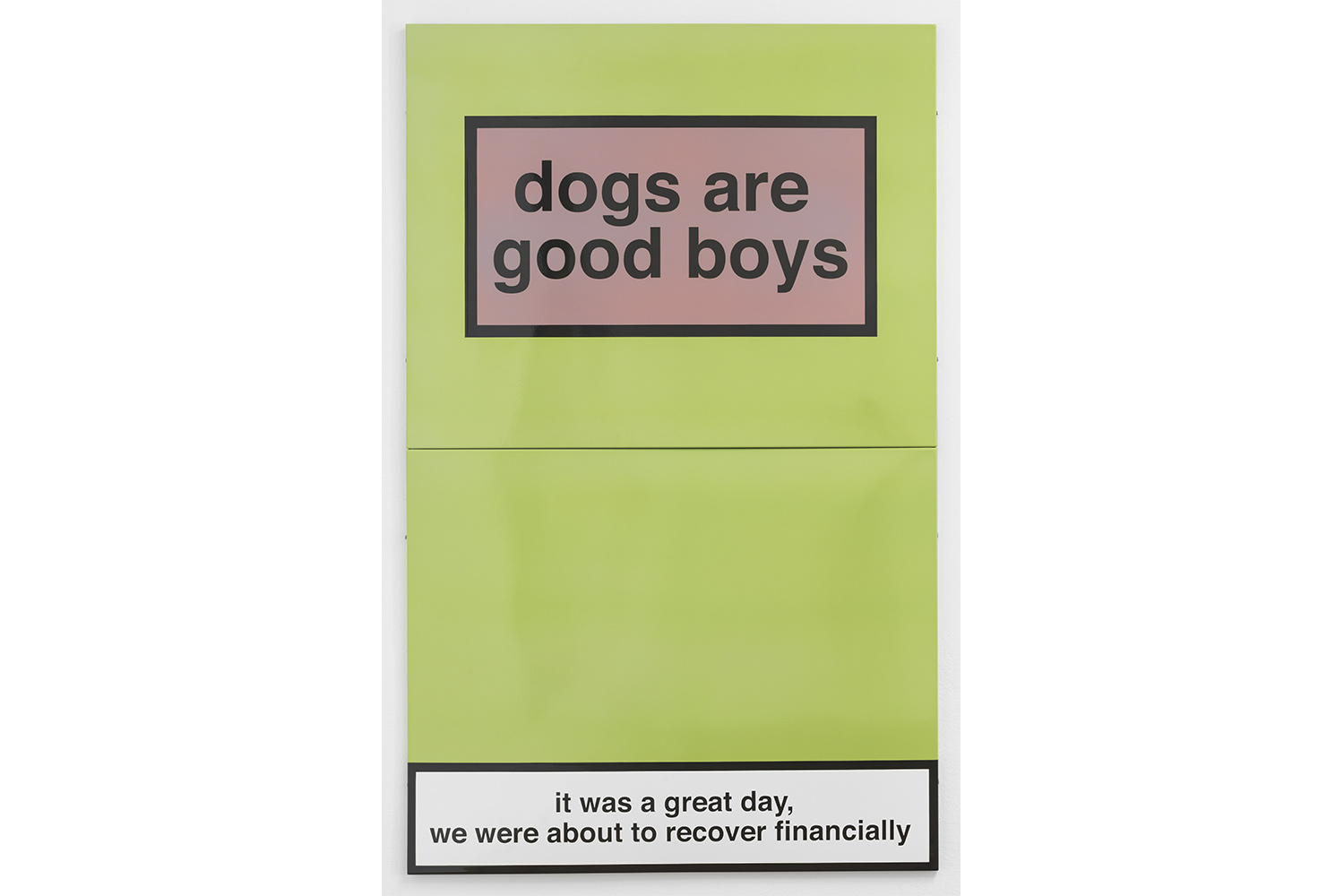

I had wanted, in the conversation, to ask her about the typefaces in her pictures. Nora Turato’s earlier works had explicitly played on the look of health warnings on cigarette packets. Those naked boxes, with their blank Helvetica text, that all over the world cover not less than a third of the packaging with clear slogans in whatever language the cigarettes are sold: Smoking kills; Roken is dodelijk; Pušači umiru mlađi. Those messages have a special charm for Nora. They recall that scene in the 1980s John Carpenter cult film They Live, in which the drifter puts on the magic sunglasses and sees the advertising around him turn into a san serif declaration of their own unencoded meaning: “Obey,” “Marry and Reproduce,” and so on. The thing about cigarette packages is that they become in some ways more attractive with their self-denunciatory messages. In accordance with the principles of the reflexivity trap, they announce everything awful about themselves, even as they continue to be poisonous. And this capacity to be evil and to tell the truth about it, and to survive nonetheless — what else is it but a kind of glamour?

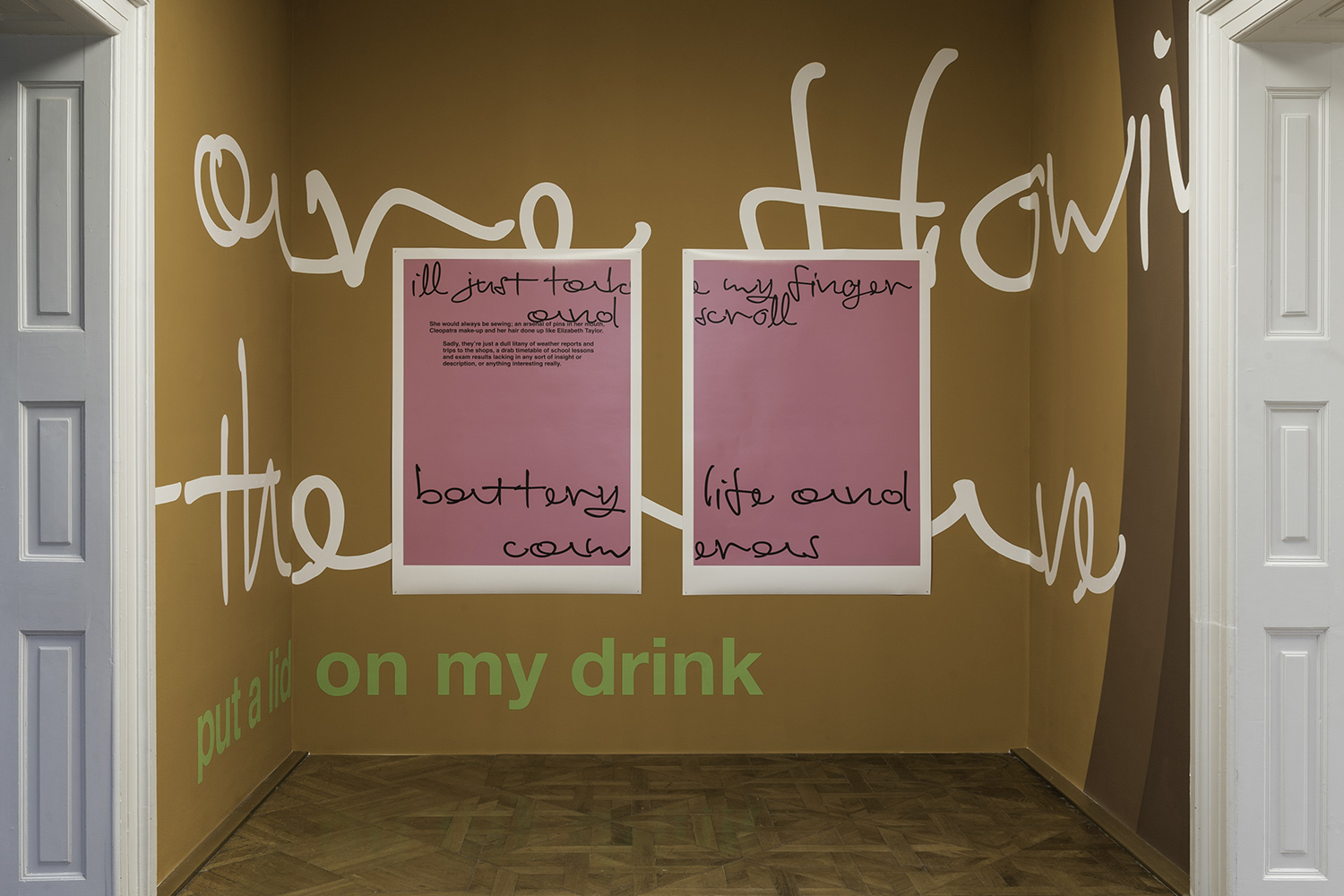

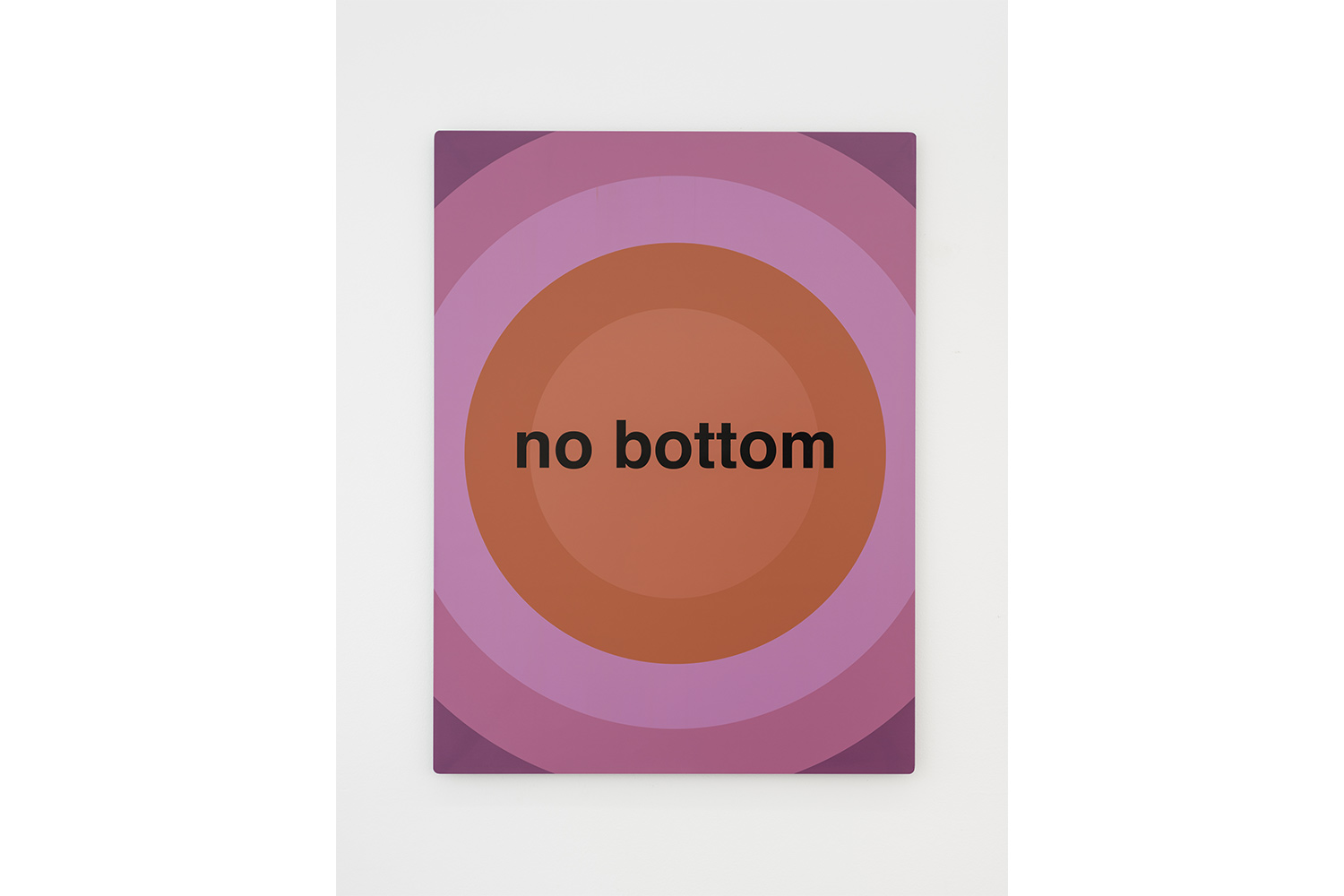

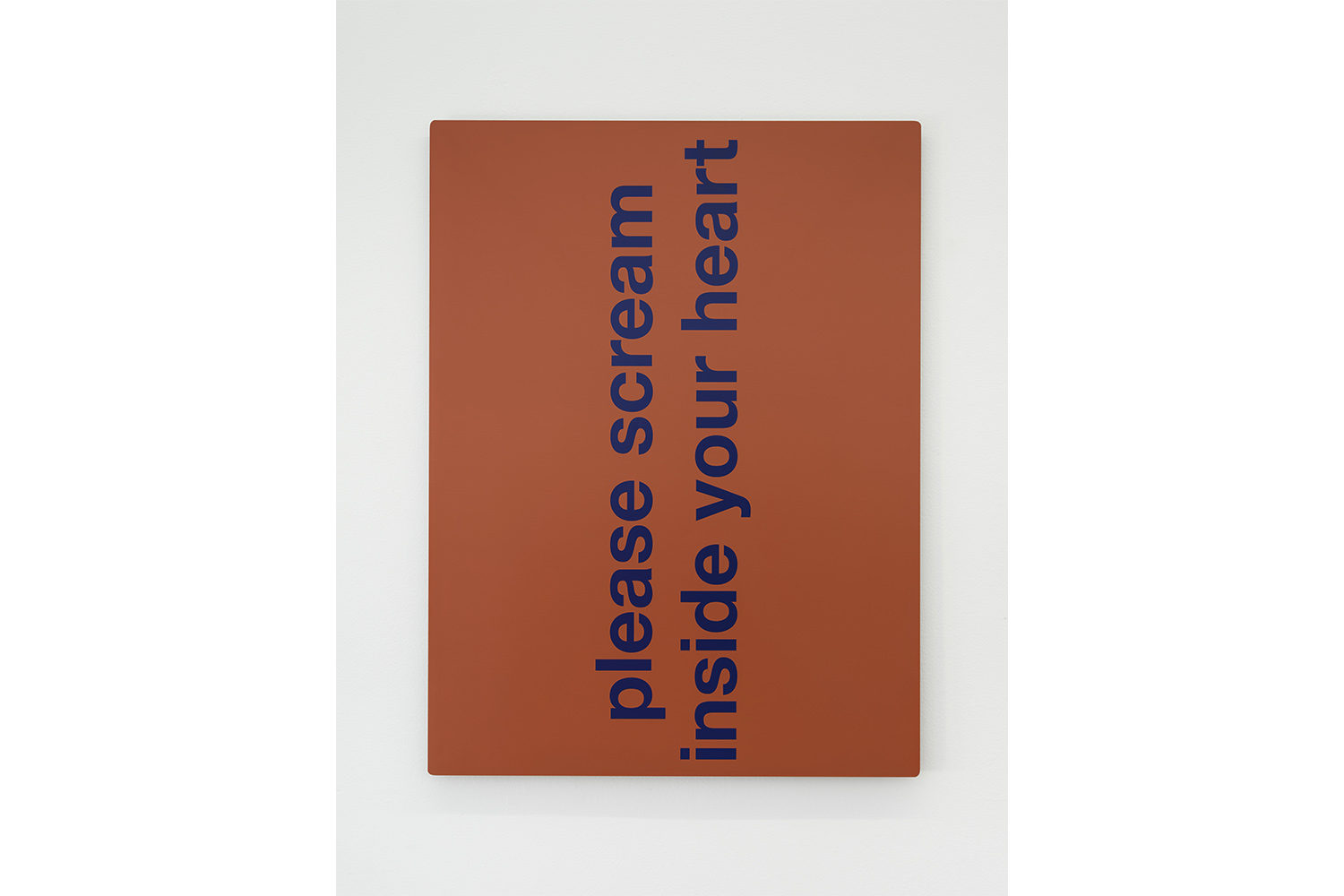

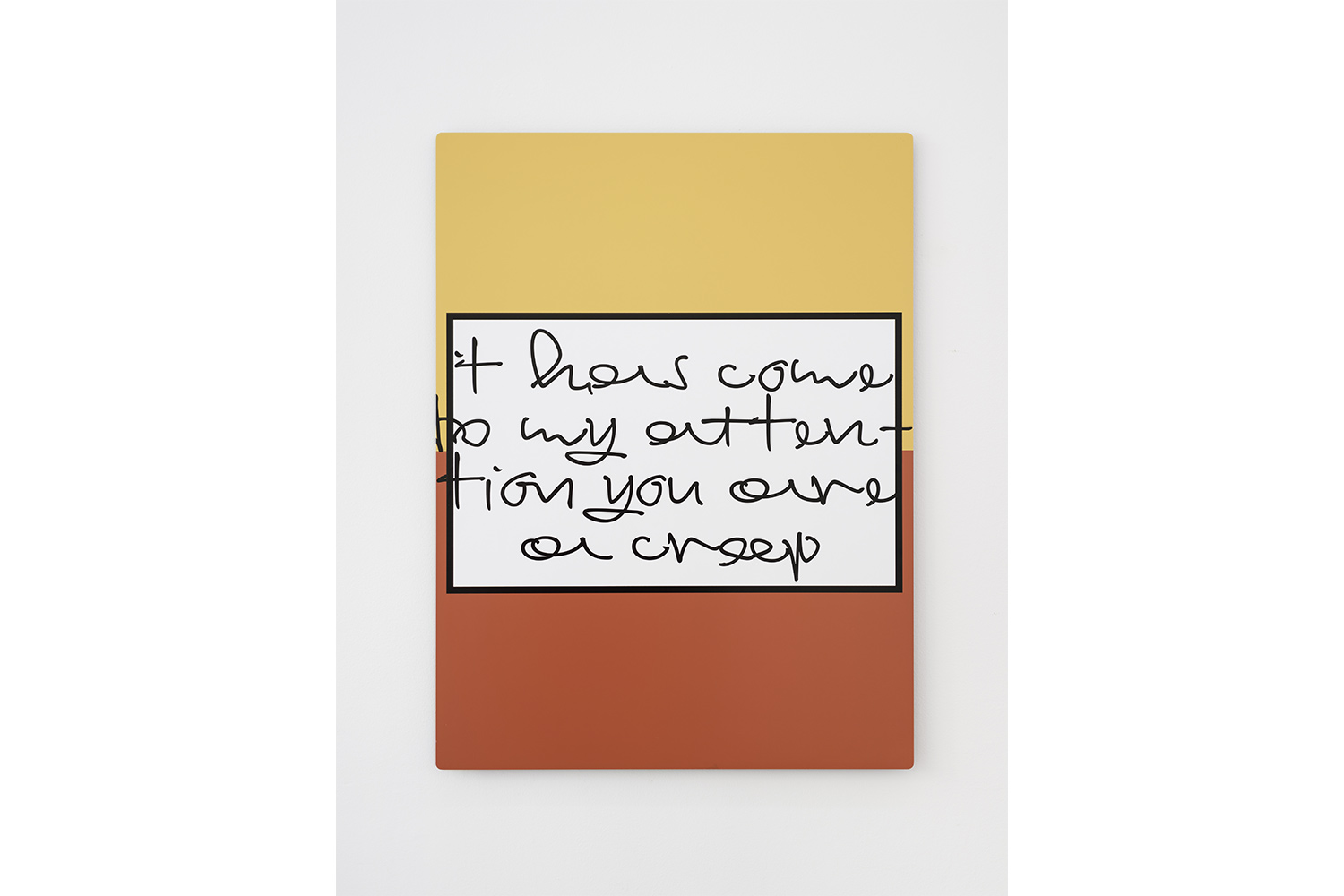

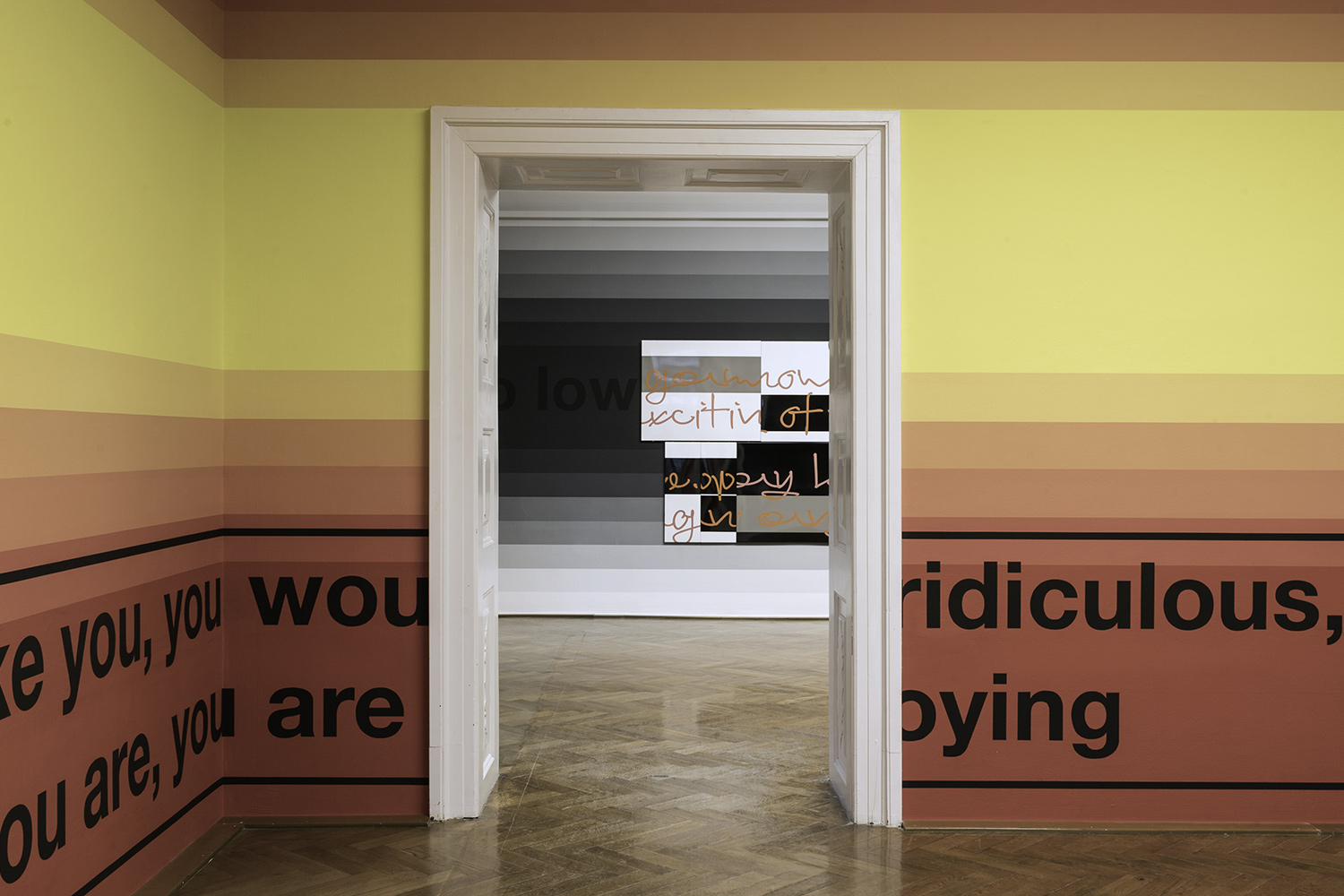

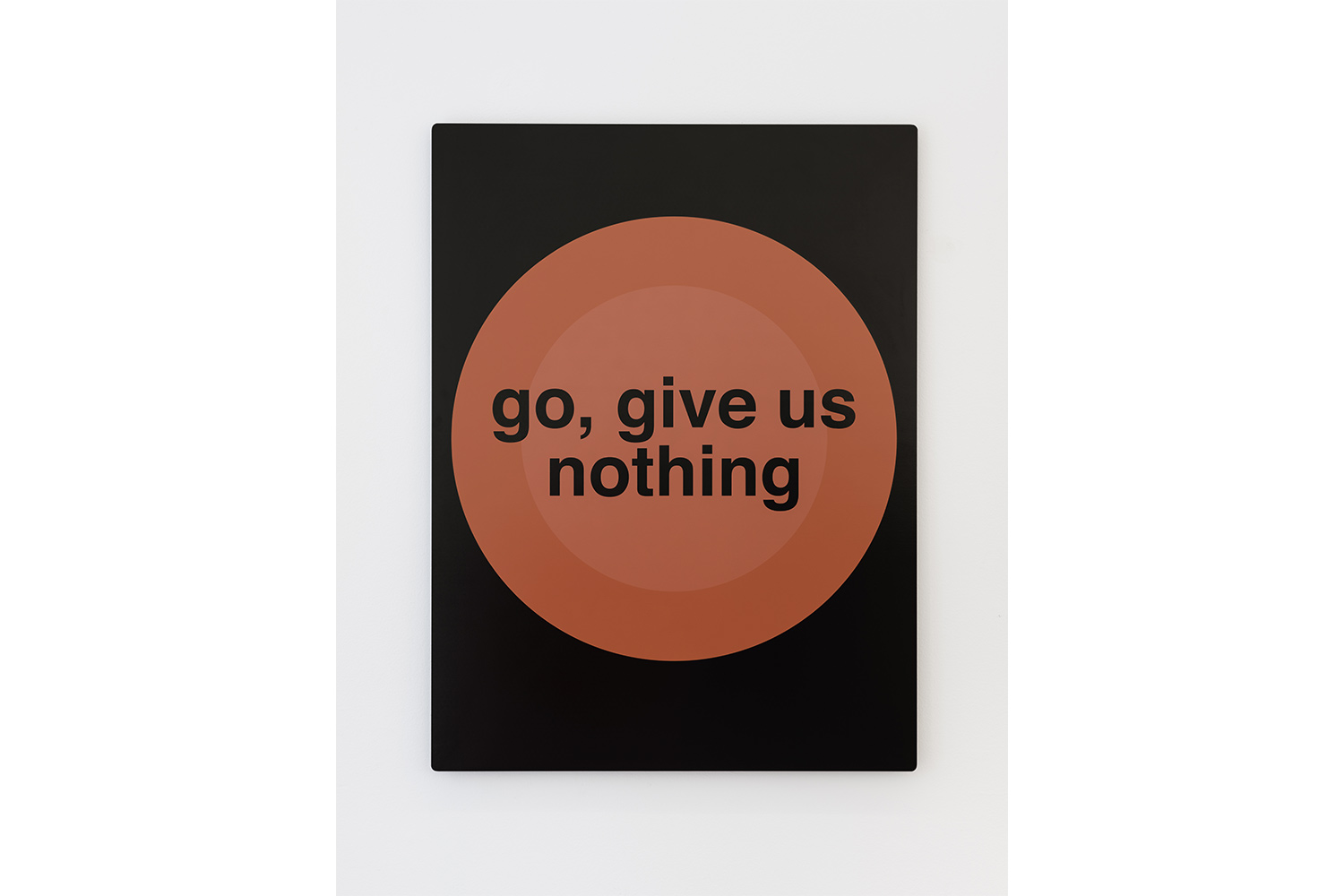

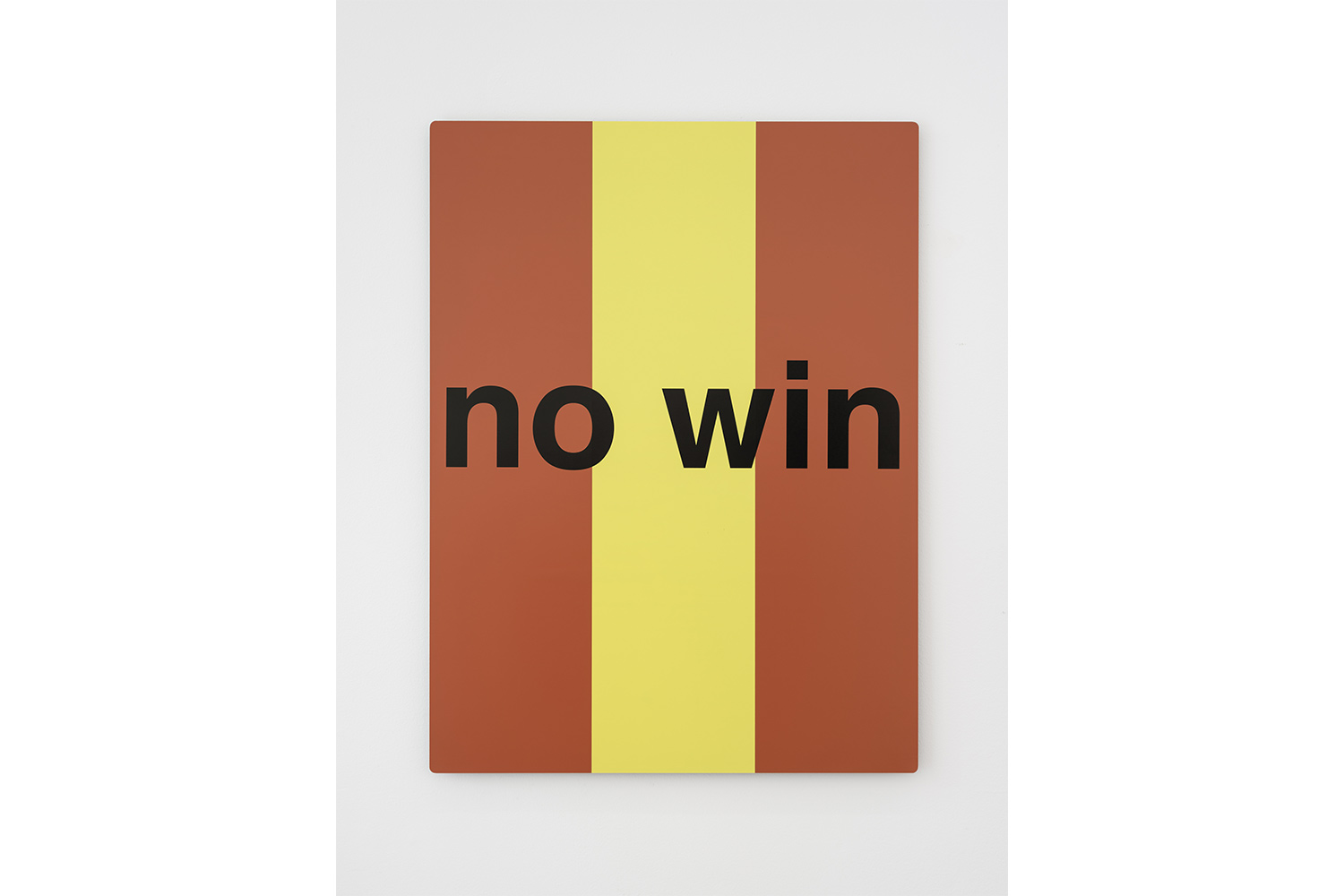

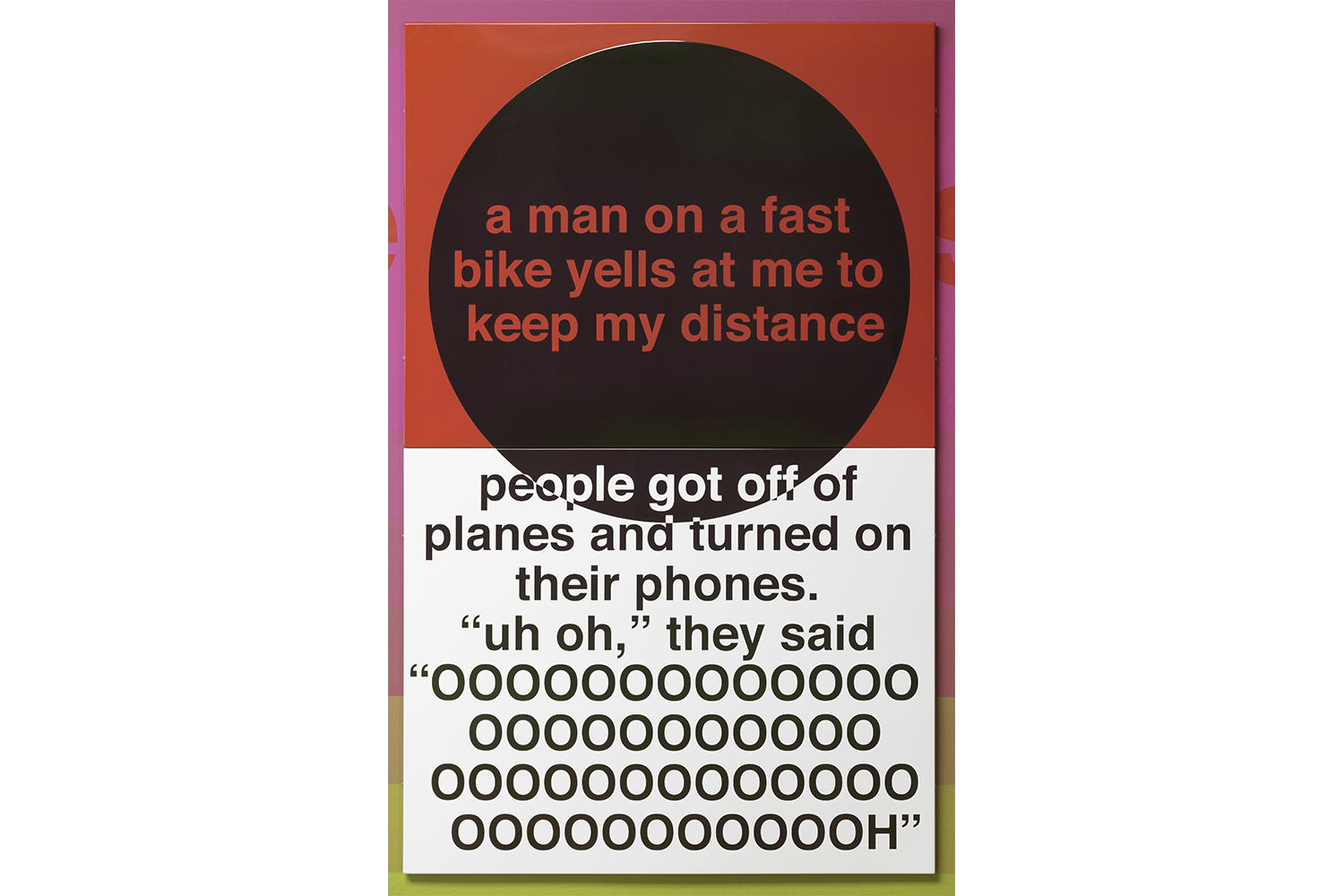

This brings us back to information. Nora Turato’s text works make a toy of it. They are phrases culled from her performance and presented in standard Helvetica on laminated sheet-metal plates that float a little out from the wall, like screens. “go, give us nothing,” says one laconic imperative. These phrases, shorn from their context, are no longer communicative. They barely belong to language. They are not signifiers, pieces of meaningful language that point to some state of affairs in the world. They break the standard relationship between text and image. They are not captions to absent images, nor are images desired to illustrate them. They are just words. Idioms with borders. The last time that words acquired this strange a relationship to image was in Foucault’s essay on Magritte and calligrams (“This is not a Pipe”), but that essay was about semiotic excess, and this is about semiotic deficiency. Looking at her work on the wall, I find myself in a gallery full of hieroglyphs. “it’s amazing you can type when you can’t even read,” she might reply.

the prevailing philosophy here today is kind of a positivism

that treats arriving at the truth a simple matter of data

collection: the more facts we have, the closer we are

to a complete picture of reality.

All of this is a long way to explain why Nora Turato is not ironic. Irony suggests condescension, the luxury of detachment. Rather, this is something closer to an assertion of defiance, even though we got the memo about resistance being futile. The leviathan in whose belly we are trapped is not hostile to our existence, but more oblivious to us than ever.

tell me who moves chaos?

chaos moves by itself sir

The chaos has many names: history, capitalism, power. None of them reveal anything of importance. But that doesn’t mean that we can just give up, or that we should stop protesting, even if we didn’t know that we were protesting when they gassed us. You don’t know why you are crying and running, but at a certain point, you remember that you put your good sneakers on this morning. Perhaps this is the reason for that. You keep running.