The current decade in Brazil began with a so-called new phenomenon: the artist group.

More than following an international tendency or a new urge toward sociability, the Brazilian artists’ initiatives united against the lack of active and innovative art spaces in tune with new art trends, responding to a sense that bureaucracies and market forces were not compatible with the questions raised by this generation. At the same time, we observed the first results of globalization in our art system. On one hand, art production started to gain more international attention and respect thanks to the efforts of gallerists and curators (in particular the work of Paulo Herkenhoff in the XXIV São Paulo Biennial) and the recognition of the importance of Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark. On the other hand, the decentralization of the capital, along with improved technology, led to an increase in the flux of information, which caused a redesign of the politics of museums and a need for more professionalism, most notably in the peripheral capital cities. Since the mid ’90s, we have seen the emergence and solidification of new points on the national art map, the renewal of museums of contemporary art and the founding of art galleries in cities such as Recife, Fortaleza, Salvador, Belém and Belo Horizonte.1 It is remarkable how the art scenes of these places took advantage of the confrontation between their local peculiarities and the global repertoire, burgeoning with this new influx of exhibitions, professionals and concepts generated by the institutional chain, not to mention the growth in visibility for the local art scene. It provoked serious renovation not only in art production but also in the emergence of new curators that have been recognized nationally.2 In five years, politically driven cultural policies started to share space and legitimacy with expertise in art and generated a more professional atmosphere, giving the opportunity for many art professionals to remain in their original cities without feeling obliged to immigrate to São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro. It is always worthwhile remembering that Brazil is a continent of diversity and co-existence of various temporalities to which the contemporary art field adds new layers of complexity.

As we approach the end of the decade, we can perceive that the Brazilian art system has matured. However, this affirmation needs to be contextualized. It does not mean that we have reached ideal institutional and financial stability (it is, after all, common for art institutions in developed countries to be able to plan their programs three or five years in advance, knowing that the required money and support will be available), but that we have achieved a new level of dialogue and consciousness regarding public and private policies towards the art field. In recent years we have witnessed the qualification of conditions offered by institutions to artists (both public and private — especially art centers run by banks) and the rise of new fellowships, funding and prizes for young artists, such as the Rumos Artes Visuais Itaú, the CNI SESI Marcantonio Vilaça Prize, the Museu de Arte da Pampulha Grant, the Salão de Artes de Pernambuco Grant and the Iberê Camargo Grant. Additionally, there are myriad art spaces that promote emergent art: Centro Cultural São Paulo, Centro Mariantonia (SP), Paço das Artes (SP), Funarte (RJ, SP and Brasilia), Fundação Joaquim Nabuco (PE), MAMAM no Pátio (PE), SESC, Galeria Marcantonio Vilaça (Instituto Cultural Banco Real, in Recife). Obsolete in major parts of the globe, the ‘salon’ of art is extremely popular in Brazil. These bring legitimacy and visibility, helping to facilitate the acquisition of works by museums and collections, especially by young artists not represented by art galleries and whose works do not otherwise sell easily. In South Brazil, for instance, each major city has its own regional salon that attracts mainly local artists. However, the main salons can offer up to R$20,000 (approximately $10,000 US) in prize money and receive almost 2,000 applications from all parts of continental Brazil.

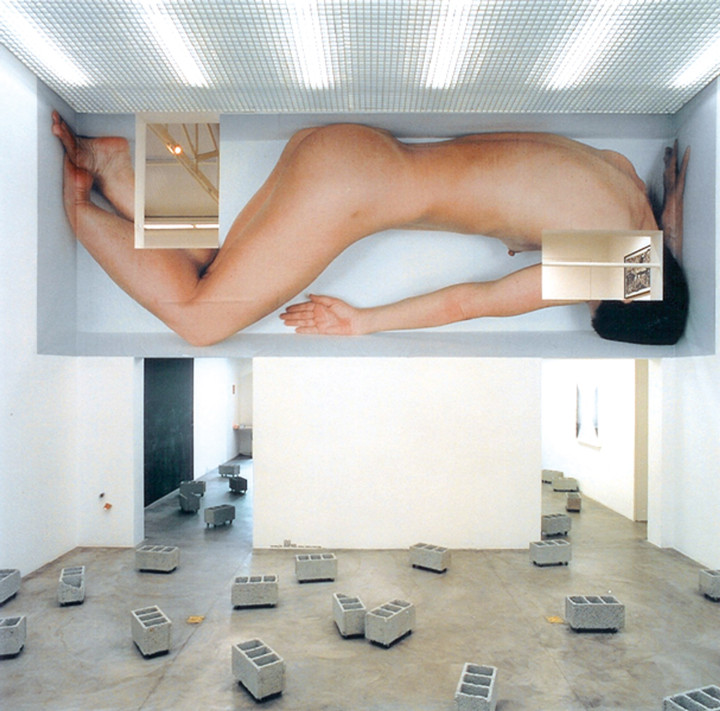

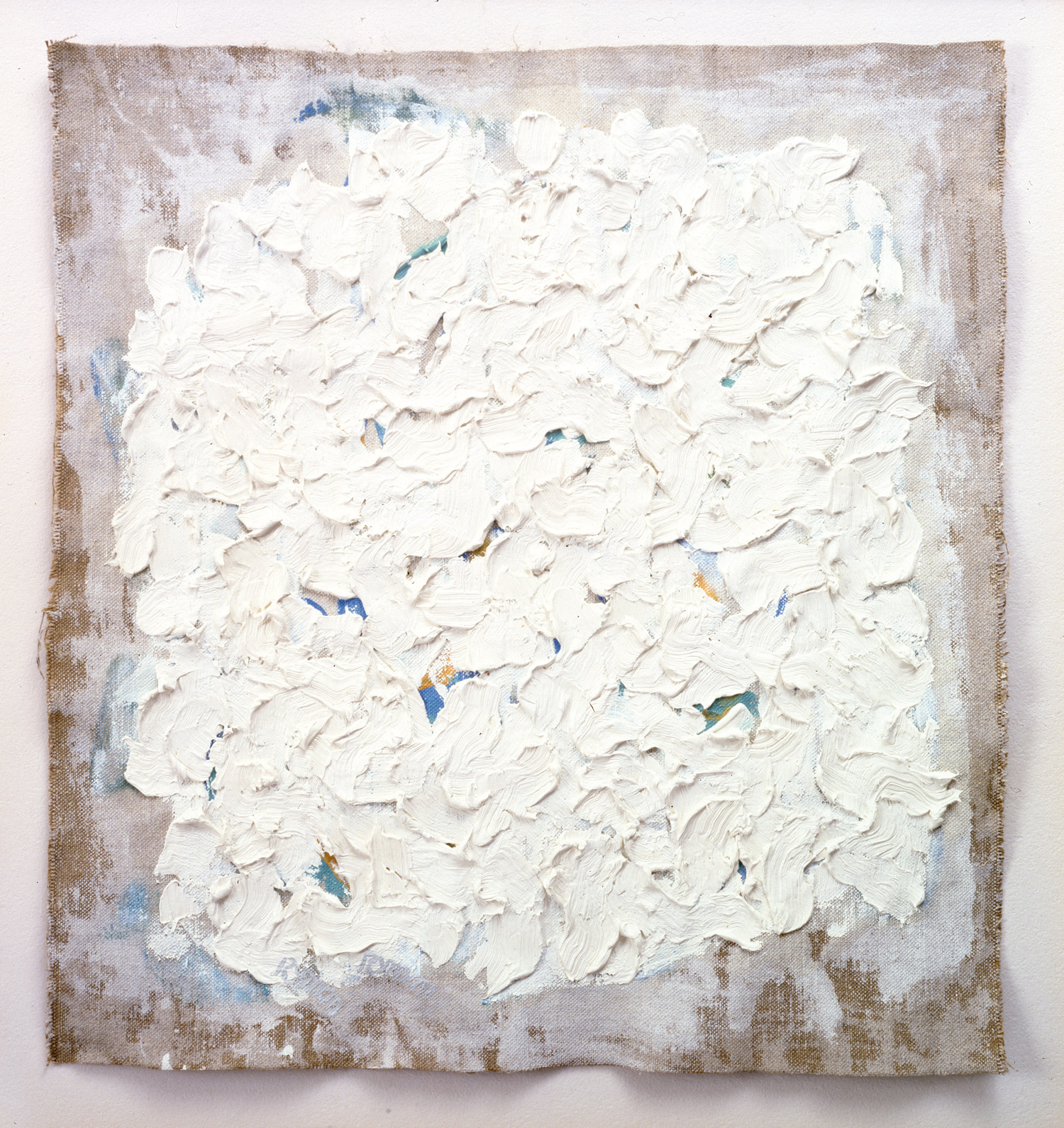

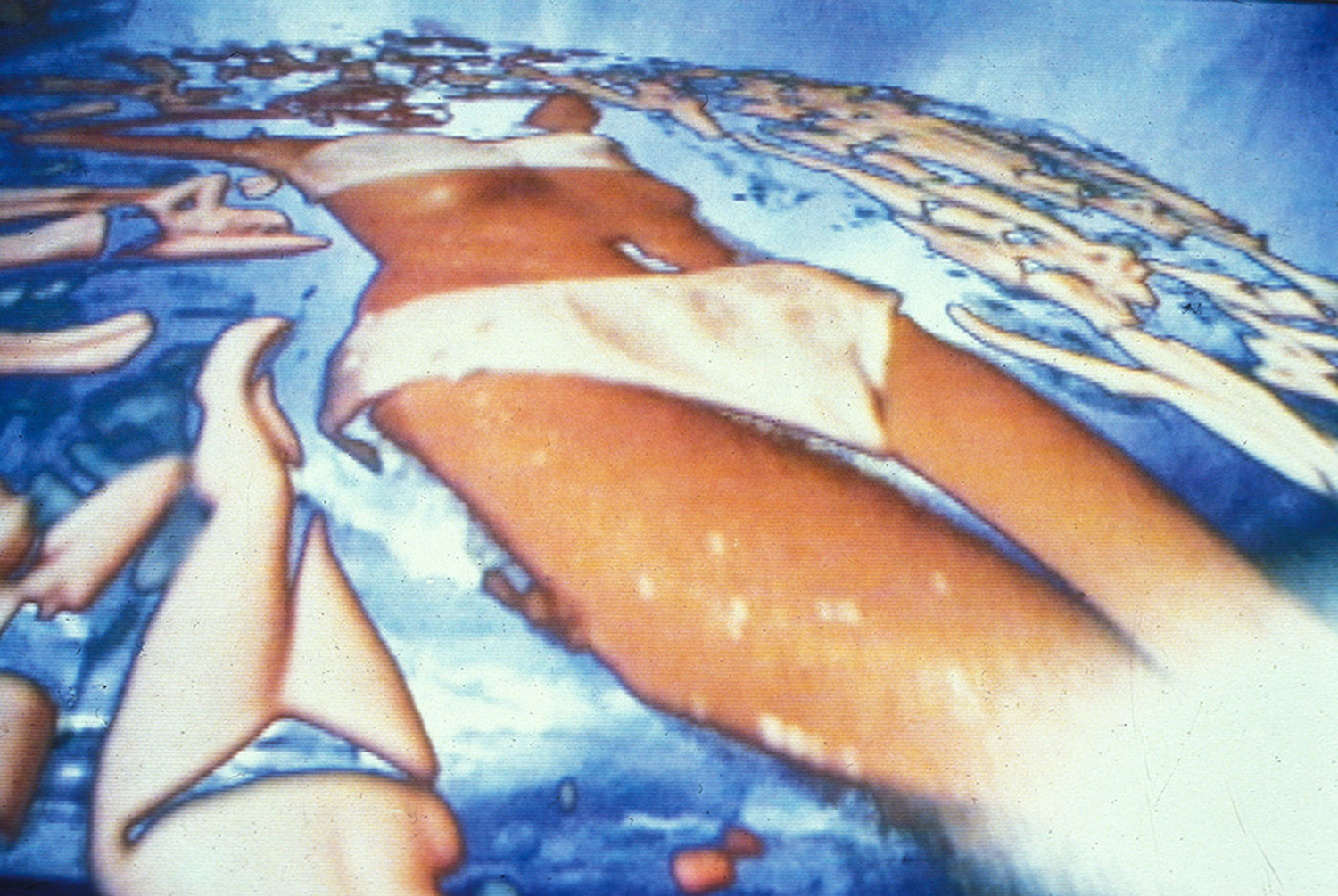

Concomitantly, the young art scene boosted the appearance of new art galleries and lead to more prestigious art galleries opening experimental spaces dedicated to the young generation. This phenomenon can be found in all parts of the country; nevertheless São Paulo, as Brazil’s most important city and the financial heart of the country, is the central example. Galeria Fortes Vilaça was one of the first galleries to invest in new talents since its beginning. Its founder, Marcantonio Vilaça (who died prematurely at the age of 37 in January 2000), set new parameters for professional art galleries and pursued inclusion of Brazilian contemporary art in the international scene, at the same time laying his bets on the young artists of the ’90s, such as Ernesto Neto, Beatriz Milhazes, Jac Leirner, Adriana Varejão and Valeska Soares, among others. After his death, the gallery continued to promote young artists, however with much less emphasis (Paulo Nenflídio and Sara Ramo are the most notable). Since its foundation in 2002, Galeria Vermelho has assumed the place of Marcantonio Vilaça in terms of presenting new talent. It has brought freshness to the art market with its mission of dealing exclusively with new artists, in particular those who have just finished college. The aim of its founders, Eduardo Brandão and Eliana Finkelstein, was to plant an experimental space where conviviality, research, risk and (also) the market could peacefully live together. The gallery has been hosting events and curatorial projects of young curators like VERBO (an annual Performance Festival curated by Daniela Labra) and ISTMO (an experimental project curated by Ana Paula Cohen that took place in Galeria Vermelho between 2005-2006). Its cast embraces artists who are starting to gain recognition abroad, such as Marcelo Cidade, Detanico and Lain, Chiara Banfi and others. Also notable within the young art scene are Marilá Dardot, Lia Chaia, Nicolás Robbio, Cinthia Marcelle, Fabiano Marques, Leandro Lima and Gisela Motta. Recently, Galeria Vermelho began to also work with experienced artists like Daniel Senise, Ana Maria Tavares and Rosangela Rennó.

Even those galleries that do not completely embrace the flag of young art still maintain strategies of renewal through project rooms and residencies for young international artists. Galeria Leme and Galeria Nara Roesler are examples of this tendency. Increased international attention on the Brazilian art system makes this a generation in transit. More residencies in Brazil and around the globe suggest a reality on the move, representing a recurrent strategy of improvement, contextualization and new visibility for artists from Brazil. Nowadays we can find residencies in São Paulo (FAAP, Museu da Imagem e do Som), Rio de Janeiro (Capacete), Belo Horizonte (Museu de Arte da Pampulha, Ecovila Terra Una, situated in Liberdade District, Minas Gerais), Recife (MAMAM no Pátio) and Salvador (Instituto Sacatar and Museu de Arte Moderna). In fact, it is much easier and more rewarding to be a young artist in Brazil than to be a more experienced one, as the main projects and efforts are focused on emerging art, creating a kind of limbo for those artists who are already 20 years into their trajectory.

I began this brief essay by mentioning the artists’ initiatives and their reaction to a dysfunctional art system. Seven years on from the first identification of this group fever3 and the improvement of art system conditions, we watch a new dynamic that articulates two places — inside and outside the institution — in a more propositional way that breaks the outmoded dichotomy between institutions and artists. Initiatives and spaces that were fundamental to and synonymous with the Brazilian art circuit do not exist anymore, like Espaço Agora and Grupo Camelo, to name just two. Some resisted, like Torreão and A Revolução não será televisionada, and new ones appeared. On the part of the institution, we can detect the absorption of the discourse of experimentalism, in particular in art museums. In this respect, some Brazilian institutions share the concerns and solutions adopted by museums in Europe, the United States and Asia. It become commonplace to open new buildings or inaugurate experimental projects, like the Octagonal Project curated by Ivo Mesquita at Pinacoteca de São Paulo. To sum up, Brazil is experiencing a revitalization and professionalization of its art system. Benefiting most from this new perspective and visibility is the new generation.