During the fall of 2015, Shanghai’s Power Station of Art hosted an exhibition titled “Calligraphic Time and Space: Abstract Art in China” — a showcase, in the words of curator Li Xu, for “the future of Chinese abstraction.” While taking calligraphy as its point of departure, Li Xu explicitly declared that the works on exhibition would contain no legible characters. They thus provided a launch pad into the space of “Abstract Ink,” defined by the diagonal line of escape that passes between the painted image and the written sign.

For all its formalistic aestheticism, the show tapped into a nexus of disturbance that connects the emergence of Abstract Ink to the question of Chinese modernity. Central to this controversy is the formulation of Chinese identity and the use of tradition, in regard to both the promotion of a contemporary Chinese nationalism and the marketing of artworks branded by an Oriental exoticism. These concerns have reactivated criticism of aesthetic formalism as an “escapist” distraction from the urgent challenges of the modern world. During the Mao era, this accusation was conveyed in both China and the Soviet Union by an imperative socialist realism (for which CIA-supported Abstract Expressionism was conceived as an antidote). The tension between Chinese aesthetics and modernization is not new. It was anticipated in the late Qing Dynasty by the juxtaposition of modernizing Western painting (xihua) with its traditional Chinese counterpart (guohua), the latter being denounced — most emphatically by the May Fourth movement — for its evasive retreat into literati formalism.

There can be no plausible suggestion that the Chinese Communist Party today is promoting Abstract Ink in anything like the same way that it promoted Socialist Realism in the command economy era. Nevertheless, under the Xi Jinping government there has been an unmistakable political instrumentalization of the abstract tendency within contemporary Chinese art. In an almost perfect inversion of the recent historical pattern, it is precisely those neo-traditionalist and formalist works previously accused of escapism that are now being harnessed to soft power aspirations. State patronage plays a conspicuous role. Indeed, the Power Station of Art describes itself as “the first state-supported museum of contemporary art.”

The terms of this controversy are questionable. Specifically, the mainstream politics of abstraction — both revolutionary and conservative — have mistakenly identified the real with the concrete. However arcane this might sound when formulated as a philosophical error, its consequences for cultures falling prey to it have been disastrous. Abstraction is the cutting edge of modernity. Those societies, which have been able to foster it at its greatest intensity, have most successfully occupied the future.

Abstraction is the bridge to the transcendental in its modern, Kantian sense. In enables a culture to access, through critique, the basic principles of its self-production. Clement Greenberg’s words from “Modernist Painting” (1960) are pertinent:

Western civilization is not the first civilization to turn around and question its own foundations, but it is the one that has gone furthest in doing so. I identify Modernism with the intensification, almost the exacerbation, of this self-critical tendency that began with the philosopher Kant. Because he was the first to criticize the means itself of criticism, I conceive of Kant as the first real Modernist.

In the Western artistic tradition, this process reached its zenith in Abstract Expressionism. By visualizing the modern trend to ever-amplified self reflection, recursion and feedback dynamics, it was attuned to the new era of cybernetics that accompanied the first wave of electronic computers. The theory of computation consolidated by a number of thinkers, prominently including Alan Turing, had understood the computer as a general-purpose simulator, capable of emulating the behavior of any machine whatsoever. It was not merely an advanced device, but an abstract machine.

Ironically, Abstract Expressionism itself drew upon Chinese models. The work of artists such as Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline and Agnes Martin exemplifies this Chinese influence on Western modernism. Calligraphy, in particular, was seized upon as a path of escape from the imperative of pictorial representation. Anticipating the twin-process of Abstract Ink, the disintegration of the image on the picture plane was accompanied by experiments in asemic writing.

In China, however, unambiguous commitment to aesthetic abstraction — and thus radical modernization — had to await a new epoch. The emergence of Abstract Ink coincides with the dismantling of the Chinese command economy through “Reform and Opening” and the arrival of commercialized digital electronics. It was the conjunction of these influences that produced neo-modern Shanghai, in which the city’s high-modernist “golden age” of the 1920s to ’40s is reanimated as a simulation, and its explosive potential released.

The Power Station of Art occupies the shell of the concession-era Nanshi Power Plant, a vast industrial edifice that stood within the disused Jiangnan shipyard. It was renovated initially to serve as the Future Pavilion for Shanghai’s 2010 World Expo. The city’s modernist heritage had become an exhibit.

Shanghai neo-modernity was the background theme of the 2010 world’s fair. The city was eager to put itself on display. Shanghai has consistently delighted in its status as an object of international aesthetic attention. Its contemporary economic function as the “Dragonhead” at the mouth of the Yangtze — and thus shopwindow for the products of China’s deep interior — is fused with cultural roots in the elegant literati tradition of its surrounding Jiangnan region, and the artistic space of the garden. Already, in the earliest stages of its modern spectacle, it was the place where China revealed itself to the world.

In their nineteenth- and early twentieth-century heyday, world’s fairs were conceived as festivals of modernization, highlighting technological advance. The eclipse of modernity has been disastrous to such grand exhibitions. By the dawn of the twenty-first century — at least in the eyes of their traditional centers — they had come to seem hopelessly dated. Within a cynically “postmodern” cultural environment, the progressive enthusiasm of the expo appears almost comically passé.

Shanghai’s delirious embrace of the expo, in all of its retro-futurist complexity, was consistent with much of its contemporary urbanism. The Pearl Oriental TV Tower (completed in 1994), the icon of the city’s dizzy plunge into “reform and opening,” is characterized by its deliberate evocation of an outmoded science-fiction imagination. This time-structure — by its very nature — is nothing new. A futuristic recapitulation of archaic forms was already integral to Art Deco, Shanghai’s signature high-modernist style, which adopted archaeological and ethnographic discoveries — most vividly exemplified by Howard Carter’s 1922 Tutankhamun expedition — as sources of avant-garde architectural inspiration. The exposed secrets of buried crypts were metamorphosed into urban design.

Despite the intrinsic temporal complexity of Shanghai modernity, the early twentieth-century “golden age” recapitulated within the neo-modern is neither simply echoed, nor extrapolated. A break has occurred, corresponding to an encapsulation or a folding. Neo-modernity designates historical discontinuity.

Shanghai’s “golden age” modern culture — or haipai — was essentially hybrid. Due to its peculiar geopolitical status as a host to “concessions” under foreign protection, the city became a refuge for millions of migrants from all over China and the world. (Extraterritoriality is a concrete mode of abstraction.) Shanghai’s mixed — and often literally outlaw — population of adventurers, refugees, gangsters, compradores and revolutionaries propelled the city to the outer edge of modernity, where the limits of possibility became uncertain. China’s commercial and cultural avant-garde, liberated from traditional constraints, adapted native traditions to a metropolis deeply infused with “international” — meaning Western — elements: jazz, coffee, mechanical printing and electricity.

The city’s modern architectural infrastructure was based upon the innovative lilongs, or lane houses, spreading throughout the city in waves, from the 1840s to the 1940s. This mass residential solution combined the density of British terrace housing with Chinese courtyard homes. Crucially, what is fused in the lilongs is foreign modernity and Chinese tradition.

Elsewhere in China, modernity was a more intractable problem — even a trauma. Chineseness and modernization seemed impossible to reconcile. Shanghai’s precocious accommodation to the modern world was therefore something akin to a national scandal, which first placed the city under suspicion, and later — with the birth of the People’s Republic of China — under vigilant discipline.

From the late Qing and into the Republican period, China’s repeated failures to achieve economic and technological take-off — dramatized by periodic military catastrophes — led foreigners and Chinese alike to identify modernization with Westernization. The attempt to balance “Chinese essence with Western utility” (the zhong ti / xi yong distinction) was a continuous challenge. Among Chinese intellectuals, the tone of discussion became increasingly polarized. Frustrated conservatives were drawn to the Boxers’ explicit revolt against modern influences, represented by foreigners and technology. The opposing — and ultimately victorious — tendency was advanced by the May Fourth and New Culture Movement, which advocated sweeping rejection of native tradition. Modernization, the May Fourthers argued, would require nothing less than a social revolution.

The foremost among the obstacles identified by the radicals was the Chinese language itself. The characters of the Chinese writing system — in their teeming multiplicity, inconsistency with linear organization and intractability to technical rationalization — were taken as the primary cultural impediment to national renewal. Their abolition became an explicit political goal. After 1949, the agenda of May Fourth found itself installed in power. War was declared against “the four olds” (old customs, old culture, old habits, old ideas). While the practical horizon of cultural revolution fell short of complete extermination of the country’s traditional language system, a drastic simplification of the script was implemented on the Mainland, under central direction.

The incompatibility of modernity with Chinese tradition, articulated by the zhong ti / xi yong distinction (and dilemma), culturally defined the country’s “century of humiliation.” It would be a misconception to think that this problem was ever resolved. It was instead bypassed by way of the unexpected transition into neo-modernity.

Cultural abstraction pilots modernization, with digitization as its most essential guide. The maddening puzzle of the Chinese typewriter therefore epitomizes a fundamental problem. The necessary attempt to mechanically digitize the Chinese language was a computational challenge that absorbed immense cognitive energies, from the Ming Kwai typewriter patented by Lin Yutang — an intellectual who incarnated the dilemmas of Chinese modernization with peculiar intensity — to the myriad experiments of anonymous typographers and semiotic technicians. Thomas Mullaney argues that this diffuse research undertaking — even in advance of its formulation as software — had already stumbled upon predictive text.

Within computerized neo-modernity, this entire predicament was dissolved. The “reform and opening” after 1979 coincided with global mass commercialization of electronic technology, which offered an implicit computational solution to the Chinese typewriter problem (through digital decomposition of scripts). The crossing from the tantalizing dream of the Chinese typewriter to the vast reality of the Chinese Internet was a matter of mere decades, under near-automatic propulsion. Chinese cultural modernization, for so long a seemingly unreachable objective, was suddenly an established fact. Neo-modernity occurred as a euphoric jolt — in a key stroke.

The most striking evidence is provided by the mobile phone — a ubiquitous, increasingly text-oriented, digital communication device — that has spread throughout the country and installed itself as fundamental cultural infrastructure. The explosion of Chinese signs within computer systems has accomplished a semiotic revolution without obvious parallel. The calligraphic sign, which for over a century stood in dramatic opposition to modernity, has been smoothly integrated into neo-modernity. Steve Jobs famously credited his college calligraphy education for Apple’s critical switch from textual functionalism to typographical aesthetics. Today, mobile applications using Chinese script are positioned at the leading edge of translation software and machine learning.

Neo-modernity is a refolding or doubling-back, expressed through a digital reanimation of traditional culture. In the arts, this electronically facilitated neo-traditionalism extends far beyond the Chinese writing system, narrowly conceived. China’s ancient religious-philosophical teachings — the gods, rituals and concepts of Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism — enter the order of simulation (or computation). This is exhibited with particular extremity in the work of Lu Yang. Her The Anatomy of Rage series (2011) splices together Tibetan Buddhism with contemporary neuroscience, transmitted through electronic media. Digital technologies now conduct an archaic cultural content, rather than supplanting or extinguishing it.

Neo-modern art is defined by an innovative recycling of tradition. One remarkable example is provided by the reconstruction of Chinese landscape painting (shanshui) from anachronistic elements. Yang Yongliang constructs classical shanshui compositions using urban-industrial photo montage. Chen Chun-Hao uses a nail gun to reproduce the densities of the shanshui grayscale. Yet, neo-modern time folding does not depend solely upon the novelty of the creative medium. The primal element of fire, with its deep roots in many varieties of Chinese religious ritual, has been employed to radically rework artistic practices, whether as controlled paper-burning (Wang Tiande), incense-stick ash (Zhang Huan) or gunpowder scorch marks (Cai Guoqiang).

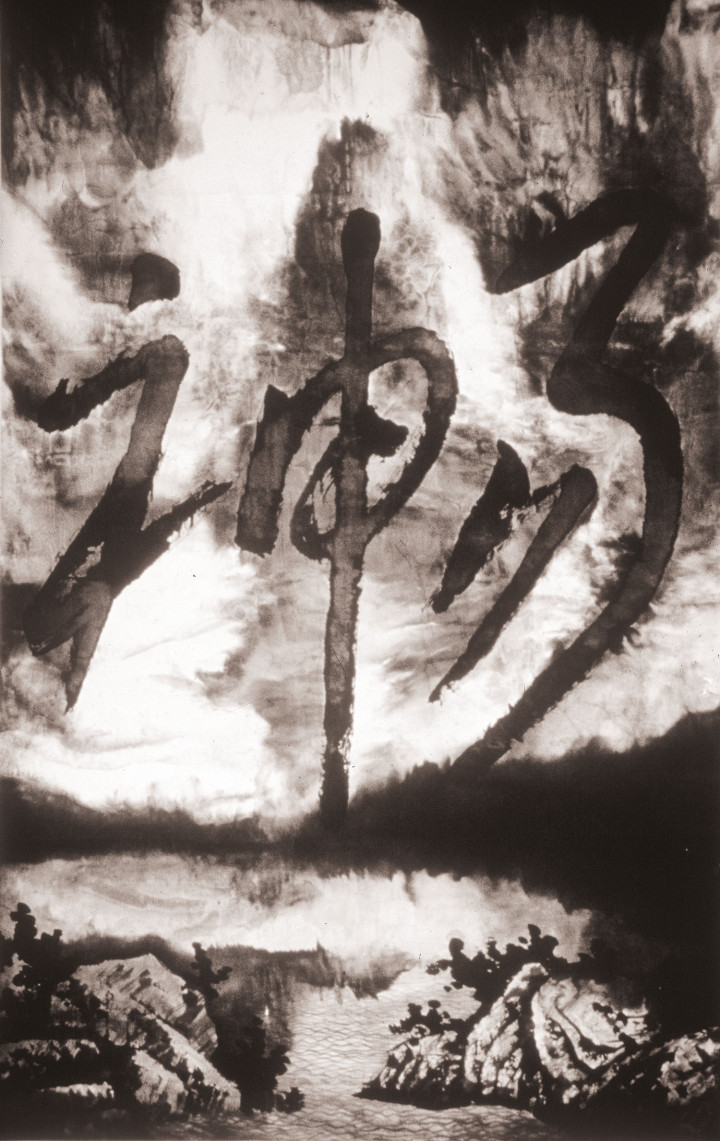

Calligraphic experimentation pursues the neo-modern line further into abstraction. Synthesized Words (1985), by pioneering Abstract Ink artist Gu Wenda, simultaneously releases writing from signification and painting from the representational image. Qiu Zhijie’s Writing the “Orchid Pavilion Preface” One Thousand Times (1990–95) propels itself into abstraction through ritualistic calligraphy, with an emphasis on performative process — recorded on video — that culminates in the obliteration of distinctive form and meaning in inky blackness. The gestural abstraction of the calligraphic stroke, explored in China as early as the eighth century, is manifest also in the work of Shao Yan, whose action painting reaches forwards and backwards, into the common origin of writing and martial arts.

In the West, modernist abstraction arose as a rebellion against a tradition dominated by principles of representational fidelity. In China, and neo-modernity, the path is far more paradoxical. Abstract Ink taps reservoirs of abstraction inherent within the three ancient teachings (Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism). The extremities of the abstract thus tend to coincide with the most explicitly neo-traditional work. Gu Wenda did not reach asemic writing through revolt. Instead, he reactivated China’s archaic and now generally-illegible “seal script” as an artificial language with which to escape image and word. To the virtual consternation of both its conservative supporters and radical critics, “the future of Chinese abstraction” converges with its past — in an intrinsic complication of identity. It is by folding back into tradition that neo-modernity opens the doors of abstraction. The free diagonal line released in ancient China has yet to reach us. Shanghai has long been preparing to receive it.