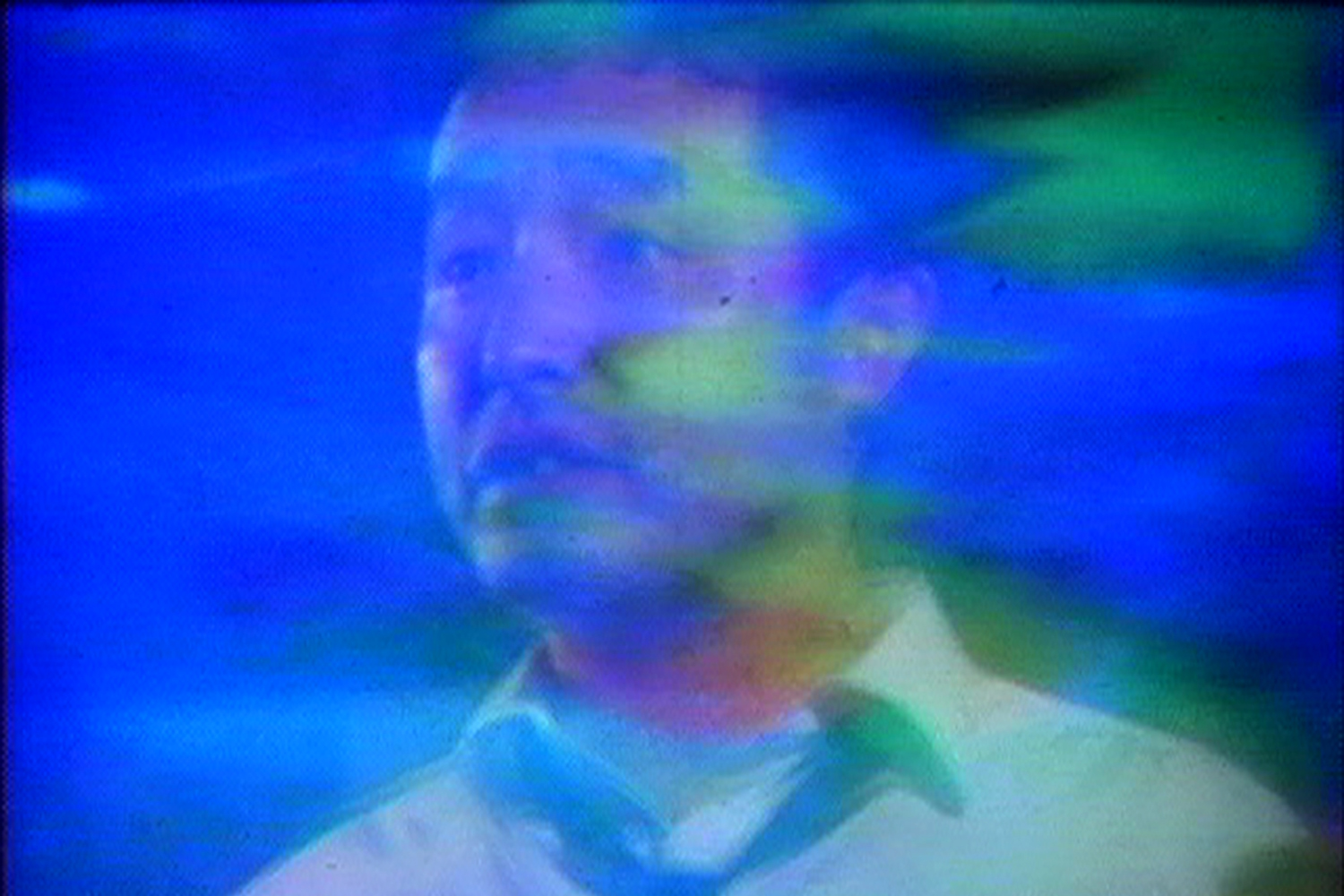

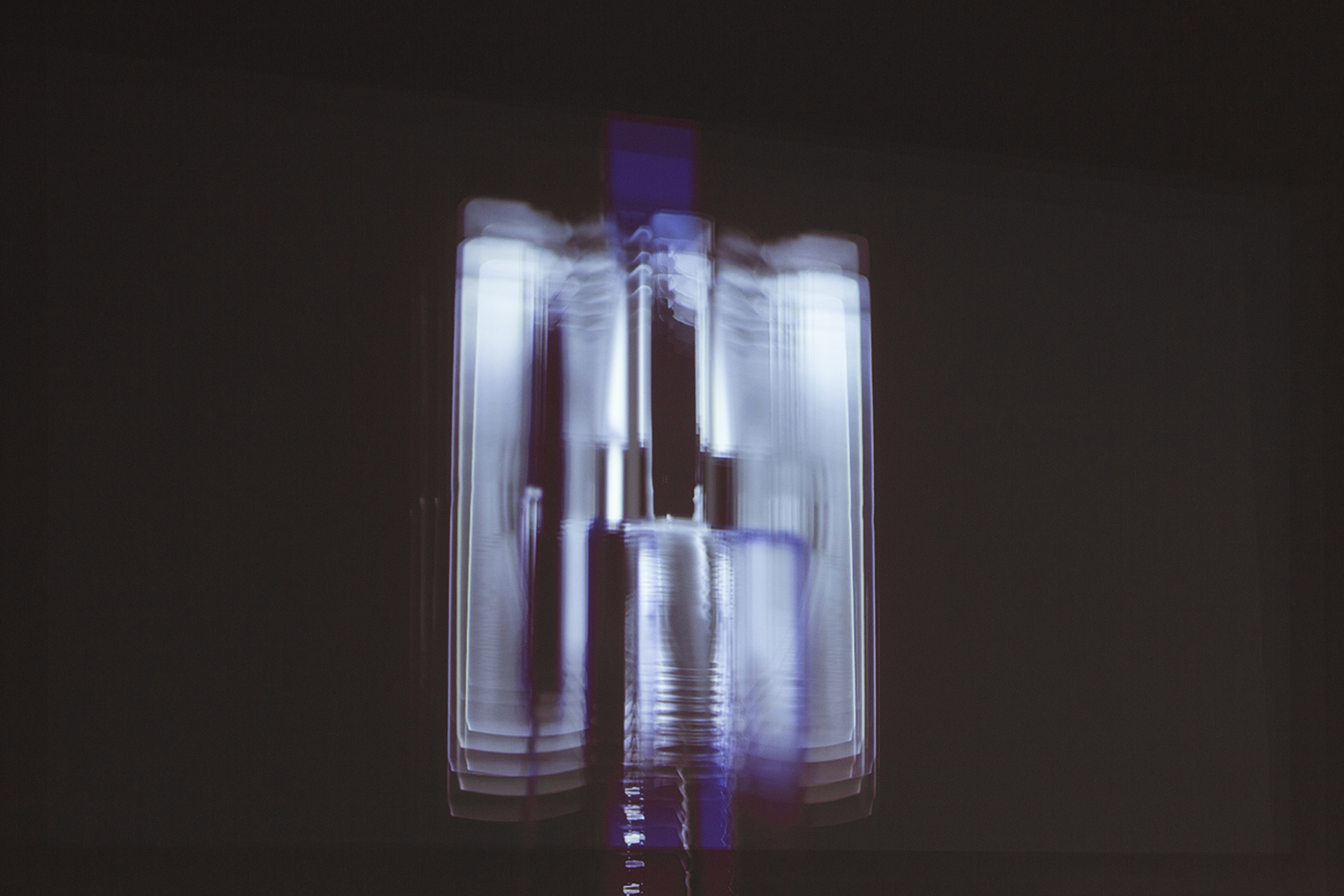

Tate Modern’s Nam June Paik survey is zeitgeisty — immersive and Instagrammable, like Olafur Eliasson’s concurrent show in the Switch House extension. There are direct similarities between Three Camera Participation/Participation TV(1969, 2001) and Eliasson’s 2010 installation Your uncertain shadow (colour). Viewers’ bodies produce the same soft, Day-Glo silhouettes. Parts of Paik’s work prefigure the emergence of “experiential art” and a shared, embodied mode of viewership, which came to prominence when camera phones and social media arrived in the 2000s. The stultifying formality of galleries, the convention of quiet, solitary contemplation gave way to spaces that encouraged you to interact with art, talk to friends, laugh out loud, share pictures online.

Held as “the inventor of video art,” Paik was ahead of the curve in lots of ways, but was particularly forward-thinking in the way he sought to bring art to everyone, all over the globe. “PURGE THE WORLD OF ‘EUROPANISM’!” cried George Maciunas in the 1963 Fluxus manifesto. As a key member of that experimental art movement, the Korean-born artist attempted to decenter Western art and redress the historic marginalisation of Eastern practices. The Mongolian Tent, Paik’s contribution to the German Pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale, draws influence from shamanism and Central-Asian tribalism. Sistine Chapel (1993) rewrites the renaissance. A dozen projectors beam images on every wall. Playboy covers, psychedelic visuals, footage of Asian nomadic communities fill the gallery with colour: an alternative to Michelangelo’s ceiling.

Like media theorist Marshall McLuhan, Paik believed technology would deliver a better future. In his 1974 essay “Media Planning for the Postindustrial Society – The 21st Century is Now Only Twenty-Six Years Away,” Paik sets out a vision of a technological utopia. He dreams of “electronic super highways,” an intercontinental, high-speed telecommunications network that he thought could unite geographically disparate cultures and bring lasting global prosperity. Good Morning Mr. Orwell, a video recording of Paik’s first live, international TV broadcast on New Year’s Day, 1984, was intended as a rebuttal against George Orwell’s dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), in which telecommunications serve as a machine for state propaganda and surveillance. The work not only anticipated video call services like Skype, but also the way digitised museum collections have provided free, online access to the world’s cultural knowledge. Two hosts, thousands of miles apart, one in a TV station in New York, the other at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, present a mix of live music, dance, computer animation, experimental art, and popular entertainment while counting down the New Year.

However, notwithstanding works like Guadalcanal Requiem (1977–79), a film produced in collaboration with the cellist Charlotte Moorman, which retraces and restages a bloody Allied offensive against the Japanese during the Second World War, Paik’s idealistic conception of technology was fundamentally deterministic and ahistorical, entirely out of touch with the violence seen throughout the twentieth century, not least in Paik’s native Korea, torn asunder by the Cold War. Technologies do not develop out of nothing. As Aaron Bastani writes in Fully Automated Luxury Communism (2018), they reproduce the political, ethical, and social contexts from which they emerge. “Technology makes history — but not under conditions of its own making.” While technologies can affect revolutionary change for the better, they may simply replicate the horrors of the past.

Lewis H. Lapham wrote that McLuhan was “always sure that the whole world could be made to fit into the trunk of his hypothesis, bestowing on audiences […] the gifts of Delphic aphorism.” He could have been describing Paik: a pan-national, forward-looking utopian who was not always justifiably sure of the virtues of technology.