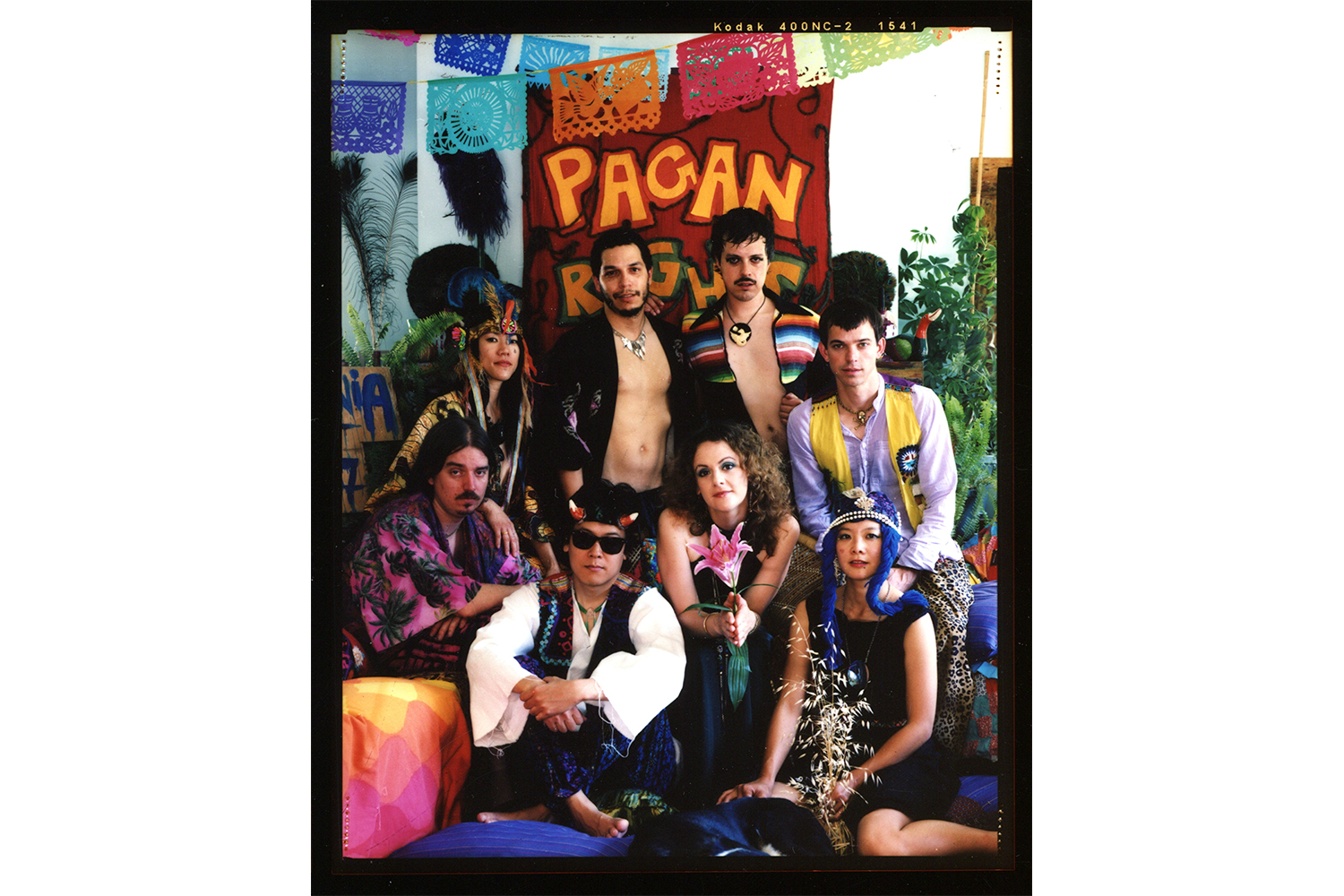

“We were born Generation X, officially, which is embarrassing to admit but true,” says interdisciplinary artist and member of My Barbarian Alexandro Segade, speaking about the collective similitude within the group, which includes performer and writer Malik Gaines and actress and artist Jade Gordon. Some of the defining characteristics of those born in Generation X have to do with burgeoning youth cultures amid the AIDS epidemic and the disintegration of the Eastern Bloc — those who were strongly affiliated with underground, outlier, and/or queer scenes alongside major cinematic and music franchises.

The proliferation of this sort of counternarrative crossed with pop culture has resonated between the three since My Barbarian’s conception as a nightclub act twenty years ago in LA during their college days. Now, the core members have carried their performance into institutional settings, working from their own conceptualized genre called “showcore.” The term describes a self-reflexive methodology tied to the histories of musical theater and queer camp aesthetics, as well as their close attention to more noncanonical show-biz devices.

So much has changed since those early nightclub stages, from the group’s interpersonal relationships to the discourse that the work attracts, which continues to evolve as it is performed before different audiences today. I spoke with Gaines, Gordon, and Segade during My Barbarian’s current show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in LA, which followed a survey exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art as well as the release of their major new publication. Both the exhibitions and the book give close attention to the scope of objects, costumes, and more sculptural aspects their live show practice. This opus ventures into a performance practice that pokes fun, or even masks themselves, within and against the bounds of the museum-institution.

Jazmina Figueroa: We’ll start the conversation with the conception of My Barbarian. Can you paint a picture for me of what it was like in the scene that you three emerged from in LA — this theater nightclub scene?

Jade Gordon: We didn’t necessarily come out of an experimental theater scene, per se. We were all living in Los Angeles at the same time. I was an actress at USC, and Xandro was in film school, and Malik was at CalArts doing an MFA in writing, and we started doing some theater and film projects together.

We realized that it was challenging to produce work, financially challenging and logistically challenging, but we had a hunger to perform and be on stage. We started as a musical trio that expanded to include other musicians. As we were performing all over Los Angeles in nightclubs, we realized that it was an amazing opportunity to have a set amount of time on stage, with no rules other than we would be amplified and we would probably be playing music. It was a chance to perform without having to produce an expensive piece of theater or be pressured to sell tickets or generate an audience, because there was a built-in audience that would attend these clubs and music venues. We used the opportunity to just be on stage and work out some of our issues.

Out of that, we brought musical theater to the nightclub. We realized that we confused the LA underground music scene, but we were interesting and attractive to art audiences. We started getting invitations to do our musical act, and from there we realized that we were able to generate more material, be more prolific, and do new work more frequently if it was just the three of us working together.

Malik Gaines: At that time it was a slightly looser place in terms of what discipline you are working in. There was freedom there that we took as permission to do music as performance art, as theater, as visual art, as a nightclub act, and as a live event in a public space. We took that permission seriously.

Alexandro Segade: I don’t even know how serious it was then, but we were working within the band scene, and it seemed like everybody had a “core” — a musical genre that everybody was inventing for themselves. And we came up with “showcore” as a way to bring together all of the ideas we had around performance that included a fantasy of show biz. That was also a way to embrace queer camp aesthetics alongside the DIY mentality of our band. This sensibility is something that we’ve carried through from that period.

JF: I like the term showcore to suggest liveness as the core of the work. You’ve defined showcore in ways that relate to the Whitney show, now at ICA, but the work involves so much more than the live show. How is that captured in this exhibition?

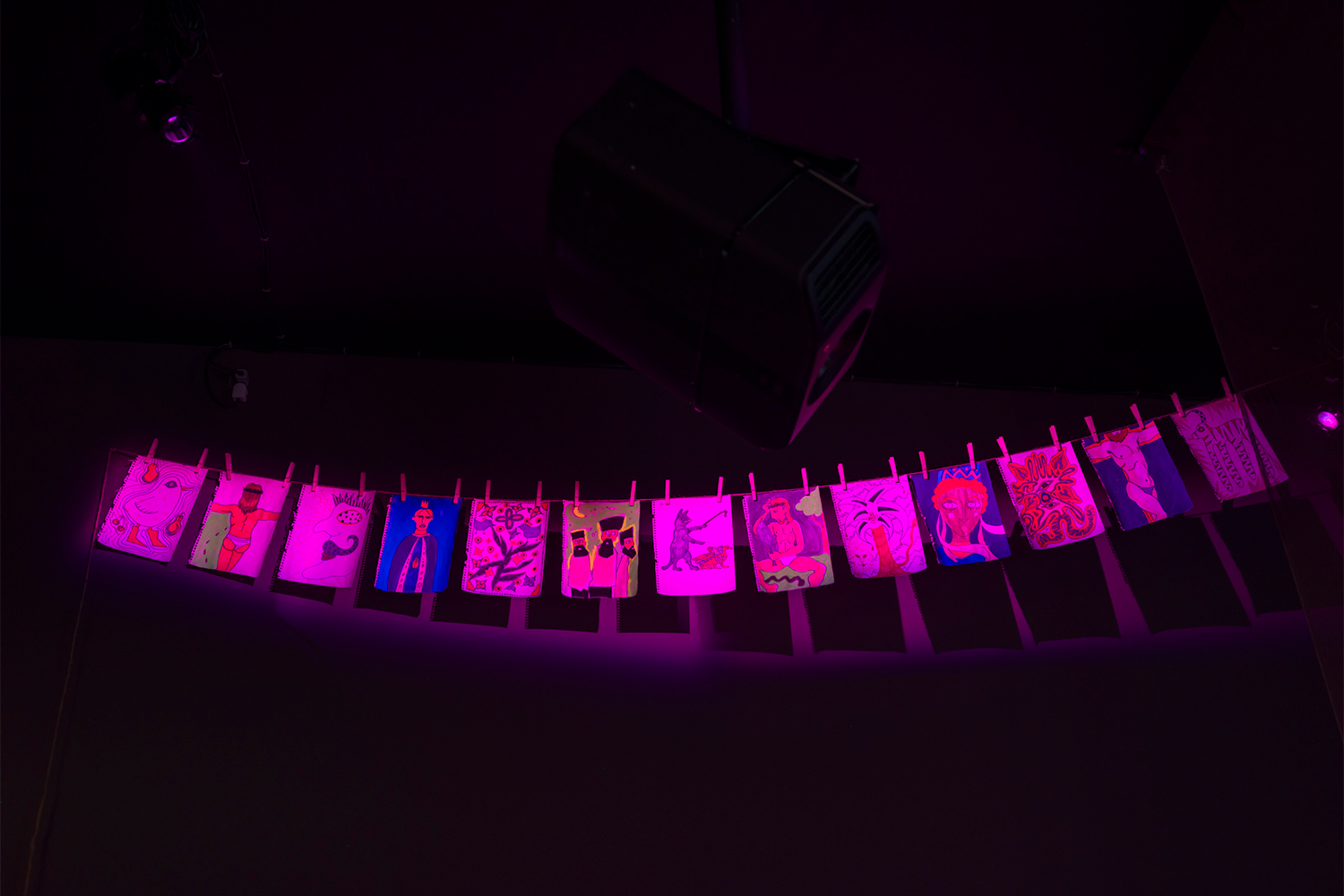

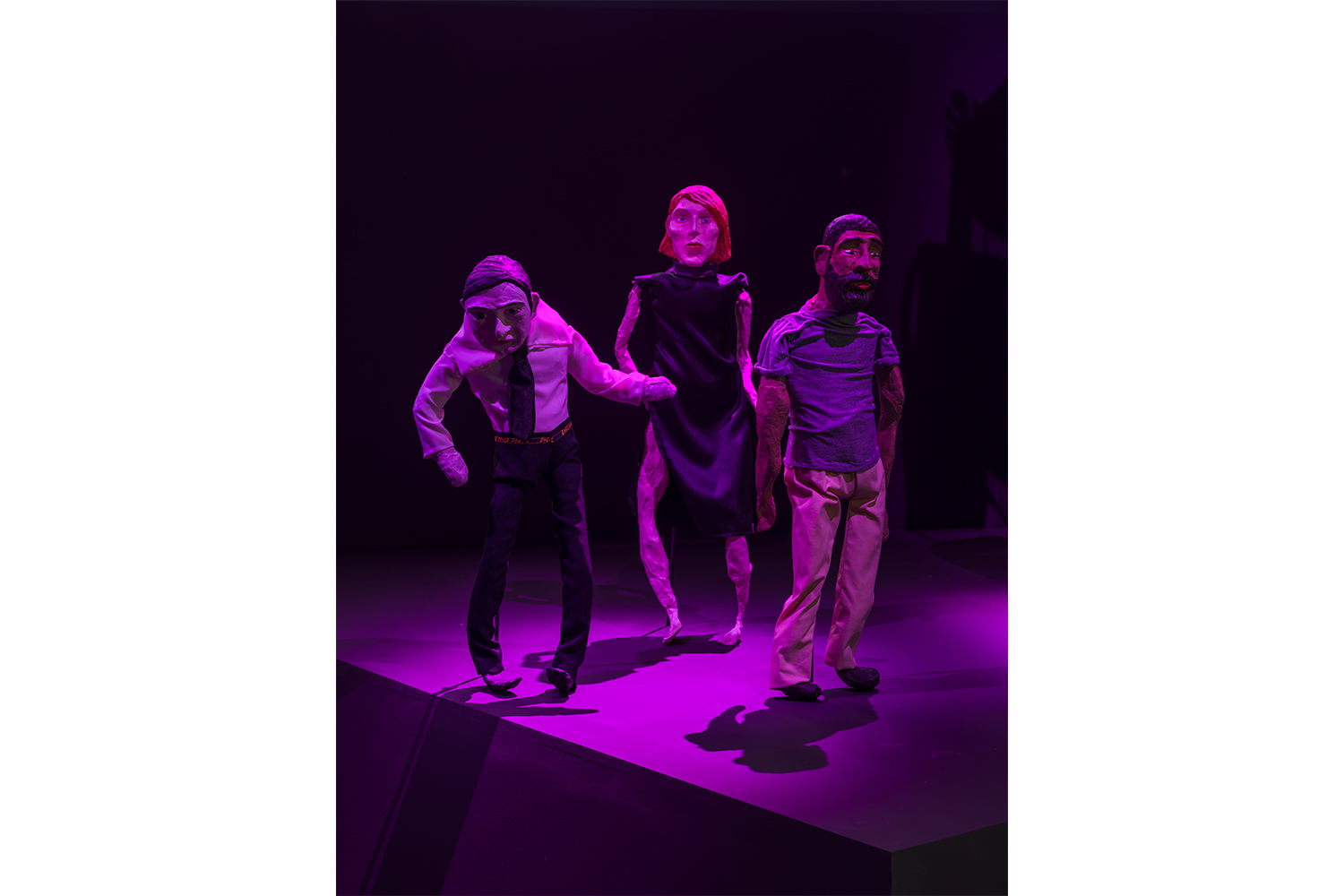

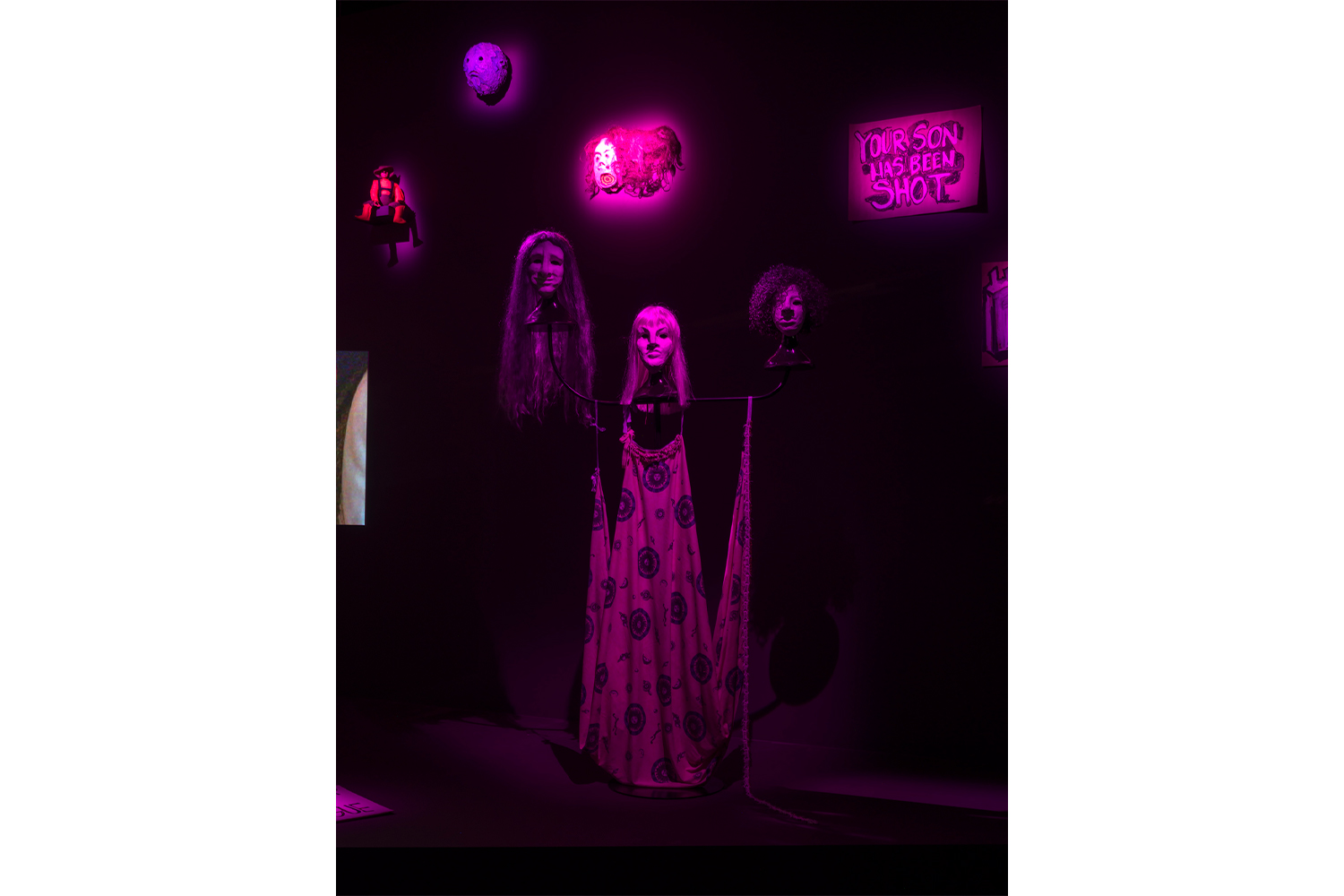

AS: The way that is reflected is in trying to bring some liveness to an otherwise potentially inert exhibition. We use theatrical lighting, and the three-channel video installation activates the space in a very literal sense. We use a theatrical dark room, stages, drawings, and masks to focus on certain performative elements of what otherwise would be seen as sculptural objects. The real embrace of those theater apparatuses brought into the gallery space is enlivening the work. Liveness is important, but so is the spectacle and the handmade quality of that spectacle. One thing I like about the current exhibition in LA is that it’s in a smaller space [than the Whitney], so it’s closer. You can see fingerprints on the mask, and that’s the showcore sensibility through performance, theater, or imagination.

JG: A through line with our work is revealing the backstage, the seams, and these kinds of handmade elements. Shortening the distance between the spectator and the objects makes visible those kinds of cracks, like, literal cracks and seams and dirt, and having the costume’s wear visible underscores that the objects were used outside the gallery space. I saw a big-screen version of The Wizard of Oz several years ago, and it was so amazing to be able to see the seams of the cowardly lion’s costume. This made me think of our work and our practice of getting up close and seeing that artificiality, in the middle of a fantasy spectacle. We talk about them on stage, in our adaptations; we step outside of the historical text and comment on it and talk about it. In performance, it’s the same situation as the objects in the room.

JF: Is that because you’re interested in this layer of authenticity in the work, or does referencing those imperfections have to do more with spectatorship? I’m thinking of “The Audience Is Always Right.” I would like to hear some of your ideas on spectacle and the audience that emerged from that program.

MG: The question of authenticity for us has always been about reversing the expectation of transparency in the structure of the text — the fact that we are performing on stage and refusing to have a separation from the audience. All of that points to the real of the performance. For us, that’s grounded in trying to think of performance as integrated with our politics, our social world, our environment, the power exchange we’re having with the audience, and the power exchange we’re having with institutions.

On the other hand, we’re students of that performance art history, that visual art history, that dance history, and that theater history. We consciously move toward theatricality as a way to be bodies in space. While the performance’s social context is authentic, we also use narrative, costume, fantasy, character, and dialogue to play through all of those social conditions rather than insist, “Well, I’m an authentic body here. I’m material like a sculpture.” With My Barbarian, there is no singular performing body at the center. The three of us came up with a way of being on stage together that was more about relation than presence.

“The Audience Is Always Right” was a series of political theater workshops between 2008 and 2016 that we toured and had an exhibition. We figured out this three- person relational way of performing: it has techniques, we have priorities, and we are a community, family, or company. How do we bring these social practices to larger groups of people? What might that tell us about social projects like democracy? That’s how we ended up doing Post-Living Ante-Action Theater and the exhibition “The Audience Is Always Right.”

JG: There is a tension or an ability for us to simultaneously hold the authenticity of being consciously together on stage and in conversation with an audience. There’s also the element of rehearsal and those kinds of theatrical tropes; we have lines that we memorize and we can repeat these lines multiple times. It’s not something that only happens one time in space. That inauthenticity, extra-realism, this theatricality that’s not often welcome in white spaces… That’s an interesting Freudian slip — I mean white gallery spaces, white boxes. An awareness of and conversation about [theatricality] is happening while we’re on stage as well.

MG: Whiteness, heteronormativity, and the way that those attach to aesthetic expectations are something that comes up repeatedly in all of these projects.

JF: You’re talking about the theatrics and the styles that you’re working in to approach, let’s say, the whiteness of the gallery space. I especially like the reference to the baroque in Broke Peoples’ Baroque Theater, as it has to do with excess and colonial expansion in the baroque era. In simplest terms, it’s a project of excess. What’s your interest in the baroque or theatrical excess?

AS: We’ve been working for twenty years, and some things that weren’t different about the three of us have changed as well as the discourse around the work. A certain type of excess, as opposed to minimalism, was our set of influences. There was an excess of culture that we were sorting through, in part because we were coming from three different places. What we have access to is different, and then we bring it into one room and it feels excessive already.

In terms of the baroque, what we were thinking about initially when we started the project in 2011 was the oppressiveness of this Western canon. This idea of using white masks that Jade developed from her commedia dell’arte training, and I started making these elaborate toga goddess gowns that were influenced by Versace but were made out of the cheapest materials. Also, we were thinking about class and the way minimalism signified wealth in the art world — the fewer things you had in a room, the wealthier you were — and the ways an excess of culture signals a class.

The baroque as an adjective and historical period was useful to make sense of all of these influences. Also, coming to terms with all the violence that was inherent in these narratives that we were inheriting.

This weekend we’re doing The Broke Peoples’ Baroque Theater. We’re restaging it in its biggest form. The four short plays in it are adapted from canonical theater texts, which we feel are the only things that we are allowed to touch anymore in the sense that nobody wants them, but they’re all there. We’re playing with some Shakespeare, some Euripides, and some Calderón de la Barca. Also, Aphra Behn’s novel Oroonoko is about an enslaved royal from Coramantien, written in the 1600s. In doing these interpretive commentary works around those pieces, they track our conflictual fascination with this history and its stuckness with these legacies.

MG: The weird class position of being artists who perform. For example, when we were younger, we would be asked to sing and dance at a gala dinner, so what is our class exactly? We’re surrounded by the wealthiest people in town. We get free drinks, but we’re treated like we’re also waitstaff; being in that artist position is often being in between class positions and having that view of that excess. Coloniality as a form of excess has always been in this work: to think about territorial expansion, the condition of violence, or the duration of that [colonial] project within this repertoire of excess.

JF: Also, this excess of extraction that is so present right now and for the generations to come, shows how the colonial project impacts our environmental situation today.

AS: When you work with a twenty-year project, you see how certain themes resonate over time and things come up again. Even talking about the way that the larger discourse has shifted: we were coming out of institutional critique when we started Broke/Baroque, focusing on the artist’s position in this mechanism. Now we’re looking at much larger questions around extraction that don’t center on the artist being caught in the matrix, but actually as a participant in the machinery.

JF: Do you think your 2014 work Double Agency also stems from these ideas?

JG: Double Agency marked a moment in our practice when we began to have a different relationship with object-making and showing work. That’s always been an ongoing conversation for us as a collective and in terms of survival: How do we sustain our practice? We started consciously making objects shown differently from the way we were showing work before. Also, we have a shared interest in pop-culture genres. We’ve done other works that reference specific genres, whether it’s theater, television, or music.

AS: Which I think connects to the masquerade, which is a keyword for us. In the original wall text for our show they had the word absurd in there. We were like, “No, no, not absurd. Carnivalesque.”

There are very particular things we are working through that connect to the functions of the mask. That became the object that we were able to cohere around as a group, leading to costume and other elements of theater becoming sculptural. In part, it is because Double Agency suggests an untrustworthy, shifting thing that doesn’t always have a clear status.

With LACMA, we asked them if they could just give us a breakdown of all the masks in the collection. And they cut through all of the different areas of the collection, which are divided mostly geographically and then sometimes historically. They’ll have an area that’s Africa and Oceania, but then Western art catalogues every five minutes of Western history.

Within the duplicitousness of the mask itself, and the erasures in the collection, it just seemed like making forgery was the only solution to engaging with that institution in that way.

JG: There’s a connection between masks as individual objects and then us as a collective wearing the mask of a particular genre and then thinking about these alter egos. In a lot of our work, we create these alter egos. Masks help facilitate that, and genre helps facilitate that. It’s a big, giant, collective mask — the mask of My Barbarian or the mask of the character, the group that we’re playing at the moment in a fantasy or particular mythology or a moment in history.

AS: And by mask, we also mean wigs.

JG: It’s all masks. The behavior, the body, the suggestions, the costume. It’s the image and the archetypes…

AS: And the space between the mask and the body. What’s cool about that, even as a metaphor, is that you turn sideways and the mask doesn’t work anymore.

JG: We consciously manipulated those distances in an adaptation of Brecht’s The Mother, where we made the masks so they wouldn’t fit on our faces and we had to hold them. That distance was very intentional — it was malleable. We could put them up to our faces and do an aside to the audience, and it was a physicalization of a performance mode and that is very comfortable for us. We were stepping in and out of the scene and our relationship with the audience.

JF: I want to point to a related work, Hystera Theater [2009-19], which, from what I understand, focused on the inaccuracies in the media’s depictions of maternal grief. As a collective, how do care, attention, and necessity facilitate the process of making a work like this? How do themes get translated into a piece like this? And can you describe the ways that you come into the themes and the techniques that you explore, write, and produce from?

MG: There was a point in My Barbarian’s history where we all went back to grad school at the same time. There was a situation where we had to do something in a small corridor space, and we had been interested in Luce Irigaray’s Speculum of the Other Woman (1974), which has a section called “Plato’s Hystera.” We were interested in the language and this idea that Plato’s cave is patriarchal anxiety about a feminine space making representation untrustworthy. Irigaray reverses that by turning the cave into a womb. That was used as a design technique to make a series of red text banners and costumes and to fill this corridor space with a bunch of musical performances that play with this trustworthiness of representation and the biological part of that image and the feminist critique. That was in 2008, and we revisited that work for a film we made a few years ago, in 2019, in which Jade did a significant amount of editing and referring to these passages of maternal grief.

JG: Part of our process is revisiting earlier work through the lens of lived experience and developing things and taking them in different directions, in response to the current political and personal moment. We were invited to be in a group show, and we decided to revisit this content with new footage that Alexandro shot using masked dancers in New York. We were living on two separate coasts at that time, and even our work process was forced to change, rather than working together in our studio in Los Angeles or together in New York.

I lost a child to cancer in 2018, and it was the first project that I was able to do after the death of my child. He died of a brain tumor. It was the first time that I felt compelled to deal with my personal stuff inside the container of My Barbarian. I was looking at misrepresentations of maternal grief that I had been familiar with from 1980s melodramatic films, and editing together bits and pieces of really extreme, hysterical maternal grief. It was a way for me to process my own grief. It was always going to be a misrepresentation out in the world, because nothing can actually depict that particular individual experience. Layered on top of a musical score is, “You were born poor and poor you will die,” because there’s a collective grief connected to these realities.

We made a vinyl album and a 16 mm film from the newer video work that Alexandro was developing and editing with the old footage. It was an interesting direction for us to go in. I feel like it’s one of the pieces that was really expanded, and we were able to add some personal emotional depth to the work. In this way, there wasn’t a Brechtian distance as much for me in this particular piece. When I see the work — and I think other people have commented when they walk into the space in our installation — it is very emotional. And it’s an emotionality that is unfamiliar maybe to My Barbarian audiences who know our older work. We deal with pain. We’ve dealt with pain for twenty years. Is it removed or is it a lived experience at that moment?

JF: Dealing with pain that spans our lives and the things that happen to us, or the things that we exist within, leads me to think of margins as having to do with something cultish — an outlier. Or the impossibility, the un ness of, let’s say, a body or the body’s experience and a margin’s impossibility within an institutional context. How is that associated with My Barbarian and how is that informed by each of you? For example, Malik’s book Black Performance on the Outskirts of the Left: A History of the Impossible or Alexandro’s recent essay on #unalive.

MG: Absolutely, that image of My Barbarian is romantically attached to the very beginning, it’s outsider. We put my in it to make it familiar and endearing. We had an exceptionally good ability to be in institutions. That position has been a subject of our work, and it comes from a place of actually having an idea of what’s inside and looking at it from there.

I am coming from a position of Black studies within performance studies, and all of that asks, “What are these kinds of forms of belonging in the first place? How are they organized?” That’s something I trace through both art and performance in my own research, and it’s a set of questions in My Barbarian’s work as well.

AS: Biography is sometimes hard to talk about because that’s the thing that separates us. It also is what unified us for twenty years as people working together. When we see the canonical art histories, we realize that no one who we’re paying close attention to exists in those histories. One of the things I’ve been interested in in my writing is an ambivalence created when you bring influences and references that are not supposed to be in that space. We’ve done that through My Barbarian — and I would say it’s been moderately successful — with support from institutions, to do things like a survey exhibition at major institutions.

At the same time, we’re not the dominant conversation ever. That’s okay. We’re not asking to be. We want to bring theater into the white cube and then completely create this ambivalent relationship between those two fields that ends up questioning both. I know from conversations with other artists who grew up the same way I did, and younger artists coming up, that they’re influenced by a much wider field of media representations than what happens in the white cube. What’s marginal and what’s not is contextual.

JF: There are the fast-paced media formats of today where things just get thrown at you and absorbed and then spat back out and then recontextualized.

MG: Back to that origin story that Jade painted, it was a different time. It was the late 1990s, the early 2000s. Jade was having some success in Hollywood. You saw her in TV shows and movies. It seemed from our point of view that what was available to her as a young blond woman was a limited set of parts. No one at USC film school wanted Alexandro to make queer Latinx movies, and I was looking at the path for my queer Black plays, thinking, this is a real slog to get these things out there. Now, not only could we be TikTok stars, but we could possibly have an HBO show. There was no format for anything like this then — even performance art was a hard sell. There is pain and difficulty in looking at the archive, but some of the pleasure of looking at what we did is seeing the boldness and inventiveness and fun we had with the creativity of making up our own form of work and our own audience for it.

JG: The camaraderie and the safety of the group facilitated a lot of the work as well. We would go places together and feel validated by and mirrored by each other. Even though we were very odd. Even when we were on stage, people would yell out, “Who are you? Where did you come from?” And not in a good way. And we’d look at each other and be like, “Yeah, we’re doing great.” That relationship and collaboration were sustaining in themselves, and maybe that is why the group is still working together, even though that can be painful sometimes too.

JF: How do you decide what to include in a show like the one at ICA — from this massive archive of works and things? How long does that process take for you?

JG: I think the COVID lockdown was helpful in a strange way to facilitate the editing system. We took a deeper look at over 250 hours of footage that was on videotape — miniDV tapes. So we created the archive and then we started working through it. Eventually, it became clear that if we were going to have a cohesive and coherent installation, there had to be some kind of connection between the objects on the walls and the videos. There is still so much that wasn’t included in this installation because there weren’t connections with objects to every single piece of video. That became the deciding factor — if there was a corresponding object to the video. Is there a costume? Is there a drawing?

AS: There was a real feeling that these choices had meaning and that there was a possibility of life after the performances. It was a way for us to make sense of what we had done, because I think we were working the same way most people were pre-pandemic, which was just, like, take every opportunity that makes sense, don’t look back, never have enough funding or time, don’t expect care from institutions, be treated terribly and just keep working. We didn’t have a chance to look at what we were doing.

We were planning to do volume two of the survey because we have two more hours of edited material that doesn’t necessarily have corresponding objects. This show ends up becoming indicative of what we were talking about earlier, our relationship specifically to the mask and to masquerade as a coherent way to think about that particular body of work. On the other side of that, we’ll see what kind of logic emerges when we put together the other volumes. But it made a lot of sense to start with that. There’s a bull mask that’s the central image. They stand with these phalluses and breastplates and this bull’s head. In a lot of ways, that’s where we have to start: theater and ritual, masquerade, play and genre reference; all that is in there. Then we’ll see where the next layer goes.