When I was living three driftless years in Berlin, I, like all residents, new or otherwise, would have to register activities at the local town hall. In my case, with an apartment that straddled two boroughs, that meant visiting the Kreuzberg Rathaus (town hall) on Yorckstraße. Cast in the city’s trademark gray concrete, I would pass through its small atrium, filled with a couple of leaning, underloved tropical plants, and take the lift to the third-floor housing and finance office. Like a hospital, it ran on a triage system, coordinating all the essentials of bureaucratic life, from housing to registering for taxes. You would line up to enter a small office, with one door for entrances and another for exits, where a helpful but brusque woman would patiently listen to your faltering German and hand you a ticket. At that point, you’d park yourself on one of the SIF Formica chairs, look out over the slate-gray faux-marble linoleum and wait until your ticket came up on the screen.

When I arrived, in the wake of 2015, when the state accommodated more than 1.3 million migrants with their usual potato-y pragmatism, people would warn me about the length of the queues. By the time I left, in 2019, when I went to get my official deregistration stamp, it was back to the normal state of Berlin, a city which, outside of its assigned hubs of chaos, always felt like walking through a stage set with only a third of the extras. At the top of the building there was a small canteen serving traditional German food and filter coffee. Thanks to its height on the twelfth floor and its glass casing on three walls, you had an unrivalled panorama of the city, a city that had seen five countries over the last hundred years, with a view over the boulevard that, coincidentally, was always filled with green leaves whenever I visited. Sitting there, munching a weirdly brutalist egg brötchen — these were, looking back, some of my happiest memories, being as I was a citizen with the paperwork to prove it.

This is an essay about bureaucracy and the recent Prada SS21 show. It’s about the idea of the model citizen, why it is now possible, urgent even, to think of this romantically, and how we might reconsider a public.

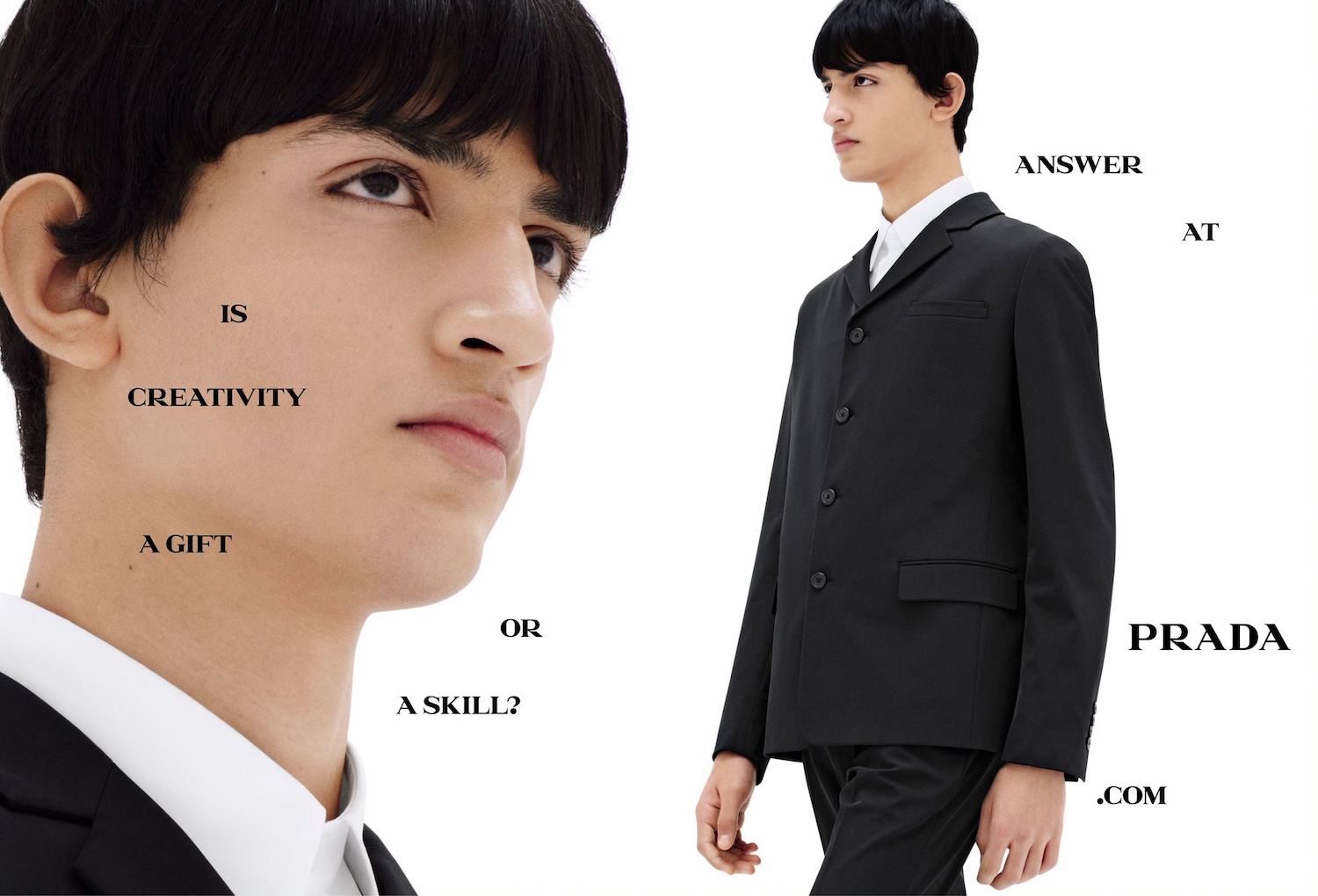

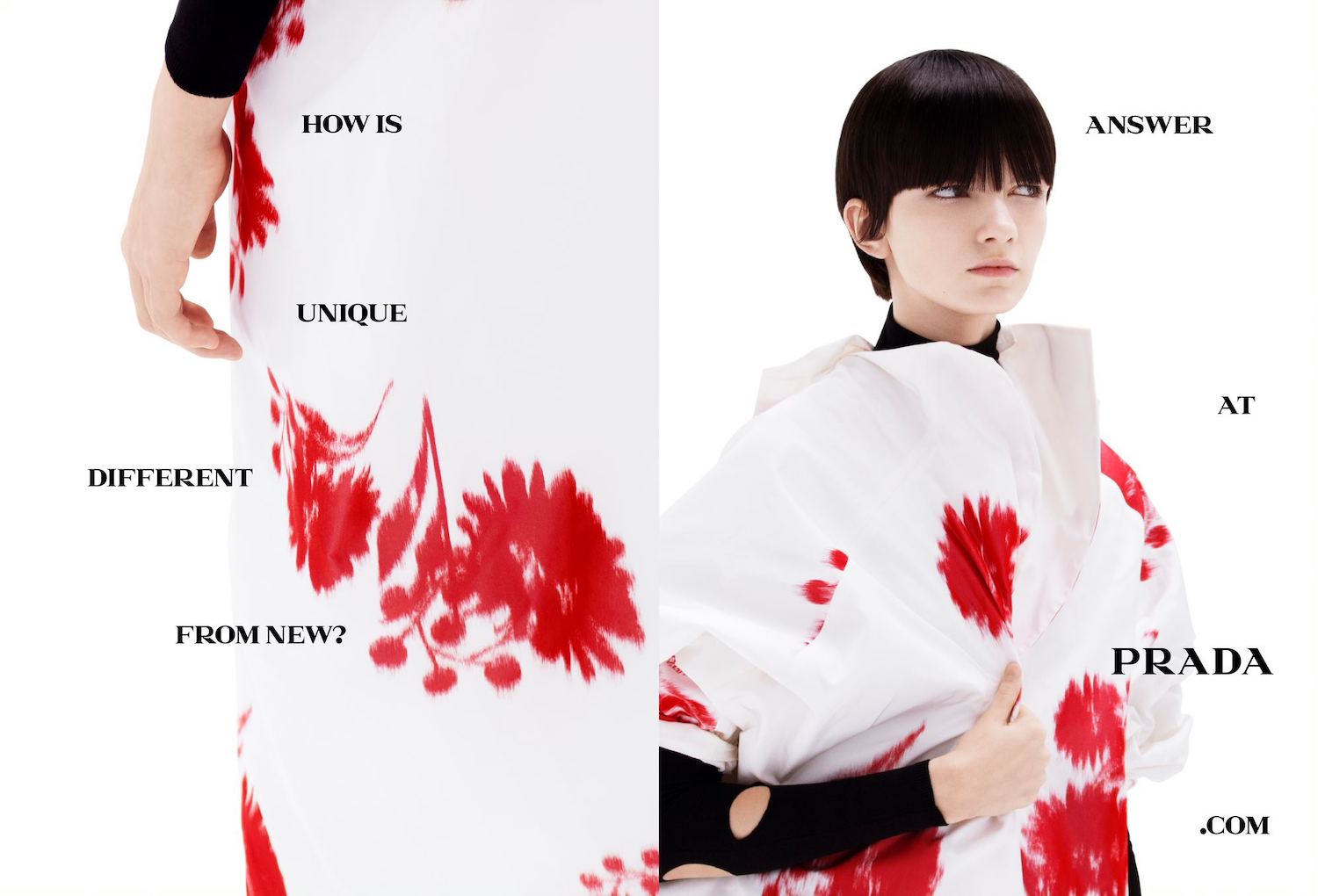

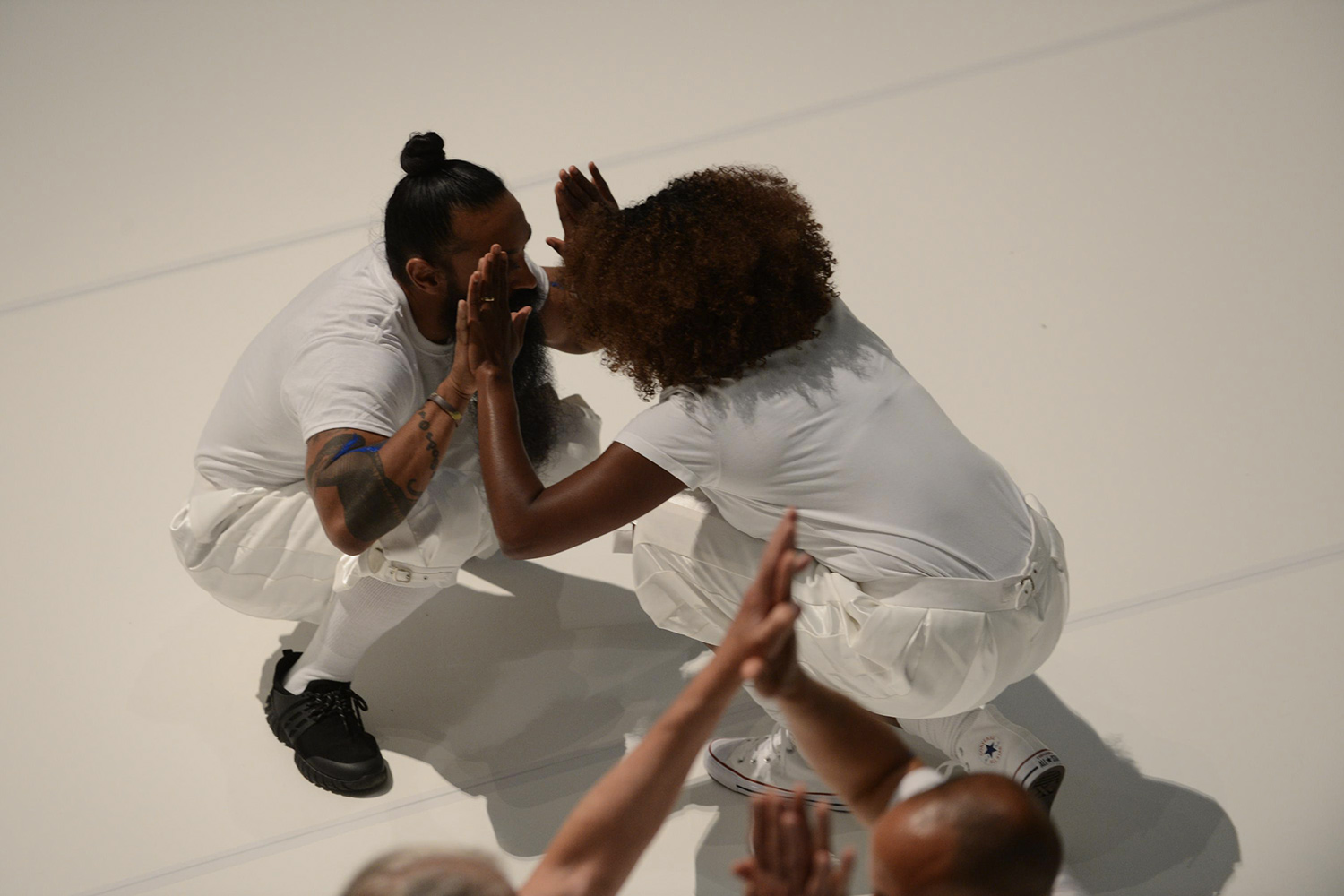

During the show, which was hosted on Instagram on September 24, the name of each model was written in Prada’s custom serif font on floating screens, surrounded by nests of cameras, tracking their walks. It was held, without an audience of course, in a thick-carpeted room, with floor-to-ceiling curtains and concrete pillars, all in primrose yellow. The clothes were beautiful, of course, and reticent, with a sense of elegance, purpose, and silence. Most looks were monochrome, black, white, or cream, with swirling patterns drained of their “trippiness,” and polka dots cut into the garments, a gesture at transparency and paradox. Prints from Peter De Potter appeared as abstracted instructions, and the Prada triangle, rarely used more prominently, appeared less as logo and more as a stamp of officiation. A comment from @NinaNoirPaints reads, “Looks like 60s minimalism has a heavy vibe here, along with 90s. Really, the whole big brother thing… Yeah we know we are DEFINITELY slaves to the technocrats. Love to watch the rituals of fashion foreshadowing what’s really coming. Worked in the industry for 20 yrs, there is sooooo much more to these shows, you have NO idea.” After, during a Q&A session with Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons, both designers spoke about uniforms and their love affair with them. Both described their personal uniform — black Prada pants and a white shirt for Raf, a white pleated cotton skirt and a blue sweater for Miuccia.

Uniformity extends beyond clothing. Uniformity is sameness. Uniformity is legibility. Uniformity is what all complex systems require, from the state in the form of the sort of bureaucracy I was obliged to complete on arrival to Berlin, to finance capital through the process of securitization.

The Kreuzberg Rathaus required not only that my profession fit into a prescribed category, but also my dwelling. The first time I went, with unsteady German, I stumbled explaining that although my apartment had a basement, it was indeed a first-floor flat. The universe of possibilities contained within each of us, and our limitless archive of past potentialities, right down to our exact dwelling, is of active hindrance to the smooth reading of a system. This is one reason bureaucracies have been so vehemently criticized for so long — Kafka! Weber! Thatcher! — especially when we consider the power accorded to a system as a function of this very process. Yet un-individualizing carries some blessings. On a recent trip to Italy, when regulations around travel shifted, me and my partner were required to take a COVID test on arrival at Milan Malpensa airport, booked via a portal on their website. This is what statecraft in the twenty-first century looks like — at least for those fortunate enough to inhabit the bodies considered able to navigate it. Nine inches of plastic inserting a swab into a tender region deep in your skull and an all clear emailed thirty-six hours later. The Prada factory in Valvigna, Tuscany, earned a reputation for its stringent anti-COVID measures, for what it’s worth, and I believe it’s worth a lot, with the Guido Canali–designed production facility encased in layers of clinical, rational modernity. Pathogens, like states, see populations, not people, and biosecurity depends on removing our individuations. There are three thousand workers at a factory. There are eighty thousand passengers arriving a day. What matters is not all those little stories each of us tell about our own safe practice and good health. What matters is the numbers of infected, and their names.

In 1903, Divisionist painter Angelo Morbelli represented Italy at the fifth Venice Biennale with six paintings called Il poema della vecchiaia (The Poem of Old Age). One hundred and fourteen years later, Fondazione Prada used the cycle as one of the centers of its 2017 Venice Biennale show “The Boat Is Leaking. The Captain Lied.” The pictures, in which light is suggested, a membrane of memory rather than depiction, as Aurora Scotti writes in the catalogue, show the elderly of Milan in municipal sitting rooms and soup-kitchen canteens. Morbelli’s luminously beautiful works often show workers or the destitute in their institutions of care: deserted, plain churches, hostels, and hospices, the building blocks of the twentieth-century welfare state. His sitters are almost always uniformly dressed, in the colors of anonymization, of anti-adornment: beige, black, and white. The plainness of his walls and sameness of the furniture are a kind of care, a respite, a moment in which the wretched receive an accordance of dignity.

Bureaucracy is a form of beauty and blankness a form of care: I think here of On Kawara, of Mierle Laderman Ukeles, of modernist public housing, of the scenes of Ian Curtis at work in the Macclesfield Unemployment Office in Anton Corbijn’s Control, of Michael Asher’s tearing down of walls between galleries and offices. I also think of Rationalist architecture, a decidedly unbeautiful side of the project.

Palazzo Gualino was built in Turin in 1931 as the perfect model of an efficient office building. Its designer, Giuseppe Pagano, was a critic, editor, and thinker. He was also a member of Italy’s fascist party and its mystical order, who renounced both in 1942. After fighting with the partisans, he was arrested by the Nazis and died in Mauthausen concentration camp from pneumonia, a sad, sordid rhyme with today’s plague. Yet his work provides a form of aestheticizing logic and sameness. The seven-story block looks like the platonic ideal of a local municipal office, squat and beige, radical at the time and now staggering in its ordinariness. You can almost hear the clack of heels on linoleum and the beep of your number coming up. This was a period which saw the state ruled not by the overt idealism of Pagano’s time, but the pen-pushers of liberal social democracy: a system which, at best, offered its citizens a measure of economic dignity and political stability in exchange for paying taxes and filling out the sort of forms that the Bürgeramt in Kreuzberg still runs on. Public duty was a virtue, quietly — for this was a system that took on, as a matter of urgency, the aesthetic mode of blankness.

Raf Simons and Miuccia Prada are fashion’s chief romantics of this post-1945 order, despite (because!) of their modernist revulsion for nostalgia. In both of their work, the twentieth century, and its collective dreams, looms large.

Miuccia’s past as a volunteer for the Italian Communist party is much vaunted, as is her rehabilitation of so-called ugly fabrics or clothes. All dovetail with a notion of a collectivity, of course — there is nothing inherently ugly about nylon and PVC, unless one counts the public as ugly, which, of course, many still do. Raf’s long engagement with youth tribes is similarly well-trodden — but the interesting thing here is not that he adores musical subcultures, but is obsessed with the reticence and elegance of them. In his collections, one never feels as though he is staring at the rock star. Rather, he is interested in the person in the crowd — the awkward youth to the left of the frame, the member of the tribe, shot at that liminal point before they grew out of gabber, or punk, or Joy Division and got real. Here we see a view on the citizen, not the demagogue. Rather it is the dutiful and the quiet at the center — the Isolated Hero, to quote the title of his street-cast monograph, released in 1999. Just two years later, Prada Sport’s spring/summer 2001 campaign advertisements focused on collective calisthenics, with dozens of models performing the literal movements of a citizenry.

Toward the end of The Utopia of Rules, David Graeber’s wonderful collection of essays on bureaucracy, he talks about the growth of fantasy as a genre. It arises, he claims, in highly ordered, bureaucratic societies: the more we have to fill out forms, the more we re-create the past as full of dragons. Orcs and elves never had to fuss with registering at town halls, after all. The reverse is surely true, and it is natural that the vast, undulating chaos of our present moment would make us look back at the steady state embodied by that very town hall, nostalgic for the sense of calm order and measured security. Prada’s SS21 show, to me, addressed this energy and provided a uniform for its reimagining, just as our age invites a reimagining of the public order. This is a dream of a moment in which we are no more or less than our names. When we are, quietly, enough. It was, and will be, once more.