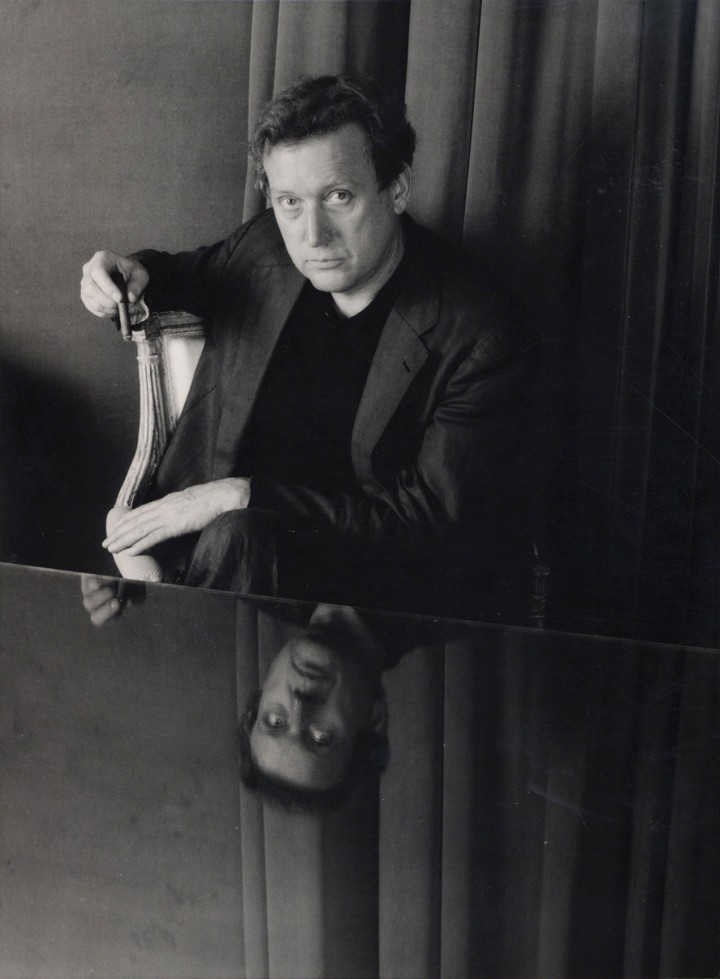

Donatien Grau: What was your background when you founded your gallery?

Michael Werner: I come from a lower middle-class context and was raised after the war, in the Ruhr. I was not good at school, but I met an art teacher, with whom I spent a lot of time. He also worked as an independent artist, and he used to tell me stories from his time at the art academy in Düsseldorf. I was fascinated with art, and I started to try creating art myself. But I was not good either. Then, I found an issue of a Swiss magazine called Du about the European art market. I discovered that there were only six or seven major galleries dealing with contemporary art throughout Germany. So I wrote a letter to a Berlin gallerist called Rudolf Springer, and I offered to work with him. He invited me to join him in Berlin.

DG: In Berlin, you had a very important encounter: Georg Baselitz.

MW: While working with Springer, I met an artist called Eugen Schönebeck, who introduced me to Georg Baselitz. After two years working with Springer, he threw me out and I was left with no option. Baselitz advised me to open my own gallery, which I did, with another person named Katz. So we opened the gallery Werner-Katz in Berlin, with an exhibition of his, where we showed Die Grosse Nacht im Eimer, which ended up being a considerable scandal. Then, Katz’s family took the money away, and I was left with no gallery — again. I talked with Baselitz and he told me I should open a new gallery: we opened with his “Orthodox Salon.” Back then, in Berlin, we could not sell a single artwork. I decided to move to Cologne and open a gallery there. I left with a few works by Baselitz, Lüpertz and Penck.

DG: You worked extensively with the same artists.

MW: It all relates to my biography, and to the events of my life. In Berlin, I also met A.R. Penck and Markus Lüpertz, through different channels. They were all different, and when someone started to call them the Neue Wilden and say it was a movement, I disagreed, but it is true that they, with Jörg Immendorff and Antonius Höckelmann, shared a common sensibility. It has always puzzled me that, for five hundred years of art history, we had only one international artist: Albrecht Dürer. Therefore, I understood that I needed to adopt an international approach to help their work to be acknowledged. Then I also worked with other artists that gave the gallery an international impact: Daniel Buren early on, Niele Toroni, and I had lasting collaborations with Marcel Broodthaers and James Lee Byars.

DG: You are often associated with the traditional formats of painting and sculpture. Would you agree with that?

MW: It is true that I personally like painting: the smell of it, the aspect of it, the feeling of being in a studio with a painter. And, as such, the anti-man, to me, is Marcel Duchamp. I had long conversations with James Lee Byars about Duchamp. But whatever he said, at the end, painting is still here.

DG: But you worked with conceptual figures such as Toroni or Broodthaers?

MW: Yes, but in their work, there is an intense idea of game. They play with the formats they use, and that is very important.

DG: The idea of writing history seems to be important for you. You have worked with contemporary artists, but also in the secondary market. What is the relation between both sides of your work?

MW: The first artist I was fascinated by was Paul Cézanne. And I have always been amazed to see that so many fascinating artists had been forgotten, or are not acknowledged as much as they should be. Etienne Martin, for instance, should be considered to be the French Beuys! I think that what we do forwards with contemporary artists can be done backwards with artists from previous generations.

DG: You then opened a gallery in New York. Why? Who were you working with then?

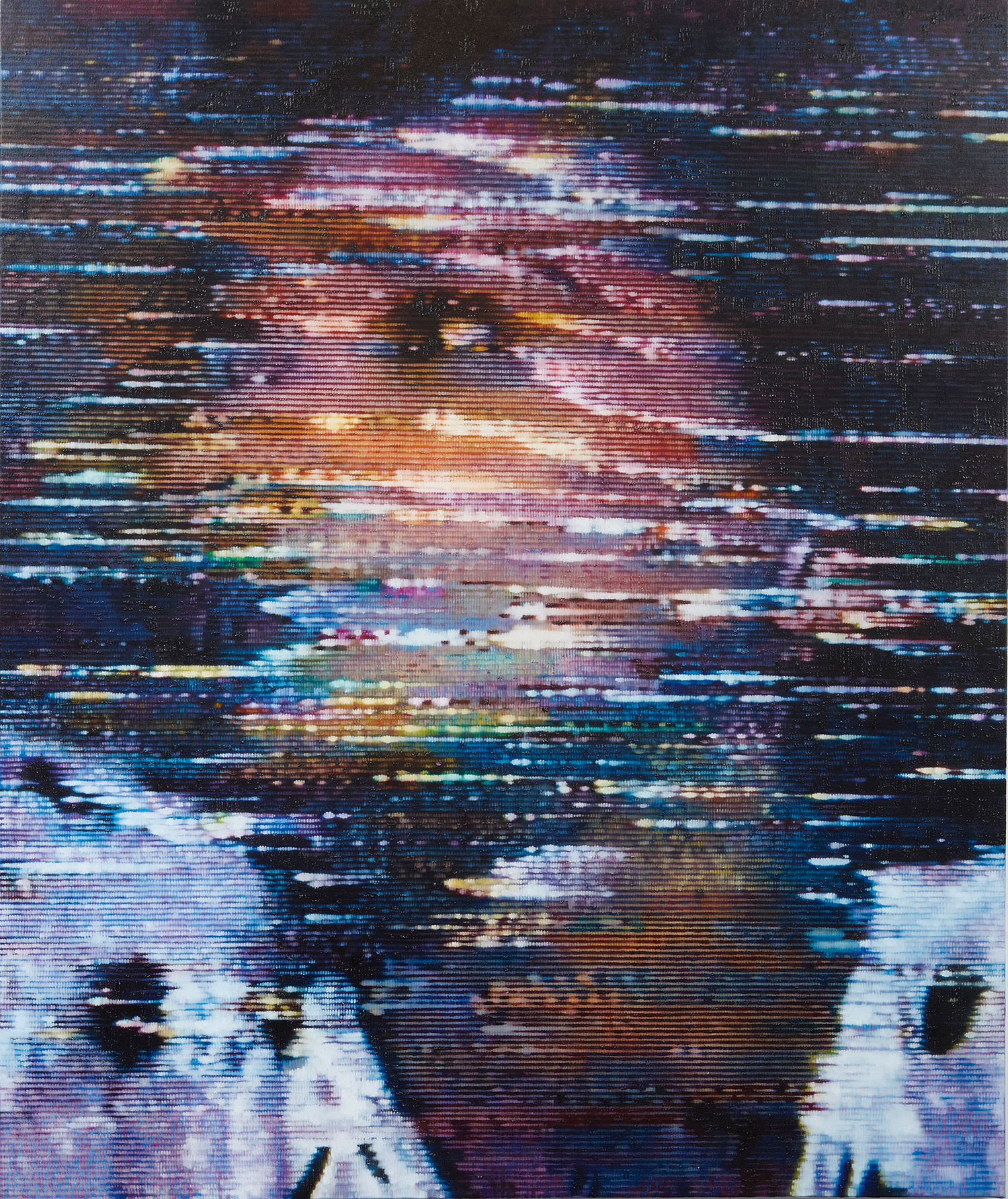

MW: In the early ’80s I met Mary Boone, who became my wife. I thought that all my artists should be represented by her, in New York, and that it would give them an international impact, after the exhibition curated by Christos Joachimides and Norman Rosenthal, “A New Spirit in Painting.” Most of them were already represented in the United States, but the idea was to solidify the representation. I did a few exhibitions of American artists in Cologne, such as Brice Marden. Today, I still have a gallery in New York, with its own program. It is a partnership with Gordon VeneKlasen, and has notably featured Peter Doig and Thomas Houseago.

DG: In September 2012, you are donating a major ensemble from your collection to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris: thirty-two works by Markus Lüpertz, thirty-six by A.R. Penck, twelve by Jörg Immendorff, fifteen by Per Kirkeby… What lead to this donation?

MW: It all comes back to a trip I did to Paris, with Baselitz, in the early 1960s. I remember walking inside of this museum and having a feeling of peace and fulfillment. Today, I am paying a tribute to this feeling. Of course, it is going to change the structure of the museum collections. But the donation, as my own collection, is a testimony of my life.