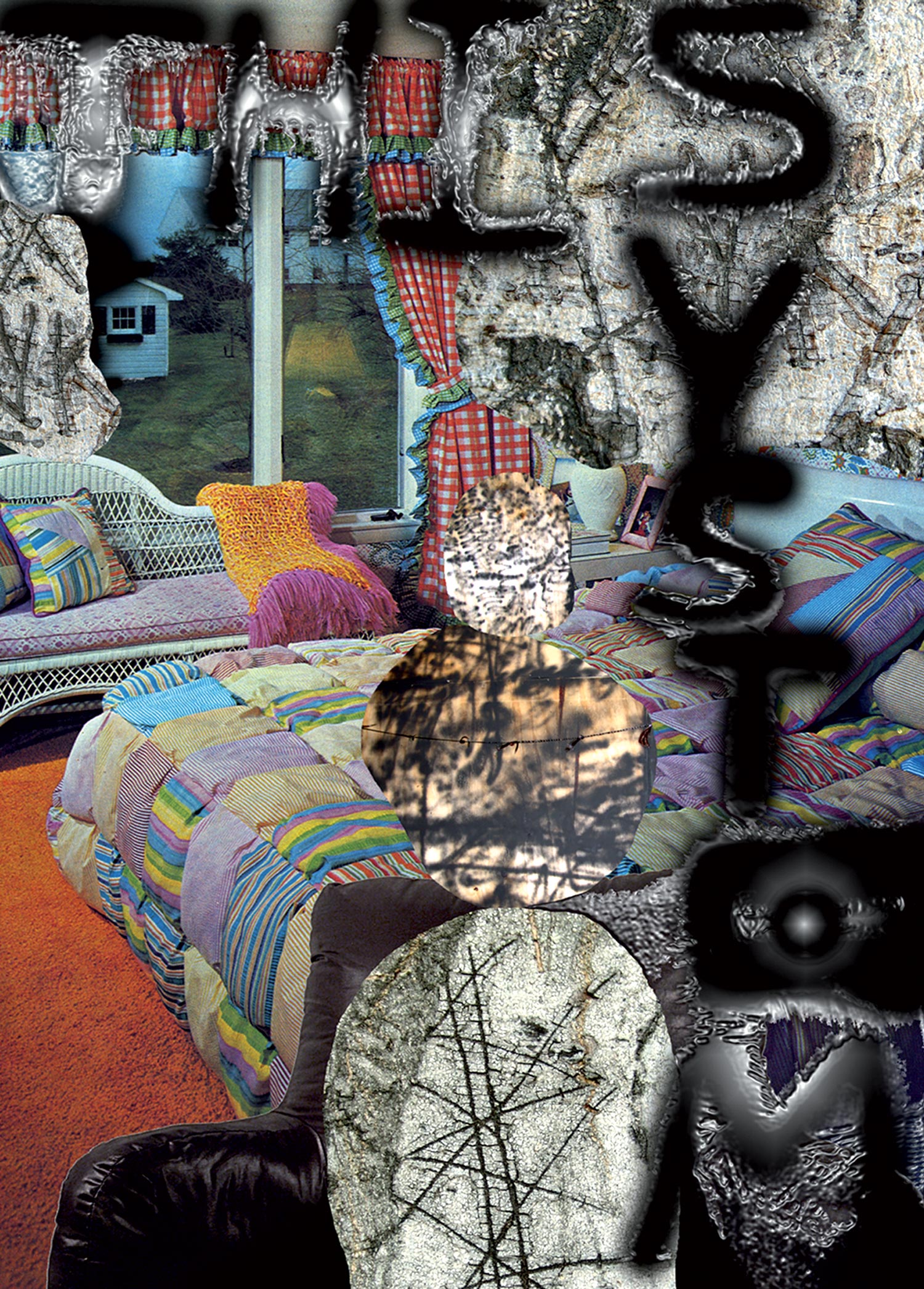

Michaël Borremans’ star is rising steadily. The artist first made a name for himself with drawings of very detailed stage settings allowing the viewer to glimpse into surreal scenarios that evoke the reality of an artificial theater. That is the essence of Borremans’ art: tempting worlds situated somewhere very distant from our daily reality.

Luk Lambrecht: Your work is not particularly ‘Belgian.’ Could you briefly sum up how your art evolved? How did you come to use this imagery?

Michaël Borremans: I think my work actually does have a particular Belgian touch: it could have been created only in Belgium. The context we live in, the contrasts, the ubiquitous absurdity — all have decisively contributed to my worldview. On the other hand, I also believe that there is something universal in my images. That is because I use clichés and other elements that are part of a collective consciousness. These elements are easy to recognize — my work would be perfect on biscuit tins.

LL: Your work reminds me of the concept of thought models. It quite often seems related to the early sculptures by the German artist Thomas Schütte.

MB: Yes, I feel a certain affinity with artists like Schütte. My drawings and paintings are thought models in the sense that I create two-dimensional modules that are situated on the border between the recognizable reality and the open possibilities our imagination allows. My works are sort of intimate rooms in which “big worlds” happen.

LL: But do you usually depart from reality, from existing photographs you find in newspapers and magazines, from your broad knowledge of the history of art?

MB: I start with existing images that seem interesting to me. Sometimes these images are indeed photographs from a distant past. I attempt to create an atmosphere outside time, a space where time has been cancelled.

LL: You once said that even today art should be able to seduce us. Isn’t that a point of view out of touch with the spirit of this day and age?

MB: The seductive element is quite important in my work. A work of art should be appealing, because, obviously, I want the public at least to look at the work. A multi-layered interpretation and appreciation is essential, but in my view the element of temptation comes first and is fundamental.

LL: Does the iconography of your work conspicuously refer to the theater?

MB: I proceed from the act of drawing itself, which, in my view, precedes deliberate judgement — the act of drawing generates thinking. I like to draw from a certain distance. From my detached perspective, I create a composition with figures, heads, puppets and marionettes. I position them on a sort of stage, a platform or simply on boards. Sometimes I create a black background, which evokes the black cube of the theater, i.e., the darkness from which the public undergoes the different scenes.

LL: Does that allow you to create a certain distance in your work?

MB: That distance is a prerequisite, since what I depict is an autonomous reality. I want to make the divide with that which we call reality very clear. That is the principal reason why I have chosen to opt for painting as a medium. A painting always represents an autonomous space. The painting is beyond suspicion; it is an instrument of the imagination and — at least in our times — does not aspire to document anything.

LL: Do you scribble notes on your drawings?

MB: As I said, for me writing and drawing originate from the same gesture. These notes you may see in my drawings can be about anything — they may even be telephone numbers I have jotted down. For me thinking while drawing is like taking a mental walk on the border that separates thought and action. Action, for that matter, i.e., making a drawing or painting, is sometimes quite a tough job…

LL: Painting is quite fashionable today. Do you see a particular reason for this phenomenon?

MB: You know, today you can just juxtapose anything. That is what makes our present time so interesting — everything is possible. There is a huge variety of media that function well when combined. In all disciplines we see an explicit culture of sampling. That explains the new interest in painting in the visual arts: painting is a clichéd medium that allows the use of a wide range of materials and an almost endless profusion of references. What I do with painting is unprecedented. I am a true avant-garde artist!

LL: Do you think you could express your imagination through the more refined technique of Photoshop?

MB: With Photoshop you miss this incredible power of the tactility of the original painting. That is precisely what in my view constitutes the ultimate temptation of paint on canvas.

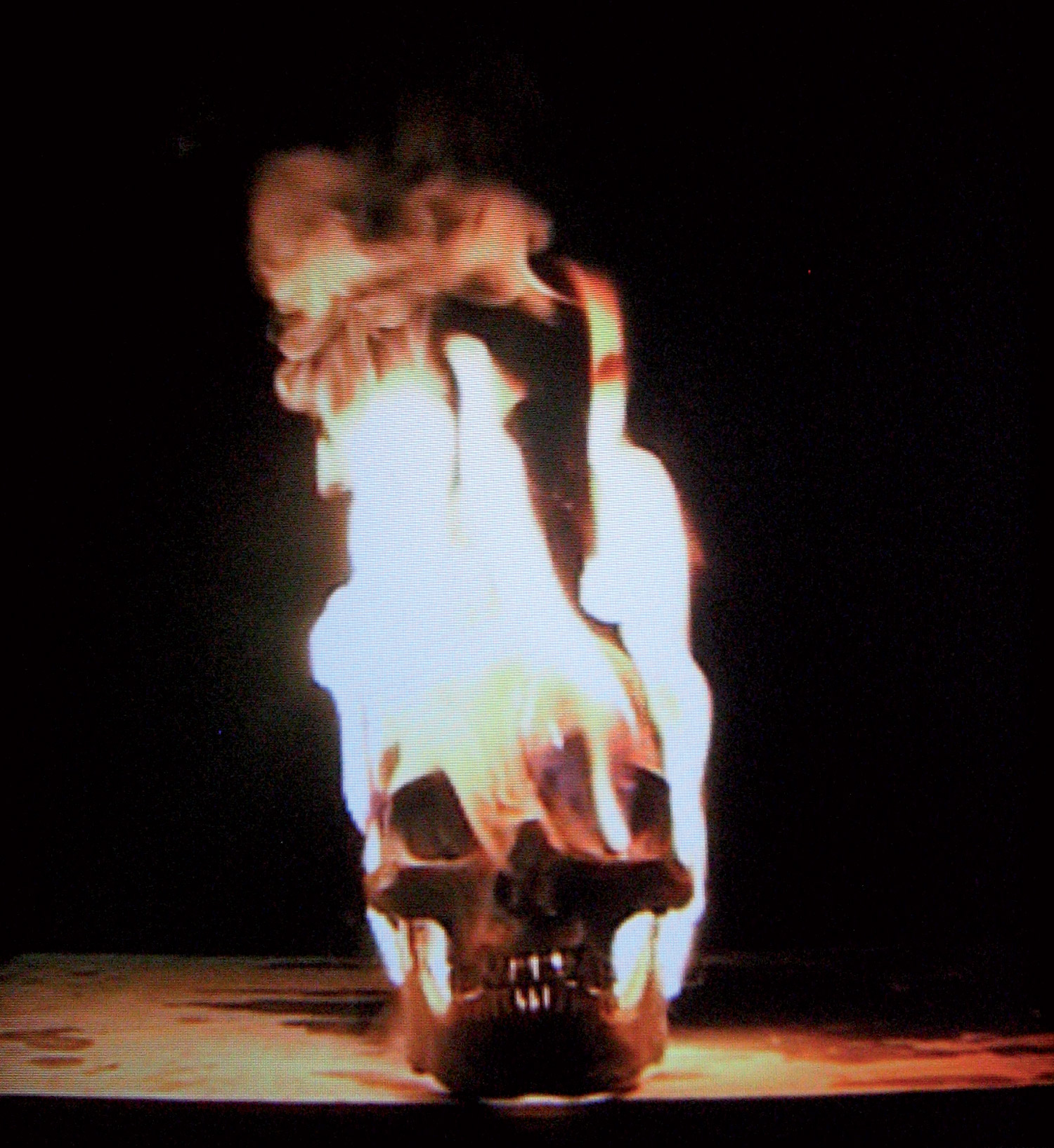

LL: Yet at this year’s Berlin Biennale you showed a video?

MB: That work was actually a film that afterwards had been transferred to DVD. The film was presented on a small LCD screen I had framed like a painting. The original film had been produced by a professional filmmaker. It was based on a drawing from 2002 which I reproduced in three dimensions. The film contains a lot of abstract shots of a girl who slowly spins round in front of the camera. For the film, we had used an old Bolex camera with a special lens. We used film because there are particular shades of colors and shadows that are impossible to achieve with video. Film, as a medium, is in fact very close to painting, much more so than photography.

LL: Do you intend to make more films?

MB: Yes, but making a film is expensive and time-consuming. Some museums have expressed an interest. Then again, to make a film you work with a team. That involves compromises that as a painter you don’t have to make…

LL: On one of your works reads “La société n’existe pas” [The society doesn’t exist]. Can you say why?

MB: In this work the imaginary world only exists in the space or room represented. That room is the continuation of the paper on which I have drawn. My art is not about society or sociology. Like the modernists, I attempt to create a sort of utopia inside an atopia. My drawings and paintings are thought models inside which certain rules and laws apply that are not necessarily valid in the reality we are familiar with.

LL: Your works sell very well these days, don’t they?

MB: A lot of money is spent on art nowadays. The high prices may raise eyebrows, but I think it is quite interesting that art is highly valued by society. The level of civilization of a society can be measured through its esteem of art. In this respect our society is not in decline.

LL: Which artists have been important for you?

MB: Despite what I’ve said, I like many videos. I like the strange videos by the Finnish artist Eija-Liisa Ahtila, the work of Jesper Just and Olaf Breuning. I also like the Americans Robert Gober and David Hammons. But to some extent, everything you encounter as an artist has some relevance to your work. You absorb everything and you spit it out again, in a peculiar, authentic manner.

LL: Your works often quite explicitly refer to art in public places. Do you have any plan to realize projects in public spaces?

MB: Actually, I’m too timid to intervene in public places. That would require a great deal of attentiveness and respect. And there is too little of that: it’s all about commerce. Because of that, the visual pollution is getting out of hand. For the time being, I prefer to put things on paper. The effect of artworks in public spaces is often rather silly. And there is never sufficient money… An exception I think is Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Monument in Berlin. But if there is the willingness to invest in a work of art in public or a monument, I would consider the project.