At the 5th Berlin Biennial, Melvin Moti showed his recent film E.S.P. (2007) at the Neue Nationalgalerie together with a photograph and a sculpture consisting of a soap bubble mysteriously floating, as a permanent presence, in a glass bottle (E.S.P. – In the face of forever, we’re just getting started, 2008).

The work Moti has produced since about 2001 has included interventions, installations, publications, films and videos. His early videos are primarily based on documentary footage, such as Stories from Surinam (2002) and Texas HonkyTonkin’ (2003): loosely knitted testimonies of the history of the Indian plantation workers in Surinam, where the artist’s own roots lie, and of the (little known) black origins of country music in Texas. perhaps his most celebrated ventures are four films: No Show (2004), The Black Room (2005), E.S.P. (2007) and The Prisoner’s Cinema (2008). They are comparably structured in presenting extremely reduced, almost abstract images, accompanied by a compelling soundtrack: a scripted monologue or a fictional interview, to which the image slowly and inexorably attaches itself. Moti often seeks collaboration with scientists to contextualize his artistic output through essays and talks. Although his work may differ in terms of form, it can always be connected to the artist’s interest in the mechanisms of history, in relation to the processes of remembrance and imagination. Moreover, in his recent film work he focuses on psychological experiments and paranormal phenomena, like out-of-body experiences, hallucinations, hypnosis and Surrealist ‘sleep-writing.’

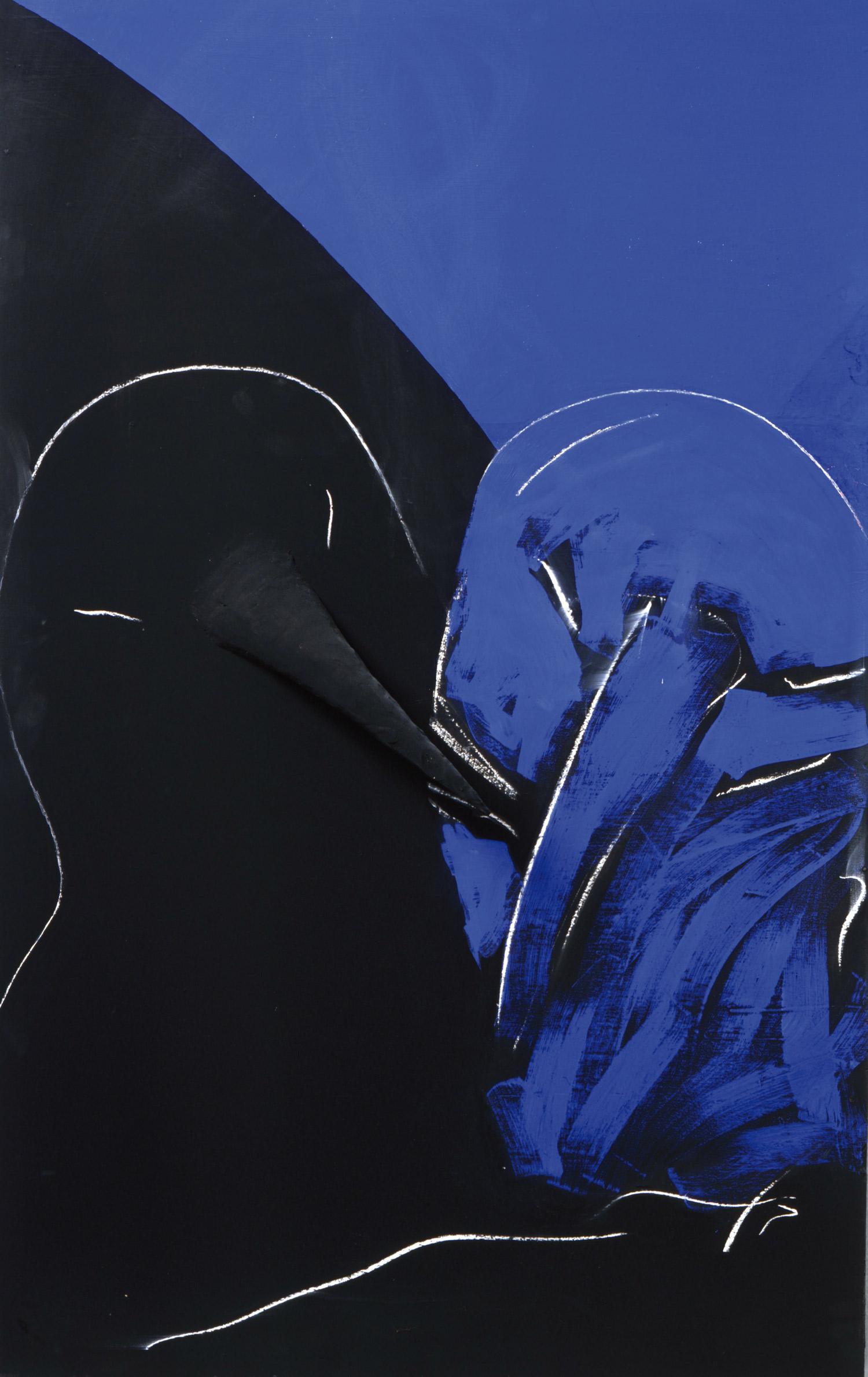

The 35mm film E.S.P. combines exceptionally slow, hypnotic images of a bursting soap bubble with the story of the dream logs kept by John William Dunne (1875-1949), who possessed precognitive powers. At the age of 18 Dunne discovered that fragments of his future were appearing in his dreams (in 1927 he published a book entitled An Experiment with Time, in which he describes his dreams in which past, present and future occurred simultaneously).

In a monologue written by Moti, a male voice talks in the first person about Dunne’s experiences. It is a narrative concerning human consciousness, the experience of time, speed, and the pursuit of an impossible goal: the ability to see into the future.

The Prisoner’s Cinema, Moti’s latest work, premiered this spring at the FRAC Champagne-Ardenne in Rheims. The 35mm film shows an image of light shining through a rose window. As the viewer looks at this abstract light projection, geometric patterns slowly take shape. The title refers to phenomena that are recognized in neuro and optical science as hallucinations occurring in response to prolonged visual deprivation. Prisoners, confined in dark cells, seem to have repeatedly reported these apparitions. Again, the geometrical image strangely resonates with the spoken narrative, in this case the voice of a female scientist who gives a rather deadpan description of the geometrical patterns.

It is amazing to see how Moti is able to unearth forgotten and sometimes obscure material in his research on human consciousness, the visionary and imagination and bring it to life in daringly experimental combinations of sound and image. Undoubtedly, there will be more surprises to come in this project of cataloguing the musings of the mind.