The history of art in India dates back to a variety of mediums, from the renowned Ajanta Cave paintings to the various schools of sculpture and miniature painting. Further prominence was achieved by the representatives of the Company School, by Raja Ravi Varma (nineteenth century) and pre-independence artists such as Jamini Roy and Amrita Sher-Gil (early twentieth century). Colonial repression led to India’s independence in 1947, followed by political unrest and the partitioning of India and Pakistan, which affected families, socio-political systems and everyday personal relations, which in turn lead to art made in response. During this period all Western influences were ruled out and replaced by a strong sense of nationalism, which was seen particularly in the Bengal School (Eastern India). This school of art drew inspiration from traditional art forms. As a stark reaction to the Bengal School, a group of six revolutionary artists (F.N. Souza, S.H. Raza, M.F. Husain, K.H. Ara, S.K. Bakre and H.A. Gada) formed the Progressive Artists’ Group in Bombay (Western India) in 1947. Raza stated that their art was “an enquiry into our values, our culture … and life itself.” These artists, along with their contemporaries such as Krishen Khanna, Akbar Padamsee and Tyeb Mehta, are considered India’s modern masters. They broke with the conventions and clichés of the colonial period to make way for newer and more experimental forms of art to emerge. A seminal court case that Padamsee won in 1954 — against the Vigilance Department of the CID for censorship of two paintings of nudes (Lovers I and Lovers II) — set a benchmark that today allows all artists to exhibit works on any subject matter in a gallery or private space, per an exemption to Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code.

The 1970s saw aesthetic developments that grew into more recognizable contemporary forms within the global context. The art of this period, which came to be referred to as “contemporary,” drew from global issues with an acceptance of India’s recent political history as a nation and with a more nuanced outlook regarding the notion of nationalism and Indian-ness. The Indian freedom movement became an important subject in art, and Gandhi was one of the most widely used images. Revisionist thinking in art toward the end of the twentieth century began to address more personal issues. Most of the art created during this period was weighted with associative meaning, and the visual layers could be deciphered only by studying a range of references that all lead back to the self. Understanding the origin of the artist’s ideas and research became imperative to understanding the work.

Nalini Malani, Bhupen Khakhar and Vivan Sundaram are a few artists who were path breakers in their use of media, concepts and representational codes. Along with younger figures such as Subodh Gupta, Bharti Kher, Atul Dodiya, Jitish Kallat, Sudarshan Shetty, Shilpa Gupta, Nikhil Chopra and their contemporaries, they are arguably India’s first generation of contemporary artists. In 2004, artist-curator Bose Krishnamachari introduced seventeen artists in “Bombay x 17,” an exhibition that traveled from Mumbai to Kerala. (Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu went on to establish India’s first biennial, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, in 2012.) With the boom of the art market globally in 2006, many of these artists gained international recognition, and India became established on the global contemporary art scene.

The younger generation of Indian artists drew from their peers but also moved away from larger issues, preferring personal issues in the service of a more intimate dialogue with their audience. Exploring this new aesthetic, they began to use media in a relational manner that some saw as a new genre of art.

During the 1990s there was an influx of mass media in India, with television channels multiplying and the Internet making its presence felt widely. Artists began to move away from traditional forms and to experiment with new media; what once had a certain technological novelty has over the past two decades slipped into the subconscious of the everyday. This integration has fostered a shift away from a focus on material and instead toward an understanding of media as a tool for communicating concepts.

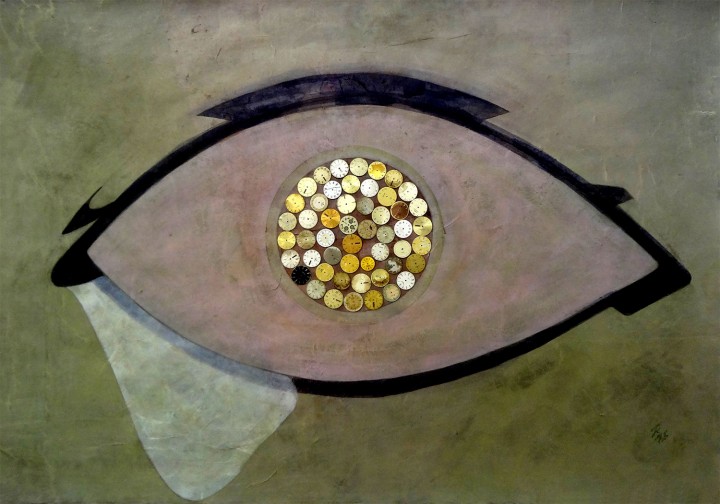

The Internet, still a huge source of images and information, has also become a tool for artists to address social concerns. For instance, Jaipur-based artist Nandan Ghiya’s on-going series DeFacebook posits a global social media community with a defaced past. Ghiya’s works reflect change as a constant spanning from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century, all within a single distorted frame.

Ghiya works with old photographs, images and found objects to transform them into three-dimensional download errors, glitches and pixelated images, in this way transposing the digital age with the aura of the old. The artist’s role as a teacher at the Fashion School in Jaipur merges with his views on art, design and the digital world; he sees terms such as upgrade and update as raw materials to render into a “contemporary” form. DeFacebook refers to these works as self-portraits of the artist as an outsider.

Though Ghiya works with a strong Indian cultural subtext, his works speak to a global audience familiar with old family albums, blue screens of digital malfunction, vandalism, anthropology and an uncomfortable recognition of alienation. There is a sense of the urgency of preserving the digital past. Sahej Rahal, on the other hand, draws detailed references from the past — including pre-historic man, as in Helix House (2012) — to create futuristic situations, time warps and fictitious narratives. He refers to his practice as a burgeoning meta-narrative that unfolds in the contemporary. It stems from history and references to human civilization, yet erupts into a futuristic fantasy with elements of the everyday. Found objects become part of the artist’s installations, sculptures and performances, carrying forward an embedded history and physicality.

Harbinger, presented at the 2014 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, comprised eight hundred sculptures that Rahal created from the river clay of the Periyar River. Ranging in size and subject — from agricultural tools to futuristic forms — these pieces inhabited an empty laboratory space. In Rahal’s work, it is the viewer who completes the work with their accompanying memories, fantasies and personal associations that render meaning.

The idea of actively engaging the viewer is something that was seen earlier, particularly in Shilpa Gupta’s works (Shadow Box series). Prabhakar Pachpute, in his work Canary in a Coalmine (2012), extended the concept of participation by making his viewers view the work in a dark room with a flashlight (similar to mine workers underground). Pachpute’s works directly reference the situations and environments of miners and laborers globally. The works reject the mundane through unconventional combinations of traditional media. Projections, sculptures and shadows accompany site-specific charcoal drawings in a charged, relational manner. In this way a new aesthetic evolves via the execution of traditional media within a new, more experiential context.

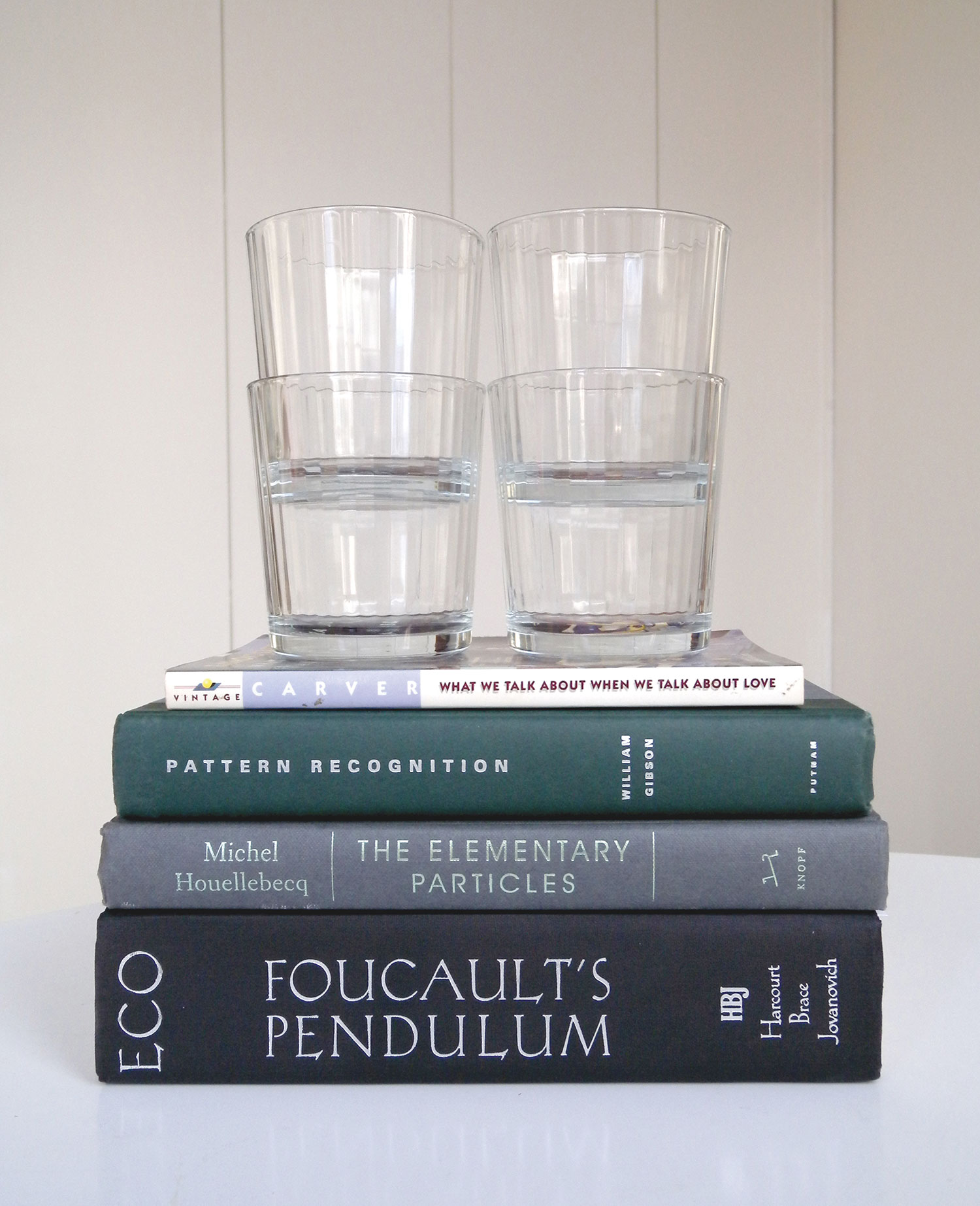

Tanmoy Samanta uses the conventional medium of painting to articulate a contemporary dialogue with the everyday. His canvases include painted books in which he becomes the storyteller, the cartographer and the bearer of tradition. Samanta’s minimal interference with the language of the medium renders a visual poetry suggestive of the Company and Bengal Schools of art. He refers to his carefully worked renderings of books and other somewhat banal forms as sculptural explorations. The boundaries between the real and the imagined become blurred, teasing the viewer into a “state of speculative uncertainty.” History and secrets are withheld in fragile depictions of solitary containers, cabinets and eggshells (The Cartographer’s Paradox, 2013). In a recent commission by a law firm to transform law books into art works, Samanta addressed the effect the law has on the mind of a layperson. Once again, a new aesthetic emerges by seeing the old in a renewed way whereby the boundaries of art forms collapse and coexist.

Similarly, Rathin Barman chooses to confront the environments we live in. Referring to the contemporary as an ever-changing phenomenon, he understands that what is relevant today will eventually fade tomorrow. Barman’s practice is based on engagements with local communities: conversations, field notes, written and oral histories become source material for visual transformations. His most recent project (No… I Remember It Well, 2015) is a response to socio-political issues related to landscape and architectural inhabitation, in turn raising questions about the notion of home, displacement and ownership of space. Communicative in nature, Barman’s works, which are interventions into the space they are displayed in (particularly the sculptural installations), actively involve the viewer’s participation.

Perceptions of and reactions to Barman’s work can hinge upon an audience member’s pre-determined ideas, social background and even nationality. Using mediums as narratives of change, his sculptures and drawings often include salvaged construction materials, including concrete, abandoned wood, bricks and rusted metal.

Mumbai-based artists Prajakta Potnis and Hemali Bhuta address similar concerns in their explorations of architecture and media. For Potnis, mundane objects and spaces become living organisms that carry the residues and living patterns of previous users and inhabitants. Working with highly accessible imagery, the artist attempts to bridge the aura of aloofness that can exemplify art in a gallery space. Her first site-specific work, White Lines Coming Home, created in Thane in 1999, raised questions about the role of contemporary art in her neighborhood. The spare subject matter in her photographs, drawings and sculptural installations belie a complexity and a subtle attention to detail. In The Curtain (2005) and Room Full of Rooms (2012), flooring, corners of rooms, windows and walls are witnesses of historical inhabitancy. Through their identities, they become the only connection to and separation from the intimate space of the individual and the world outside.

Hemali Bhuta, on the other hand, identifies past aspects of spaces and incorporates ephemeral objects into environments so that they seem to belong there. Embracing imperfection and disintegration, exploring states of uncertainty and situations of vulnerability, Bhuta connects her personal emotions to external landscapes, which are then translated into a visual language using materials that range from cloth and chalk to soap, graphite and cement.

In a works such as Slit (2012), the ephemeral nature of the work signifies the impermanence of situations and beings. For the viewer, the works feel more chanced upon than forced (such as Speed Breakers, 2012, at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park), playing with the idea of conscious visibility and invisibility in our surroundings. Bhuta works closely with her husband Shreyas Karle, and although their practices vary visually, their thought processes stem from similar discourses. In a nation where the idea of museums and art education is still growing, as in India, there is a need for more discursive spaces. The CONA Foundation, initiated by this artist couple, allows for various levels of engagement and discussion to exist in what Karle refers to as “voids left behind by the contemporary art system.”

In his own artistic practice, Karle denies associations with the notion of the contemporary, which he describes as something that has been influenced by external structures with very limited focal points. He too addresses the immediacy of his surroundings, which he recognizes as something one can always choose to add to or subtract from. Making references that are more generic than personal, his concerns primarily deal with the grammar of images, which, unlike language, allows for greater experimentation. Karle sees his use of this grammar not as a specific medium, but as an idea that allows for any given medium or discipline to enter his artistic practice. A work like Point of Fall (2015) conveys a sense of physical and psychological precarity that can be universally identified with.

Karle and his contemporaries insist on raising more questions than providing answers. Their works shift the viewer out of comfort zones to address issues that may be disturbing, sensitive or contradictory. Aspects of society and spaces become art forms in themselves, while elements from the past filter down through time to reflect a new contemporary. The languages these artists converse in might be considered highly individualistic, yet they all consistently communicate with their surroundings and audiences. Boundaries are dissolved while addressing global issues both private and public: marginalization, economic insecurity, urban existence and more. Through conversation, observation and creation, they engage in a language of tomorrow that connects with viewers today.