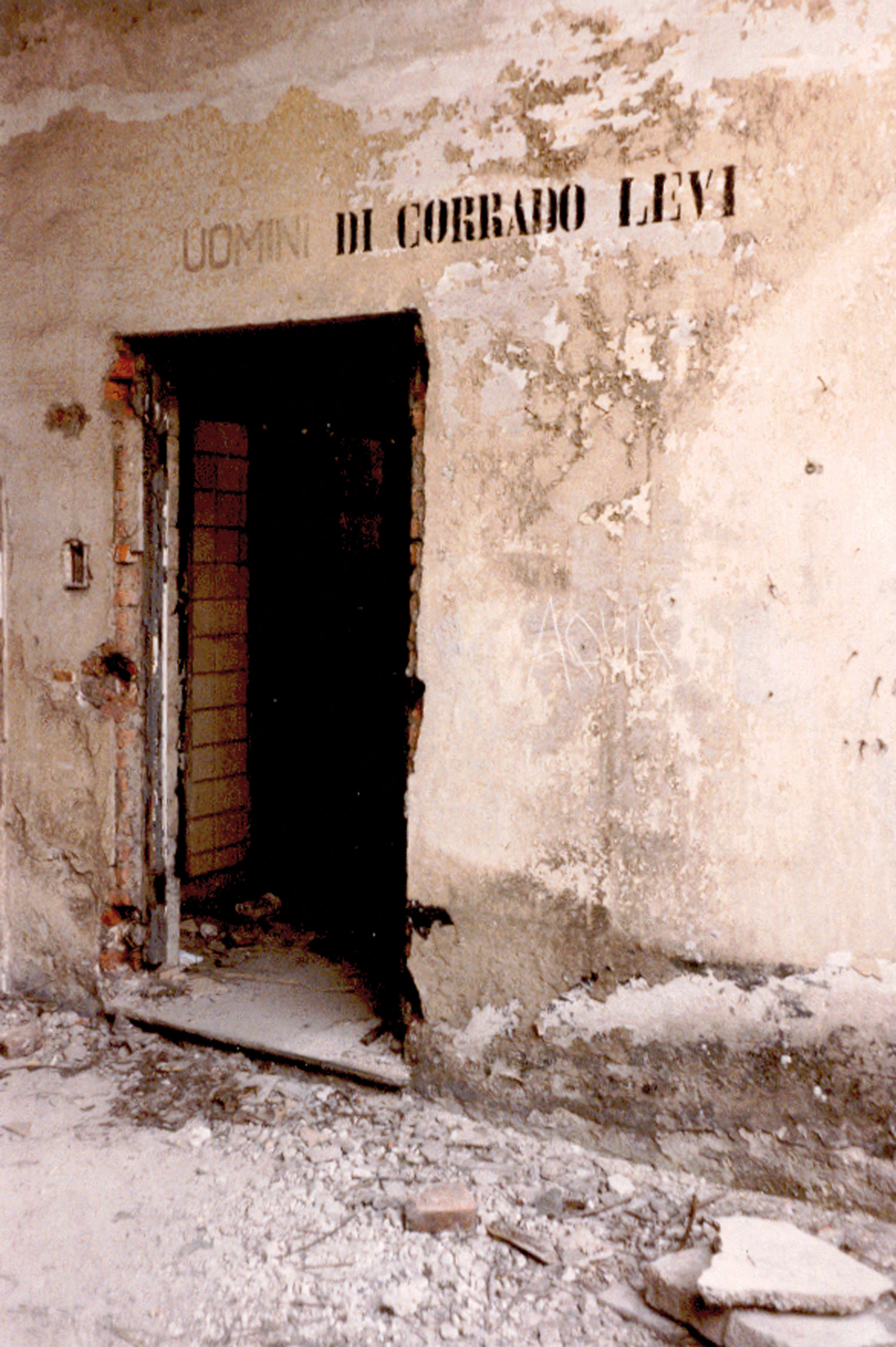

After an almost three-year break, during which he curated, along with Gioni and Subotnick, the 4th Berlin Biennial (a real masterpiece compared to the current one), Maurizio Cattelan has restarted intense creative activity. In 2007 he silently reappeared with new works at the MMK in Frankfurt, and he began 2008 with a solo show at the Kunsthaus in Bregenz. Three new works, with some appendices, focused on one issue: death.

This is a frequent issue for Maurizio Cattelan, who despite gaining fame for being a prankster, has always tackled deep issues; just think about the famous Bidibibodibiboo, the little suicidal squirrel in its small cheap kitchen. But now the persistent thought of death in Cattelan’s work is becoming austere. The exhibition is announced by a dramatic poster hung all over town, featuring a big “thumbs down” to a flaming Bregenz, like an advertisement for a disaster movie. The show is displayed vertically, in that each work occupies a floor of the museum. The first work looks like it was dedicated to life, featuring two stuffed labradors guarding a newborn chick. A strange family, a weird nativity, that reminds us that life is such a miraculous exception and so fragile, to be carefully preserved. On the second floor nine white sacks cover nine lying human bodies. How many scenes like this have we seen on TV? The aftermath of a massacre or an accident, with corpses lying on the ground waiting for identification. One falls into silent meditation.

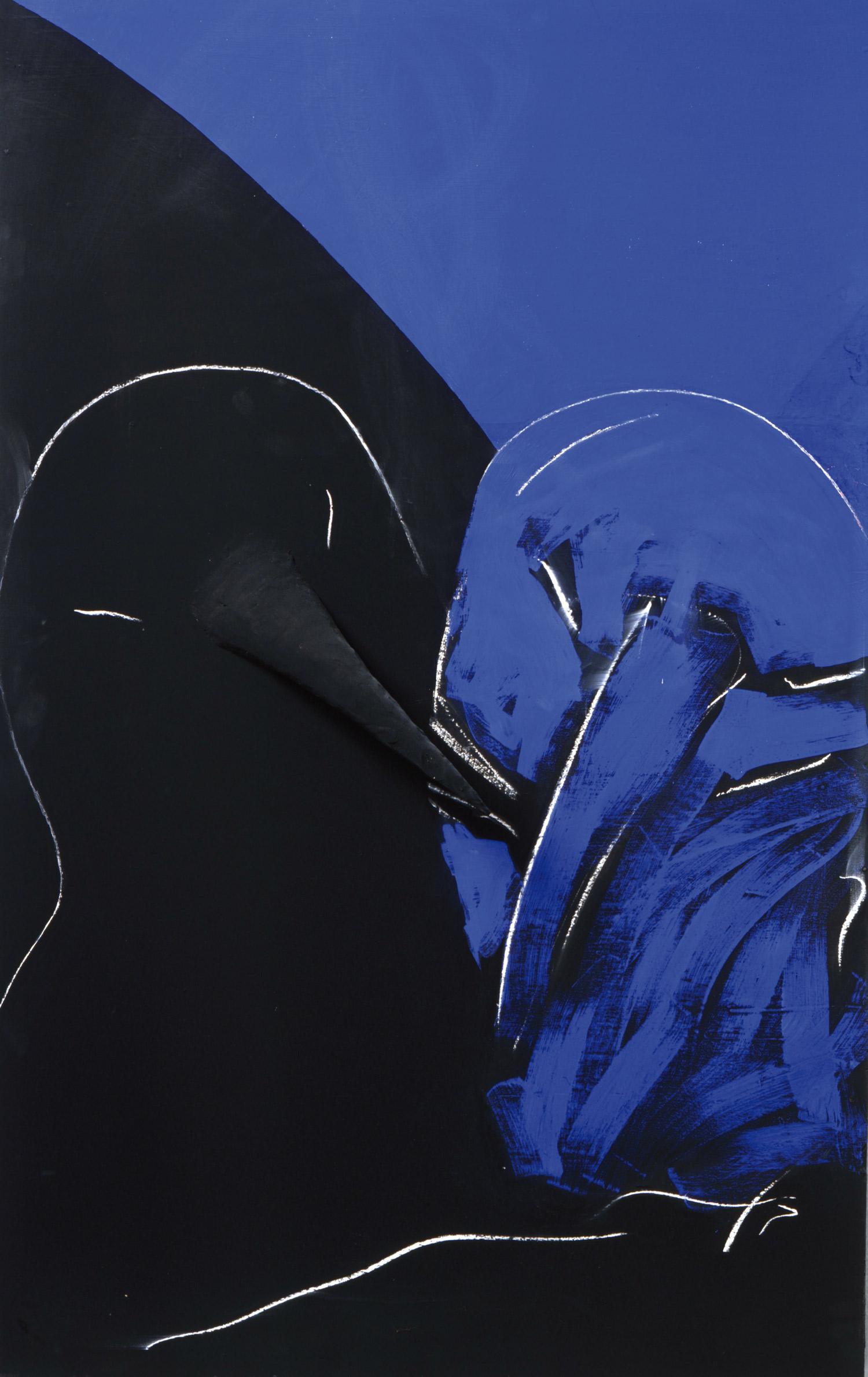

If there is no irony, there is still a surprise: the sculptures are made of white Carrara marble. Like Sammartino’s Veiled Christ in Naples, Cattelan recalls the great tradition of the statuesque, in which the body’s shape protrudes through draped fabric. The use of marble, dating back centuries in art history, makes this tragic scene all the more eternal. So the work becomes a silent requiem, a prayer of sorts for the whole of humankind.

At the top of the stairs that lead you to the 3rd floor, the door is closed-off by a girl in a nightshirt who is hanging by her hands from the doorframe. This female Crucifixion is almost an excess of spirituality, as if Cattelan wants to reach mystical levels. Ambiguity lies in the fact that the pose is lifted from a photograph by Francesca Woodman, who committed suicide in 1981: death as a life choice. Quoting her work, Cattelan not only exalts the sense of that photograph, but he also underlines the importance of what happened in Woodman’s life. That confident thief, always ready to steal from his neighbor and another artist’s experience, now risks living the apostle’s experience.

The current show is unexpectedly classical Cattelan. It seeks strong values. The journey is narrow and difficult, and it’s easy to be rhetorical: God, country and family. One could synthesize the excursus back into the show. The austerity with which the artist deals with the themes and the references to the history of art practice gives the lightness that in his previous works was achieved through irony. This might be the moment to start thinking about core values.