Matti Braun thinks big. And he’s looking at you. His interest lies in the cultural and artistic relationships that transgress traditional boundaries that separate people, regions and religions, with a particular interest in moments of misinterpretation or misrepresentation, that form the understanding of ideas for whole generations.

His latest venture has taken this to a new level: The Alien, based on a film script from 1967 by the famous Indian film director Satyajit Ray, that remained unrealized in spite of Columbia Pictures backing the project, and Hollywood greats Peter Sellers, Steve McQueen and Marlon Brando lining up to play the leading parts. In the script an extraterrestrial spaceship lands in a lotus pond close to a small village in Bengal. The arrival of the alien, who looks like a bizarre naked child, triggers a series of strange incidents and erratic plant growth. He befriends a small boy from the village, and plays tricks on the locals and mocks an American engineer, until he rather unexpectedly leaves again. Steven Spielberg’s immensely successful film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial appears to draw a lot of inspiration (however unacknowledged) from Ray’s script.

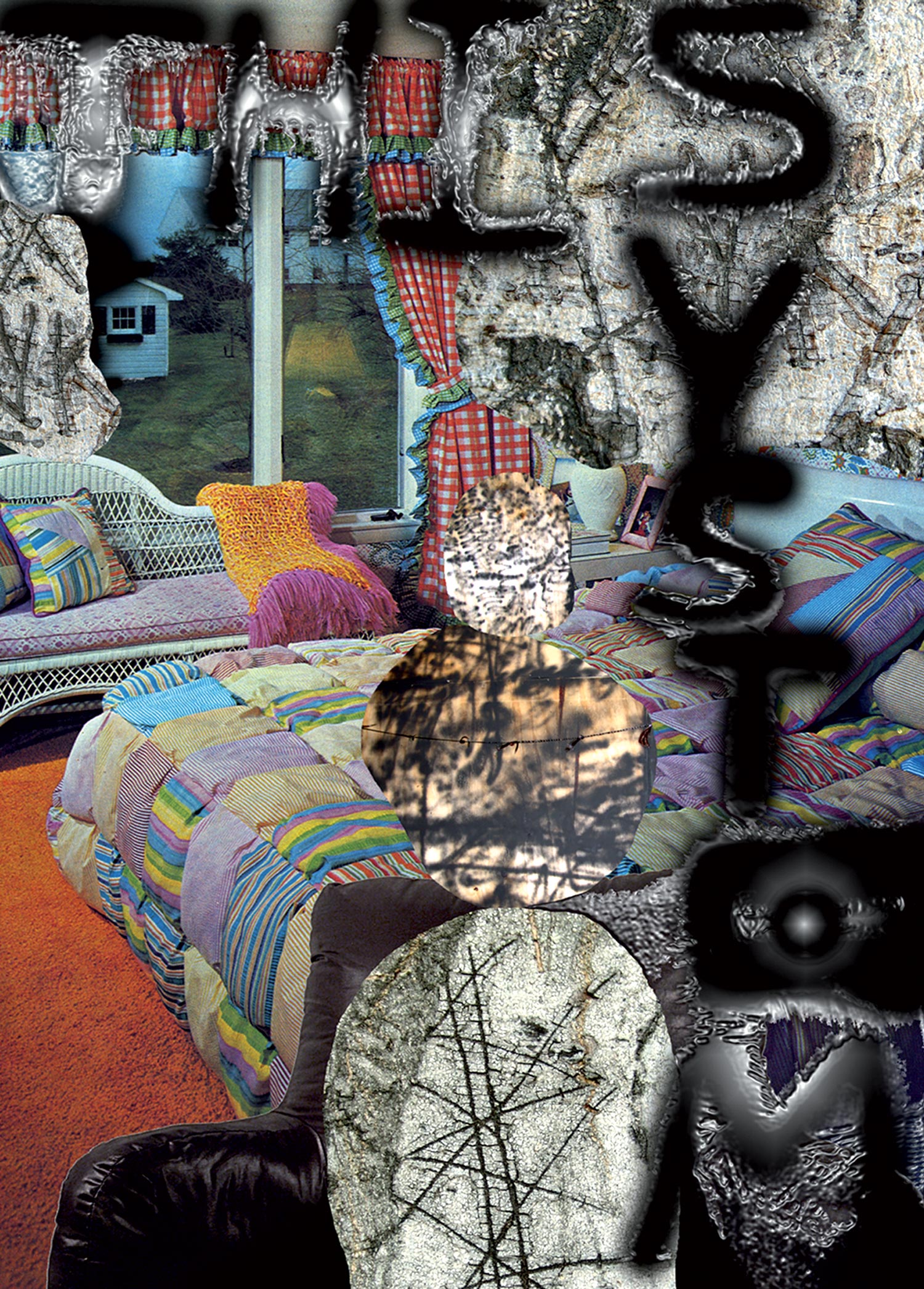

Braun adapted the original screenplay for the stage, cast a group of local amateur actors and set them far from the background of the rural Bengal landscape Ray imagined for his film. Braun’s stage is reduced to striped curtains of cool black-and-white minimalism, echoing the analytical lines of Piet Mondrian, the conceptual ideas behind Daniel Buren’s stripes or the all-over degree-zero minimalism of Niele Toroni’s brushstroke. A small structure consisting of white sculptural elements, appearing to signify the spaceship in the lotus pond, gives the actors something to relate to. The actors wear pastel colored uniform costumes that hint at traditional Indian shirts, strangely blending in perfectly with the concentrated, strictly formalist and pronounced artificiality of the stage.

By representing everything in extreme formalist reduction, as surfaces, or mere screens for projection, the piece gains depth. Not the way that theater operates traditionally, by engaging the viewer through emotional expression (more often than not a bad idea with amateur ensembles), but by mapping a cultural terrain. As the title suggests, the notion of the alien lies at the heart of the project: dealing with the strange, the other, beyond the concept of finding common denominators. Rather Braun pursues a more complex track that aspires to find a new realm by “radically de-territorializing its content,” as the project curator, Grant Watson, put it. No queasy political correctness is at play here, when the viewer experiences himself as much a stranger in this scenario as the alien, or for that matter any other character in the play. What appears as superficiality turns into a refreshing conceptual clarity, facilitating a narrative that unfolds on unexpected levels — change always introduces alien elements to our world. The relationship of tradition and modernity is at the core of this story that locates the space of the political precisely in the realm of everybody’s everyday life.