Jan Tumlir: Hearing about your background and your childhood experiences with your grandfather, who was a well-known local psychoanalyst, and together with whom you drew some of your earliest pictures, makes me look at your work a little bit differently. When one learns that you are actually reproducing some of your grandfather’s pictures in your own, that would seem to make the connection between art and psychiatry overt. On the one hand you have this psychiatrist who is indulging his aesthetic side, and on the other, an artist who is indulging an interest in psychoanalysis; it’s like you’re closing a generational circle.

Mark Grotjahn: I think that maybe for me it’s more about going into my own personal history than finding a relationship between the work and psychoanalysis.

JT: But then there are these hints of something foreign in your work. I’ve always understood what you do as a negotiation between an autonomous modernist aesthetic and something else, like folk art, primitivism, outsider art…

MG: I think it’s true that some elements in the work, perhaps as a starting point, have come from things that would not necessarily be considered art. But these are things that interest me. And whatever form the art takes, it’s always something that’s interesting to me, whether it’s signs or people or the drawings my grandfather did or color or line or oil paint or whatever it is. These are things I’m interested in.

JT: Well, you do take on a variety of subjects and you do work them out in different ways, but what strikes me is that, as opposed to the example of painters like Martin Kippenberger or, better even, Mark Bidlo, who reformulate their stylistic approach for each show or each work, your repertoire is actually quite limited. You keep coming back to the same three or four subjects and styles as if to insist on the relation between them.

MG: I guess they were involved in deconstructing style, which is not really something I’m interested in pursuing.

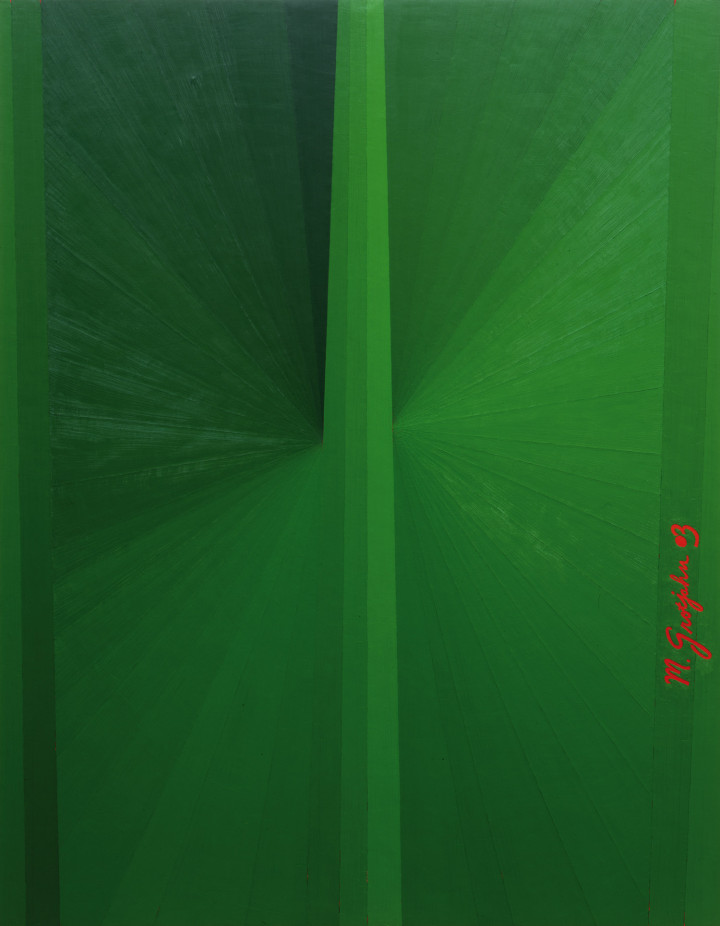

JT: Those painters from the ’80s switched styles so often that they rendered the relation of self to style almost arbitrary — or, at least, that was the intent — whereas in your case, that relation seems much more motivated. When you switch from the relatively streamlined formalism of your “Butterfly Paintings,” for instance, to the “Face Paintings” or the “Masks,” it seems like a deliberate regression. And when one follows your moves in this way, something like a narrative arc begins to take shape…

MG: There are four simultaneous styles going on, that’s true, but what is taking precedence right now is the “Butterfly Paintings.” That’s where my current interest lies. Perhaps some of the other work is not ‘hard-edged’ and is closer to what would traditionally be considered ‘expressive,’ but I’m not sure that it is literally more expressive… I think that way of working fits the thing I am making. The form follows function.

JT: Even if one style takes precedence, then the others still remain relevant as part of your history. Also, although there was a majority of “Butterfly Paintings” in your show at Blum and Poe last year, you still included a very unhinged “Face.” It was maybe to remind the viewer that there is more to your practice than, say, ‘straight’ formalism.

MG: That’s true. And even in the “Butterflies” there’s still always an ‘out.’ If you wanted to dismiss them as ego-driven or something like that, the signatures made that available to you. But I’m not so sure I’m interested in presenting that anymore, at least not like that, not as an ‘out.’ Possibly more as an ‘in.’

JT: You could look at those very rough “Masks,” for instance, as bearing some sort of relation to a pre-aesthetic, maybe even pre-subjective sort of experience. Then you have the “Face Paintings” that begin to suggest the formation of a self-image. And then, that thing that might be called expression is dissolved into the abstract, non-objective view of the “Butterfly Paintings.” That’s one narrative arc you could latch onto if you wanted to, but I don’t think you’re proposing anything quite so straightforward. They’re simultaneous, as you say; these various practices never cease to inform each other.

MG: The “Face Paintings” allow me to express myself in a way that the “Butterflies” don’t. I have an idea as to what sort of face is going to happen when I do a “Face Painting,” but I don’t exactly know what color it will take, or how many eyes it’s going to have, whereas the “Butterflies” are fairly planned out. They’re still intuitive, but I generally know where they’re going. It’s a different kind of freedom, a different kind of expressionism. It’s personal without being overly personal.

JT: Maybe you’re more interested in talking about things at the level of process, but even there, I think, there’s this openly rational side to the “Butterfly Paintings,” the way you divide the canvas into radiating sections and then systematically fill it out, moving from one section to the next almost like the hand of a clock. Then there are the open-ended “Faces”…

MG: But there’s a process for both… They’re different processes.

JT: I’d say that the “Butterfly Paintings” follow a rational line of development that is easily grasped; they communicate their process in a relatively straightforward manner. Whereas the “Faces” suggest an intuitive grappling with the materiality of the paint as well as with the image of self — maybe even a grappling with representation as such. And, for their part, the “Masks” could be seen to emerge from an even more primitive part of oneself. As the different products of the same person, they bespeak the sub-division of the self into these different compartments.

MG: So you’re seeing it as compartmentalizing the self as opposed to integrating?

JT: I would say both. As a viewer I am struck by the disjuncture between these modes of paintings, these very different propositions included in the space of the same show…

MG: …I ran up against that a lot when I did my first shows, where I was working in a whole bunch of different ways, and it was really surprising to me that that this was even a discussion. In a post-Richter world, it seemed to make sense; I couldn’t see why the audience didn’t get it… But in my case it isn’t to show an audience all the things that are now possible; I’m doing it because this thing is interesting, and this other thing is interesting. And I think that it’s worth looking at. It’s worth making art about.

JT: These ‘things’ might be related in various complicated ways.

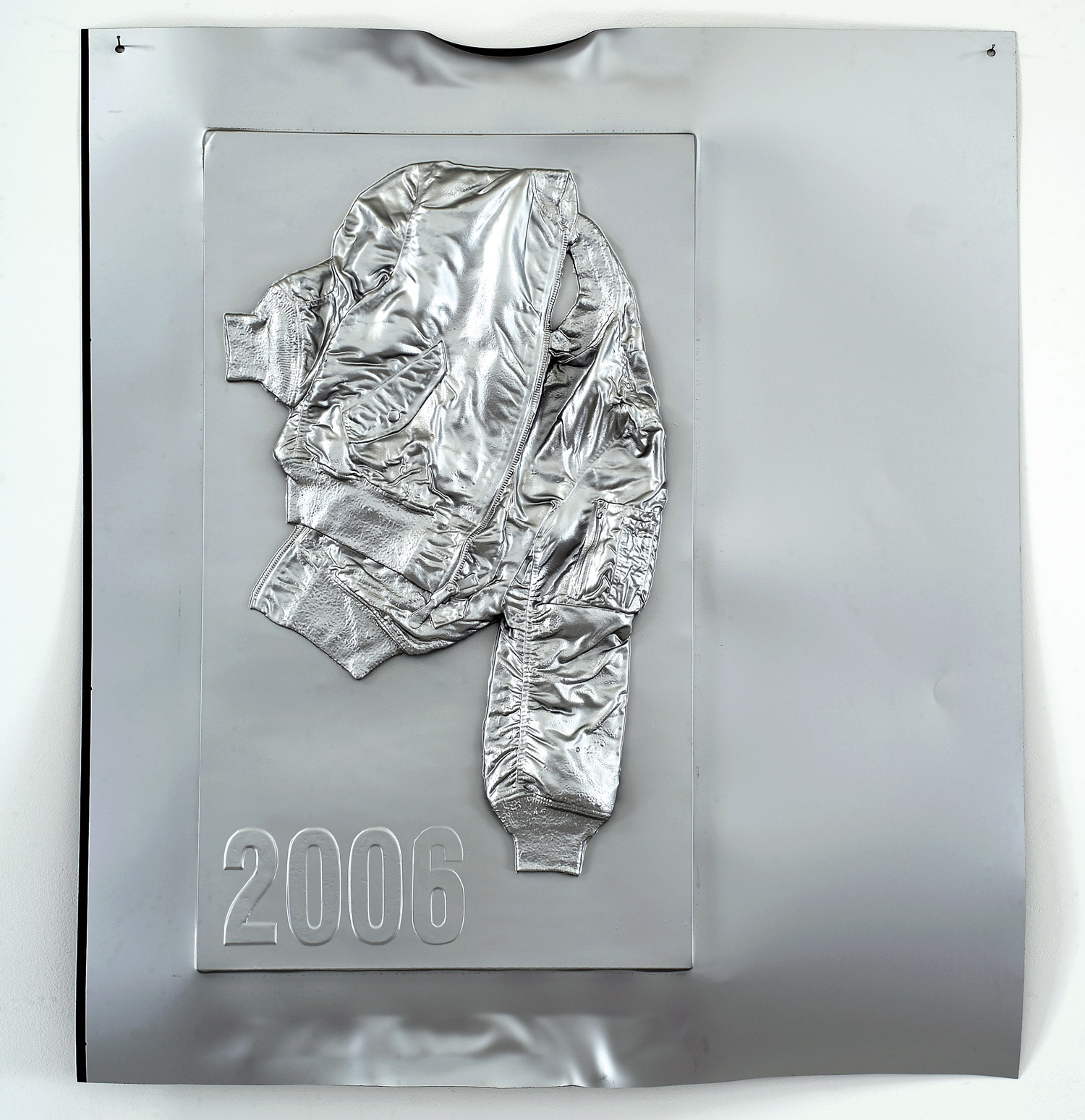

MG: The “Butterflies” started out as three-tiered perspectives, but at the same time I wasn’t particularly interested in perspective. And I’m not particularly interested in masks per se. I don’t see them as “masks” in the metaphorical sense; it’s more just a way to categorize them. Art always seemed like it could be anything, and when I started trading the signs (with the “Sign Paintings”) it went beyond an intellectual process, actually. It became more than just about what the signs themselves meant. It became a way to enter a different place, which would literally be in the back of a liquor store, talking to the owners about making a trade, seeing how they operate.

JT: I’m also interested in the way that the signs you traded, and also the paintings you copied from the sides of these stores, might suggest a kind of immigrant experience. There is that theory that American abstraction came out of a process of uprooting. When artists — Gorky is the case in point — were more integrated within their original cultures, they had specific things to paint, and then they wind up in these big American cities and, to some extent, abstraction is a way of acclimatizing to this new open condition.

MG: I don’t know. The sense that everything’s possible, for me, that’s kind of a given. I don’t feel restricted, or I don’t want to feel restricted, by any rules.

JT: Yes, but then what do you do with the freedom?

MG: Well, I do the things that I want to do. I paint abstract paintings because I like abstract paintings. I paint faces because I paint faces. I made abstract paintings and drawings when I was a kid; they were a kind of design. In high school I had a teacher that showed me Kandinsky, and then I read The Spiritual in Art, and that helped bring me to a point where I thought the designs I did were art.

JT: You’re saying that you always bring it back to some private, early experience?

MG: Not always. When you look at the “Flowers” and the “Faces,” would you know that they were personal? Would you know that they were based on pictures originally drawn by my grandfather who was a psychiatrist? I don’t think that this information is readily available. I guess it is out there. It comes out in interviews like this, or if you talk to the gallerist, you can get it that way. But, in terms of the actual exhibition, I’m not sure how much this information really matters.

JT: But it is, at least, implied… You brought up perspectivalism, which is traditionally understood as a systematic means of situating the subject with respect to the object of vision. When you forcibly warp that system, like you do in your most recent suite of drawings which is up right now at the Whitney Museum in New York, that has direct psychological repercussions. So, again, I wonder: If everything is possible, but if you don’t want to do everything, like Richter does, then what do you do? It sounds like you’re saying that what you do is what you’ve always done, which takes us back to your earliest experiences and your earliest happiness in art-making.

MG: I’m talking about what I do. All I can say is that this is what I’ve chosen to do with my art.

JT: But if you answer that question solipsistically, then all those biographical details do start to matter to a viewer. And this is just as true at the level of process: The fact that you actually copied your grandfather’s drawing, that you used an opaque projector, this suggests to me that it was important to get it right, let’s say, in an historical sense. Your insistence on the particular quality of his line, on keeping it from becoming completely absorbed into your own production, and even the way you’ve tended the archive of your grandfather’s drawings, each one carefully sealed away in its protective envelope, leads me to believe that it does matter. You’re clearly attaching some sort of importance to these things-in-themselves.

MG: My grandfather’s drawings are very important to me; they have a lot of personal significance. I also find them very beautiful. The flowers, which comprise the main body of his work that I’ve chosen to appropriate, are probably the most beautiful and at the same time, they are the least autobiographical when you consider that the majority of his drawings were actually cartoons of himself and his family and his life. So I guess part of the reason I chose to copy his flowers over, say, the drawings he made of his family, is to keep the personal a little bit at bay… At the time, I was copying the signs; I’d make a sign, then I’d trade for it, and then I’d bring the other sign in too. So I was doing this appropriation work, and then I wanted to make the appropriation a little bit more personal, like appropriation for personal expression.

JT: Right…

MG: And so I started doing the funny “Faces” in the spirit of my grandfather, in the same way that when I trace his drawings, I know the sounds he made with every movement. I know what it sounds like, and I know what it looks like, when he drew them… The “Faces” came out in the spirit of him, although I don’t know that he would actually like the work, and maybe he would feel I was ripping him off, but, for what it’s worth, it’s still in the spirit of him. And, recently, among the last few “Flower Faces,” I did a portrait of myself and then a portrait of my wife… Maybe I captured something; if not the likeness, then maybe something else…

JT: It sounds like you want to personalize a type of practice that is, historically at least, opposed to the personal. That is definitely one answer to the question of what do you do when everything is allowed. You can actually start dealing with your own personal history in a more intimate or meaningful way. But then you’re also talking about wanting to keep a part of the personal ‘at bay.’

MG: That’s true. It’s funny because the two parts of me and my wife come together when I do the “Butterflies,” now that I’ve actually taken out the name. And before that, before taking out my signature, I put in “Big Nose Baby and The Moose,” which is something that a friend of mine used to call me when I came out of the pool. He thought I looked like a baby moose.

JT: These sorts of personal anecdotes are important in generating some aspects of the work, but then you seem to be ambivalent about the relationship between these and the finished product.

MG: I don’t know if it’s that I’m ambivalent. I believe there are relationships; it’s just that I’m not sure how concerned I am with being able to verbally exact them. There was a time when I really believed that if you were going to put out work in the public, as a responsible artist you should really know exactly what it is that you’re doing and be able to speak about it. Well, I definitely don’t think that you have to. Let’s just leave it at that.