Other echoes

Inhabit the garden. Shall we follow?

— T. S. Eliot, “Burnt Norton” (1936)

A beat bounces off a canyon, a surface, and back to an eager ear in a distorted return that we call echo. Once this happens, the original sound is never quite the same again but something nearby, a coy, distant version of itself. It stretches and distorts like a memory recalled decades later. Like an echo, Marina Xenofontos’s practice retreats away from us: around corners, down corridors, across time and geographies. It shifts between surfaces, reverberating off objects and images before returning a shock of comprehension. Agitating representations that surround and structure lives, the artist loosens something in our sedimented attachments to site, identity, history, and ideology. Her drive to contest fixity in this way sits uneasily with language and its predilection for clarity and determination. This text then should also be considered as an echo bouncing off the work, becoming more and more distant, amplifying moments or memories of a practice that continues to distort, reshape, and destabilize itself.

Frequently romancing failure, Xenofontos often works with methods or materials that are unfamiliar to her, recreating the conditions for the journey from misunderstanding to understanding to begin again. The (re)development process of some works spans years or, for some, more than a decade. Twice upon a while (2018–ongoing), a video game, so far in development for six years, follows Twice, an “ideologically befuddled teenager failing to complete her tasks.” Twice, an avatar whose name reflects Xenofontos’s interest in the double, arrives in both digital and analogue form across several of the artist’s creations. Like a designer dupe, the avatar collects new imperfections or inconsistencies with every reproduction. Xenofontos’s projects themselves are similarly iterative and changeable; they become witnesses to resounding memory, enfolded like markers into personal and social history as it takes place.

The teenager, someone who is still figuring out what things signify and how to relate to them, is a symbol that resonates elsewhere too. Things We Lost (WIP 2024), a new film being shot in Cyprus at the time of this writing, will follow a group of teenage girls as they travel from Limassol to resort-town Ayia Napa for a night out. The journey is a rite of passage for many young islanders, including Xenofontos, whose storyboard for the film includes photos of her and her friends as teenagers on nights out in Ayia Napa or getting ready together in acid-green and blueberry-purple bedrooms. The town exists in many European minds as an image of overflowing clubs, flickering neon, and screeching partygoers. It is also located beside one of the United Kingdom’s largest military bases, an English identity further reinforced by the continual influx of rowdy British tourists. In the film, the aftermath of a night out will mirror the topology of the town: its strips of clubs and hotel blocks, as well as the histories and sites hidden behind its glowing image.

The reverberation between time, site, and experience is a repeated convergence in Xenofontos’s practice. In her solo show “Public Domain,” at Camden Art Centre, London, in 2023, Xenofontos brought three works into material conversation in one room. At the center was King, oh King, with your 12 swords! What work do you have for us today? Laziness, the King demands, and the children all reply, Let’s get to work! (2023), silver-plated bronze casts of wooden walking sticks, like those used by Xenofontos’s grandfather, stacked to the ceiling, forming two slender stalactites slowly and slightly clumsily rotating. Such oscillatory movement is a motif in Xenofontos’s artwork. Just as a struck tuning fork transforms the surrounding air into a frenzy of sound waves, Xenofontos unsettles our understanding of objects. One’s grasp of each work bounces away and back, back and away, becoming a ringing in the ears as materials and self-histories collide and resound.

On the other side of the room, two white cables cascaded from above, their presence betraying the motor that enabled an inelegant dance of poles. Tumbling from the ceiling to the floor in two lines, they mirrored the form of King, oh King!, their slack, dangling state functioning like a release valve, whereby the tension between objects might evaporate. The same work retreats across time with various iterations spanning nearly ten years; it made its first appearance in 2015, at Neoterismoi Toumazou, an influential-but-now-defunct artist-led space in Limassol run by Xenofontos, Orestis Lazouras, and Maria Toumazou. There, a disco ball motor was repurposed by the artist to rotate a simple metal pole that connected floor to ceiling as part of her first solo show, “Karat Castle.” Later, with the addition of a bronze cast of one of her grandfather’s walking sticks, the same work was installed at the Rijksakademie Open Studios (2019) and Hot Wheels Athens (2020). Each iteration has been a reference to the past and a half-glimpsed premonition of what’s to come. Just out of reach.

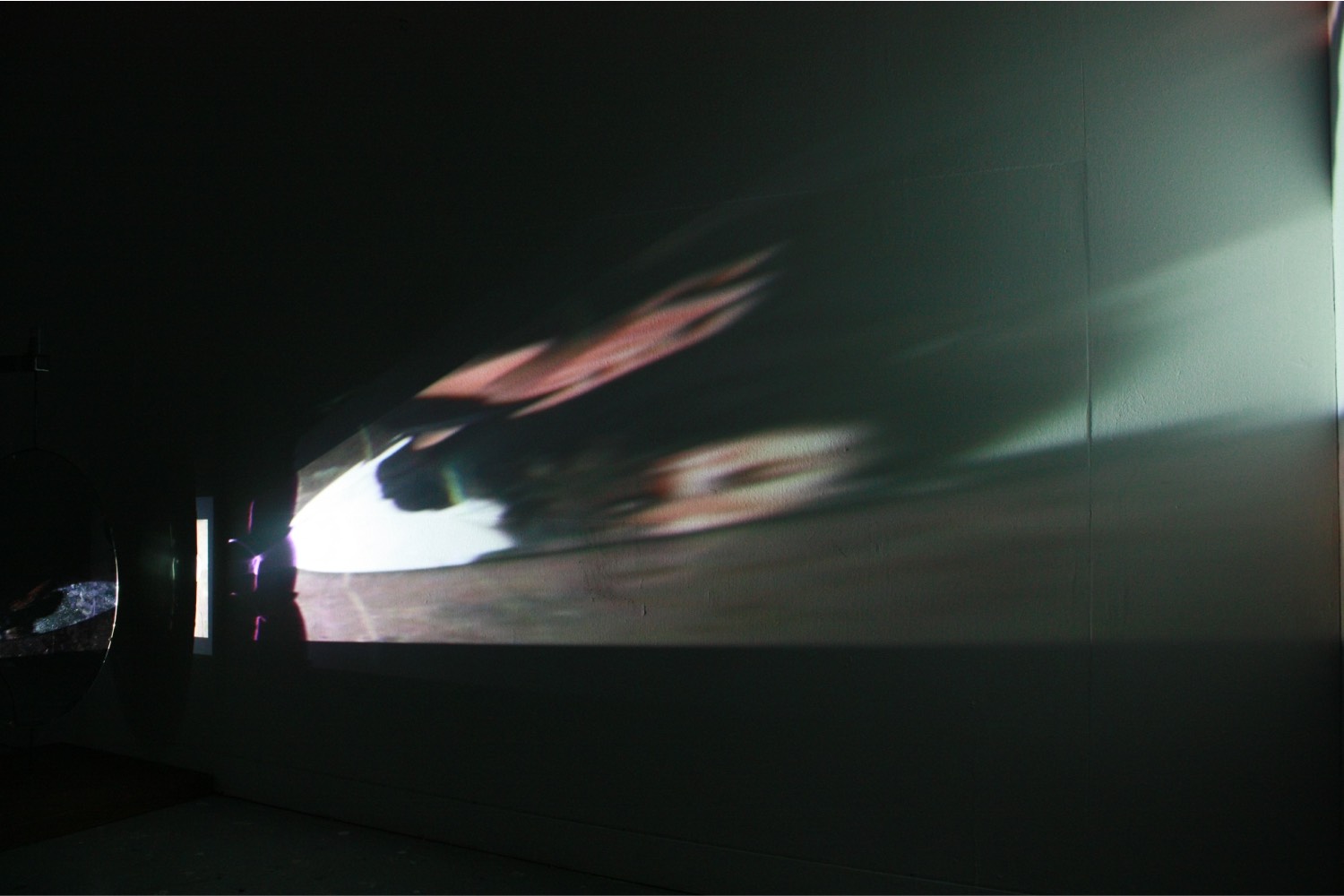

This returning and reworking was seen again in Xenofontos’s “View From Somewhere Near” at Kunstverein in Hamburg. The exhibition comprised Code of Construction (2024) and Sequencer (2009–24). The latter is an artwork that she has continually revisited in the studio, making several versions over fifteen years. A moving image is projected onto a spinning oval mirror; an ant — often a cohabitant in our homes, especially during the summer months — is shown in its final moments of life. Magnified on film, an event that might otherwise go completely unnoticed is recast as a Shakespearean tragedy. Sequencer was Xenofontos’s earliest foray into kinetic sculpture, and the first time she incorporated light, mirrors, and reflection. These materials have since become foundational to her practice, and so, in Hamburg, the work functioned as a kind of codec. Code of Construction had an austere presence: a series of dark brown wooden cabinets sat along the walls in a curt L-shape, dense and immovable. Their specific design was a model for bedroom cabinets across Cyprus until the early 1980s. They’re the kind of multifunctional objects that form an inoffensive backdrop to life but become laden with meaning over time as lives play out and your distance from them grows. They take their style from furniture typical of the British colonial period in Cyprus — the British Occupation was 1925 to 1960, but its impact on the island stretches out on either side. In Hamburg, in an almost unlit gallery, Sequencer bounced, skipped, and distorted across the cabinets and onto the gallery walls, like a lighthouse beacon emitting frantically into the darkness. Together, both works point toward the way in which dichotomies of inconsequential and profound, innocent and not-so-innocent, can sit comfortably side by side in lives: a dark and irreconcilable complexity experienced as mundanity.

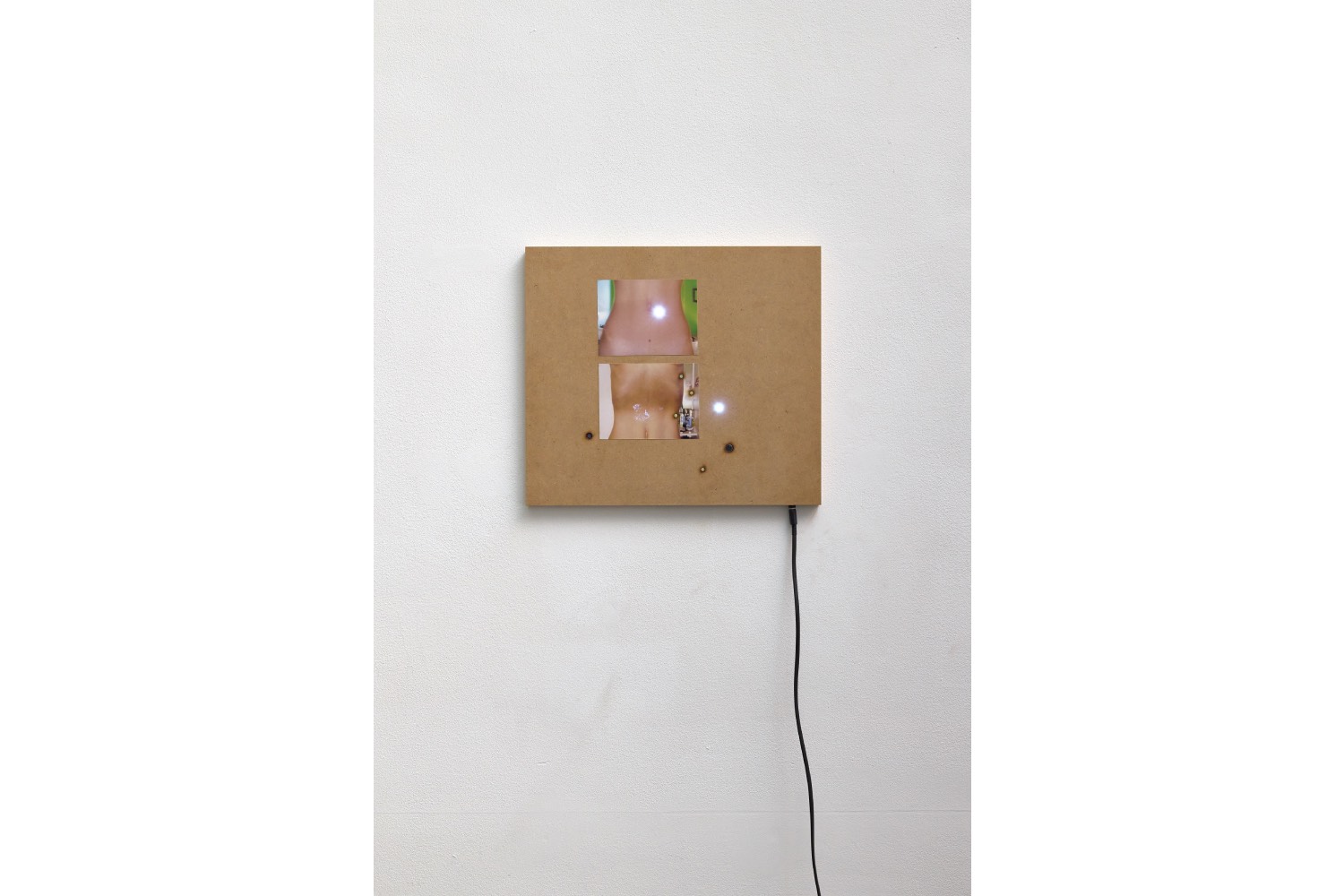

These echoes travel across geographies too with a presentation at SculptureCenter taking place in New York simultaneous to the Camden Art Centre presentation in 2023. Monobloc chairs appeared in both shows, like cheap, plastic ellipses. In New York, they formed part of a new film installation, NEW FAITHFUL (2023). The displacement between sites echoed the subjects of the film — archival footage of dancing Cypriot refugees in the UK and US in the 1970s and 80s. The exhibition also contained site-specific works Control Board #1 and Control Board #2 (both 2023): copper cylinders that awkwardly adorned the walls of the gallery, placed just below knee height. Each was powered by a synchronized motor connected to sound and motion sensors, fixed on a lo-fi control board made of MDF. The cylinders turned at increasing or decreasing speeds depending on inputs, and emitted a grinding, droll, industrial drone. Cyprus has been known for its abundance of chestnut copper deposits since antiquity; the etymology of copper is derived from the Greek name for the island, Kupros. During British occupation, the aggressive mining of this copper and the failure to regulate it led to a mass exploitation of workers and a rapid extraction of the mineral from the ground. Deposits in Cyprus were quickly exhausted, leaving the landscape ablaze with shrieks of burnt red and contributing to the economic decline of the island. Today, copper is being used in the production of AI technologies, with demand predicted to double over the next ten years. Displayed in the gallery, untreated and doubly exposed, its futile movements triggered by others, the work feels like a raw, exhausted nerve.

In his beautiful poem “Burnt Norton,” T. S. Eliot ruminates on the idea that the past can’t change, the future can’t be reached, and that the present is the only part of time where we can intervene. He encourages the reader to remain in the present and not to follow the “echoes in the garden.” Xenofontos, instead, makes us chase the tail of echoes as they bolt out of the garden, arriving somewhere we’ve been before but don’t quite recognize. In the spaces and time between works, she reveals that the past, present, and future are active and contested sites, making visible the ways they bounce and reflect off one another — in our collective memories, social lives, architectures, and the objects we hold dear.