The title of Marina Pinsky’s fourth exhibition at C L E A R I N G Brussels is taken from a mid-nineteenth-century theory, according to which it is possible to highlight the regions represented on any geographical map using only four colors. The political complexity of the contemporary world could therefore be visually represented using only yellow, green, blue, and red. This concept could only appeal to Marine Pinsky, who has always paid particular attention to the places in which she works or exhibits. The exhibition is thus placed under the sign of cartography, as shown by the large installation that occupies the center of the gallery: seven aluminum disks suspended from the ceiling, showing on one side heptagonal photographs produced by Theodor Scheimpflug’s aerial camera, invented in 1897. On the other side are displayed reproductions of various ancient celestial maps, such as the Nebra SkyDisk (1,600 BC) or Korean astronomical charts from the Joseon Dynasty (eighteenth century). With the evocation of these ancestors of Google Earth and Celestia, Marina Pinsky refers to some of the major preoccupations of humanity since the dawn of time: the observation of the earth and the knowledge of the cosmos. Playing on a contrast between microcosm and macrocosm, she transposes these universal questions to her daily life with a series of bronze scale models referring to the places she inhabits (Koekelberg in Brussels, and Hansaviertel in Berlin). The images taken from Google Maps, by nature ephemeral (they are regularly replaced by more recent ones), are thus frozen in a material designed to defy time.

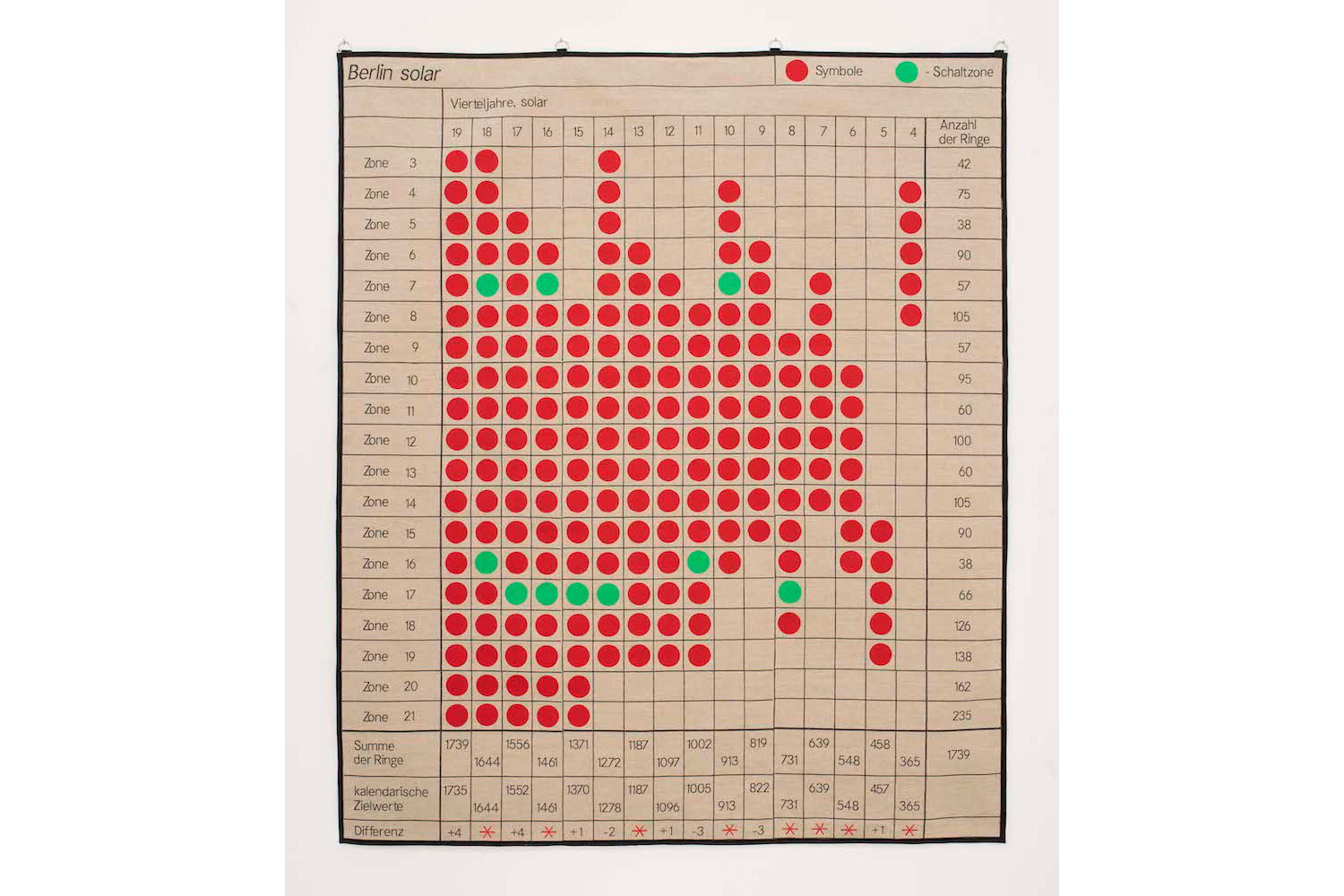

Time is precisely the second part of this exhibition, featuring a series of wooden reproductions of the Golden Hat (1,000–800 BC) kept at the Neues Museum in Berlin, a ritual object presumably used for the determination of dates in both lunar and solar calendars. Pinsky visually transcribes its symbols using the three additive primary colors, added to the tint of the raw wood. These Golden Hat Mandrels have the appearance of manufactured objects, but the artist also resorted to artisanal techniques to create them: egg tempera paint, marble dust, and rabbit-skin glue on turned limewood. Pinsky’s proposal to unify time and space, the universal and the personal, is certainly coherent but perhaps overly ambitious. And, as Marcel Broodthaers demonstrated in 1975 with The Conquest of Space: Atlas for the Use of Artists and the Military, recourse to the monumental is not a sine qua non for evoking the human relationship with the immensity of the universe.