Helena Kontova: You’ve been Conceptual artists, then you were Body artists, and now working together you talk about “Art Vital.” Can you explain what this term means and why you started using it?

Marina Abramovic: Our work deals with our bodies and that makes us think about vitality. To explain Art Vital we think of the idea of permanent movement; direct contact; passing limits; taking risks!

Direct contact with people, for example, gives us a new feeling about our bodies and moulds our daily lives. And it gives us a completely new way of working too.

Ulay: We didn’t agree too much with the term Body Art and we started to talk about vitality, because after every performance we felt regenerated

HK: Do you consider your life as a work of art?

U: No, not in our case. We would just like to fill the vacuum between our everyday life and our art. This gap is especially evident as it concerns European artists. At the same time, there is nothing bohemian about our daily behavior. The fact that we live in a van, that we don’t have a house, and that we travel continuously, is simply a necessity for us. In order to make our work we must reduce our needs to a minimum

MA: For us, our daily activity is exercise, which keeps our bodies in good physical shape.

HK: I see a lot in common in your present and past work, when each of you worked alone. Especially the idea of taking risks, going to extremes.

U: It was something very different.

MA: My earlier works for instance were based on pain, they were very drastic. If I hadn’t met Ulay, they would have destroyed my body. I was very fatalistic and more and more destructive, and by the time I met him I’d made the liberation pieces out of that feeling of destruction. I called those pieces Liberation of Voice, of Body and Memory. And then after we started working together our art became constructive.

U: The work we do together could not come from one person, but the interpretation of our work is mostly wrong. For instance, Marina doesn’t make feminist art. I think she agrees…

MA: I do…

U: I think people are always thinking of us as a symbol of a man and a woman, and of course in a biological way we are. But we do not want to represent an Olympic game between men and women. Our performances don’t have the mentality of the Olympic Games or of Cassius Clay. Of course there is a difference between Marina and me, but equally there is a difference between one man and another. So we negate the general idea of man and woman. I think the two of us are more liberated than feminist or non-feminist artists, or any single artist. Because a single artist, a single person, can’t get the results we do. We have two impulses of two people, and there is one result.

MA: Another thing about Ulay’s and my earlier works is that they show the traces of frustration.

U: A Sexual frustration…!

MA: You can clearly see we were unhappy and alone. If your sex isn’t good, everything’s wrong, and then you do things, for instance, like Gina Pane. And when you repeat things like her, the work’s sick. The message of art should be wider than that.

HK: You told me you’re completely liberated from the feeling of man and woman as two antagonistic beings fighting each other. But at the same time you can’t refuse that the fact you’re a man and a woman gives your work special meaning. What’s your opinion on ‘man-woman?’

MA: I feel the perfect human being is a hermaphrodite because it’s half man, half woman, yet it’s a complete universe.

The man is only half and the woman is only half. Together they’re perfect. Intercourse is the only act where man and woman are near the universe because they’re one complete person. We’re a man-and-woman. I am half, he is half, and together we are one. And one can do more than half!

U: We might do three things. First Marina might work from the feminine side, second I might from the masculine side, and third we might work together. And the third possibility is our case.

MA: We don’t feel one uses the other. We’re both completely free during performances. I can stop and he can stop when we want. The end of each performance is always open, neither of us knows how it’ll end. We don’t plan it.

U: Going on about the relation of men and women, it’s perhaps difficult to understand our case. Because there are many examples in art of men and women working together, but they’re usually two separate beings, and they only appear to be together. But Marina and I live together 24 hours a day, and we also work together. It must be said that Valie Export and Peter Weibel represent a totally different situation: they worked together, had a relationship, but never did ‘Relation work’ like us… For me it’s very difficult to live in a woman’s time. The only way I’ve found to live like this was a few years ago in ’73, when I was a transvestite!

HK: To return to your earlier work, do you feel there was real physical risk?

U: I made perhaps some psychologically difficult things, but I wouldn’t call it ‘risk.’ I would call them ‘treatments,’ to liberate myself from traumas. I didn’t want to exist with such traumas. My art was a kind of freeing.

MA: Yes, Ulay’s works were more depressive in a psychological way but mine were more physical. They were based on some kind of danger and risk. I often went to the limits, but always in front of an audience. I was showing danger — my limits — but I didn’t give any answers. The result was not a real danger but only the structure I created. And this structure gave the observer some kind of shock. He wasn’t sure anymore: he was unbalanced and this made a void in him.

U: Risk in our earlier work was aimed to shock the public. This shock Marina mainly used with audiences directly, whereas I only used video for six years. But together we’ve slowly stopped trying to shock. Formally, however, we’re still near this, as we’re still examining our physical possibilities. I think I should point out after every performance we feel physically better than before. After the performance in Kassel for example we drove away immediately, because people always have pathetic questions, like, “Didn’t you hurt yourself?” “Didn’t you feel pain?” And so on. But you know, the pain didn’t exist. The dramatic experience, the dramatic fear, the public just projects onto us.

HK: So you don’t mind physical pain or other unpleasant physical feelings. It’s not important at all for you?

MA: More important is why we do it. It’s like an operation, when they cut you with a knife, but at the same time the operation’s positive. The knife is necessary for your health. Early in my work the pain was almost the message itself. I was cutting myself, whipping myself, and my body couldn’t take it anymore. I was really at the end, if I hadn’t stopped I wouldn’t be here any more. Now with Ulay my work is more constructive in an optimistic way.

U: Our work is real-life drama. Everybody needs energy just to do his daily job. In our art we want to reach what I call ‘autonomic’ energy. The energetic reserve everybody has. Like a chicken, if you cut off its head, it can still fly away; this is autonomic energy.

HK: Is there some kind of philosophy behind your art?

MA: We have no knowledge of philosophy but we try to reveal our own experience. We have no idea that we follow, we try to do a work first and then think it over after. It’s very important for us not to have a fixed philosophy and work in a box. We decided to have the biggest experiences we could in everything. So as we speak about a reserve of energy, about our bodies, you might think Zen Buddhism’s behind our work, or other philosophies, but we’re really interested only in experience!

U: We’re interested in philosophy but we don’t identify ourselves in any particular one. It’s only one year that we’ve been working together; so far we based our art on an individual experience.

HK: Do you think activities where you deliberately expose yourself to difficult situations can change our cultural feelings and observations?

MA: One thing is to use our body consciously, to expose it to danger knowingly. Another way might be to go fast, say in a car at 800 km/h and to kill oneself. But that’s very different. Using your body consciously and still taking risks, going to the limit while still in control, that’s new. But I’ve never felt my works were dangerous, danger was an illusion people felt.

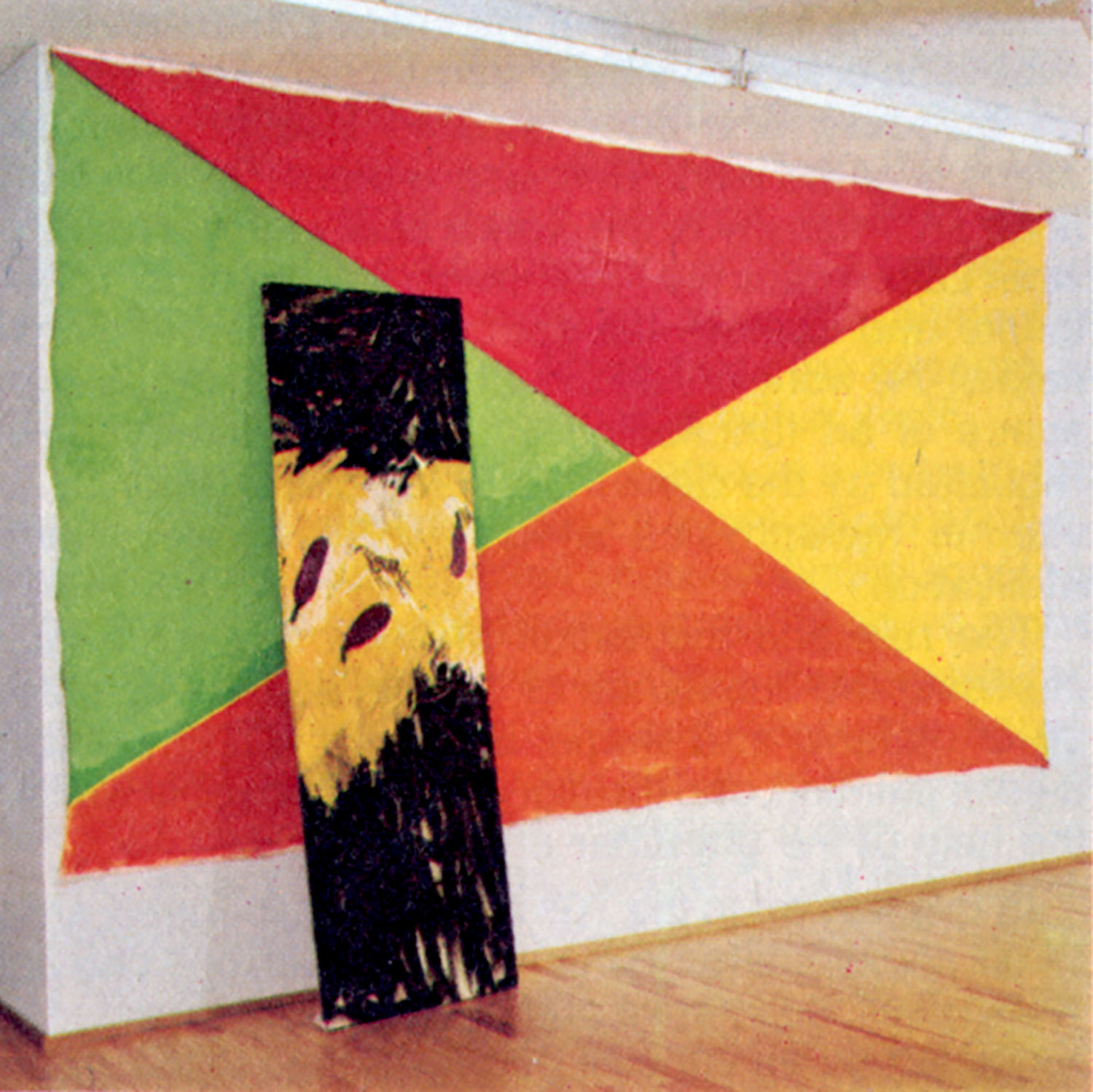

U: For us it’s important seeing people’s reactions. For instance in Kassel where we were doing Expansion in Space (1977) people reacted terribly.

HK: Do you always use one video camera on the audience to see their reactions?

U: Yes, we always record it.

MA: In Kassel 90% of the people were reacting only to two beautiful bodies hitting the wall. Much more important for us was the idea of expansion; demonstrating our energy as it expanded in space was all that was important.

U: People watching performances are always more irritated by physical things, mostly impressed by the actual process; very few really understand what we’re doing.

MA: Once in Yugoslavia I went to a hospital and asked a doctor, “What’s the most dangerous operation?” He told me that it was the operation on the brain. And I watched for six hours the cutting and sewing with needles and thread. And what I thought at the time was what we do in art: it’s not really dangerous — it’s only illusion! Artists like Ulay and I are very far from real feelings and intuitions. People living in the countryside however are much nearer to the body, to danger, to existence. Living in the cities, we indeed are protected by everything, which makes a confrontation with nature almost impossible.

HK: I read an article, “Art and Sacrifice” by Jan Chalupecky, dealing also with artists like you or Chris Burden, where the author interpreted this as a certain type of sacrifice. Do you agree?

U: No. I find it very Catholic. I am against the manipulation of Catholicism and it’s moral!

MA: I think it’s not serious causing pain to your body, because the body regenerates quicker than you think. When I come to the limits of my resistance, I feel terribly alive…