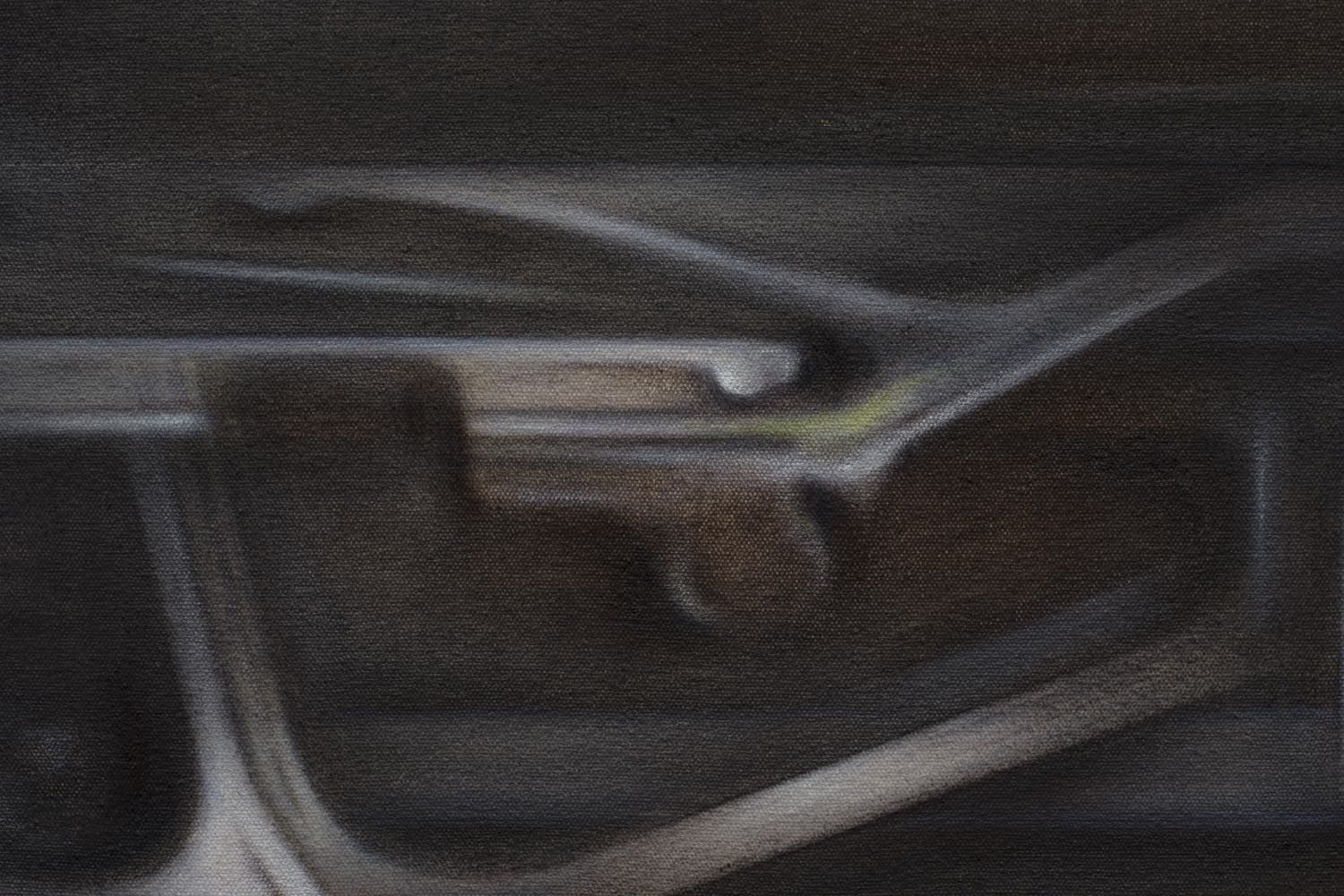

It’s easy to forget that painting itself is a technology, but before the arrival of photography, painting possessed the unique capacity to conjure that which is beyond physical reach. In Maren Karlson’s paintings, the sleek components of mechanical parts convincingly suggest the sophisticated inner workings of a world that lies just beyond our own. Bodily and machinic structures seamlessly twine: soft folds rendered in muted, monochromatic palettes siphon off into shadowy channels and sinewy networks that run the length of narrow canvases, scaffolded by glinting frameworks. Whether filled with pliable tissues or vaporous, whirring components elongated in defiance of physical law, her paintings often retain the composure of an ultramodern product whose skin is as permeable as ours. Scale is elusive, and time is too: we might be looking at architectural renderings, topographical landscapes, or devices implanted into bodily cavities. They might exist in both the distant past and future. Familiar but unnamable, Karlson’s biomorphic abstractions subvert our understanding of systemic structures and pull back the curtain on constructs of bodily purity and natural order.

Karlson’s distinctive visual language echoes both the fantasies and anxieties of frictionless capitalist production touted by the particularly spectral brand of American dream on offer in Los Angeles, where the artist lives and works. Its promises of smooth, ageless bodies and subtle technologies that obscure visible labor and mortality might reflect what post-capitalist philosopher Mark Fisher called the Gothic Flatline, a conceptual terrain “where it is no longer possible to differentiate the animate from the inanimate and where to have agency is not necessarily to be alive.”1 In Fisher’s suspended realm of smoothly operating automatism, barely perceptible capitalist structures keep us passively inert. Karlson’s paintings allow us to consider the conditions of permeability, decay, and dust that might unsettle this illusion of natural order. In her recent exhibition “Staub (Störung)” (Dust [disturbance], 2024) at Soft Opening in London, dust looms like an agent of chaos over vertiginous paintings of fleshy surfaces fitted with machine parts, propped against the walls or inset into the recesses of a gallery column. In Staub (Störung) 7 (2024), a constellation of gears and fittings nestle neatly into bodily cavities. Rendered in a jaundiced palette, soft and modeled comes up against rigid metallics before disappearing into a crack or shadowy fissure, as in Staub (Störung) 1 (2024). By probing these seams, Karlson provides glimpses into the disorderly potential of errant forces that underlie fragile, skin-deep veneers and all closed systems of control. Dust — that pervasive substance we endeavor to expunge from our aesthetic lives — might be the byproduct of their industrial production as much as a destructive force that could undo it.

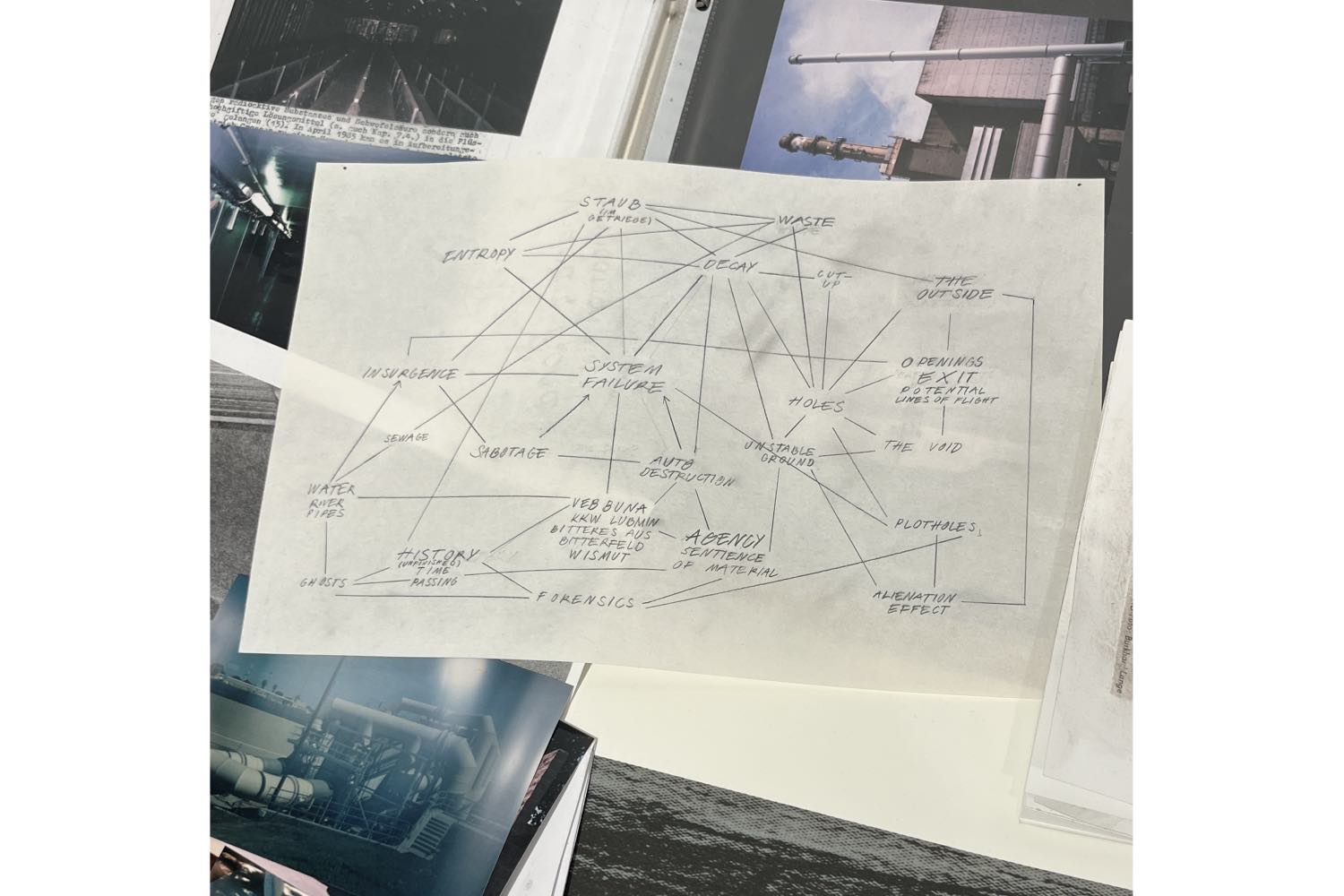

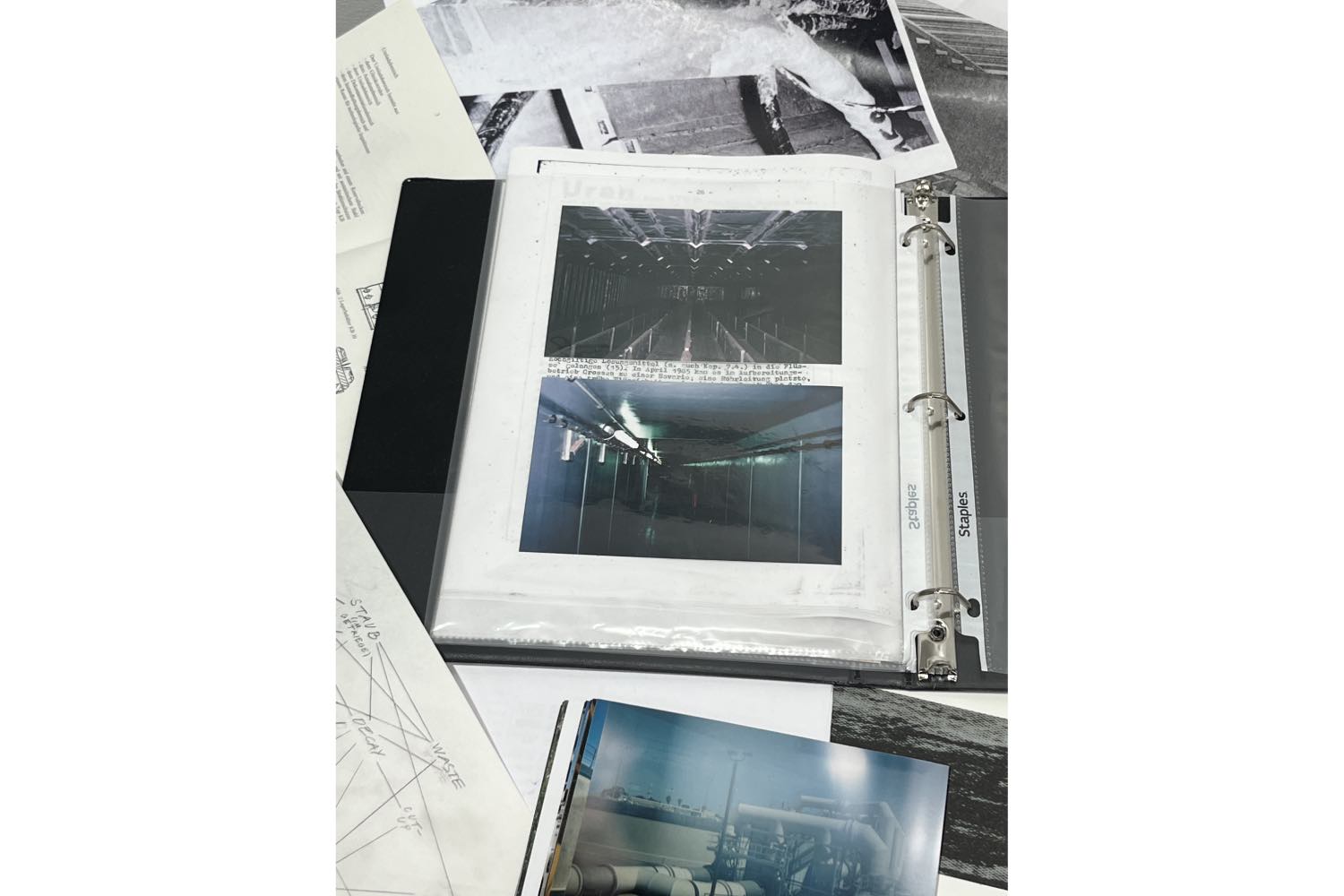

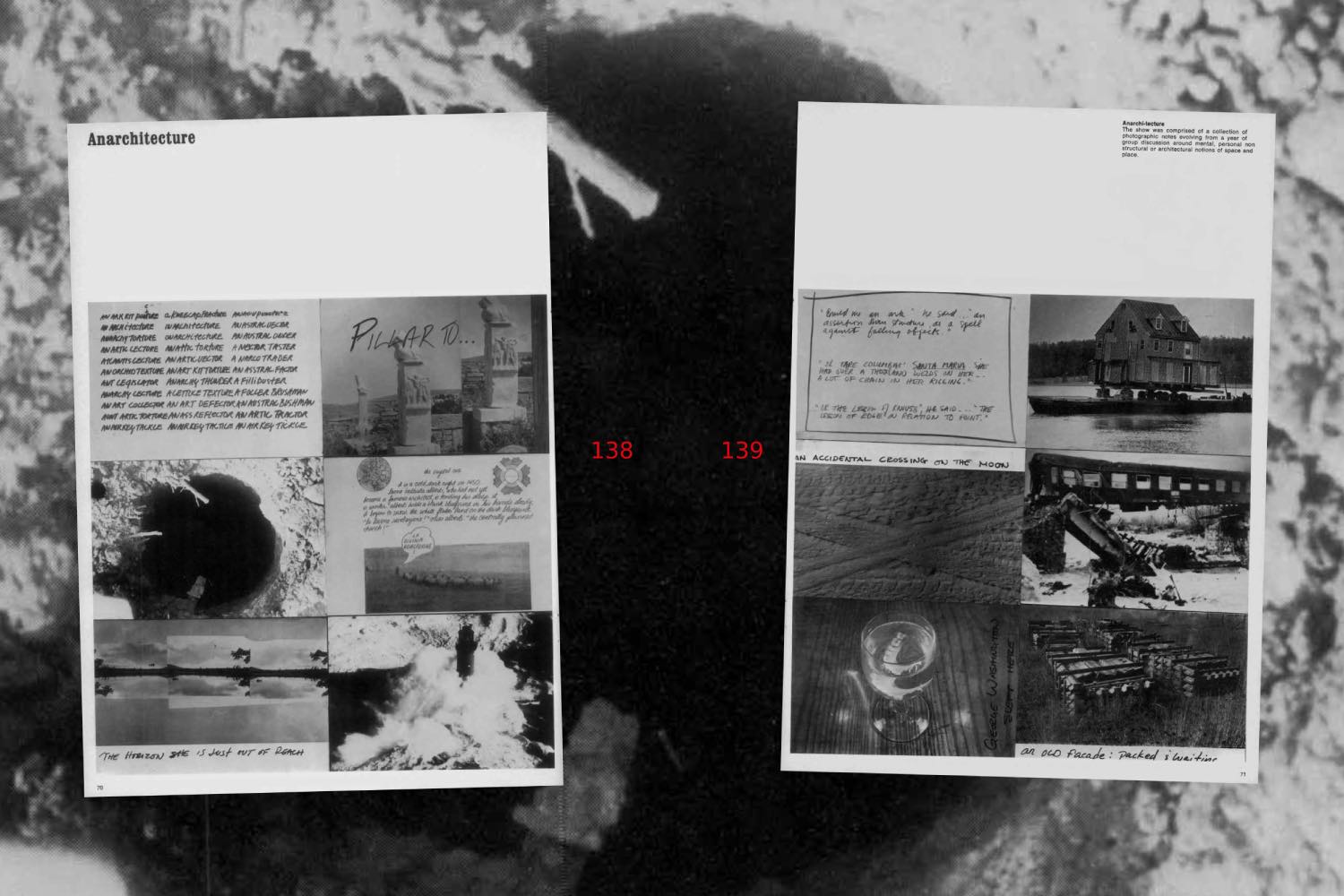

Contrary to twentieth-century ideas that abstract painting arises spontaneously from the interior world of the artist, Karlson derives her abstractions from an archive of found objects and photographic documents that reveal faltering systems on both micro and macro scales: X-rays and endoscopic footage of her own bodily organs during illness, declassified government documentation of dangerously unstable factory conditions, industrial and technological detritus, or photos of escape tunnels dug through prison walls and bank vaults. “I’m interested in these holes that open up in moments of system failure, for better or for worse,” she explains. The dissolving mechanisms that appear across “Staub (Störung)” can be traced back to photographic evidence detailing structural failures at the Kombinat VEB Chemische Werke Buna, the main factory in Karlson’s hometown of Halle, while it was under Soviet occupation. The photographs were classified by the Stasi until Germany’s reunification in 1990, two years after she was born. Honing in on specific elements like valves, connectors, and wiring, Karlson reworks their visible decay and background noise into form, drawing ghostly apparitions and connective tissue from the debris and photochemical artifacts.

The exhibition’s title comes from another declassified photograph of the word “STAUB!” traced into a layer of blackened particulate across a bank of snow in front of a house in East Germany, captured near a uranium mine. The image shows radioactive pollution encroaching on residential life, a scene that recalls the vehicle and industrial emissions that hang in the air over present-day Los Angeles. For Karlson, the impending threat of environmental catastrophe and anxieties of bodily preservation haunting LA’s pristine surfaces bear uncanny parallels to the overtly threatening environmental conditions of her upbringing in the Central German Chemical Triangle, a post-Soviet region dominated by chemical plants and coal mining. Pollution in the LA river, concrete channels built to funnel groundwater and freeway traffic, pervasive smog, and a relentless pursuit of health and wellness, correspond imperfectly to the Saale River in her hometown of Halle, its brutalist architecture, factory pollution, and public health issues. Attuned to these strange transcontinental echoes, Karlson distills photographic elements into abstractions that mimic reality while presenting it wholly defamiliarized, as she found the conditions of her material past reflected to her in Los Angeles. While the use of distortion as a strategy for defamiliarization remains consistent throughout Karlson’s practice, her recent work evidences a shift towards an unsettling anatomic and scientific verism in which the subjects have all but completely dispersed.

For Karlson, holes are a generative force for new pathways, and a recurrent motif across her recent paintings and drawings as voids, passages, egresses and ingresses. Holes are also a bodily reality that trouble ideations of security and render us vulnerable to our surroundings. For her latest exhibition “Staub (Holes)” at Hannah Hoffman in Los Angeles, the artist collected documentation from undisclosed nuclear accidents between the Santa Susana field lab, a power station thirty miles from Karlson’s studio and the site of the US’s largest nuclear accident during the Cold War, and the Greifswald-Lubmin Nuclear Power Station located just over an hour east of her birthplace, which she visited on a tour last summer. While there, Karlson documented rooms lined with pipes and valves, dizzying scaffolded stairwells, hallways disappearing into darkness, and a control room that looked like something from a 1970s sci-fi movie. The photographic evidence of the accidents contains unidentifiable disorder, which serves as source material across her new body work. In these images, nuclear power, leveraged as propaganda to bolster a sense of national security across geographies, succumbs to the natural processes of entropy: a dissolving infrastructure evidenced by corroded pipes, sagging wooden frameworks, and crumbling concrete foundations.

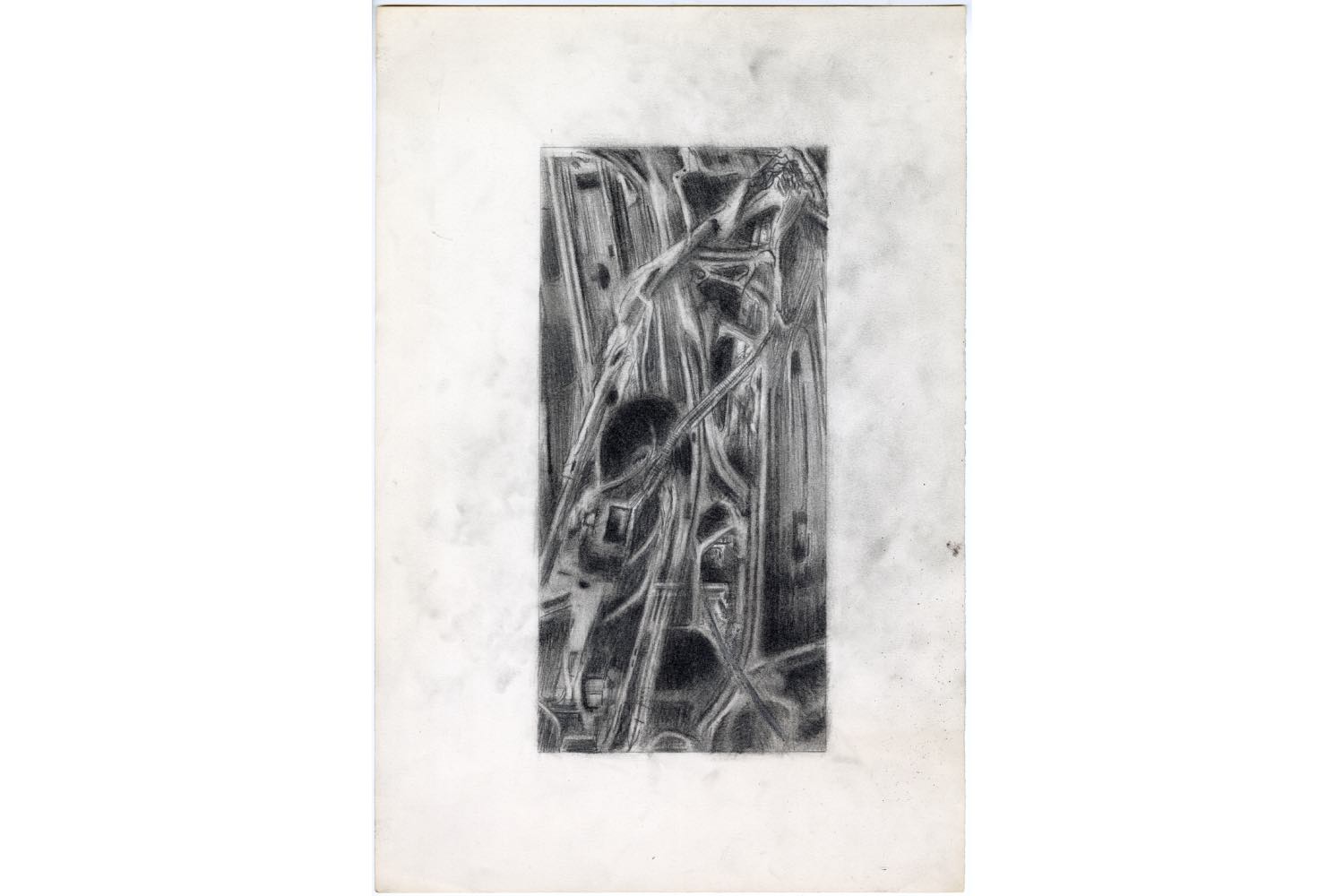

It’s not incidental that photography plays a central role in Karlson’s process. Since its inception, photography has been a fundamental tool for policing and forensics, and as such has been instrumental to systems of social control. In her drawings, Karlson distorts cropped inkjet reproductions of the photographs themselves, destabilizing their spatial logic while maintaining certain details. In Staub 4 (2024), for instance, she zooms in on a photo of deteriorating tubing and a rotted floor, reimagining a visual interruption in broken pipes as a site of reconfiguration. It looks like intelligent life or human intervention exploiting a faltering system. There’s no clear indication of up or down, and recognizable details are fleeting. Karlson’s drawings complicate our relationship to photographic technology, undermining its status as a “truth-telling” medium.

Karlson’s recurrent invocation of dust situates her in a historical dialogue with Georges Bataille and his circle of Surrealist painters. While the Precisionists and machine aestheticists of the 1920s fetishized machinery and glamorized factory production, Bataille critiqued it by centering the inevitable byproduct of natural decay and industrial production — dust and disorder. These elements became a model for Surrealist abstraction and its painterly decomposition that resisted the clean lines, sealed boundaries, and hierarchical order of capitalist production. In contrast to LA’s glossy veneer, Karlson drains her paintings of vibrant color and sometimes mixes her pigments with ash and particulate she collects around her studio, or scrapes the surfaces of her work with texturized patterns she observed in factory floors and the sidewalks outside. Oftentimes they are executed across two canvases, interrupting the illusory continuity of the image. Like Bataille’s Surrealists, Karlson’s paintings host disruptive noise in places where we might feel more comfortable with gleaming surfaces. These aren’t the sealed environments we’ve been promised in our technologically advanced cyborg fantasies.

They also don’t align with what we typically expect from a painting. Karlson bases her elongated canvas ratios on architectural features like fuse boxes in her studio or pipes in a gallery space. Sometimes she props them on the floor or integrates them into the wall, as is the case with Staub (Holes) 1 (2024), a long, thin painting that might be mistaken for the view into a boiler room. These gestures present paintings as both objects and windows into her worldscapes. “Painting is a pretty closed system,” she says in reference to her installations. “I’m trying to make room for randomness or openings, to make an artwork that is not as sealed as we would like to think. It’s like the attachment we have to stable ground.” Karlson refers here to the stable ground of the horizon line and linear perspective, optical constructs that create an illusory view of the central self and distant other. German and American Romantic landscape painting serve as particularly salient examples, with their sublime fantasies of natural purity untouched by foreign influence that became a visual and ideological resource for the German Nationalist agenda and manifest destiny of westward expansion. Karlson seeks to liberate the chaos and instability such worldviews endeavor to control.

To this end, Karlson embraces what Hito Steyerl calls “the perspective of free fall,” where our position is not defined by any one horizon line, but by relationships to the constellation of other bodies around us. “As you are falling,” Steyerl writes, “the horizon quivers in a maze of collapsing lines and you may lose any sense of above and below, of before and after, of yourself and your boundaries.”2 If it weren’t split across two canvases, we might imagine tipping over into the amorphous void in Karlson’s painting The Open (2024). Voids like these also appeared across Karlson’s 2022 show “Cypher,” where vacuous cavities based on x-rays of the artist’s body erode composite forms, recalling bone tissue or the interior contours of car doors in works like Vagus (2022). In yet another body of work, circular forms gape like eyes, mouths, or drains in Passage II and IV (both 2022). Karlson’s mechanomorphic visual vocabulary and affinity for voids put her in lineage with the artist Lee Bontecou, who created faceted sculptures and soot drawings against the backdrop of the nuclear arms race during the Cold War. “The natural world and its visual wonders and horrors — man-made devices with their mind-boggling engineering feats and destructive abominations, elusive human nature and its multiple ramifications from the sublime to unbelievable abhorrences — to me are all one.” Bontecou once wrote in an artist statement. Karlson’s work similarly untethers binaries of nature and machine, subject and object, living and dead.

The dislocation of agency and control runs central to Karlson’s project. One particularly generative referent the artist continues to return to is a 1988 documentary titled Bitteres aus Bitterfeld (Bitterness from Bitterfeld) shot illegally by environmental activists to expose dangerous levels of chemical pollution in its titular East German city. The guerilla video is as intoxicating as it is damning: long, slow pans of barren fields decimated from coal extraction appear extraterrestrial. Ochre froth collecting in public waterways dances to an avant-garde jazz score. The gaping black mouth of an open pipe leeches toxic sludge into a puddle near food processing facilities. The bad YouTube translation of the German narration casts the poisonous ooze as strangely animate: “Remains run out of the canisters and form sparkling puddles…the pipes often freeze, burst, and the broth runs uncontrollably.” What might have provoked nightmares for Caspar David Friedrich or Albert Bierstadt is no latent, discarded waste, but rather an active, bubbling agent of chaos wreaking visible havoc all over town.

Karlson’s practice urges us to confront discomfiting elisions between body and machine, human and nonhuman, objective truth and subjective interpretation. In her practice, this also manifests in frequent collaborations and exchange with artist peers across two-person shows and co-authored projects. Through her engagement with photographic material and the historical echoes of environmental and industrial collapse, Karlson punctures holes in dead space: the notion of a solitary artistic practice, fantasies of impermeable bodies, the boundaries of a painting, the validity of a photograph. Imbued with the visual language of decay and disruption, her paintings reflect the fragility and volatility of what we consider “sealed” systems. Karlson challenges the technological ideal of a seamlessly controlled world and makes room for new possibilities in the very cracks that we typically try to smooth over. Isn’t solid ground really just an accumulation of dust?