It’s 2013 in downtown São Paulo. On the rooftop of an iconic building on the margins of the infamous elevated highway known as Minhocão [Great Worm], a house party is taking place. Upon this old and precarious infrastructure, hundreds of people gather in improvised fashion surrounded by a 360-degree view of countless other constructions. Everyone is intoxicated by the dense atmosphere, within which all kinds of spontaneous and outlandish behaviors transpire; the party proceeds as negotiations continue with neighbors and the police, who try to stop the mayhem.

It’s 2013 in downtown São Paulo. On the rooftop of an iconic building on the margins of the infamous elevated highway known as Minhocão [Great Worm], a house party is taking place. Upon this old and precarious infrastructure, hundreds of people gather in improvised fashion surrounded by a 360-degree view of countless other constructions. Everyone is intoxicated by the dense atmosphere, within which all kinds of spontaneous and outlandish behaviors transpire; the party proceeds as negotiations continue with neighbors and the police, who try to stop the mayhem.

That feverish event, an experiment called Mamba Negra [Black Mamba], was the brainchild of Carol Schutzer and Laura Diaz. It came about at a time of manifest cultural and political effervescence in the city, with electronic music gaining strength outside of the club scene, and in a year marked by the largest demonstrations in Brazil’s recent history. (Starting with leftist riots against the increase in prices in public transportation, the movement ended up fomenting right-wing protests that eventually led to the recent impeachment.)

Schutzer (aka Cashu) and Diaz (aka Angela Carneosso), with backgrounds in architecture and cinema respectively, have long been involved in music production — Cashu as a much-respected and in-vogue DJ, and Diaz as a singer and musician in the band Teto Preto. Having spent time as part of the Voodoohop collective — one of the most notorious and active groups in the underground party and art scene at the time — they resolved to concoct something new out of their experiences.

Voodoohop’s activities profoundly marked the social imagination of the Brazilian cultural underground. By coordinating multifarious musical acts with performances and VJ’s, they developed a highly specific style. It may be easier to think of their endeavors as “happenings” rather than merely parties or music festivals. By combining European techno with neo-tropicalismo, urban buoyancy with psychedelic trips, site-specific occupations with Dada-like manifestations, they stirred up an unruly, multicolored melting pot, with blowouts both ludic and full of energy.

In the first instance, a number of other party collectives, such as Capslock, Calefação Tropicaos and Gente Que Transa, appeared alongside Voodoohop. A couple of years following Voodoo’s first enterprise — a small and unpretentious party at the legendary Bar do Netão — Schutzer and Diaz had the idea of fostering Mamba Negra. Central to Voodoohop’s concept was their relationship to the streets and the dusty structures of São Paulo’s Centro. Materializing in the midst of a cultural revolution, a number of different collectives began occupying the streets and organizing open parties at overlooked public locations in the downtown area with the intention of setting themselves free from the social and economic restraints imposed by the established cultural scene. While transcending the restrictions of the prevailing club culture, these actions sought to reimagine the political and social relations between neglected public locales and the inhabitants of the city. Moreover, these urban occupations revived Carnival’s capacity to reclaim the streets as a socially active and artistically engaging terrain.

Downtown São Paulo is a sprawling landscape marked by a combination of colonial buildings and the residues of modernist urban planning. One is confronted by the realities of its impoverished inhabitants: squatters, street dwellers and the recent influx of immigrants, as well as the latest evidence of gentrification. Like many other global urban centers, São Paulo has seen considerable suburban growth coupled with municipal expansion. The ongoing neoliberal strategy of renovation and real estate speculation has significantly reconfigured the inner city over the past few years, causing the bigger parties to relocate to more peripheral spaces, commonly such former industrial neighborhoods as Brás and Mooca. This has led to parties at junkyards, a former milk factory, as well as large abandoned warehouses.

It is a trope of artistic occupations and interventions throughout history that they are eventually capitalized by the very economic forces against which they were originally set. Gentrification, by and large, follows the movements of the art community and cannibalizes its achievements. Although this narrative might have applied to the once-booming Brazilian economy, the deepest recession in decades means that party organizers will struggle in the future to secure public financial backing for the open street events. However, Mamba Negra has tried to balance the number of open and paid-for events, despite the corollary financial challenge.

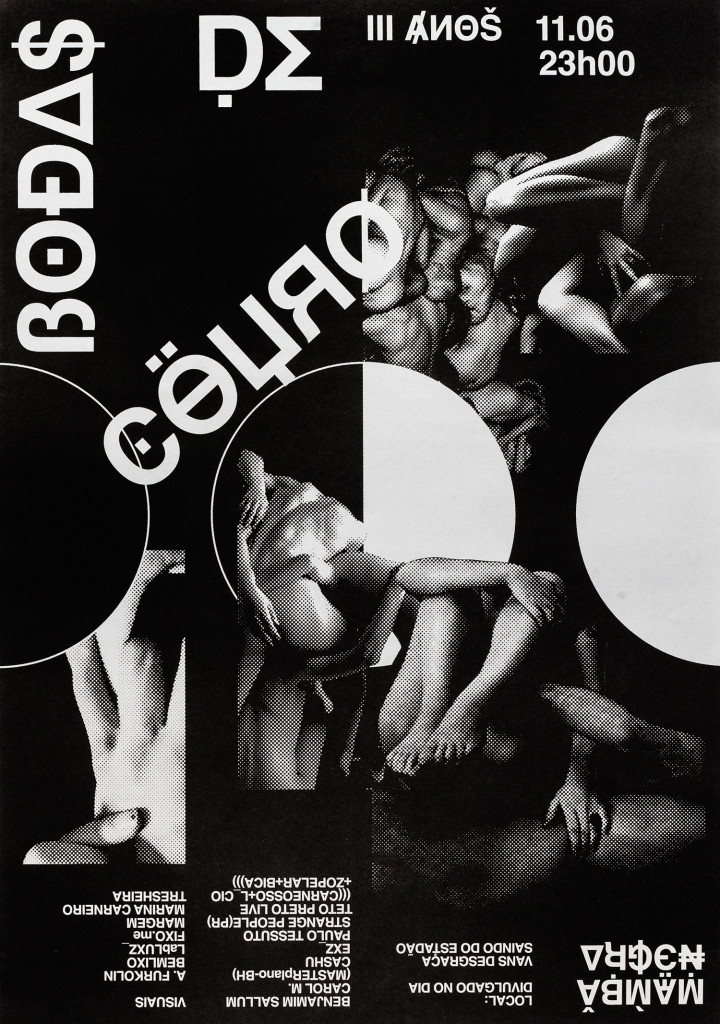

The parties rapidly grew, from that first rooftop get-together of around three hundred people, to events of around one thousand at Cine Marrocos, an enormous, lush cinema space, which has been squatted, along with the twelve other floors of the building, since 2013. At present, Mamba parties attract numbers in the region of fifteen hundred, and Mamba itself has also expanded into Radio Virus as well as a newly founded music label, Mamba Rec. Embodying its creator’s vigor, Mamba is essentially radical in character, shaped by fierce humor and a solid political backbone. Their engaging visual identity, designed by Estúdio Margem, is admittedly bold in its creations, both satirizing and commenting on social issues spanning from violence and criminality to freedom of gender and sexuality. In Schutzer and Diaz’s words: “Mamba is, before everything, an opening. The city is our arena. Through its festive facet, Mamba has the potential to articulate and test cultural, social and moral issues… Our role is to deal with these polemics through our language, production and acts. These factors alone activate the discussions, which allow for the creation of the conditions for sexual, cultural and political freedom.”

While most of Voodoohop’s events might be defined as a form of contemporary hedonistic ritual, Mamba operates in more dystopian terms; although dreamlike for the most part, they are less like sites where anything is possible than they are spaces where anything is permitted. From the midnight hour into the morning and into the new evening, people dance ecstatically while enraptured in a near-apocalyptic diegesis. If chaos and death are already upon us, we might as well embrace them, one might say. Both sensual and murderous, there isn’t a better analogy than that of a serpent attacking its prey: just as the snake moves in agile and acute ways, it is also lethal — everyone is trapped.