Race, resistance, rage, rebellion — words that are presently etched into the forefronts of everyone’s mind. As cities burn, glistening with the fire of destruction that is almost always a result of endured pain and catastrophic silence, hashtags trend, funds are redistributed, and statements of virtue are published. We march, cry, yell out for our mothers, we repeat the words that we have expressed so many times before: “I can’t breathe.” And it is true both literally and figuratively. George Floyd, Eric Garner, and Sandra Bland, quite literally, could not breathe. But the rest of us are also breathless. Always struggling to be heard, or to survive. Existing in a limbo that depends on our theoretical knowledge of what it means to be free and our simultaneous lack of freedom in any proximate reality. Thus, revolution is the logical response.

Our world is in a period of awakening to collective struggles and to oppression that disproportionately and systemically steals the joy and the lives of black, indigenous, and trans people. To exist as a black person when blackness of the body, mind, and soul has been made a crime carries a heaviness, a weight that no amount of solidarity can relieve. A pressure that many cannot find the words to describe, therefore internalizing that which the world is only just beginning to realize. When black death and suffering turn profits and a black person is at equal risk of being killed on Black Lives Matter Plaza as on any other street, where does blackness lie down to rest?

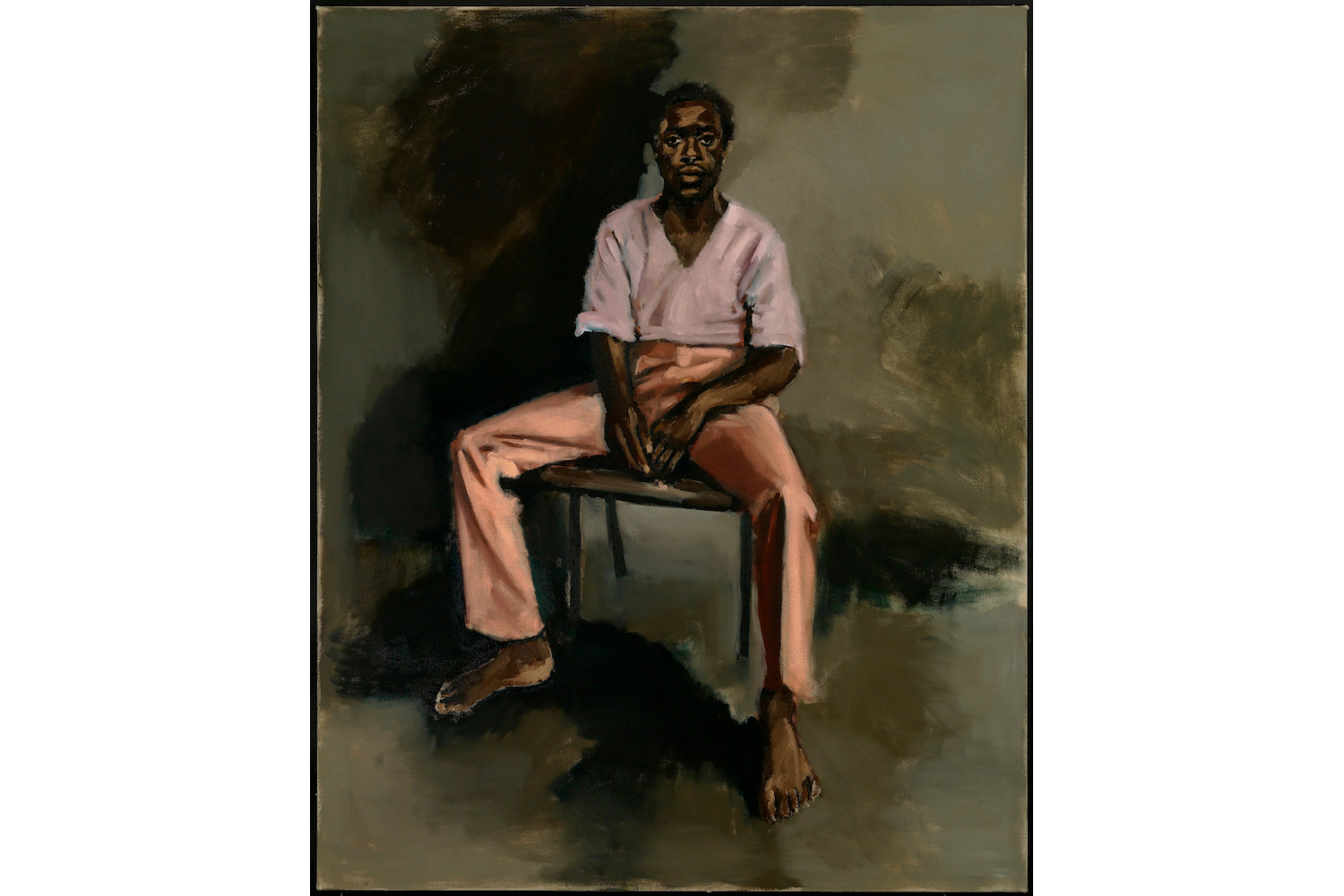

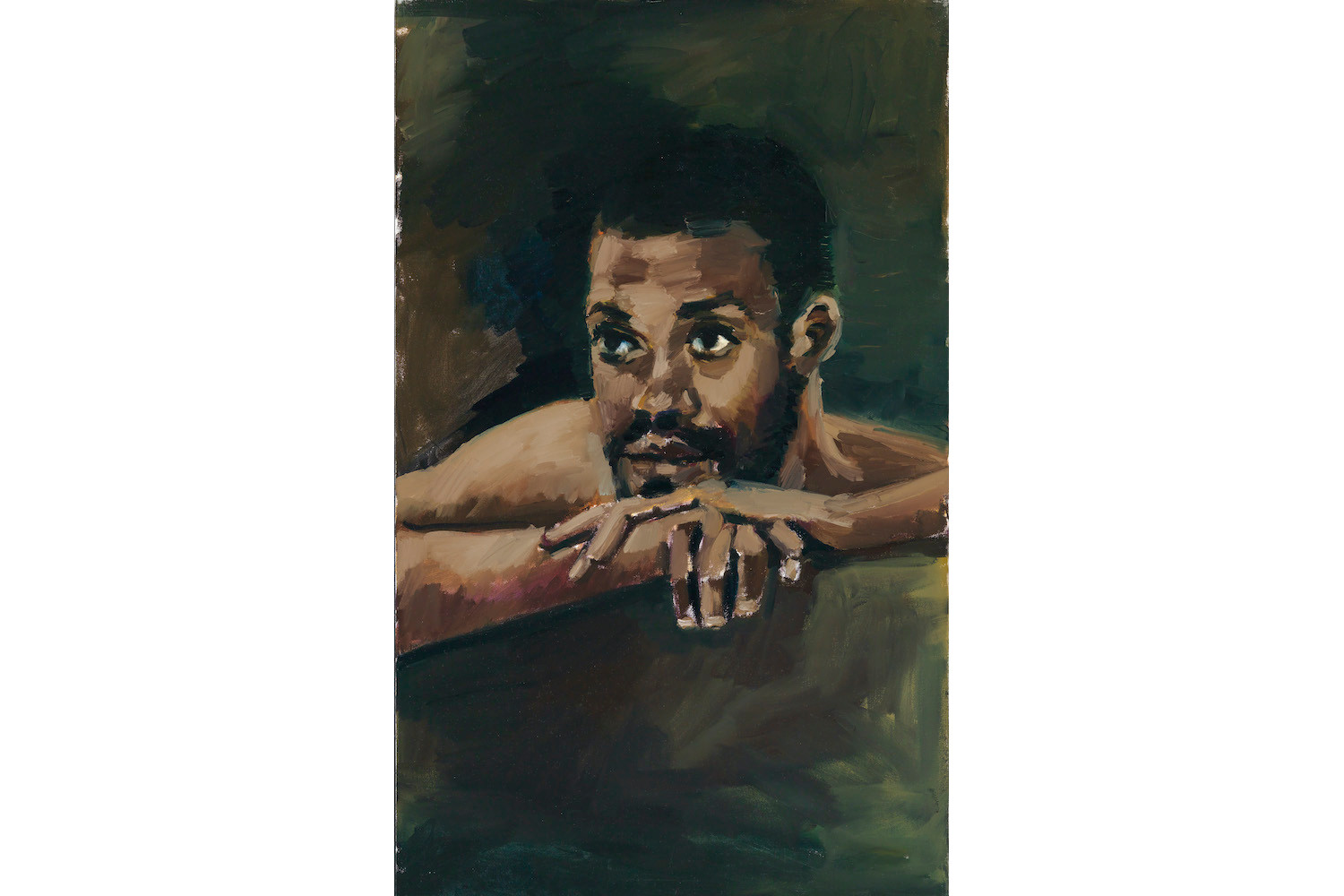

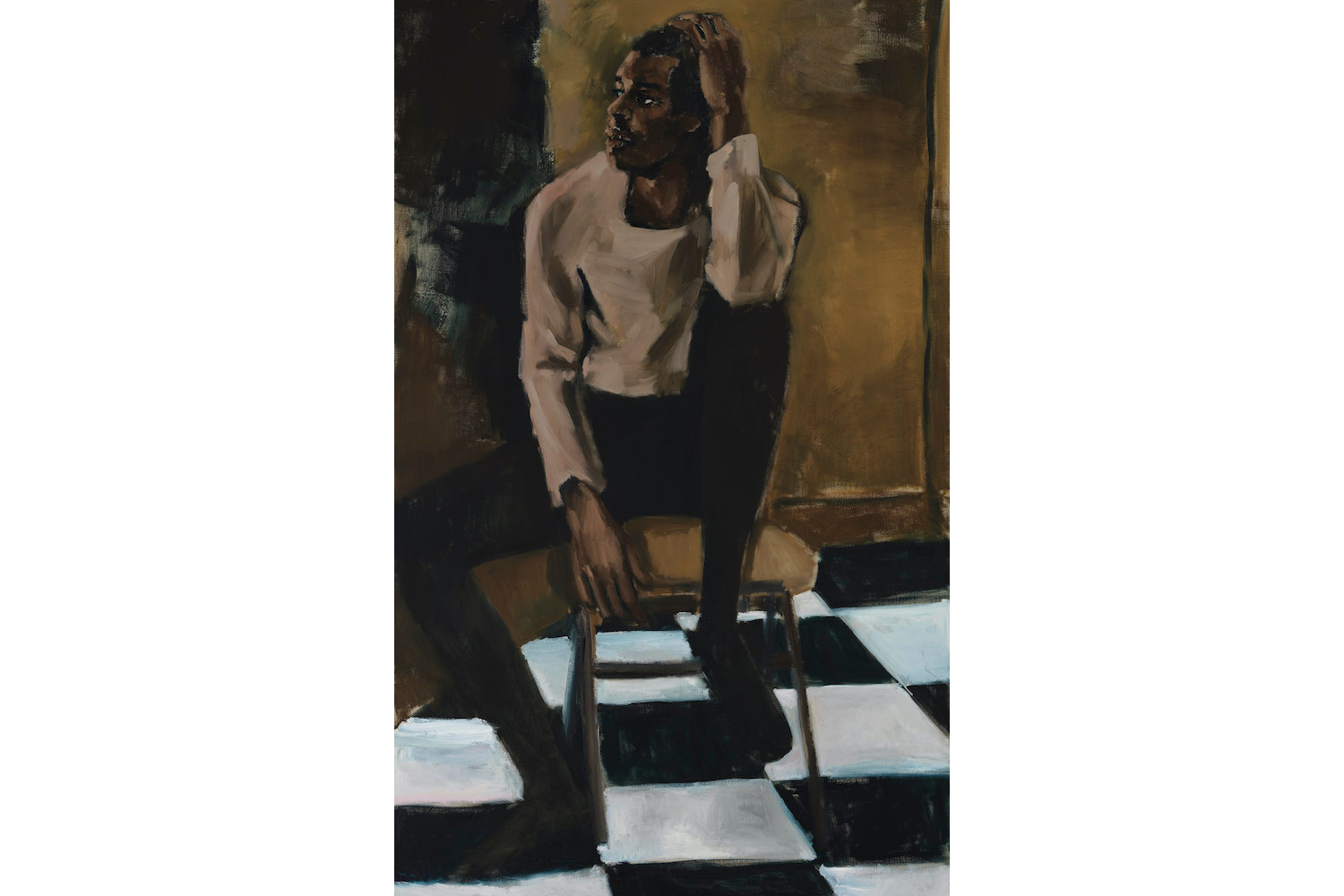

Submerged in thought, or perhaps focused on something invisible to us, a painted black figure rests his head in one hand, propping up his knee to relieve the solid weight of his upper body. The collapse forces the figure forward and into our conscious imagination. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s painting Medicine at Playtime (2017) evokes the portrait of a man we once knew. A brother, friend, cousin, teacher, and, depending on our own age, a father. Yet the title of the work obscures this reality from our interpretation. His casual yet confident posture tells us no more of his life, his work, his family than the subtle familiarity of black-and-white-checkered tile or brown washed walls that frame his seated body. Meeting this work wholly requires us to combat our collective desire to define a life around a specific set of actions — positive and negative. It requires us to embrace stillness as central and fundamental to our being. To release our expectations of that thing which is so feared and often misrepresented in our society: our blackness.

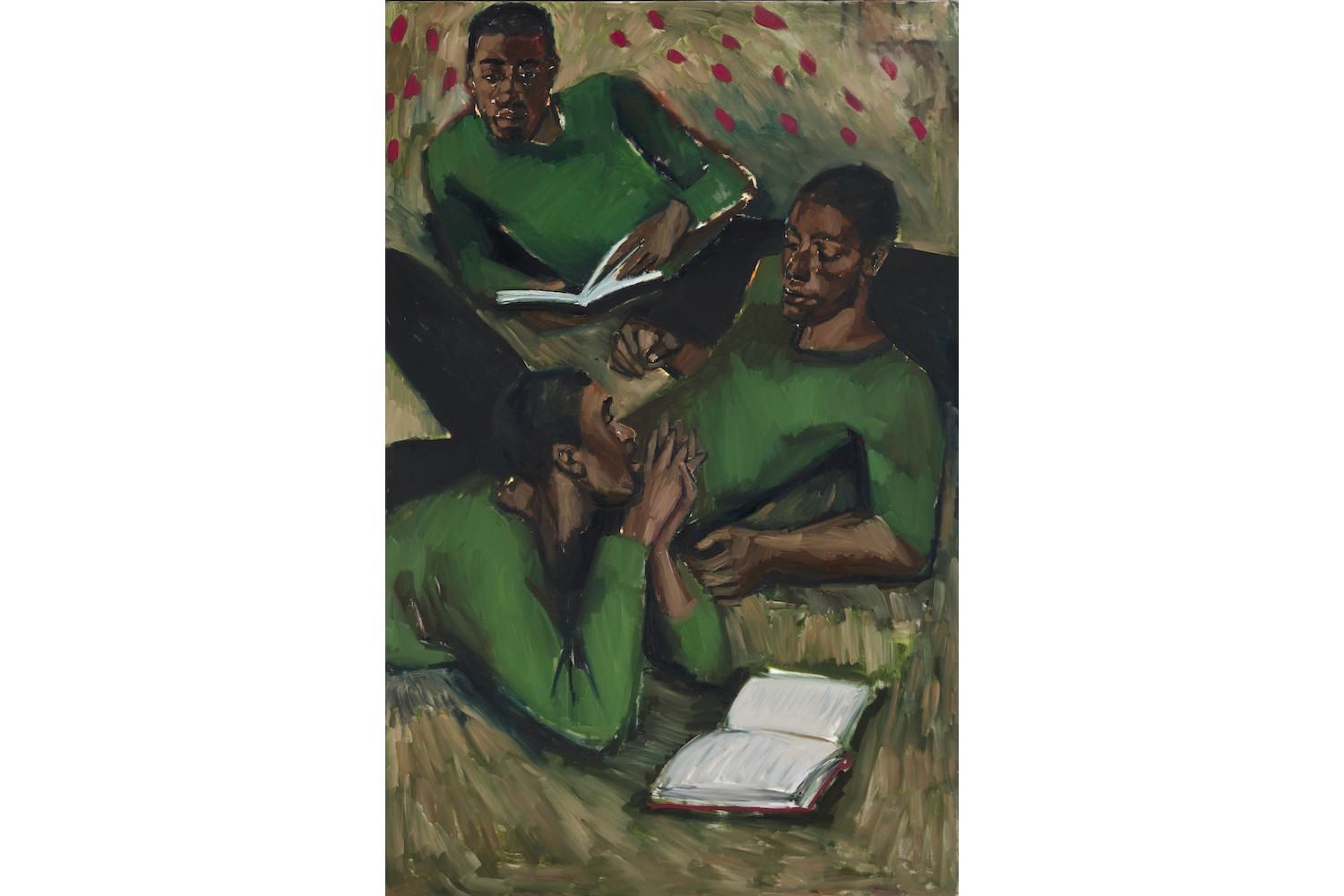

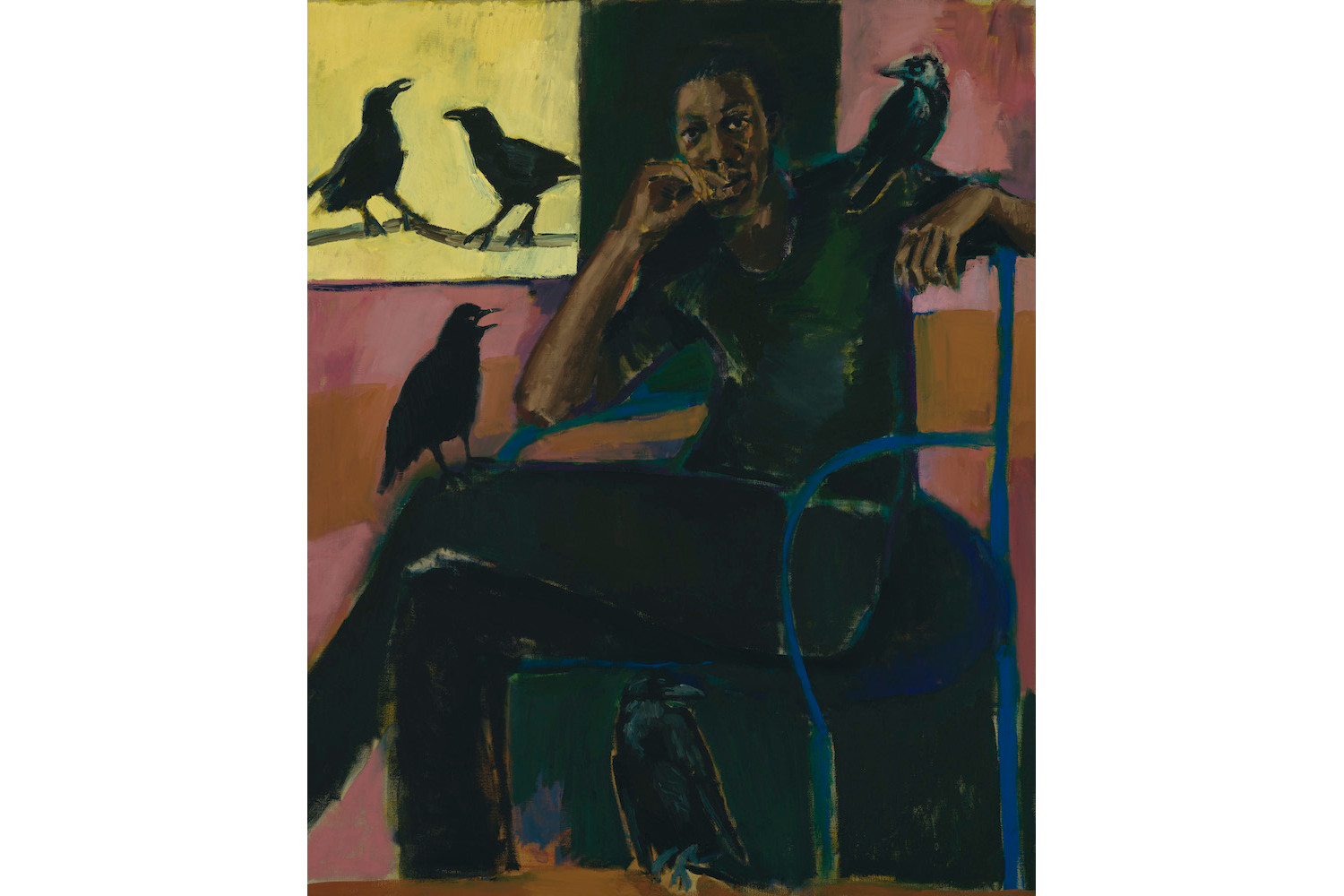

With acuity and simplicity, Yiadom-Boakye reveals the multifaceted reality of blackness. Her subjects make visible the invisible reality of being in a black body: the reality that is often shielded in portrayals of blackness in the news, films, music, and broader pop culture; and in the worst cases, it is stripped away. Leisure and life are denied broadly and systemically. A world that makes it its goal to disappear black lives requires art that affirms black lives. Yiadom- Boakye’s work removes itself from the brutality of our physical reality and asserts another dimension in which blackness is not crime, nor discomfort. Neither struggle, nor statement. Instead, blackness is a state of being punctuated by thoughtfulness, reflection, intimacy, community, and repose. In a world where countless images of black bodies exist as brutal evidence of pain and suffering and are circulated without regard, Yiadom-Boakye’s conscious decision to create images of black bodies in moments of atemporal pleasure and tranquility is cathartic.

There is a necessity for new and different representation of the black body grounded in futurity, which Lynette Yiadom-Boakye fulfills through her timeless scenes of black life. Her work visualizes an alternate space where black bodies can exist undisturbed and undefined by contemporary or historical sociopolitical landscapes. Perhaps the figures that Yiadom-Boakye constructs from the annals of her mind, and our reality, could once be considered fictive. But today, their striking dimensionality and foresight rings generative, or even speculative. Although sometimes bordering on fantastic, the works that resonate strongest here — those like Medicine at Playtime (2018), Repose 1 (2015), Sister to a Solstice (2018), and To Reason with Heathen at Harvest (2017) — feel too close to our world to exist solely as evidence of another. In them, there always lingers a glance unmet; one too confident to be fortuitous; a head turned away with body front facing still; an ear poised to listen; an arm hoping to embrace; an image of a black man lying, leaning on his elbows, eyes cast down in thoughtful contemplation or reflection. A woman smiling certainly at her companion, another anticipating arrival. A revolution waiting to happen. And yet, the image appears so distant from our reality as to produce a startling effect. For me, viewing this work for the first time and thereafter felt like a wakeup call — or better, a call to action.

But futurity is frequently complicated by political nuance, bound by a collective imagination that acts like a multi-headed beast of the same body. The freedom we desire is distorted by semantics, identity, and by the presence of oppressive systems in our everyday lives. Yiadom-Boakye’s composite figures remind us of the simplicity and truth of our end goal — liberation — and more pertinently, how intrinsic our humanity is to the struggle. Her eidetic paintings, in this sense, embody the powerful employment of the black radical imagination in the visual arts, to enlighten viewers to a black queer feminist futurity by drawing attention to our own chaotic state of unrest and preoccupation. Contrasting, and thus challenging our present reality, Yiadom-Boakye reassures us that revolution is possible. But most saliently, her work asserts that revolution will be pleasure-centered.

Adrienne Maree Brown, a celebrated scholar whom I deeply admire, compared organizing to science fiction because by organizing our communities “we are shaping the future we long for and have not yet experienced.”1 In her recent book Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, Brown teaches that a revolutionary politics that centers pleasure positions us closer to freedom. When considered through a black queer feminist lens, contemporary artists play a significant role in the fight for justice. Visual artists are capable of imagining and communicating a future that does not currently exist for all people. A world in which rest and joy are possible and essential for all people, but especially for marginalized people. Yiadom-Boakye projects a world where gathering is encouraged and leisure is expected of black people — as opposed to a world in which we are subjected to violence for doing so. The world that she depicts in her paintings is absent of racist, capitalist, patriarchal structures, and institutions that rely on the oppression of black people. Her subjects do not have to fight, protest, or march for the right to be. The blackness with which she imbues her subjects warrants no explanation, no justification, and no defense. They simply exist in the abstracted utopia of the canvas, washed in vibrant color and quiet poeticism, mirroring a future to which we are entitled but have not yet achieved.

The works of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye are assertions that black joy exists in rest, in dance, in leisure, in reflection, in solitude, and in comradery. When the world can only see sadness and despair, Yiadom-Boakye’s speculative figurations demand an acknowledgment of black joy as resistance. If the role of the artist is to imagine a world that is on the precipice of existence, then our role as viewers, scholars, critics, collectors, curators, and patrons of the arts is to fan the fire of resistance, which moves us closer and closer toward justice. The great intersectional lesbian feminist Audre Lorde declared that the personal is political. When anger demands too much of our bodies, we must remember her life and words as epitomized by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s idyllic paintings, and we must rest.

Today I rest, and in my reflection, I remember the countless brothers and sisters whose lives were taken from them. Gone too soon, I pray their souls have reached the eternal peace denied to them in life. I remember their names as I rest, and as I fight. Breonna Taylor, Oluwatoyin Salau, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, Riah Milton, Tony McDade, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks — I write this for you in hopes that I can honor your memory in the only way I know how.