“Allow me, then, as we part company at this threshold [barzakh], to break the contract between one absurdity and another.”1 –– Mahmoud Darwish, In the Presence of Absence

Two signs, affixed to the entryway of Kunsthalle Basel’s upstairs galleries, set the stage: “WARNING: This area is under 24hr surveillance.” Adjacent to the entrance, a laser refracts its beam across the museum’s courtyard. Though its function is not yet clear, it portends the unsettling fact that one is being watched upon entering Lydia Ourahmane’s Barzakh (2021), the Algerian-born artist’s largest, most intricate solo exhibition to date. The eerie feeling produced by the supposed presence of continuous surveillance momentarily subsides upon registering the contents of Ourahmane’s installation: a fully reconstructed apartment, replete with the warm mahogany tones of old furniture, inviting leather couches, two chandeliers, a bed, kitchen appliances, and cupboards topped with books and filled with the meaningful detritus of everyday life. Yet after traversing the space, making oneself proverbially at home and succumbing to the tacit provocation to open drawers and survey the objects with increasing scrutiny, the sense of uncanniness creeps in.2 With no walls separating the domestic environment’s evoked rooms, its cozy familiarity is undone at the seams. The viewer becomes a trespasser, at once surveilled by Ourahmane’s exhibitionary system but also enacting surveillance by rifling through the inventory of a life seemingly interrupted or left unlived.

“The house,” Gaston Bachelard famously wrote, “is a ‘psychic state,’ and even when reproduced as it appears from the outside, it bespeaks intimacy.”3 Ourahmane’s Barzakh is an exploration of the psychic states and intimacy associated with the notion of home, engendered by the reproduction of an actual house. To construct Barzakh, the artist physically shipped the entire contents of her apartment in Algiers to Basel, where she reassembled it from memory and rigged the installation with two systems of sound-based surveillance. The exhibition follows Ourahmane’s singular working method: the artist devises conceptual propositions rooted in concrete contexts and oral histories, most often regarding Algeria. Their site-specific actualizations unleash logistical absurdities and bear profound bodily and geopolitical consequences. The artist’s sparse, sensorially arresting installations teem with colonial presences and resound the intimate frequencies of home and exile.

Ourahmane attends to the affects and politics of displacement across space and time as she forcefully decontextualizes the objects that become her artworks. In p.H. 8.7 (2015/2018), for instance, the artist smuggled soil from Algeria and scattered it on gallery floors in Europe. In The Third Choir (2014), she assumed the bureaucratic challenge of shipping twenty empty oil barrels from Algeria to Europe — the first artwork to legally exit the country since its independence in 1962. By divesting objects of their quotidian functions, Ourahmane animates them into exerting the durability and pressure of their colonial histories. Coordinated by Ourahmane’s friends and fellow artists in Algiers upon her inability to return to Algeria amid its pandemic-induced border closure, the unseen shipping at the heart of Barzakh is a monumental act of dislocation in all of its connotations: the disturbance of a proper or original state, the expropriation of location, and the disarticulation of the body. Yet the precarious transformation of an apartment’s holdings into an art installation paradoxically heightens its objects’ intimate charge by making radically public the physical remains of private lives and sedimented histories.

The apartment that Ourahmane occupied upon returning to her homeland several years ago was built in 1901, one of the first buildings that the French commissioned in their colonial renovation of the center of Algiers. In its angularity, symmetry, and fin-de-siècle façade, the apartment exemplifies colonial urban planning’s domineering territorial imposition. A century later, its exterior has witnessed the ongoing anti-government protests that have stunned Algeria since 2019, whose revolutionary fervor has outlasted the reactionary banning of street marches in the pandemic present.

The apartment’s prior inhabitant was an Algerian woman who previously lived in Germany during her marriage to a German man. Within their divorce settlement, the woman kept the household objects of their postwar German life. Accompanying her return to post-Independence Algeria, these objects were left untouched after her death and furnished the apartment that Ourahmane rented. The woman’s inability to part with the domestic interior of her former life forms a striking parallel to the psychic structure of melancholia, whose afflicted subject cannot overcome the loss of an object, person, or nation.4 Their unassimilated grief endures. The melancholic remainders into which Ourahmane habituated her everyday abound in Barzakh — from half-melted candles and an ancient package of Frischhaltefolie (plastic wrap) to the delightfully kitschy painting of an Alpine landscape to which the artist dedicates its own room behind the Kunsthalle’s main gallery. Such an image typifies a clichéd Germanic vision of Heimat, an idealized national homeland, already irredeemably lost.

In Barzakh, the remnants of the woman’s life become intimately intermixed with Ourahmane’s possessions as the histories encoded in their lives uncannily intersect. The reassembled apartment radiates what the postcolonial theorist Ann Laura Stoler termed “imperial duress” to describe “the durability and distribution of colonial entailments that cling … to the present conditions of people’s lives.”5 Imperial duress, writes Stoler, comprises “the hardened, tenacious qualities of colonial effects; their protracted temporalities … a pressure exerted, a condition borne in the body.”6 The objects in Barzakh overflow with imperial duress by unhousing specters of indiscrete violence — French colonialism and its traumatic aftermath in Algeria’s war of independence, its fervent anticolonial nationalism, the factionalist violence of its Civil War up through present crises of political corruption and migratory exodus. They form an oblique portrait of what Algerian novelist Assia Djebar called “the long and abiding state of morbidity in which Algerian culture has lingered … a future bled white.”7 Through the multisensory, quasi-forensic experience of intaking the artist’s apartment — gazing at the spines of her myriad of books, sinking into her couch, inhaling the perfumed scent of her bathroom cabinet — the viewer’s body becomes intimately implicated in the colonial residues inscribed within the objects themselves. In doing so, Ourahmane dislocates her predecessor’s objects of private melancholia into a public scenography of colonial melancholia. Her installation claims a melancholic ethics of refusing the amnesia of coloniality’s ongoing damage by reverberating its spectral presence outward onto the unwitting bodies it covertly encounters.8

In her book Algeria Cuts: Women and Representation, the postcolonial critic Ranjana Khanna centers “the cut” as the privileged figure of colonial violence in the art and literature of modern Algeria.9

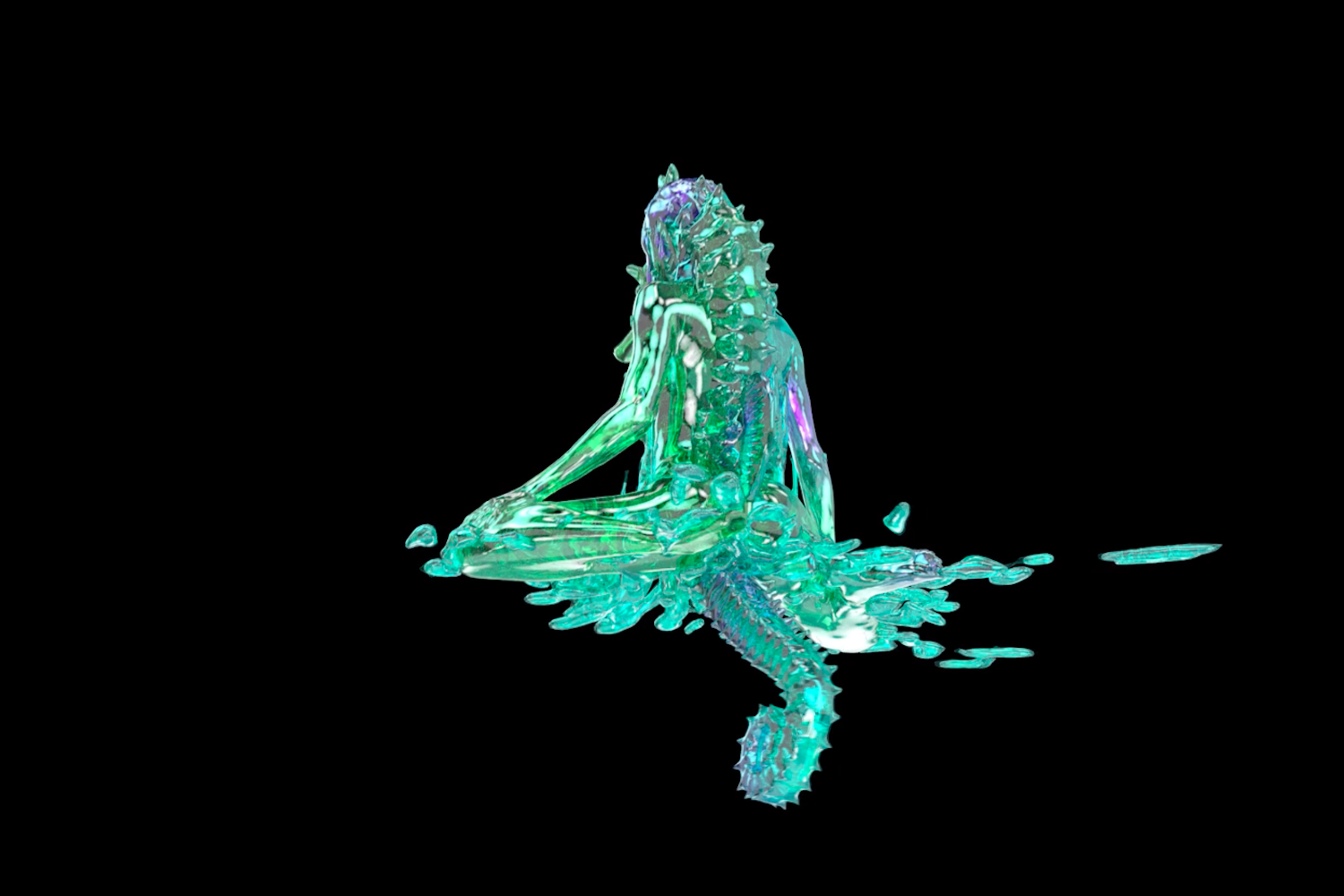

Khanna foregrounds the cut not only in terms of colonialism’s gendered injury and traumatic wounds, but also in its filmic connotations, as an aesthetic device that splices together discrete spaces and times beyond the frame. The cut repeatedly appears throughout Ourahmane’s practice as an inscription of imperial duress, piercing together disparate histories of violence. In In the Absence of Our Mothers (2015–18), the artist surgically implanted a gold tooth into an extant gap in her mouth, a gesture that conjoined her family history of anticolonial resistance to contemporary crises of illicit migration. In 1 decade of hair (2019), the artist cut off her braided hair, releasing the remains of a bodily archive. In صرخة شمسية Solar Cry (2020), she tattooed a woman warrior, an image from a Neolithic rock carving in the Algerian Sahara, into her skin. The proliferation of cuts in these former works enable the apartment’s dislocation in Barzakh to come into view as one momentous incision. They moreover evince what is different in this latest work, that the site of the cut has been displaced from the artist’s own body onto the ambivalent spaces of home and nation.

The central focal point of Barzakh, the two doors to Ourahmane’s apartment forcefully cut across time, adjoin overlaid histories by way of their extraction. The first wooden door is the apartment’s colonial original; the second metal door was added in the 1990s to reinforce protection amid the raids and disappearances of the Civil War. The two doors bookend a century of violence and expose “the systematic disposability of bodies in struggles for sovereignty,” in both Algeria’s colonial and contemporary contexts.10 The violence of the doors’ dislocation is evident in the remains of the brick wall adhered to the doorframe, its chalky red evoking an injurious cut into bodily flesh. The two doors’ nine total locks bear witness to an excess of fear and false security against an enduring external threat whose identity changed over time. By extricating the door-pair from its function as the apartment’s border and threshold, Ourahmane releases it from the weight of its duress as “an object of fear.”11

The two technologies of surveillance in Barzakh further cut across time. The sheer presence of surveillance harks back to a colonizer’s objectifying gaze. Such optical domination was canonically represented in another artwork set in an apartment in Algiers, Eugène Delacroix’s Women of Algiers in their Apartment (1834), whose art historical specter haunts Barzakh. In the orientalist painting, the French painter’s voyeuristic surveillance of Algerian women is synchronized with his spatial trespass into and implied erotic conquest of an apartment’s concealed harem. Ourahmane’s installation counters Delacroix’s Algiers apartment by presenting the concrete material remains of the violent system that produced and idealized such orientalist fantasies. Yet the durable presence of surveillance in both reveals the colonial reason through which certain bodies were and remain objectified and targeted, which continue up through today in new border regimes of global “security.”

The first system of surveillance in Barzakh is comprised of bugging devices. In these uncanny sculptural assemblages, Ourahmane has hidden listening technologies under elongated blown glass covers that noticeably stick out from the furniture on which they rest. The bugs surveil viewers by ominously registering any sound or conversation that takes place in their vicinity. Each one is given the title of a Swiss phone number, and anyone can eavesdrop into the space by calling the number and listening to the sounds that the devices perceive. In the second system, two laser beams are rigged to intercept atmospheric sound from the museum’s exterior. The light beam translates visual disturbances into the installation’s soundscape of white noise, which tactilely vibrates from transducers embedded in the apartment’s furniture — a technology that the artist repeatedly employs. The surveillance soundscape creates a space of relations as its acoustic vibrations intimately traverse between the furniture and the viewer’s body. By staging encounters with surveilled sounds, Barzakh unfixes the bodily borders of public and private, forging intimate echoes across the temporal bounds of colonial pasts and securitized presents.12

In the name Barzakh, Ourahmane recasts her apartment’s unhousing across space and time. The Arabic word’s many connotations include “barrier,” “separation,” “threshold,” “the grave,” and “isthmus,” a strip of land between two seas. In its most frequent translation as “limbo,” barzakh conjures the mystical boundary between humans and spirits, where specters await the judgment of their deeds in life. Through her act of intimate dislocation, cutting the apartment from its historical armature, Ourahmane releases its status of home into a vulnerable state of limbo that resounds its specters of violence in the here and now. Her objects await the judgment of their imperial duress, calling out for justice as we sense, surveil, and break the contract with their colonial presences.