Through their recent films, installations, and research, Lucy Beech investigates the dreams and troubles of matter in flux, sharing visions and gestures, and bodies and infrastructure that tend to remain invisible to most. Paying attention to what has otherwise been hidden and disguised for centuries — from human and nonhuman reproduction systems to waste management procedures — the artist-filmmaker tells stories that question preservation, reproduction, and disposability within the biopolitics and economies of contemporary societies.

Sewage systems, processes of assisted reproduction, viscous substances, and micro and macro assemblages of beings, organisms, and machines are brought together by Beech. The works merge the traditions of investigative filmmaking with the sonorities and rhythms of spoken word and poetry and the density of installed environments. This conversation anticipates the artist’s exhibition at the New Museum in New York later this year. Beech discusses their collaborative, research-based work methods and their interests and references while discussing recent projects, artworks, and exhibitions.

Filipa Ramos: Your practice is profoundly polyphonic, and so I would like to start this conversation by bringing in another voice. In her book Slime: A Natural History (2021), Susanne Wedlich gives an account on how viscosity shapes life and connects individuals (human and non), bodies, and landscapes. There’s a quote of hers that resonates with your work:

We are all creatures of slime, but some of us are more creative than others: there is a menagerie of oozing organisms to be found in all the world’s habitats, frequently changing these environments to suit their needs – by leaving their glistening marks. It may also be a surprise to discover that microbes were not only the dominant, but also the only form of life on Earth for billions of years, with slime, as the éminence gluante, propping up their power and setting in motion processes across the globe which still shape it today.1

It made me think about how your work considers the dynamics and flows of fluids, revealing how liquid and viscous matters make and unmake all sorts of bodies. Where does your interest in these soft and viscous matters, and states of matters, come from?

Lucy Beech: I like starting with this quote. In fact, I titled a recent show at Kunstinstituut Melly “Ooze” (2023). I’m fascinated by how fluid dynamics shape contemporary life. Viscosity — a fluid’s resistance to flow — can be a way to think about control, friction, and the management of bodies and substances. I remember first seeing Arthur Worthington’s early high-speed photographs from his 1895 publication The Splash of a Drop in Lorraine Daston’s book Objectivity (2007). He froze the fleeting moment of a splash of water falling into milk, making visible something previously imperceptible. Before these images, scientific drawings had idealized the splash as perfectly symmetrical, and in the book, Daston goes deep into how these images reflect cultural ideals. The camera, for all its technological advances, offered only a fragment of the fluids’ story. This interplay between unity, fragmentation, and multiplicity, or between fluidity and containment, resonates with broader questions of identity that I’m interested in. How do we define subjects in flux? And what is lost when we impose rigid boundaries on what is, by nature, dynamic and transformative?

For centuries, Western ideas about human “progress” have been tied to controlling and managing fluids, often through rigid systems of containment, whether it be sanitary systems, medicine, or even scientific representation. Drain systems and sewers are markers of modernity, but they also reveal a deep cultural anxiety about fluidity. Historically–in Greek philosophy, for example–identity and the body were understood as being in flux and tied to the flow of humors, energy, and matter. As scientific paradigms shifted, so too did the Western view of the body. Modernity sought stability and boundaries, reimagining the body as a closed, controlled system. Fluids — whether it is blood, bile, sweat, or urine — became either valuable only for their utility or dismissed as waste once separated from the whole. A lot of my work revolves around deconstructing these ideas, exploring how something is valued once it’s removed from its original purpose and how this is entangled with historical shifts away from fluidity.

Worthington’s photographs were hailed as scientific precision, but they were not neutral. Like all representations, they were shaped by the observer’s choices: the framing, the staging, the experimental setup. This paradox of fluidity and its representation is still on my mind, as is the inseparability of fluids from the frames used to define them: aquariums, glass plates trapping samples on microscopes, or concrete wave channels for studying fluid dynamics. These human framing mechanisms turn the wild, dynamic qualities of fluid into something orderly and comprehensible.

FP: This process of domestication of bodies and fluids set in place during the consolidation of modernity served political, scientific, and religious purposes: the control of people’s intimate lives, from health to sexuality. It also supported governance and commercial goals. This is made clear in a previous film of yours, Reproductive Exile (2018), which gravitates around the surrogacy industry. In relation to it, Sophie Lewis notes how “commercial surrogacy, albeit a work-around, is not, of course, interested in a communal, polymaternal unfixing of definitions of motherhood at all: in fact, it could not exist without a fixed definition of motherhood.”2 In parallel, Out of Body (2024) — your film for the New Museum commission — also explores the often hidden connections between biological and infrastructural matters. How do you see your work engaging with capitalism’s appropriation of and profit from organic processes?

LB: I’m interested in engaging with material realities that are difficult to perceive or hard to access. I love Roman Coppola’s music video for Daft Punk’s 1997 song Revolution 909, which starts with a rave being shut down and shifts into an unexpected backstory about the origins of a tomato stain on a policeman’s clothing, tracking a moment in time back through food production and labor to expose the hidden networks of capitalism. In a way, my recent work riffs on this tracing waste that ends up in deep geological salt cavities or the hidden urine collection programs that supply fertility pharmaceutical production. I pay attention to these processes as overlapping systems with economic, embodied, and environmental consequences and histories. These material realities are always forced out of view, underground, behind factory walls, and only within reach of those doing the physical labor. This necessity to obscure waste from view seems to come back to the fantasy of the body as a static structure with boundaries and edges. Here, purification is a way to keep the body intact — but, as I explore in my film Out of Body, this relies on the labor of others/technologies. I want to explore the body as a site of constant movement and transformation, and expose purification as partial and interdependent. In the end, everything passes through something else to continue existing.

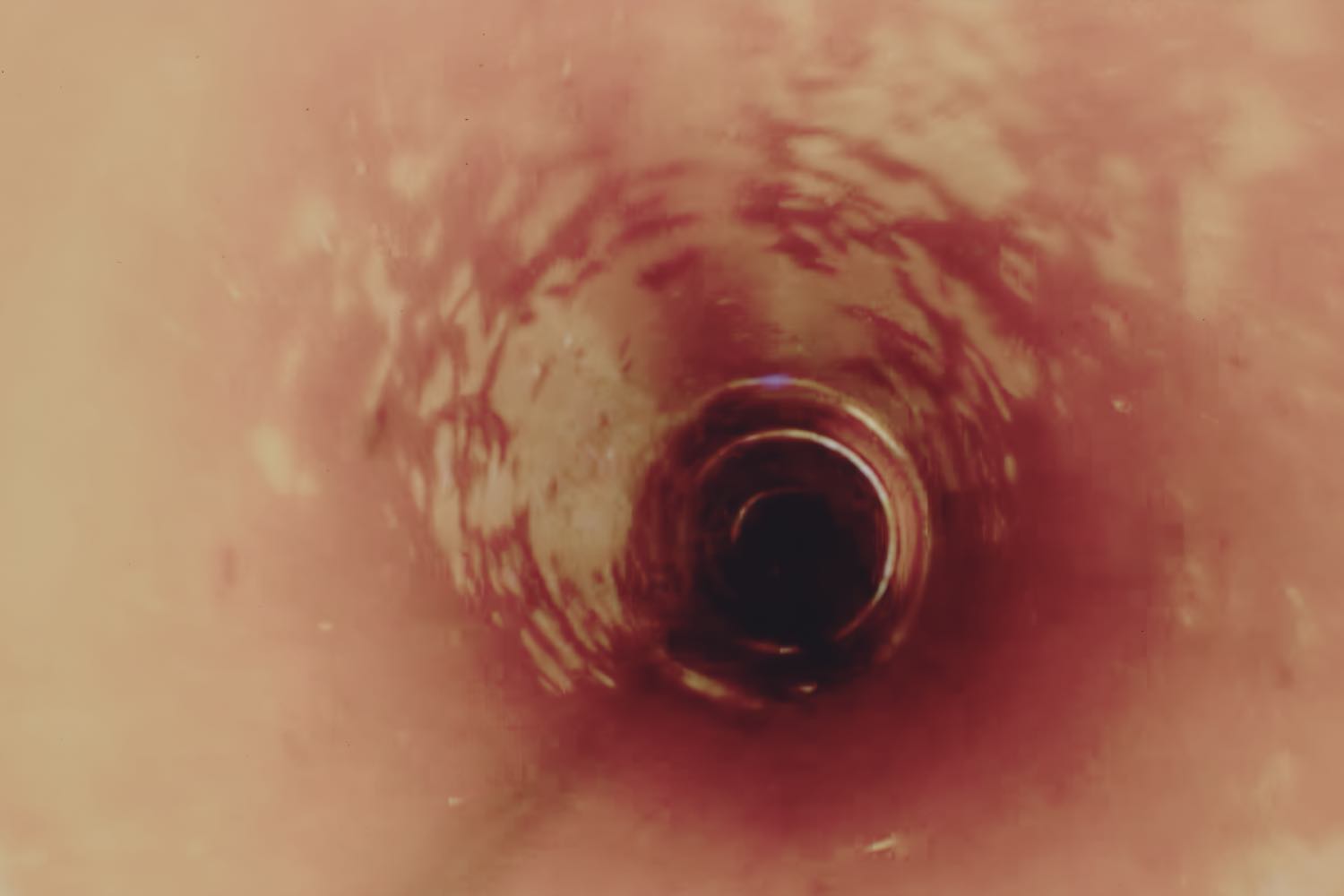

FR: Out of Body does so in remarkable ways, using camera movements that seem to emerge from a symbiosis between human and machine agency, as when the lens penetrates spaces, orifices, and corridors that no person could access while revealing a curiosity and attention that remains profoundly human. Similarly, the camera goes back and forth to “look” at a spider inside a drain pipe. Can you tell us more about the filming and editing process for the work, and the different scenes that it brings together?

LB: I work somewhere between documentary and fiction. When I’m shooting, I try to be open to the constraints that I’m offered by a place. Of course I storyboard. I do research by shadowing people and observing the choreography of a particular process. From there, I think about how to raise questions by embedding a further narrative or playing with the framing that already exists. By playing with the constraints that I’m offered, an interesting tone emerges. In a way, I try to use a deficit as a parameter. I often incorporate technologies and media that I find piggybacking on what’s already in use. Robots, MRI, ultrasounds, and endoscopy are integral infrastructure of these hidden worlds. I like adopting these perspectives to give a particular view that is embedded―one that describes, as you say, the symbiosis between humans and technology. I also love playing with scale and movement, or being on the inside or the outside of a process or an entity. These are things that I come back to again and again.

FR: In the case of Out of Body, what exactly were the constraints that you encountered?

LB: We experienced constraints in what we were allowed to show, whether for regulatory reasons or because the sites of waste management we were shooting in are regarded as contentious and divisive. In each context, we had to consider the time frames we were given, how fast people worked, the time of day, and the information I was able to access prior about lighting conditions, scale, and proximity; these factors determined how improvisational I was able to be on location. As an example, we were shooting in a subterraneous lab in a decommissioned salt mine that holds radioactive and industrial waste. Scientists are developing materials that creep into and seal cracks in the now fragile mine to prevent groundwater infiltration and potential leakage. In their own words, the scientists aim to make these cavities watertight for “eternity.” We had to carry oxygen tanks which were really heavy, and so our equipment had to be nimble and fit through the miners’ turnstiles. We mounted our cameras on the lift that took us four hundred meters underground and on vehicles that snaked us through the mine’s tunnels. As I was moving through this experience, I was thinking about the edit, and adjusted my plan as I went. There is almost no reverberation in those caverns, so as I was observing, I knew I wanted to omit atmospheric sound in my edit. I wanted to embody this experience of going to what felt like the end of the earth.

FR: In your films, eerie melodies are combined with noises from machines, infrastructure, and operations. Voice-overs are never only “voices,” as the relationship between what is said, how it is said, and those speaking (who often appear on screen, as in Out of Body or Notes on Warm Decembers) is also fundamental. How is this attention to sound transposed to how you conceive exhibitions?

LB: Quite often, I work outwardly from a sonic idea. I like directors who do this, like Lucrecia Martel. She thinks conceptually about sound, on or off screen, sometimes privileging sound design over image. This mine is a good example of that. Once I knew I would play with this idea of dead atmospheric sound, I had a shape for the edit. A big part of my process is then working with my composer. For the last few films, I’ve been collaborating with Ville Haimala, who is one half of the electronic duo Amnesia Scanner. Ville is a wizard. I’ll have an idea for how a musical element might have a particular characteristic, and then his score will push it even further to somewhere I haven’t anticipated. Ville is also very interested in mixing digital and analogue approaches so that it’s often hard to know what has produced a sonic effect or melody.

I see exhibition-making as an opportunity to push my sound design even further. Recently, for the show “Out of Body” (2024) at Between Bridges in Berlin, I worked with separating aspects of the sound into different spaces of the gallery. I wanted to give this sense of the soundtrack leaking out, but also a kind of fragmentation in which parts of the soundscape were siphoned off. (In this case, a series of poems voiced by Logan February). I like the idea of encountering something as a fragment, and then later, as part of the whole. Similarly, for my exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, I also orchestrated a spatial soundscape. As a viewer, you could stand between three separate films and have a threshold experience, or you were able to engage with the films autonomously. Intuitively, the installation mirrored the way the projects intersect, but also how materials and bodies in my films emerge through their relationships with other entities. I’ll mix the sound in the space so I can place the viewer both inside the work and inside my experience of making the work happen, which involves a practical and experimental approach to research, I guess.

FR: Your work dialogues with various traditions of knowledge, and you often involve scientists, biologists, or historians of science. How do these collaborations unfold?

LB: Collaboration is at the core of what I do. I don’t want to make things that I can predict from the beginning of the process. Instead, the aim is that something totally new emerges through the relationships I form in doing this work. Depending on whether I’m collaborating with poets, scientists, 3D artists, historians, sound artists, performers, or other filmmakers, each new relationship involves building a method. I’m currently collaborating on an exciting new project with musician Lyra Pramuk that involves scientists and conservationists who are remediating waterways. I am also working on an experiment involving film and performance with artist James Richards, which we will show as part of the closing program he’s putting together in March for Mire Lee’s commission at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. We’ve established a really interesting way of sharing our archives and shaping something together. I feel that with every new collaboration, I learn something about what’s important to me and my own approach, but there’s also something key about not being overly precious and staying committed and open to change.