“Essentially, there are only two things in my life: spiritual practice and work,” LuYang tells me with the help of ChatGPT. Based in Tokyo and Shanghai, the artist prefers to communicate in Chinese and respond to questions with AI translation services. But before writing back and forth, we connect over Zoom. They are in the countryside outside Tokyo, a blanket draped loosely around their shoulders, the sky outside fading from day to night, a beautiful hazy shade of darkened blue. Having just returned from Paris for the installation and debut of their latest film, DOKU The Flow (2024) at Fondation Louis Vuitton, they explain they need to “empty their brain before starting something new.” As a practicing Buddhist and artist who has been quoted numerous times saying they “live on the internet,” this is not simply a euphemism for someone who spends their time browsing the web, playing videogames, or existing only through an avatar: “Mainly, I don’t really like socializing,” LuYang explains when I later bring up this recurrent quote. “I prefer to stay at home and create.”

A few days later, this sentiment resonates as I contemplate bailing on a gallery dinner because, well, I, too, don’t always enjoy socializing. The week prior, instead of going to the opening week of the Venice Biennale, I chose to sit on my couch in Berlin. I zoomed with LuYang and worked through the artist’s extensive archive on Vimeo, where almost all of their works are available to watch for free and at the viewer’s leisure — a welcome change from sitting (or even standing) in what are often uncomfortable exhibition spaces for hours on end, and an important choice that gives viewers without access to such spaces the ability to still experience the work. I also, admittedly, fell into multiple doomscrolls on Instagram, but rather than feeling FOMO from a feed of frenzied proof-I’m-in-Venice posts, I experienced an oddly calming sensation of seeing things without having to deal with the nonstop stimulation of physically being there, echoed by a phrase LuYang once wrote in an online journal: “It doesn’t seem to matter whether we are experiencing everything firsthand, or if it’s just our virtual replica existing and experiencing life on our behalf.”

LuYang’s creative output is deeply rooted in and intertwined with their spiritual practice. Since 2015, the artist has been formally engaged in the Buddhist academy system (though their grandmother was also a practitioner and they were exposed to its teachings from an early age), and with each new work, these two sides of their life become more deeply entangled. DOKU The Flow follows DOKU The Self (2022), both long-form narrative films centered around the artist’s genderless humanoid avatar, Doku, whose face is modeled on LuYang’s own, as they navigate digitally crafted, otherworldly landscapes. The titles refer, in nutshells, to the central themes (the pseudo-notion of the “self”; the self and the universe at large as ever-flowing, liquid concepts), while the avatar’s name is short for the Japanese phrase Dokusho Dokushi. Translated to English as “we are born alone, we die alone,” the phrase stems from the infinite life sutra, a Buddhist scripture highlighting the solitary nature of life. Although we might interact and intersect with others throughout our lives, the beginning and end are inherently individual.

I first encountered Doku’s wild world at PalaisPopulaire in Berlin when the artist had a sprawling solo exhibition, “DOKU Experience Center,” in 2022 on the occasion of receiving the Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year prize. Six LCD screens, organized around a concrete column like a mandala, showed Doku in six different skins, dancing and presenting themself as if a vibrant cast of characters to choose from in a videogame. In contrast, a large projection screen hosted The Self. Elsewhere, visitors interacted with DOKU the Destroyer (2021), a videogame in which users guide a gigantic monster version of Doku in an effort to destroy a city. (Uncannily, the game is based on a live motion-capture performance that was staged in Moscow and streamed worldwide shortly before Russia invaded Ukraine, a fact the artist personally feels “was somewhat like a coincidental prophecy.”) In The Self, Doku cycles through assuming the six vivid personas also shown on the LCD screens, each of which is based on one of the six Buddhist realms of saṃsāra, or rebirth: heaven, asura, human, animal, hungry ghost, and hell. The artist explains that the concept of these six realms — also explored in the videogame The Great Adventure of Material World (2020) — “is not merely a superficial description of the possible states of life and suffering one might experience through countless rebirths. It also carries deeper symbolic meanings: each realm represents specific emotions, life conditions, and psychological traits.” The audience watches as Doku experiences ecstasy and joy, suffering and death, with the surrounding virtual landscapes and the accompanying soundscapes — composed by the musician liiii — morphing to underline the qualities of these different states.

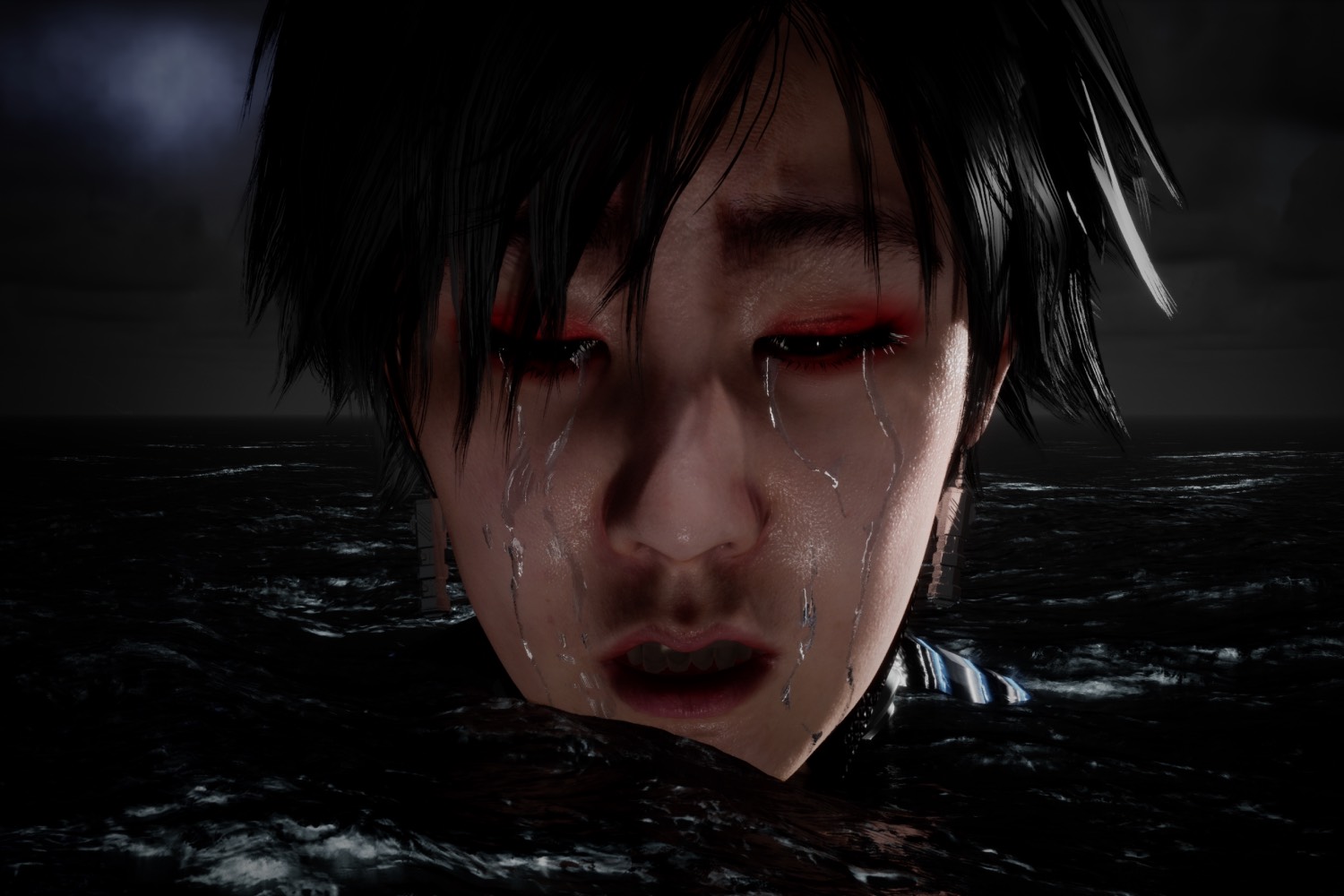

Building from The Self, in The Flow Doku boards the Desire, a cruise ship designed to satisfy the five great desires of all beings: hunger, wealth, sleep, fame, and sex (or, in the film, sensuality). Slipping again between the six different skins, Doku becomes entrapped within the game of life, attempting to alleviate pain and suffering through external validations and by placing their faith in the illusions of the material world. Eventually, the cruise ship sinks, backdropped by the narration that “all desires are like seawater; the more you drink, the thirstier you become.” Though other figures appear intermittently, a wrinkled, gray-haired Doku eventually struggles to cross a rocky terrain; surrounded by darkened static figures, the avatar is, ultimately, solitary. In Buddhist teachings, the path to true liberation is a journey one must complete alone.

In my exchange with LuYang, it becomes apparent that the saga presented in the DOKU films, which will continue to be developed (part three, they say, is titled DOKU The Illusion and will premiere later this year), likely functions as a visual and aural manifestation of a meditation technique in which one contemplates the suffering in saṃsāra: “This method involves imagining oneself experiencing the true suffering of each realm,” LuYang explains, “not only the pain of hell but also the suffering in heaven, eventually developing a renunciation of all these attachments. Many religions aim for heaven as the ultimate goal, whereas Buddhism’s ultimate goal is to escape all cyclic existence — including not even desiring heaven — because any attachment to pleasure still causes suffering.”

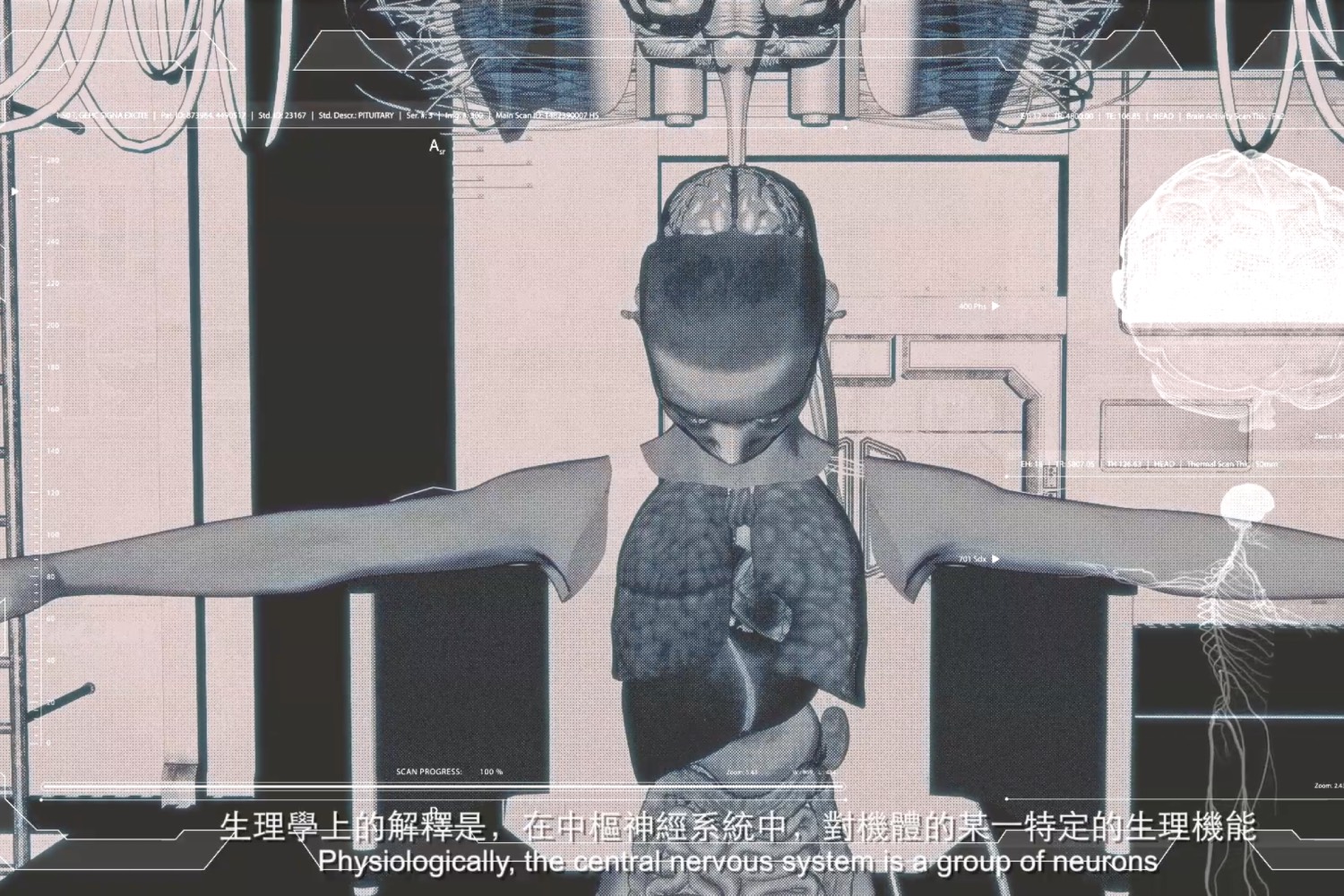

As felt in the DOKU works, the question of human existence — how we inhabit or even define a body and our life experiences — is central to LuYang’s entire practice. Earlier works like LuYang Delusional Mandala (2015) show the artist creating a 3D scan of themself and their avatar’s subsequent birth, life, and death, diving deep into the functions of brain nerves, sensory perceptions, and consciousness along the way. Building on this are LuYang’s Delusional Crime and Punishment (2016) and Delusional World (2020), the notions of the world and the self becoming blurrier and blurrier — a concept associated with the Buddhist doctrine of anattā, or the “non-self.” This idea, the artist says, “suggests that individuals should see through and transcend their attachment to the ‘self,’ realizing that the ‘self’ is a temporary and ever-changing construct, not a fixed or permanent entity.” Such an understanding helps reduce egocentric thoughts and behaviors, leading to more compassion for others.

The opening minutes of The Self show Doku waking up from a dream in a seat on an airplane flying through heavy turbulence — a setting inspired by LuYang’s own turbulent, near-crash experience on a flight during the pandemic. Though there are other passengers, Doku appears alone, the other people flailing about yet silenced, everyone concerned for their individual well-being. Soon, the other passengers and the plane itself disappear, and Doku, still in their seat, floats amid the universe. Also remembering the wrinkled Doku at the end of The Flow, I think about how, even if we are surrounded by others, a certain emptiness arises when we act too independently or are too focused on our individual selves. We find ourselves traversing life in search of the realm that seduces us most, consciously or not, becoming optimists, sadists, humanists, masochists in the process; in turn, we lose sight of truly meaningful, symbiotic connections to each other, to the world, and to others around us.

This complex, perhaps seemingly subverted concept of emptiness reverberates within two Buddhist texts LuYang has been known to cite: the diamond (vajra) and heart sutras. “I am not capable of fully interpreting the transcendent wisdom of these two classics,” LuYang says when I bring them up, but indeed, “both texts deeply explore the Buddhist concept of ‘emptiness,’ which posits that all phenomena lack inherent self-nature and arise dependent on other factors, with no independent existence. These two scriptures reveal the mutable essence of the world by highlighting the interdependence of material and spiritual phenomena, thus encouraging us not to cling to anything,” including the self. LuYang also references these sutras concretely in multiple works. When playing The Great Adventure of Material World, gamers are instructed to search for the “ultimate weapon”: the vajra. When Doku’s body, brain, and entire nervous system shatter into crystalline parts towards the end of The Self, LuYang is referencing both the diamond and heart sutra. Moreover, by depicting the destruction of the earth and bodies inhabiting it, the ending also invites the medicine Buddha mantra, a prayer for the elimination of the pain of true suffering, for the healing of a world plagued by traumas like pandemics and wars. Extending this vein of thought, The Flow opens with the diamond-like splinters of Doku being pieced back together, while the finale concerns bardo, an intermediate state between life and death; in the film, a bardo prayer — chanted by Pema Tashi Rinpoche from Dzogchen Monastery and the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism — is offered, LuYang says, “for the protection for beings who have died, are dying, and will die due to conflicts in this world, and to wish them freedom from all fears.”

One afternoon, when I attempt to let go of the concept of time and fully submerge myself in the countless hours of video material on LuYang’s Vimeo channel, the anime- and videogame-inspired visuals, poetic texts, and philosophical and scientific references bleed from one video into the next. Each work informs those to come while drawing inspiration from those that came before. I jot down lines of text (in their videos, the narration is recited in Chinese with English subtitles) like “life and death happen simultaneously,” “it is my stubborn mind that controls me, not the physical beings I am fixed upon,” “do not think of death from the perspective of life,” and “break free from the mind trap formed by binary concepts.” “Although the mind is intangible and invisible,” the artist later tells me, “all human actions begin with the mind and thoughts. Simply put, if everyone can [learn to] control their own mind, we can gradually make the world a better place.”

The week after Venice is Berlin Gallery Weekend. During the preview days, I venture from the safety of my couch to a few galleries, including Société, who represents LuYang. In the gallery’s office hangs the artist’s DOKU – Animal – Bardo #3 (2023), a circular inkjet print on aluminum showing Doku in the animal realm, surrounded by species ranging from zebras to rats to fish to frogs. While a neon light emanates from around the edges like a halo, the shape and organization of the mandala itself correspond to that of a traditional bhavacakra, or wheel of life, a visual teaching aid representing the six realms of saṃsāra often found on the outside walls of Tibetan Buddhist temples and monasteries to help non-Buddhists understand Buddhist teachings. Standing here, it is evident that no matter the context in which LuYang’s work is experienced or the medium in which it is rendered, what the artist has expressed to me rings true: “All of my works are interconnected; they cannot be viewed as absolutely separate, independent entities,” they say. “I am a stream of consciousness.”