My father recently told me how he often walks around the house opening doors and gazing into empty rooms. He stands there at the threshold, looking inside, taking it all in: the arrangement of the furniture, the way the light falls on the floorboards depending on the time of day, the silence. I wonder what exactly he might be looking for. Is he simply surveying the space, soaking it all in, or is this really about memories, imaginings: the way things used to look, the different people who have moved through a room (talked, laughed, listed, cried), how things might have looked today or tomorrow, if life were different. In other words, how many possibilities is he seeing at once, amid this silence?

Speaking with the Zürich-based artist Louisa Gagliardi about her large-scale painting for the 2022 edition of Art Basel Unlimited reminded me of my dad’s preoccupation. She describes the work in reference to an atmosphere of “opening random doors and observing whatever scenes hide behind them. That’s what I want the work to feel like. Sometimes you open a door to an empty room that has a peaceful stillness, but it’s still eerie because of the potential for activation. On another occasion, a door might open into a situation where something has just happened and you can feel the heaviness of an aftermath.” Gagliardi conjures these moody moments with vignettes that have a marked flatness but also a multitude of registers (layers, even): of imagery, perspective, and time. Melded together, these resonate with a certain sweet melancholy of days gone by, or of lucid dreaming.

Despite this characteristic flatness, at eleven meters wide, Gagliardi’s work for Unlimited, Tête-à-Tête (2022), is a painting that creates a space one could imagine stepping into, given its cinematic scale. That and the fact that it depicts a scene not so far removed from the feasting that accompanies art fairs like Art Basel or grandiose art-world events like the recent opening of the 59th Venice Biennale. Anyone who’s anyone, taking a seat at the table. Gagliardi’s table is a huge circular slab at which two people sit — though completely disconnected — amid the debris of decadence: there are plates piled high, shiny cherries scattered everywhere, a half-eaten cake oozing cream, bottles toppled over, smashed glasses and sharp fragments. Imbued with an unambiguous air of loneliness, the person to the right, who wears a crushed-silk purple suit, stares out at the viewer glassy-eyed; the person to the left, dressed in fur, is slumped over and weary, an imprint of their made-up face transferred onto the tablecloth, pink eye shadow and peach lips a smeared reflection that they’re almost slurping up. Hungry narcissus.

There’s a certain “Bat for Lashes-ness” about the work, conjuring her song “Laura” and just what’s left when the (art) party dies: When your smile is so wide and your heels are so high / You can’t cry / Get your glad rags on and let’s sing along / To that lonely song. Gagliardi’s world expresses the sense of dissatisfaction or unhappiness that bubbles beneath the hubbub of art-world grandeur, and while stopping short of a moralizing tone, it hums with melancholic solitude.

Having trained in graphic design in Lausanne, Gagliardi first began exhibiting her paintings in 2012. She draws upon this training by combining digital-imaging processes with more physical, gestural interventions. Beginning by sketching an idea using pen or pencil on paper, she then scans this onto the computer and manipulates it in Photoshop with a trackpad, tablet, or mouse. She says, “Using a trackpad is similar to finger painting: touch is right at the fingertips, with a lack of detailed control. Using a stylus or tablet is akin to pencil and paper: quite a lot of control in a mimicked manner. A mouse is more like seeing Matisse utilize a stick — it offers control and detail at the tip, alongside a particular fluidity.” Shifting from the immediacy of the physical gesture with her sketches, the computer then provides a “distance,” a push and pull between the intimacy of touch and the detachment of the screen. Gagliardi completes her works by printing them on glossy PVC material and making interventions with milky wet gel medium combined with ink or nail polish, echoing the luminosity of the computer display, smeared or slicked with lustrous oily brightness. As such, the artist reacts to our Web 2.0 surroundings, moving between the analog and the digital with a fluidity and ease that resonates with our everyday modes of looking and, moreover, being: screen, world, screen, world.

A theme consistent throughout most of Gagliardi’s paintings is her interest in depicting the body with undertones of existential discontent. Indeed, this is what roots her work in the uncanny or even dystopian. Bodies are often rendered as all-purpose viscid repetitions: humanoids or androids that aren’t quite one thing or another, situated in flat realities or spaces at the edge of fantasy and dreaming.

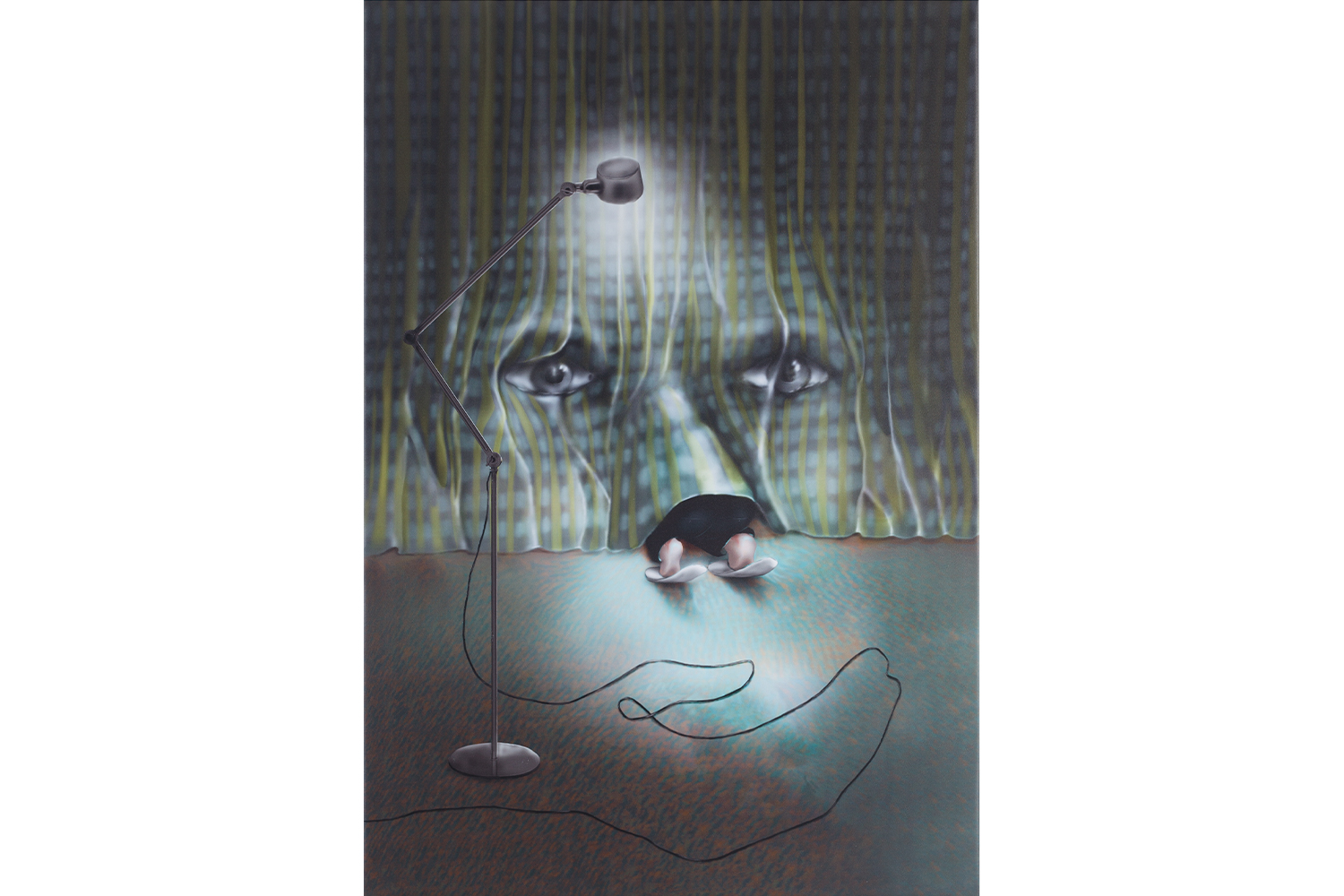

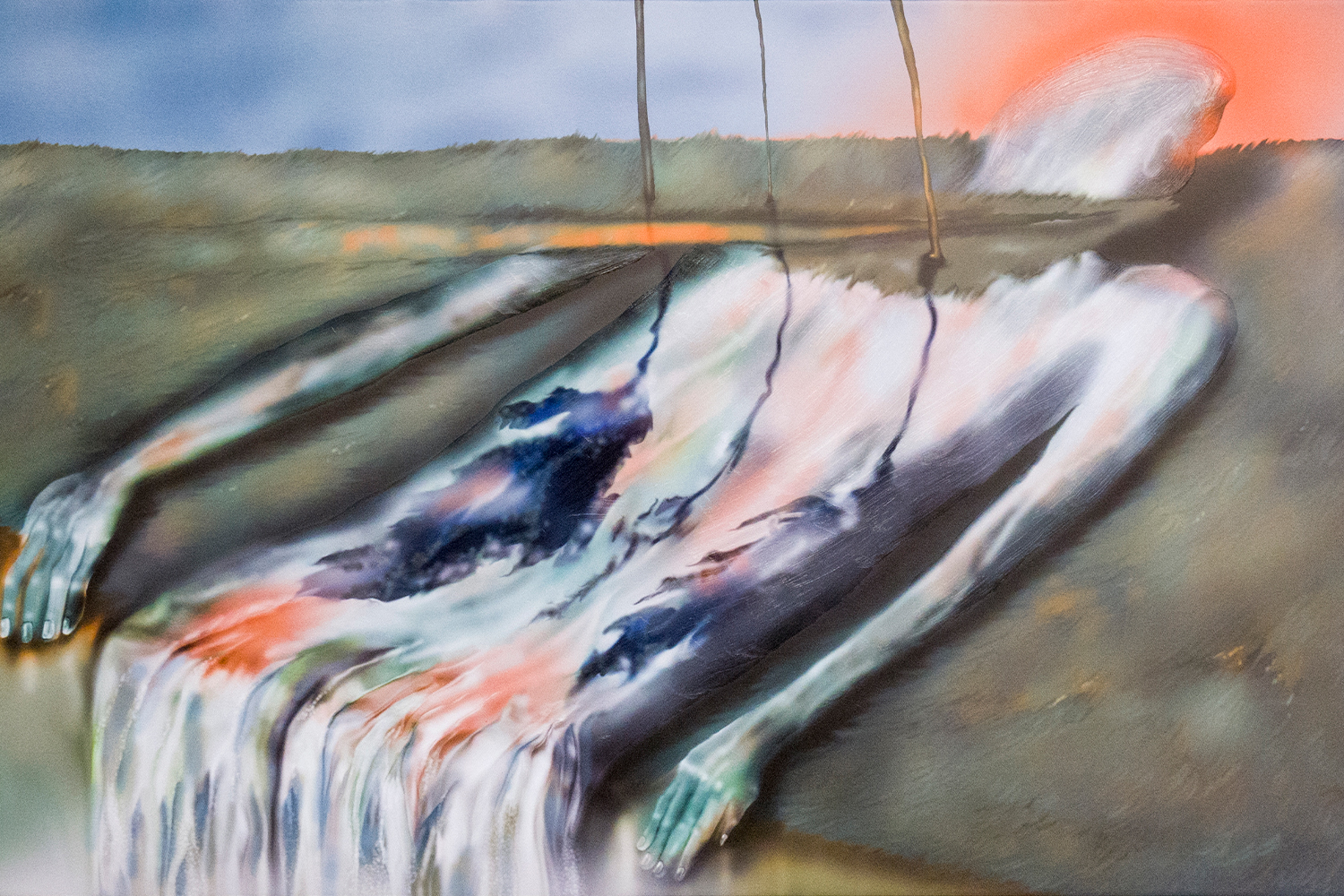

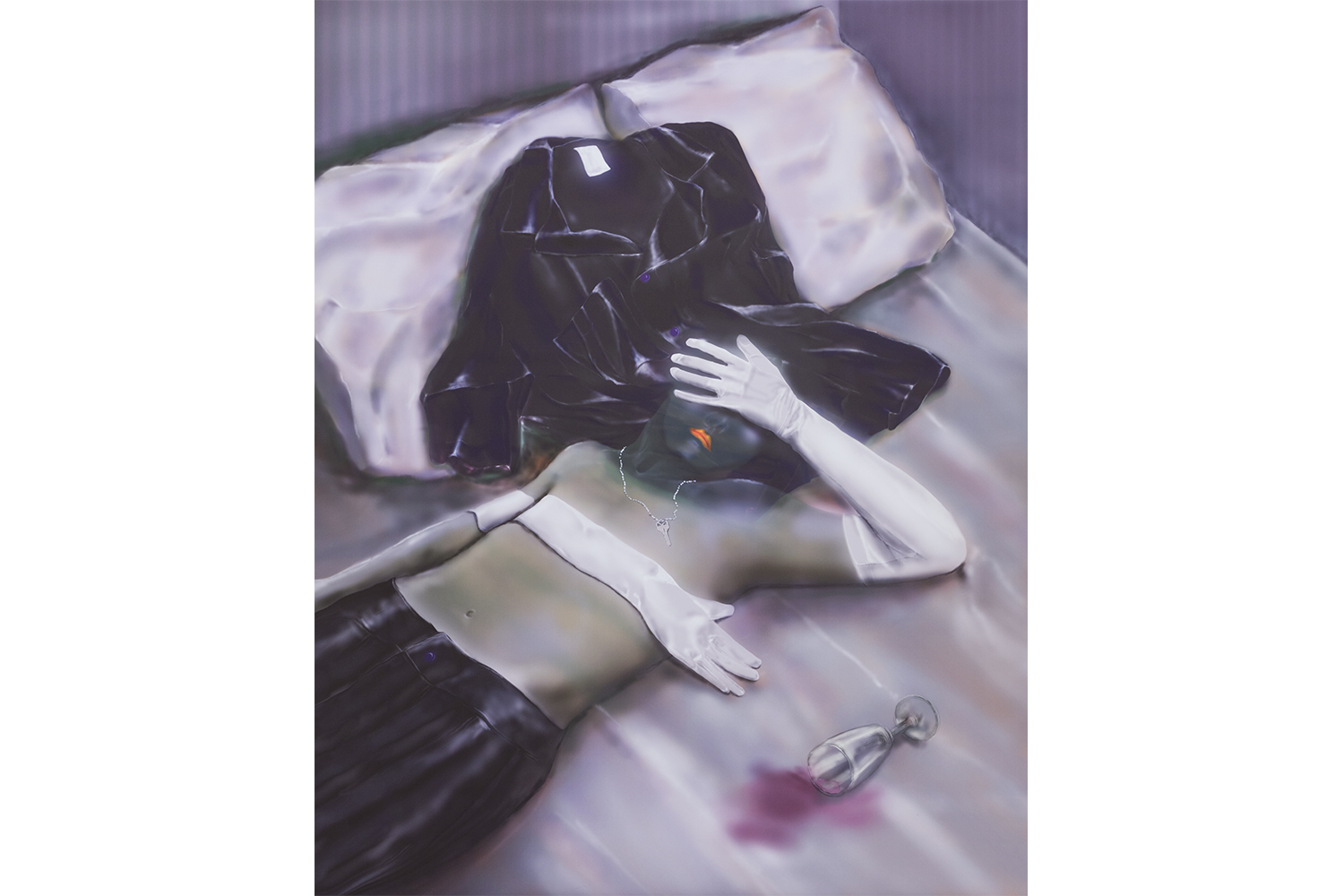

Earlier works from 2015–16 often use close-up framing, so that luminous flesh fills the image or is surrounded by darkness. Take, for example, Untitled 2 (2015), in which forearms could be thighs, fingernails could be nipples or eyes, limbs and body parts interlacing and interchangeable in an orgy of skin; or there’s Untitled 1 (2015), in which a floating hand ominously casts a monstrous shadow onto someone’s naked back, their shoulder blades and buttocks incandescent with Caravaggiesque light by nightfall. A few years later, in 2018, Gagliardi’s bodies actually become landscapes, melting or seamlessly integrating into the surround, blurring the line between figure and ground. In Purgatoire Pastel (2018), a giant man is shackled to a building by a road that binds his wrists, while in Morning Glory (2018) a person liquefies, doubling as a pool that reflects grass and trees, eventually cascading into a waterfall. In Curtain Call (2020), figure-ground perception shifts into illusion, as a person crouching under a curtain hides from a spotlight doubling as a smiling face. Gagliardi’s bodies speak to an inexplicable corporeal entrapment: the sense that self-determination is, in fact, a myth of our own making. A case in point is Another Avalanche (2020), which sees a person sitting at the end of a bed, window frame casting ominous shadows like prison bars, a spilled drink forming mercurial rivulets: the bed as its own penitentiary of isolation.

Even when Gagliardi’s forms do attempt escape into sculptural form they struggle with wholeness and completion. Her exhibition at the Swiss Art Awards in 2021 saw figures realized in three-dimensions: a person lying on a rug surrounded by candles and with chains extending and tethering two dogs. However, these forms remained entirely flat, paintings essentially cut out and arranged in space, as if flattened by a steamroller. The huge metal spoons at her 2020 show “Wishful Thinking” at Antenna Space in Shanghai did the same: occupying space by leaning up against columns or spread across the floor, but without any inklings of depth or volume. And when her sculptures do have depth, they are made of transparent mesh: bags, gloves, hats, glasses, and tables with an elusive lightness of being. These ghostly apparitions are seemingly deficient and weightless, flaccidly wilting under the pressure of their own existence, as in her 2018 exhibition “On a Day Like This” at Plymouth Rock in Zürich.

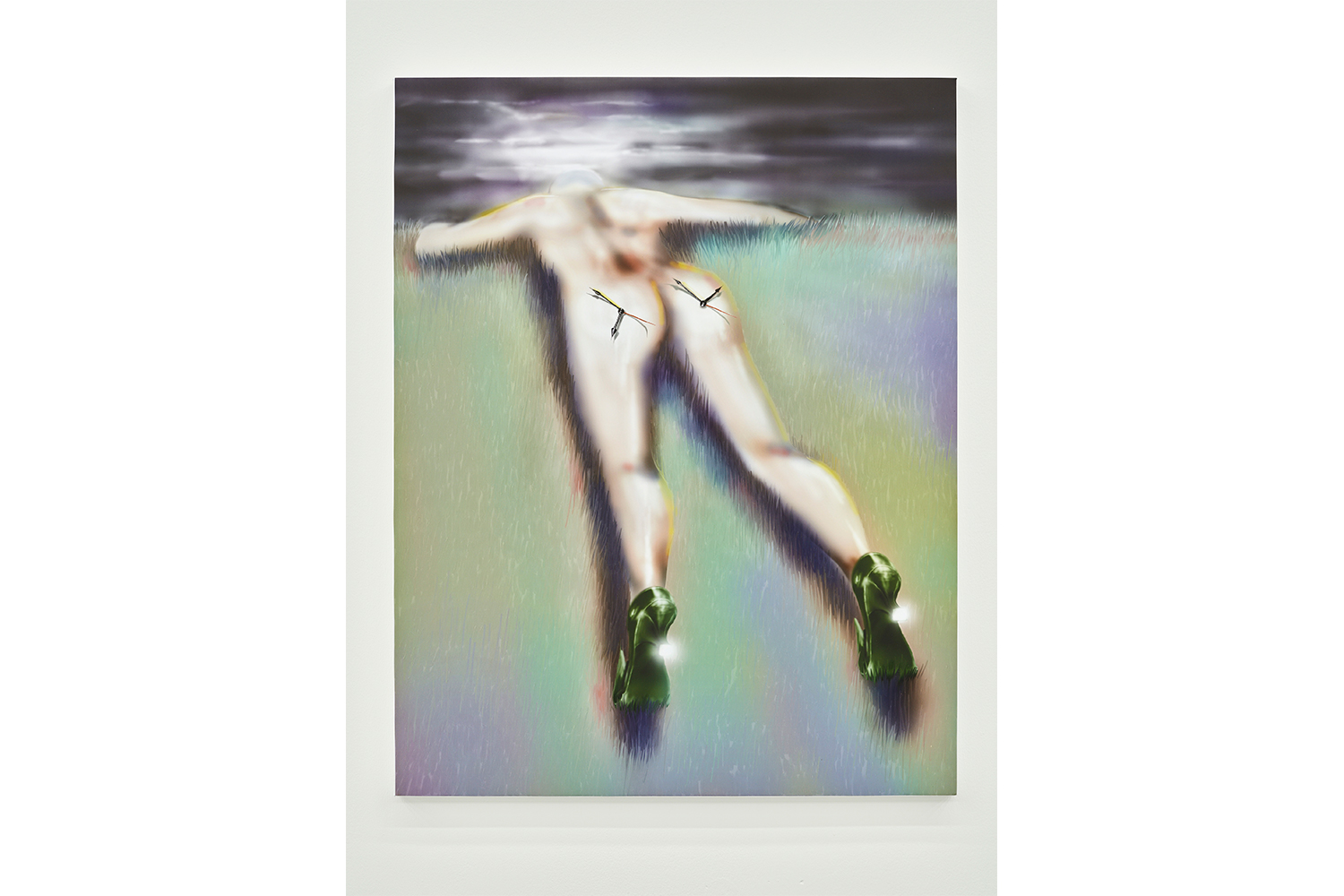

In this sense, Gagliardi’s work posits a kind of flattened reality, one that levels society and suspends time as we know it. Fittingly, images of clocks or watches are a recurrent theme throughout her oeuvre. Take, for example, Two Timing (2020), in which a naked person’s buttocks are ticking with the hands of time, the right cheek set to just before two o’clock and the left to seven o’clock. Indeed, the stopwatch in Inundation (2020) sits buried at the bottom of a fish tank, telling — oddly — exactly the same time: just before two o’clock. The register of time in Gagliardi’s work is more like that of a dream sequence, reality shaken by little moments of oddity, with the experience of linearity rendered irrelevant. There is the suggestion of (embodied) time working differently in another realm — like in a video-game platform, in which time and space can be expanded infinitely, built with its own rules and reasoning.

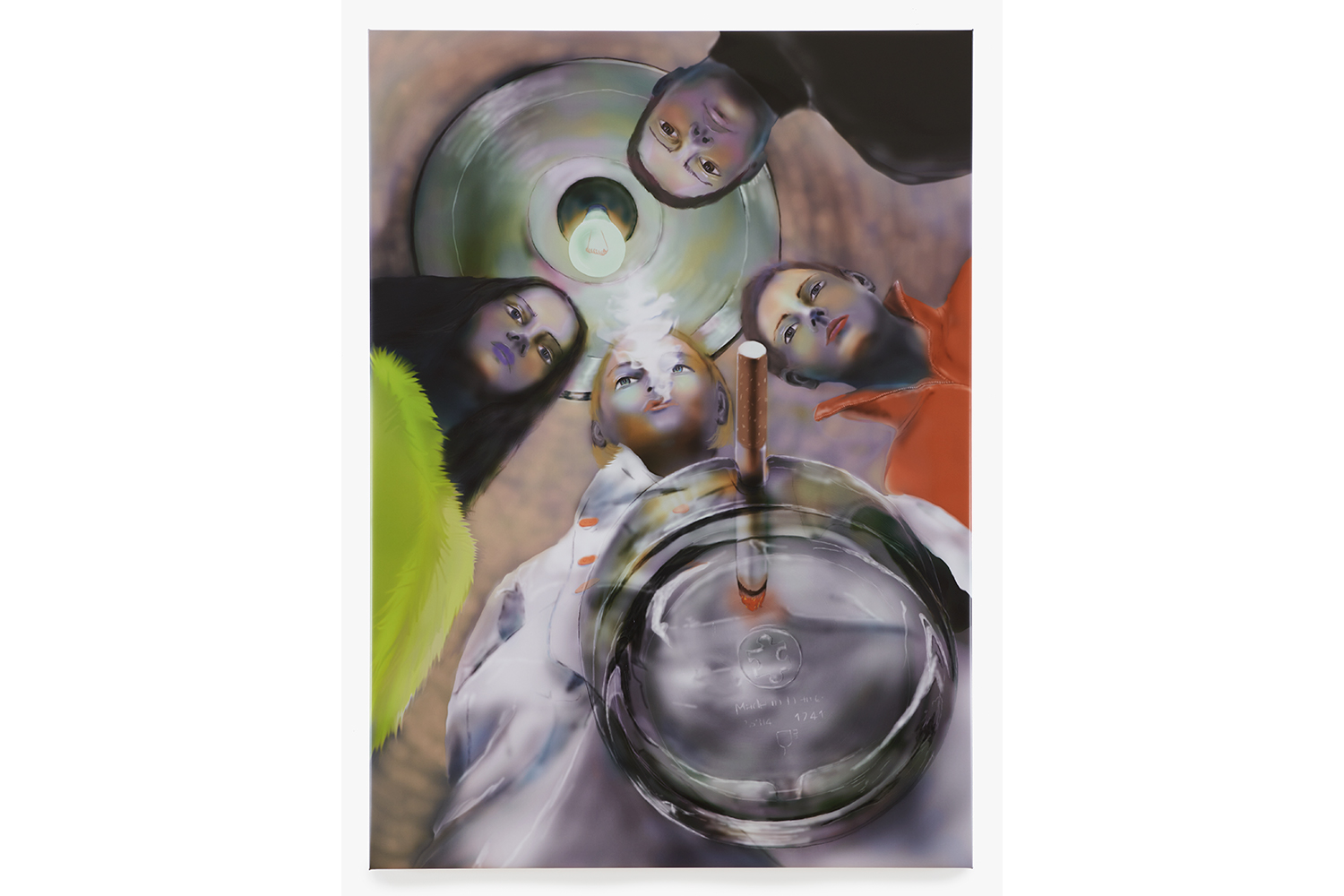

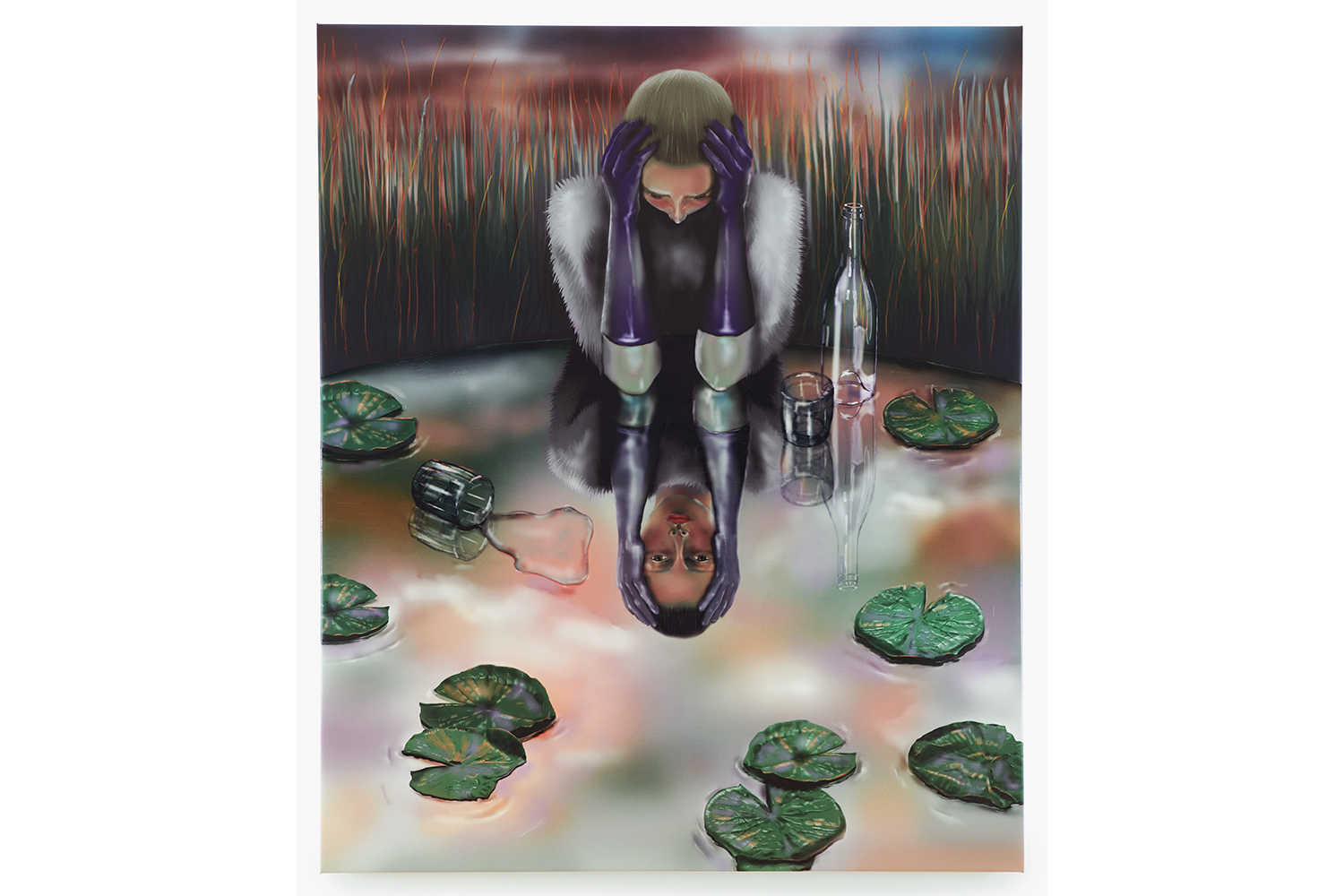

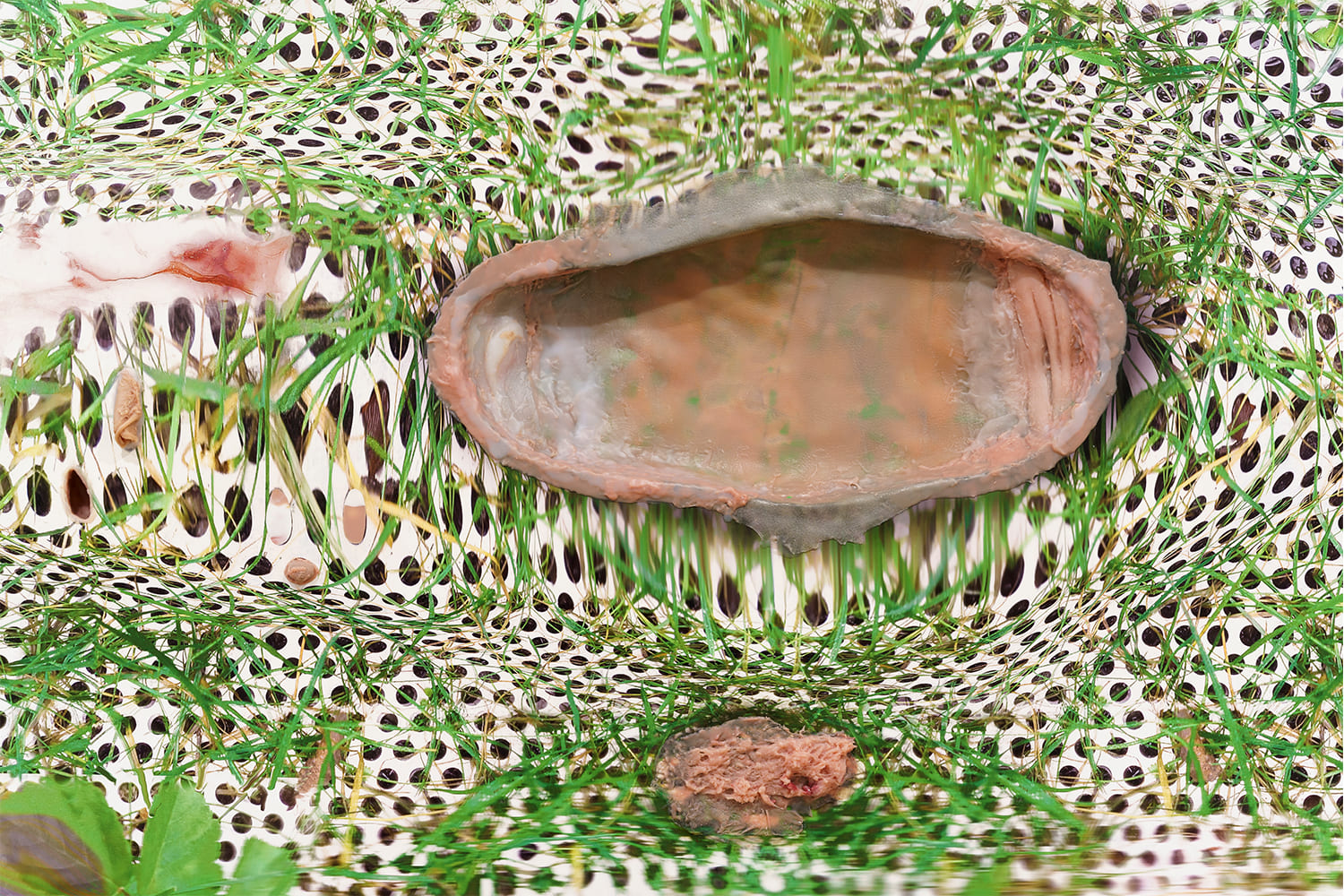

The opposing states of transparency and reflection are also continually returned to in Gagliardi’s paintings. A face is mirrored in a perforated colander (Strained, 2019); a woman wearing shiny purple gloves stares at her own image in a lake filled with lily pads, which simultaneously doubles as a tabletop (Reflection, 2021); a person’s image becomes engorged and monstrous, caught in the gleaming sliver of a cooking pot (Apples and Oranges, 2020). Conversely, other works depict bodies as phantasms that are either coming into being or disappearing altogether — Steaming (2019), for example, shows a white silhouette holding an iron, an immaterial face puffing out of the metal plate as plumes of steam. These are like afterimages, pictures that tick around an overstimulated imagination, or memories that float into your brain, and which might come back as dreams or fantasies — or as you stand on the thresholds of doorways, looking into silent, empty rooms.

One of the key focal points of reflection in Tête-à-Tête is the chrome water jug, which sits in the bottom right-hand corner. The viewer’s own image is pulled into this object, shown gazing at Gagliardi’s painting within a white-cube exhibition space. This is the viewer as voyeur, a portrait of our own “navel-gazing and self-absorption,” as Gagliardi puts it.

The eeriness or dreaminess of Tête-à-Tête lies in particular in the anthropomorphic details that reveal themselves the longer you look. Heaps of butter on a piece of bread morph into a figure, legs splayed, parsley as pubis and nipples; the last puddles of champagne and wine double as faces bobbing in boozy remains; a pair of black leather gloves flop over a chair like an oddly flattened hand, deflated. Meanwhile, pale, pearly silhouettes of figures dwell in the background. Translucent and faceless, they begin to merge with the furniture, chairs doubling as bodies with thick gleaming torsos. They are absent placeholders, flesh fading into cotton and air and nothingness, bodies as both form and inanimate objects. There’s a certain solemnness to this proposition, and a sense that the supposed communality and joy of breaking bread together is, in this context, ultimately equivalent to an illusion filled with fading ghosts. Winking at Luis Buñuel’s film The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, a surrealist story about a group of bourgeois friends attempting to dine together, Gagliardi highlights the relentless pursuit of desire and the entitlement inherent to this scenario.

Is this an overt swipe at the undercurrents of hypocrisy, shallowness, and greed that can run through market-oriented events such as Art Basel? A nod to the equivalent waves that crash into Venice every two years? Gagliardi says, “Tête-à-Tête is not so much a critique as it is an expression of the weirdness of large-scale formal events, while playing with the recreational aspect and social anxiety that accompanies such instances. There are elements of leisure and obligation, pleasure and discomfort. It’s an exhausting balancing act that I believe to be relatable to practically anyone who has had the (mis)fortune of experiencing such occasions. Throughout moments like these, there are occurrences that give one different perspectives, and that makes things truly worthwhile on another level.” Yes, many possibilities can unfold in an instant — depending, perhaps, on your level of cynicism, and just how many cherries are already on your cake.