On a clear moonless night, looking out from the shore, the horizon might disappear and the two great physical voids of life on Earth would collapse into one. The stellar sky and the ocean’s seemingly endless waves have been familiar, if hackneyed, mental locales for the poet, the painter, and the philosopher across millennia. The sea and the stars remain surfaces of enlightenment and masses of the unexplored — truly voids in their scale and inhospitality. It makes sense that Liz Larner, an artist who has negotiated space for the past three decades, would find both realms to be of abstract interest. At Kunsthalle Zurich her exhibition “below above” announces as much, continuing a career spanning succinctness in form and language that contains meanings with multiple ends.

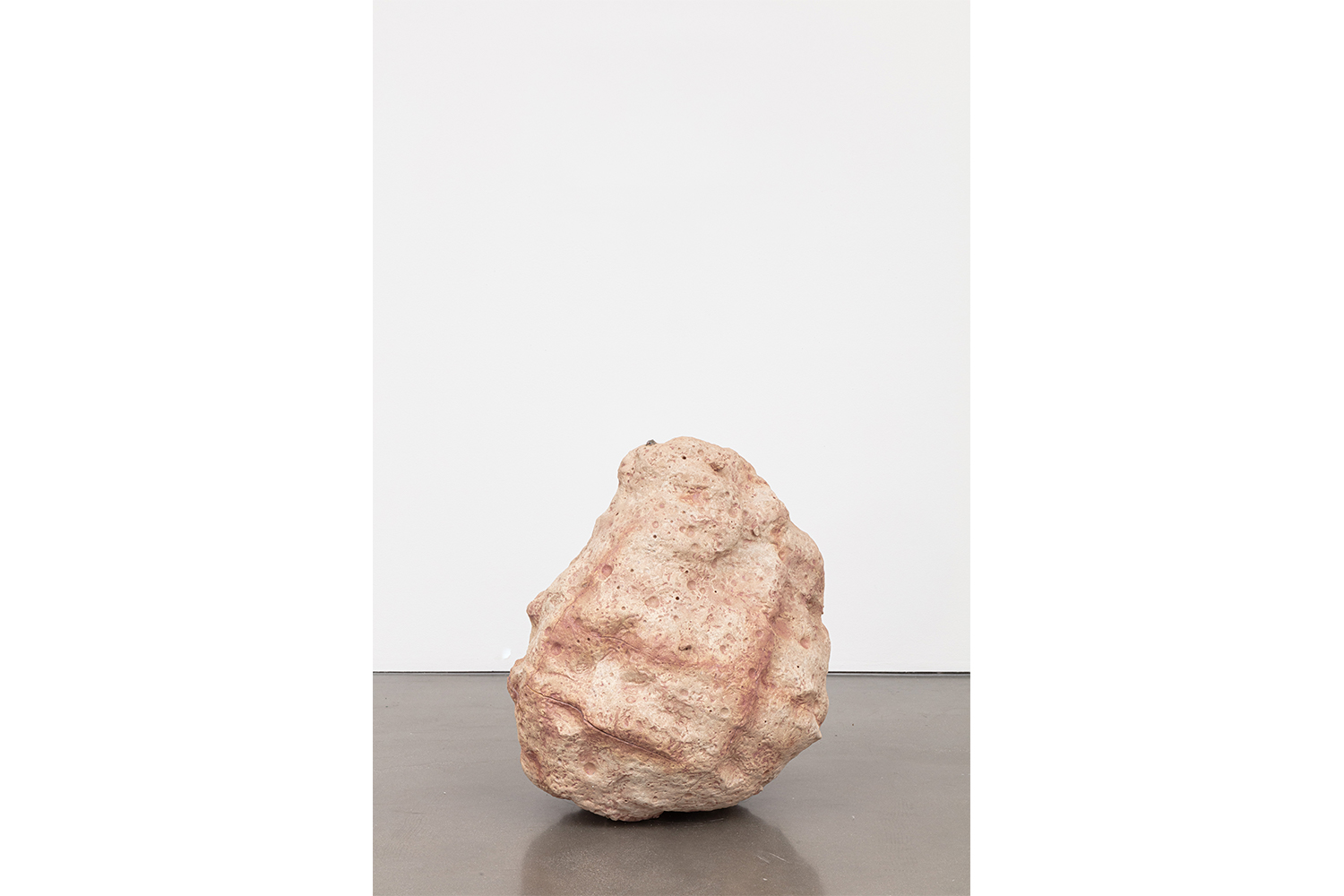

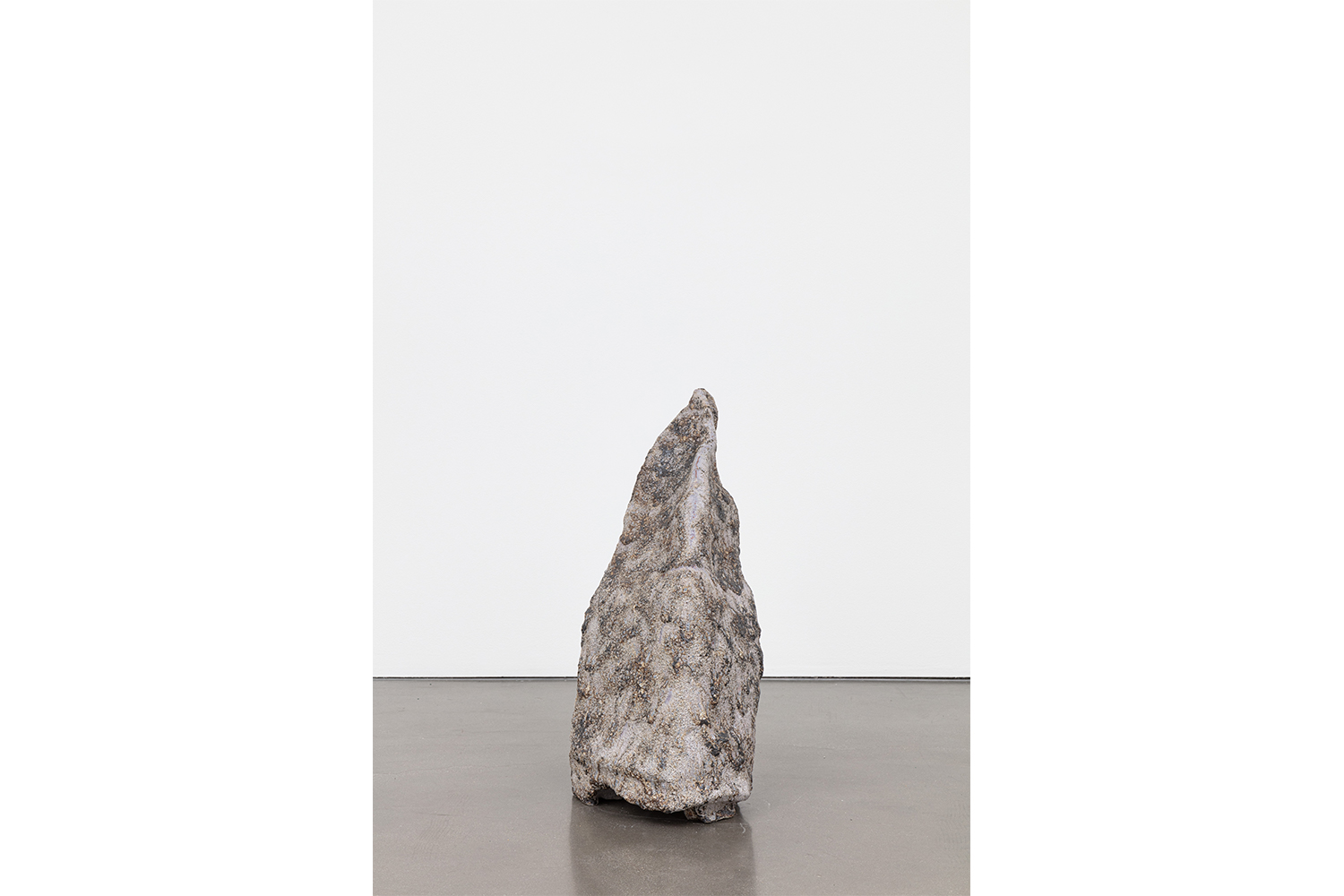

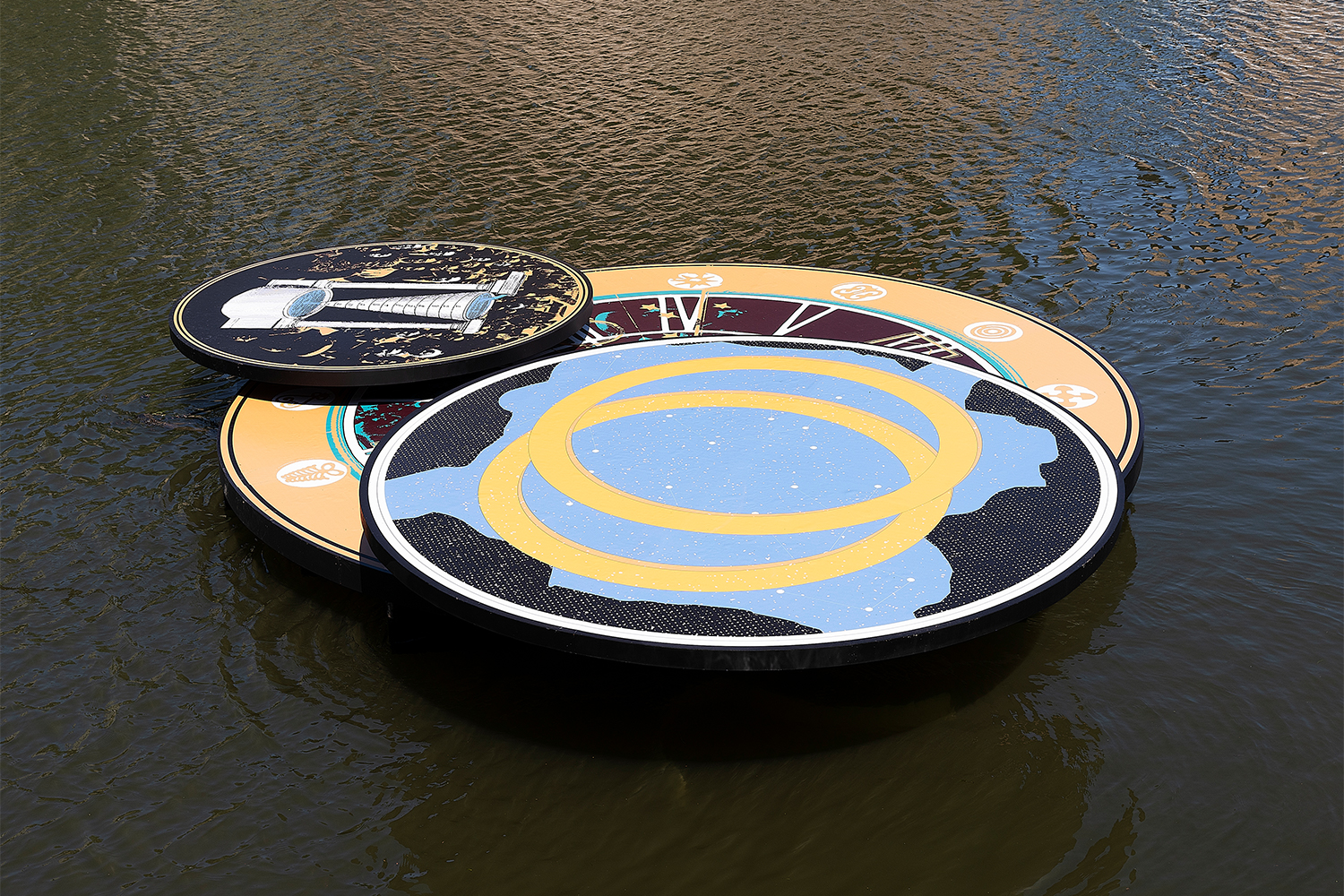

One might imagine the title refers to the spaces of the two floors dedicated to the exhibition in the cavernous Lowenbrau complex. The upper space contains a non-comprehensive four-decade survey of Larner’s practice; the lower features a new low-lying total installation. That work, a pairing of two recent bodies of sculpture, is many things at once, vulgar and graceful chief among them. It relates to the sea and sky in ceramic works titled Asteroids (2020– 22) and masses of acrylic-coated plastic refuse titled Meerschaum Drift (2020–21). The latter, riffing on its namesake, which suggests sea foam, includes bundles of bottles, containers, even plastic Halloween masks, grouped into low snaking curves that recall giant sand ripples on a concrete shore. Their source material is immediately recognizable, and yet the porosity of their compilation and the matte acrylics (plastic on plastic with plastic) applied in soft tones of iridescence reject the transparency and shine we typically associate with this unstoppable human creation and waste. It’s that permeability within the constructed density that is most felt by the viewer, just as meerschaum is also the name of a rocklike material so light it sometimes floats. The flipside of that are the thirteen heavy ceramic sculptures scattered throughout the plastic drifts, asteroids impossibly brought down to earth. Echoing the forms of known celestial bodies as well as imagined ones, they continue Larner’s project of merging abstract form with extant replicated form within a single work. In total, the effect is quite odd for sculpture: the entire sequence of units, each successful on its own as an individual piece, is slightly pushed to one side of the room so that the viewer can neither circle nor view it from a direction not chosen by the artist. It becomes a landscape suggesting both bays of rubbish and stardusted galaxies. There’s a politics of consumption entered within their forms, although an asteroid belt is also a type of litter, soon to be outdone by the unregulated excursions of Elon Musk and the like in the near-Earth atmosphere.

Upstairs, Larner’s ability to complicate structure and meaning is elaborated further. It’s a nice pairing to have the new complemented with an old that doesn’t attempt the exhaustive. Her earliest project, Cultures (1988), stabilized cell cultures of other artists’ breath, suggests a fascination with the constructed impulse in the micro as well as the macro as it relates to both culture and the wider world. A finish-fetish mirrored steel form, X (2013), alternately seems to rise from the floor or set down like a moon lander upon it. In a back corner, a cloud of silver, Hands (1994), reveals itself to be helixes of pewter casts of the titular object hanging from tender silver chains. They’re hollow, like bizarre gloves, and their effect ranges from the lifelike to the uncanny. The weightlessness in their recognizable form is dazzling. It exhibits Larner’s commitment to the exploration of materials, shifting between mediums and motifs, with an understanding that the sculptural always places the human at its center. For what structures are we most apt to understand, whether on heaven or earth, beside those constructed in our own image?