To gaze at a painting from Li Qing’s “Neighbor’s Window” series means to peer at an urban panorama from within a rural interior. The oil painting rests on the glass panels of a wooden window frame. The discarded frame, sourced from the Chinese countryside, is in discord with the painting’s depiction of an early twentieth-century Shanghainese building. If the painting were to convey a simple message, it would be the fantasy of abandoning the receding agricultural countryside and embracing a prosperous urban contemporaneity. Indeed, this is a predominant narrative in present-day China: according to The Economist, approximately 250 million rural migrants have flowed into China’s cities since the turn of the century. Mainly recruited for construction projects, these migrants are building China’s modern metropolises. But for many, the chance of becoming a full citizen of an urban center is limited by the impossibility of obtaining a hokou, a household registration that affords one full access to a city’s social services. A lack of hokou means keeping one foot in the countryside — that is, the unavoidable return to the native place where one is enlisted. The materiality of Li Qing’s paintings seems to touch upon this paradox: China’s rural flight doesn’t always diagrammatically conclude in the metropolis, but rather bounces lives between two poles. Urban modernity, as exemplified not by aerial skyscrapers but the more bodily palazzos, remains for many an ungraspable reality. Like President Xi Jinping’s alleged “Chinese Dream,” it is “in the vicinity” — to mention the title of the artist’s first presentation of the series — but it is still a detached “outside.”

The iconography of “Neighbor’s Window” translates an ongoing cultural debate concerning tradition and China’s achievement of modernity through “Westernization” into a dialectic of insides and outsides. The subject of the series is a diversified collection of buildings in Shanghai and other Chinese cities that share a similar colonial past. Among those in Shanghai, a few of them stand on the Bund, the iconic western waterfront of the Huangpu River: they are hotels, flagship stores, headquarters of international corporations, banks, and newspaper offices — in any case, complex conjugations of the many architectural mannerisms that originated in Art Deco. Their referentiality points to modern Shanghai’s quintessential permeability of international aesthetic styles. Other buildings depicted in the series show the appropriation of codes of Stalinist architecture, the result of political affiliations between the Communist Russian and Chinese governments. Paintings such as Neighbor’s Window: Casino (2014), depicting the Casino Lisboa in Macao, and Neighbor’s Window: Moscow Style (2013) or Neighbor’s Window: St. Petersburg Style (2013), both displaying the Shanghai Exhibition Center, formerly the Sino-Soviet Friendship Building, evidently present the series as an exploration of twentieth-century foreign architecture in China. However, if Casino recounts the period in which the openness of colonial cities was dictated by a truly cosmopolitan ethos — and indeed, the appropriating gestures were genuine, diversified, and countless — Moscow Style and St. Petersburg Style evidence the later embrace of a foreign architectural style that was ideologically aligned with political power.

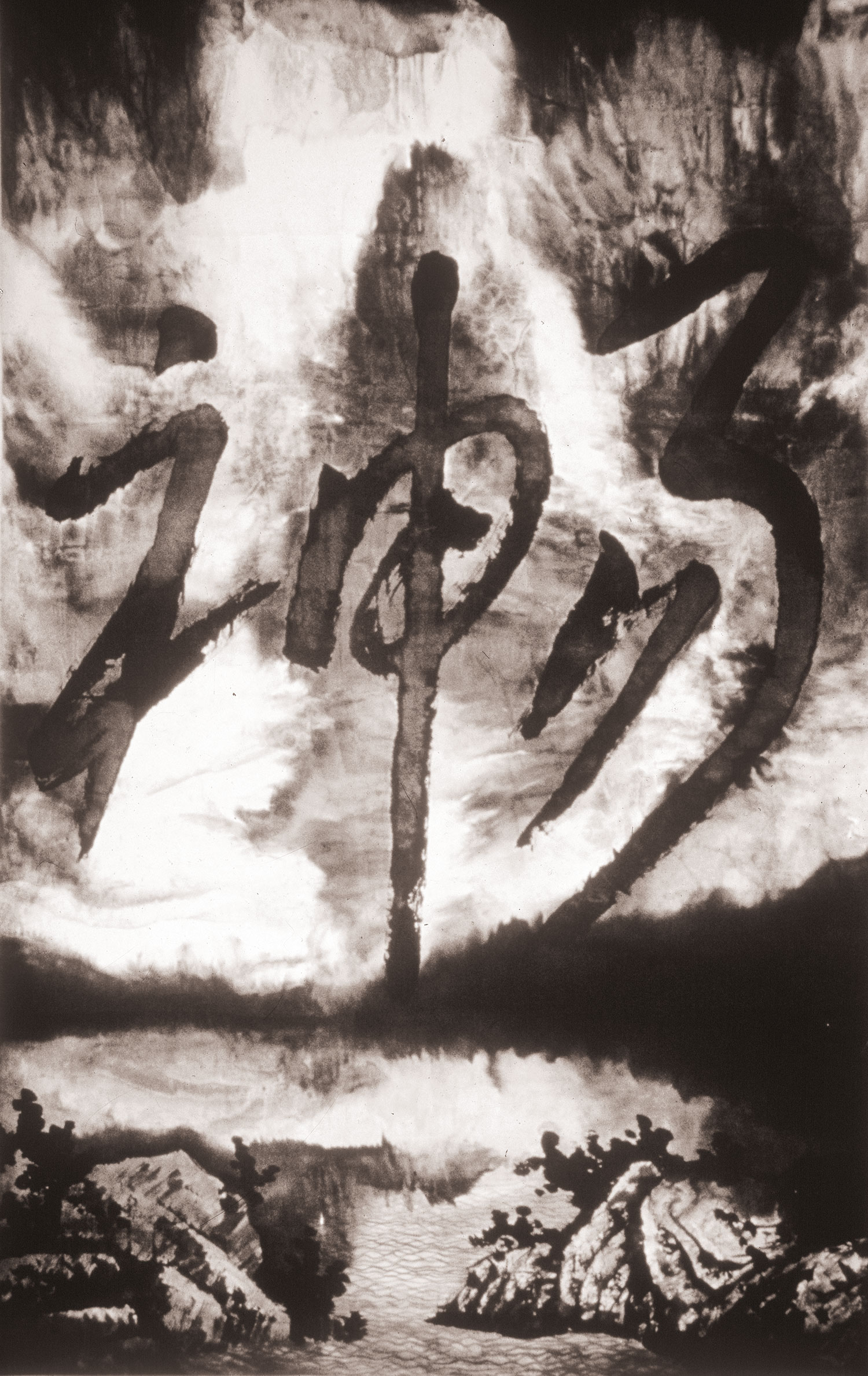

This Sino-Soviet dialogue constitutes a major preoccupation in Li Qing’s series “Neighbor’s Window,” as manifested by the recurrence of the Shanghai Exhibition Center among the paintings’ subjects. A colossal edifice, the Exhibition Center was completed in 1955, in order to commemorate the alliance between China and the Soviet Union. Moreover, Chinese Communist leaders conceived the building as an homage to their Russian counterparts, and hosted within it a didactic exhibition of Soviet economic, technological and cultural accomplishments in the years that followed the October Revolution. The building also appears in a singular painting from the series, Manuscript on Window (2013). Like the other pieces, in Manuscript on Window the artist rests a panting on a wooden window frame. However, contrary to Moscow Style and St. Petersburg Style, which feature close-ups of the building’s openings, here the painting frames a narrow perspective of the building’s side while at the same time disclosing design elements that uncover the Neoclassical flavor of Stalinist architecture. A truthful spatial distance between the interior point of view and the exterior subject — contrastingly, in Moscow Style and St. Petersburg Style the proximity will be gradually magnified in order to emphasize the optical illusion — suggests that the view is realistic, the “genuine” perception of a building “in the vicinity.” That the painting is a visualization of not just the coexistence of two entities — an anonymous Shanghai interior and the external Sino-Soviet Friendship Building — in the same urban fabric, but of their mutual, twinkly gaze, is further affirmed by the artist’s transcription of Chinese translations of Russian intellectual Osip Mandelstam on the window frame. Li Qing chose Mandelstam’s odes to his native town, St. Petersburg, which he replaced with Shanghai, his own. This gesture amplifies the semantic component of the painting — as if to say that the artist respectfully acknowledged the Sino-Soviet “friendship.” However, like in O. Henry’s short story “The Last Leaf,” which Li Qing frequently mentions among his references, in which the view outside a dying woman’s window of a transitioning autumn landscape is replaced by the identical image frozen in a painting, in Manuscript on Window, the artist replaces concrete perception with a mythopoetic account of history.

Manuscript on Window retraces the formula of a typical literati painting: it embeds in it a handwritten poem, and thus a calligraphic exercise, within a landscape painting. In addition to this tradition, one might identify as well references to realism in Li Qing’s painting language, as the buildings are meticulously studied and reproduced; and also to history painting, to the extent that the buildings boast a sociopolitical function. But how might one account for the window, the very support of the painting, which introduces the foundational element — the grid — of a distinct, indeed opposing language, i.e. geometric abstraction? The painting thus turns into a commentary on the tension between the anachoresis of literati painting and the aesthetic autarchy of social realism, in which geometric abstraction, or better, Western abstraction, is offered as the most efficacious form of reconciliation. Despite the layers of concrete references, the painting remains true to the history of painting: it is literally a window, delivering a scene beyond its frame, factually and allegorically. It “chews the fat” of tradition by enacting a semiological scan of the codes available to the painter at the moment of its making. At the same time, it raises the question of the conflicted identity of Chinese art within international art discourses.

This approach is more straightforward in later iterations of Li Qing’s paintings in window frames — for example, the series in which the painted images are taken from advertisements of Chinese artists’ exhibitions abroad. The paintings are always exhibited along with the actual advertisements, roughly cropped and placed in cheap frames, and, as in the case of the environmental installation Blow-Up (2014), displayed in a reconstructed public toilet. Here the artist assembles a decadent celebration of the international successes of his colleagues, exacerbated by the rank environment. The toilet echoes the logic of superimposition of historical layers that can be traced in the paintings, as it blatantly shows many renovations: a patchwork of tile surfaces covers the walls and the floor; two unpaired sinks are installed one next to the other; even the urinals seem to belong to different epochs… It recalls the recent past of Chinese history — its original template is sourced in Communist-era developments — however one that cannot be left behind once and for all, but rather forcibly “dragged” through the present. Equally, Chinese art seems to resist a canonical process of “modernization,” i.e. the questioning of identity politics embroiled in aesthetic tradition. Chinese art is typically invoked in the global system only by virtue of its “Chineseness.” It can only be “imported” by foreign players, as the advertisements displayed in Blow-Up suggest by promoting artists included in politically correct and “representative” gallery rosters. In this scenario, the eagerness for a prolific dialogue in the vein of the Sino-Soviet friendship seems anachronistic.

In an extremely self-referential art world and a market on its way to saturation, as is the case in China, a discussion around cultural openness seems rather urgent. In this sense, the recurrence in contemporary Chinese art of the figure of the window, and of “openings” of buildings in general, may suggest how this question is currently being played out. From Ai Weiwei’s Template (2007), a gigantic structure made of wooden doors and windows from demolished Ming and Qing Dynasty houses, to Song Dong’s Doing Nothing (2013–ongoing), sculptural assemblages of old, discarded windows, the window is indeed a recurring motif. But its reappearance seems to pertain exclusively to critiques of the “savage” transformation of the Chinese urban landscape. In a sense, it functions as a reminder of a cultural heritage in danger. An additional example can be found in Liu Chuang’s Segmented Landscape (2014), in which a series of metal window grilles, each boasting a unique pattern, is dramatically lit by spotlights; a gentle artificial breeze causes white curtains installed behind the grilles to flutter, upon which projections of the grilles’ patterns seem to sway. Liu Chuang’s windows solicit the idea of security, and thus private property, which becomes undermined by a to and fro scene of everyday life. It is an image that recalls the discrete observations of buildings “in the vicinity” in Li Qing’s “Neighbor’s Window” paintings: these paintings show Chinese cities that haven’t yet thrown their past away, that continue to activate a gradual, positive absorption of the past in the present. The only artist who is capable of documenting this process is the one able to place himself both inside and outside of history, both inside and outside of China.