To artist Lauren Halsey, South Central Los Angeles is the most creative place on Earth. Through her funk-inspired sculptures and installations, Halsey reimagines what space in South Central can be for Black and brown people amid rampant gentrification and displacement.

South Central, commonly referred to by developers as South Los Angeles or the marketable SOLA, separates Downtown Los Angeles from its surrounding suburbs. A historically Black community since as early as the Great Migration, the area has been resisting gentrification for the last twenty years. Today, with the development of the $5 billion SoFi Stadium — the most expensive sports venue in the US — residents are increasingly being priced out, and the culture and people who make South Central the creative enclave Halsey loves are on the brink of erasure.

Halsey has used her success as an artist to fund the Summaeverythang Community Center, a space founded on the ethos of empowerment through self-directed action. To date, they have distributed 14,000 produce boxes to food-insecure families since March. “It’s not about somehow becoming successful and leaving the hood,” Halsey states, “but staying and being blessed and making it the best place you can make it for yourself, your family, your neighbors.”

Halsey, whose family has called South Central home since the 1920s, is committed in her art practice to fighting against the stigma so often attributed to her neighborhood as a space of violence, something she says has been placed on her “out of fear, out of stereotype, out of myth.” Halsey speaks of South Central with nothing but love and admiration.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Leah Perez: I went to El Camino Community College, and you’ve mentioned before you studied architecture there. Now that you are coming full circle back to your architecture roots with The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (2018–), I am wondering where you see your work going from here on out spatially as well as in a theoretical sense in which you imagine the future of your pieces.

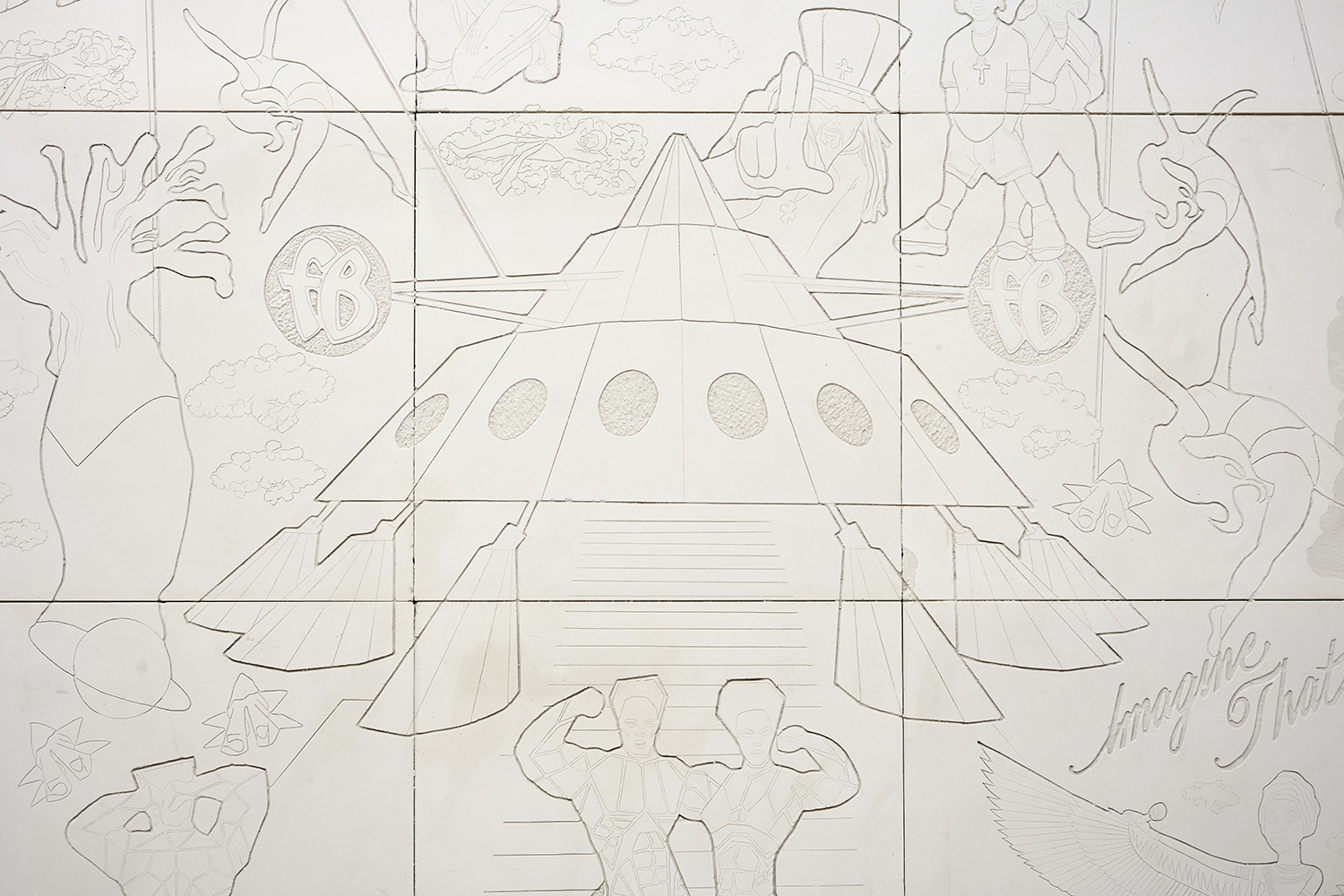

Lauren Halsey: For the past maybe three or four years I’ve been very consciously trying to professionalize my studio as much as I can. As far as setting up a place to do things, and setting up my studio with folks I enjoy building and sculpting with, I feel like I’ve finally reached that sweet spot. The crew is my girlfriend [Monique McWilliams], my best friend from childhood since I was ten years old [Emmanuel Carter], folks that grew up on the same street as me, around the corner, and studio assistants in a formal sense. I think of them as part of my aesthetic family, on the same rhythm with making. So that took a while to get there. And now that we are here, I feel like I am trying to, in this downtime of COVID, return now to older projects, to figure out new forms. So, for example, with The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project, for me that was a bit performative as architecture, as far as what the skin was. So I am hoping to get to walls that don’t just function as drawings but are also structures, superstructures as much as they are compositions of a place. Now we are getting closer to experimenting with concrete, so that the “hieroglyph” panels are not flat anymore. They’re not these 2-D compositions. They become full, 3-D almost Lego blocks, where I can address [the sculpture] as skin, but also composition, but also potentially shelter — aesthetic shelter. But to be honest, I’ve been really immersed with my food program. A lot of the experimentation to land on new forms has taken a backseat. I’m working the hardest towards sustaining my community center’s weekly food program.

Ana Briz: I love that you talk about architecture as not being outside of other forms of oppression, because it’s important for us to recognize, especially in this moment of uprisings, how architecture plays a role in the oppression of communities. You have referred to yourself as a caring architect. Could you talk more about how care works into this fantasy world that you’re building?

LH: I try to not be so seduced by the goal or seduced by trying to achieve monumentality. And having empathy as far as context, and how I contextualize the process, the work, the people, the material, the archive, all these things with love and pride in mind. That is exactly why I work with who I work with, because so far it’s been a beautiful and romantic yet difficult social way to achieve a sculpture, and hopefully an architecture one day.

LP: To follow up with this idea of caring architecture, I am really curious about your “funk mounds,” these lumpy white spaces of sorts, as we often think about the museum as being this white-walled space. How did you come about using these very curvaceous forms as your walls?

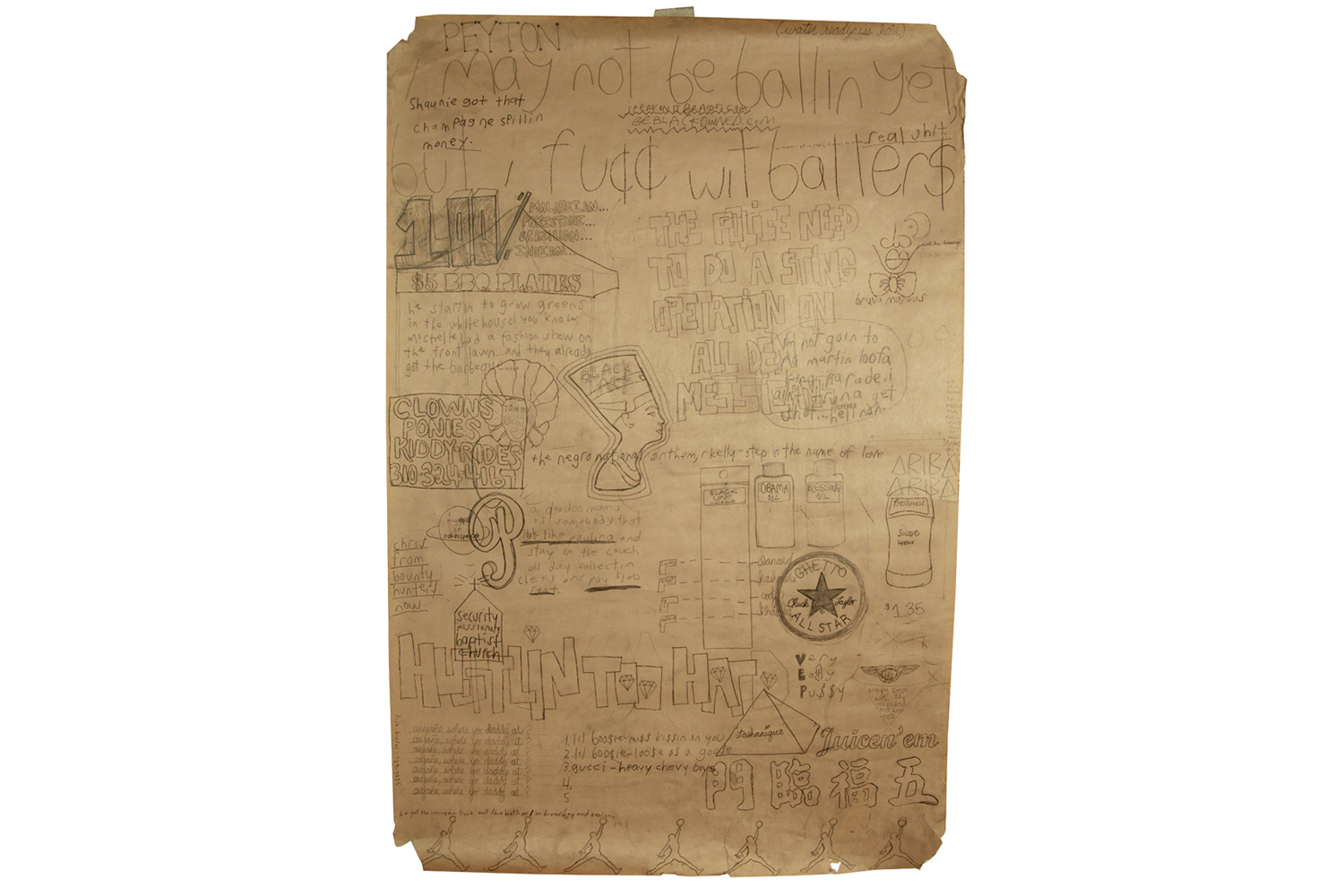

LH: When I was in grad school, I lived in my studio, and I started building the cave as a container for myself. It became an aesthetic cave where I displayed a lot of the archive I was collecting — some of it intentionally as an archive, some of it just things I liked and would display for myself. Then it became a cave where friends and I would gather, like a kick-it spot where I created these waterfalls, and I found it to be really beautiful.

At the same time, I was learning about the Mogao Caves, these Chinese grottoes, and the function of the cave as a warehouse for culture. Having moved back to LA, having seen my neighborhood and so much of LA totally rearranged and on the brink of erasure, and people taking new migrations outside of LA County, I started thinking again about making an experimental maquette of a place to hold our archives and our stuff, because there isn’t one. Of course, there are libraries and research archives, but I mean our aesthetic stuff — the objects we make, our myths, our scents, our sounds. So I started building it with my best friend, and it grew to include my girlfriend and my cousins, and it became this intuitive and collaborative sculpture that anyone could be a part of. It wasn’t about having a certain education or craftsmanship. It was just about using our hands, and that brought people together in a really beautiful way.

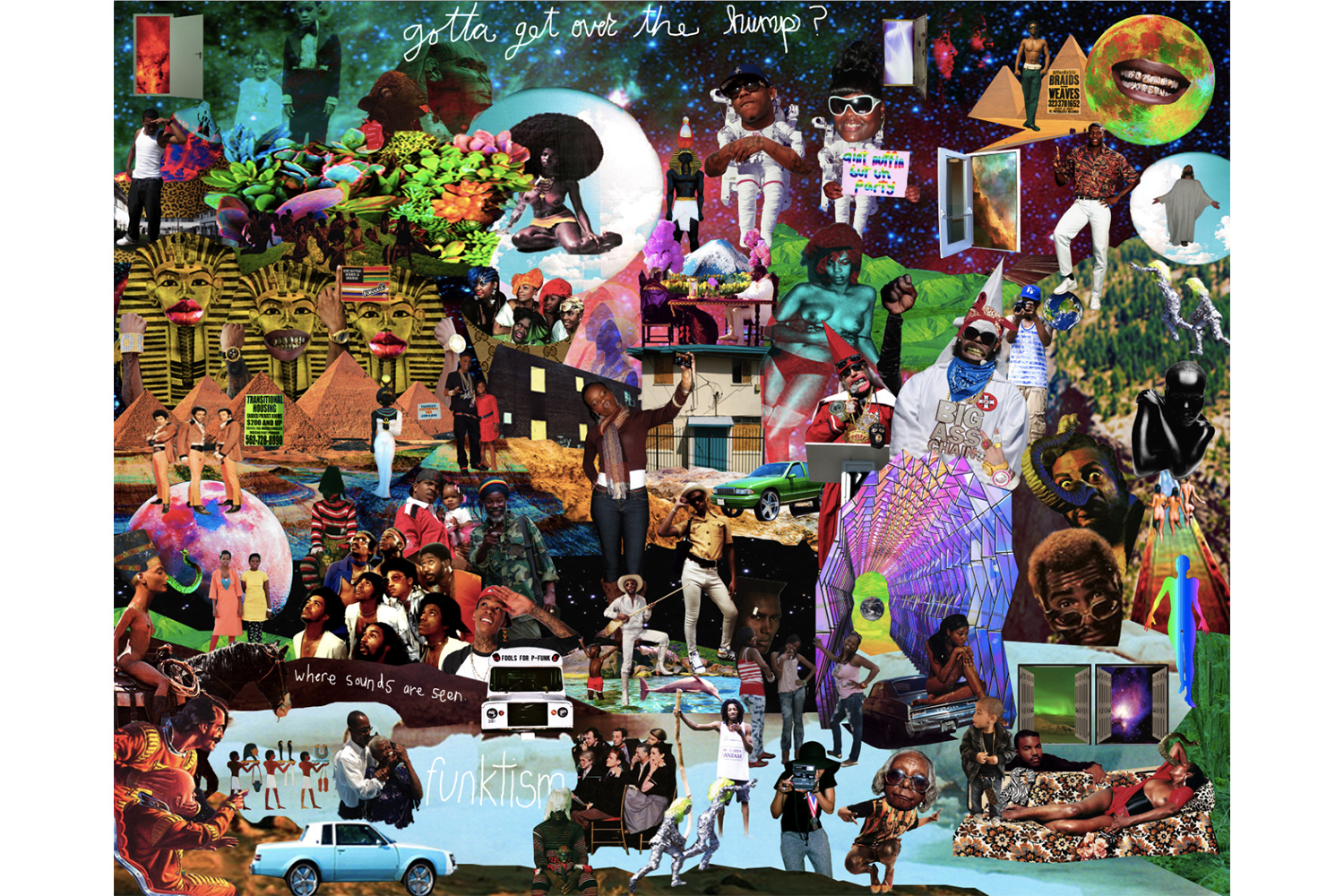

AB: We get the sense of urgency of having built this space as a repository and archive — and linking it to the Chinese grottoes makes so much sense, to then work collaboratively on this, and it makes me think of what the future holds. Positioning your work as an afro-futurist, what does afro-futurity mean to you right now?

LH: For me, I guess I feel energized by the genre. Pre-COVID-19, I always thought, “I’ll get there, the community center will happen, I’ll reach my scale. I’ll eventually build an architecture.” But I feel more than ever excited about going for my funk and building these very aspirational worlds that I have no idea how to achieve. I think before I was lost in the sauce of the myth of “We’ll beam into the stars and start over!” and now there’s this immediacy of now or never. This sort of energy I carry with me every day. And I am realizing that no one really gives a fuck.

Before [COVID-19] I was thinking of afro-futurism as a destination and I would land there and that sentence would be finished by the time I leave this planet. But now I’m just in a rush to get to afro-future now, because it’s already too late.

I feel energized, but I also feel really sad, because that means a lot of labor, capital, soul work, pain. Realizing the world is not what you thought it was, and you can work so hard to try to create equity, but they’re still developing a luxury condo around the corner that’s sixteen thousand dollars a month, people are still getting kicked out. And that’s just the first of many to come with all of the new infrastructure and investment I’m seeing here on a global scale. So now I’m trying to put all my ideological hopes into practice in a tangible way. Whether that means in a sculpture, a produce box, or an after-school program, but doing it right now, whether we have the resources or not.

LP: Your archival and community work with Summaeverythang is very inspiring. South Central LA has such a deep-rooted Black history. What do you think is the best way to preserve this knowledge for future generations, despite the city changing by the second?

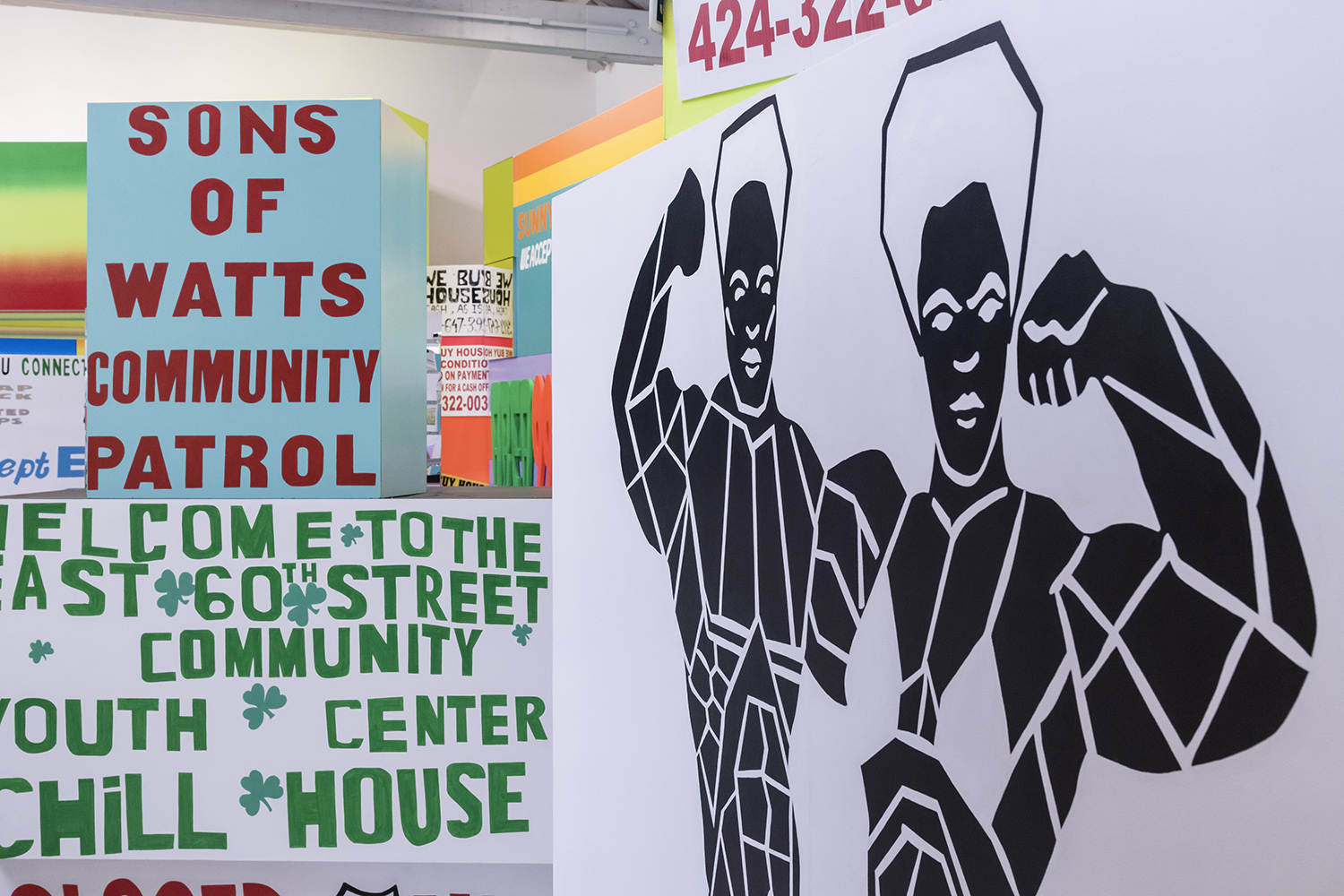

LH: We need space to do that. We need our spaces. And we need our people to be caretakers and custodians within these spaces to hold our archives. I see my community center functioning as that, so by the time my time on this earth is over, hopefully I will own the property and there will be some sort of trust, so you may be able to come in and see a decade’s or life time’s worth of our stuff— I’m making it up — but for example hundreds of bundles of incense from such-and-such or this era in the neighborhood. Or a whole — and I’m not making this up, I’m really working towards it — but a collection of paintings from Pasacio tha King [Pasacio Da Vinci], the sign painter from around the corner. I don’t know who is going to do it, but I know I am very actively tending to these archives and participating in them, and buying, sourcing, and curating things to the best of my ability, so that one day I can leave it in a space and hopefully someone who comes through the community center will be the custodian of that.

AB: The objects you are archiving are unfortunately materials that don’t get archived institutionally, and I feel like in your work you are constantly defying what it means to be institutional. Can you talk about your participation in the art world, making objects that are shown in galleries, but also constantly thinking about the public space and advocacy for access to these things?

LH: I care about art history to an extent, and I care about the works that I make of and for South Central existing in an art-historical canon a million years from now as a statement or declaration that folks from here built this thing — it’s important.

But what drives me and energizes me is the potential of all the resources, the art sales that I make here and there to amplify the knowledge, resources, funds and energy that I can recycle back into my neighborhood.

Though I have parents that have worked extremely hard throughout my entire life, my parents aren’t Puff Daddy. So being involved in the art market with autonomy, I definitely have a say where my work lives and who gets to live with it. That exchange of capital has to happen. I participate in [the art market] and it’s important, but I see it as a way to facilitate and get in place the things I need in order to function as a happy human in my neighborhood. I see it as a tool.

When I was at El Camino, I tried to hustle printmaking to sell prints outside of the Staples Center, depending on who was performing. And I realized very quickly that if I could sleep at night and exchange what I’ve made to have money to then do something transcendent with that money, I would be okay with that. And so that’s how I position it. You have to constantly check in with one’s ethics and moral compass. At the end of the day, the class and cultural differences could not be further apart from what my life experience has been. It’s mind blowing.

AB: One of my favorite works of yours is Slo But We Sho (Dedicated to the Black Owned Beauty Supply Association) (2019), which was shown at Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles in “Punch,” and I love the work both for its content, meaning the Pan-African flag, but also for the materiality of the hair and the tactile nature of the material you are using. Can you talk more about this piece and its dedication?

LH: I started consciously noticing when I moved back [from college] that the knick-knack stores, the fish markets, the beauty supply stores, the liquor stores, the mini-markets… aren’t owned by folks in the neighborhood. And at the time I was making works at school where I was just making these portals into, for me, a funkadelic sphere, and I was using the hair as that, and I would put fans on it. Long story short, I ran out of hair. And I’m all over LA looking for these special neon and pastel colors, having an incredibly hard time, experiencing all the racism in the world, and I was just like, “Enough’s enough. Let me go to the distributor to buy the hair so that I don’t have to deal with this.”

[My girlfriend and I] go to the distributor — we don’t call, I didn’t think you had to call — and it’s this warehouse. We knock on the door, and this Korean dude comes to the door, asks, “Hey, can I help you?” looking shook, like how did you find me. I say, “Hey, I just wanted to come in and buy some hair. I thought this was a store.” And he was like, “What do you wanna buy hair for?” And I was like, “For my head?” Now the door’s open, he says, “Come in,” and we are in this huge-ass warehouse. He’s kind of nervous, and my girlfriend and I are like, what is this energy about? So we sit down in his office, and you know that part in the thriller where at the end of it you go into the serial killer’s room and they have newspaper clippings and pictures of the person they’ve been stalking? It was like that but for Black women. It was the most beautiful but weird, kinda scary installation of Black women, every sort of aesthetic era, every style, natural, weave, straight, braids, finger waves, cornrows etc. And he’s looking at us scared, as Black women, though he has studied us. So I say, “I wanna buy a thousand packs of hair for myself and for my art.” So he asks, “Well, do you have a business?” And I had just moved into my studio, [so I say] “I’m not going to tell you my address, but here’s a picture of it,” and I showed him the picture. And he’s like, “Well, do you have a wholesale license?” And my girlfriend’s like, “Yep, we do.” So then we realize it’s a game. We have to fill out an application so they can decide if you can spend your money at their global business to buy hair. And in that moment I was just crushed, because I realized the reason why I haven’t seen Black-owned beauty supplies all over South Central isn’t because we don’t have the credentials or the space or we can’t do it, it’s because we literally have been locked out of a market so that we can’t compete. And on top of that, we are limited as far as choice to what they think our palette should because now they’re curating aesthetics for us. So they are studying us as designers and distributors of this hair based off weird myth and, I guess, ideals that they see for our beauty.

I started doing more research and I just couldn’t find too many [Black-owned beauty supply stores] because we’re locked out of a market. And then I came across the Black Owned Beauty Supply Association, and so I’m thinking that’s going to be another project later in life if I have the funds to do it, where I’ll hire a Korean American friend to pretend to be myself so we can buy all the hair we could possibly buy and give it to Black women so they can begin to open their own businesses. So that was the cause, and hopefully the effect of it will be more businesses with free hair that the community center will provide for free and for braiding classes. That’s just one of many examples.

AB: Akin to Nipsey Hussle’s legacy and his commitment to celebrating the people of South Central, I view your work through this lens of art as a lifeline for culture and people. Could you talk about how you work through your artistic practice to defy the negative connotations art is given, as well as speaking to how South Central is the most artistic place that you know?

LH: I think that comes out pretty naturally because I’m doing it and making it and experiencing South Central with the same people I experienced it with, without all the baggage. So we don’t feel the gloom, like we have moments where we’re just driving and we’re like, “Fuck. I love the Eastside,” and my best friend knows exactly what I mean. You go outside and it’s the ice cream truck, and it’s the children, and its beauty and they’re playing tennis in the streets, like I did when I was a kid, and they’re playing — they have go-karts now. It’s the corn man, the tamale man, it’s just all of this beauty.

Of course, there’s other stuff, there’s violence here and there, but that doesn’t dominate my experience here. If anything, that’s put on by other people for me. There’s struggle, there’s hardship, there’s challenges, but there’s also other stuff.

LP: I love that. I think that you are pushing back against a narrative that has portrayed South Central as being this place that people are trying to get out of, and you show deep admiration for it, and it’s clear you want other people to see it too.

LH: I remember one of the last things Nipsey said to me and my girlfriend and my best friend Emmanuel — this was two days before he passed — and we both were like, “Yeah, 100%,” he was like, “I love the hood, I’m a hoodrat. I love driving around and smelling the scent of Louisiana” or Woody’s or knowing I’m going to see this person. There are these certain local landmarks that are so private to South Central, that we have all accepted, like, “This is the spot. This is ours.” It’s beautiful.