The first experience of Laure Prouvost’s work can be unforgettable. For me it was marked by her voice, heard shouting from the top of Paris’s Palais de Tokyo. She was taking part in Alex Cecchetti’s so-called performative poetry seminar, Nuovo Mondo, held over three evenings in the summer of 2014. As dusk fell, Prouvost called out for her “grandad”; a lemon, carrot, onion, and tomato rained down from the roof; and she soon descended the spiral staircase to scour the dirt in an overgrown patchwork of community garden plots.

“Grandad,” once a close friend of Kurt Schwitters, begins Prouvost’s tale: he had allegedly dug a tunnel from his shack in Northern England, and had recently disappeared inside. “MY GRANDAD LAST CONCEPT WAS TO DIGG A TUNNEL TO AFRICA WITH OUT BEING NOTICED BY AUTHORITY,” Prouvost writes, in her signature black-and-white text in sans serif all caps, punctuated by childish misspellings and “Franglish” syntax. When the lemon, carrot, onion, and tomato fall into her room in the middle of the night, through holes in the ceiling that match the shape of the produce exactly, the artist implores: “It’s a sign from God! Grandad is alright!” Grandad’s saga and Grandma’s vigil in the couple’s mud-filled cabin drive the artist’s enchanting video and installation Wantee (2013), commissioned by the English arts organization Grizedale Arts and shown at Tate Britain as part of Schwitters in Britain. The seminal work won Prouvost the 2013 Turner Prize, in combination with Swallow (2013), her video and installation work for the Max Mara Art Prize for Women and the product of a fruitful residency in Italy.

This year, Prouvost is again finding inspiration in Italy, representing France at the 58th Venice Biennale. After Annette Messager and Sophie Calle, Prouvost is only the third female artist to take over le hexagone’s Beaux-Arts pavilion. In her interview with French Pavilion curator Martha Kirszenbaum, who has long been complicit with the artist, having organized presentations of her work from Paris to Los Angeles, Prouvost situates her project for the Biennale firmly inside the matrix of her intuitive practice: “I would say that my work for the French Pavilion is part of a continuity, because my work is organic and everything is connected, whether it be in its intention or its form.”[1]

Language, most often French-accented English, is at the heart of Prouvost’s work. In her performances, as I saw at Palais de Tokyo in 2014, she uses her voice as a motor or a purring engine, and at times like a siren, driving her narrative to panic mode. Likewise, in her videos, her voice, combined with percussive montages of text and image, renders intensely immersive work. In an interview with London-based critic Adrian Searle, just following the release of Swallow, Prouvost said of video: “As a maker you can be quite controlling … I think if you want to control an emotion, it’s quite an amazing tool.”[2] For this work, the idea was “to show the taste of the sun.” Blurry images of a yawning pink mouth punctuate idyllic scenes of bare feet on lush grass, Prouvost and her friends bathing naked in a waterfall, and freshwater fish gorging on raspberries. “Turn around,” the artist intones in the voiceover, “the fruits are naked.” Prouvost knows the power of her own voice, as seductive as ripe fruit or the curves of a nude body. “FIRST I MUST SAY I LOVE THE SOUND OF YOUR VOICE” flashes as a text frame in her video We Know We Are Just Pixels (2014).

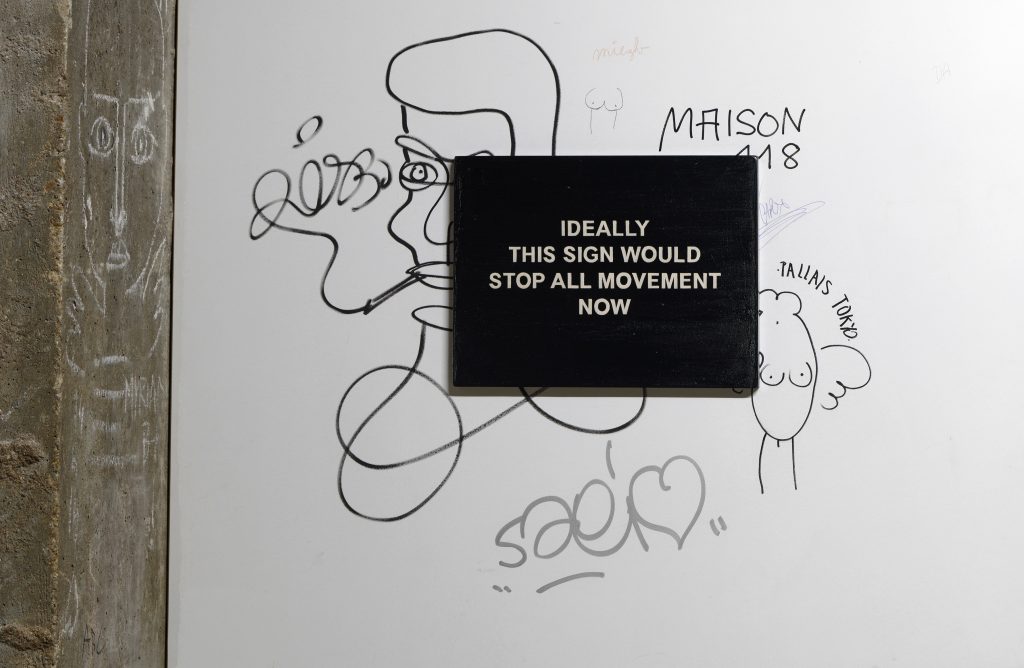

Many of Prouvost’s text paintings, or “Signs,” begin with the word IDEALLY. With this linguistic shift away from the real, she insists on asking how the art institution, artworks, and the simple gestures of daily life could be improved: “IDEALLY HERE THE ROOM WOULD BE SUPER MODERN WITH SHARP ANGLES FULL OF MIRRORS AND WINDOWS” (2014), “IDEALLY THIS SIGN WOULD TAKE YOU HIGHER” (2017), “IDEALLY THIS SIGN WOULD TAKE YOU IN ITS ARMS” (2011). “I am just hinting and suggesting possibilities,” Prouvost explains, “the audience is making its own image in its head.”[3]

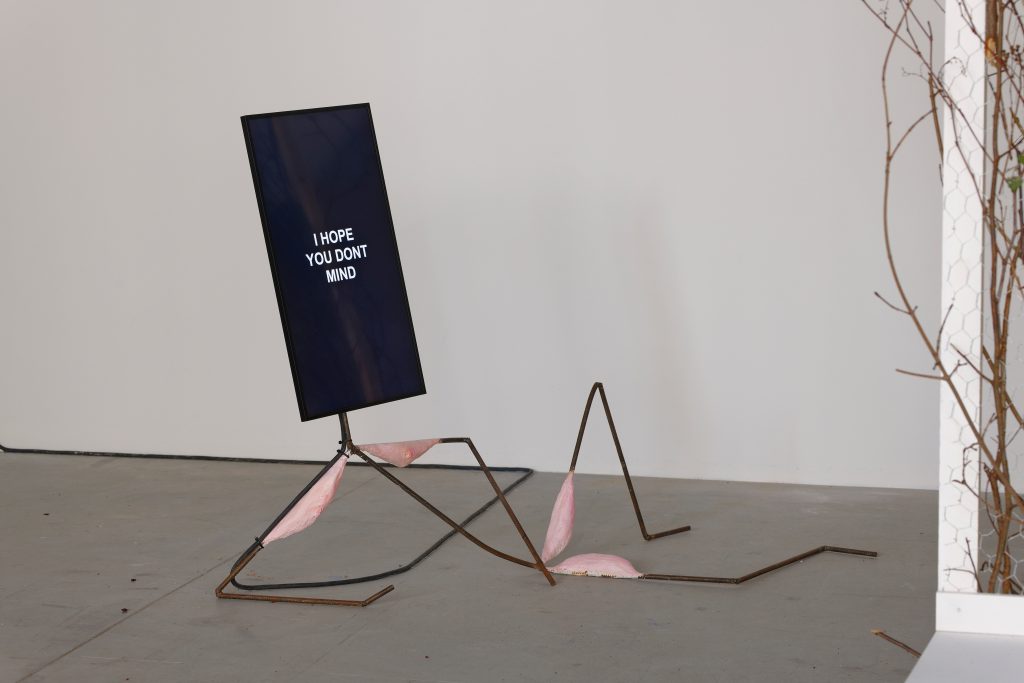

Prouvost’s recent sculptures from the series Parle Ment (2017), the title a Frenchization of the English term that becomes “Speak, Lie,” could be described as life-sized stick figures. Made of black metal bars with flat-screen video monitors for heads, they were presented in the exhibition “LOOKING AT YOU LOOKING AT US” at Nathalie Obadia’s Paris gallery in 2017. Poking fun at schematic representations of gender, on The Parle Ment sitting Woman reading a letter (2017), for example, Prouvost indicated breasts with pink papier-mâché blobs drooping from the sculpture’s metal frame. Meanwhile, The Parle Ment Metal Man Offering Drinks (2017) held a small wooden tray with four porcelain teacups and a floral teapot. The digital text on the works’ video-monitor heads addressed the visitor with needy phrases, practically begging for a space of dialogue and exchange: “I HAVE BEEN TOLD TO STAY HERE AND RELAX,” “I WOULD LOVE TO WALK AROUND HERE WITH YOU,” “I WISH I COULD HUG YOU.”

Meanwhile, together with artist Jonas Staal, Prouvost created L’Aube’s cure Parle Ment (2017) (pronounced the obscure parliament), an installation for curator iLiana Fokianaki’s State (in) Concepts at the Kadist Foundation, Paris. Neat black structures hung with curtains (Staal) functioned like stages for scraps of dialogue and forms that Prouvost was also showing at Obadia. A huge pink tongue, that Prouvost had made in in resin and foam, spread wide at the center of the installation. A recurring motif in her videos, in this context, the vital mechanism for speech was positioned as the linchpin of the artists’ governing body.

While Grandad was digging, Grandma stayed behind to serve tea, sometimes spiked with gin, and work on her tapestries. The title of Prouvost’s work Wantee is a reference to the patronizing nickname for Kurt Schwitter’s partner Edith Thomas, so often did she offer her guests a hot infusion. “Want tea?” Prouvost continues to ask, mocking not Ms. Thomas but the macho culture that came up with her moniker. Meanwhile, Prouvost’s ambitious, richly colored tapestries are formal metaphors for the tales Prouvost spins, and the expansive, enveloping environments that she creates in her installations and videos. At Palais de Tokyo last summer, Ahead of Us (2018), a three-by-four-meter tapestry, embellished with wooden branches, pictures what looks like a table from Grandma’s cabin set for a tea party with homemade ceramics. The block text that borders the image reads: “IMAGINE US ALL MAKING IT TOGETHER, FORAGING FOR BERRIES, CATCHING PIGS — WE’D ALL BE SWEATY, SCRATCHY, AND DIRTY FROM RUNNING THROUGH THE BUSHES.” The power of the collective emerges in Grandad’s absence, and Prouvost allows us a glimpse at a kind of feminine utopia uniting around domestic rituals and artisanal media.

“Speak,” a group exhibition at London’s Serpentine Gallery in 2017, coincided with the institution’s survey of late conceptual artist John Latham, with whom Prouvost worked as an assistant almost twenty years ago, following her studies at Central Saint Martins. Appropriating the title of an experimental film by Latham from 1962, the show brought together work by Prouvost, Tania Bruguera, Douglas Gordon, and Cally Spooner. Prouvost occupied a darkened space at the center of the gallery with the installation end her Is story (2017). A series of objects on plinths — glass, teabags, branches, butter, and the ubiquitous lemon, tomato, onion, and carrot — were alternately illuminated by spotlights and the melodic intonations of Prouvost’s storytelling voice. Latham also worked with books and text, famously inviting his students to chew and spit out the pages of Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture. For Prouvost, as well, language and written text are her most pliable media.

Tapestries lined the tunnel that formed the entrance to Prouvost’s “Ring, Sing and Drink for Trespassing” at Palais de Tokyo in summer 2018, a monument to Grandad’s conceptual dig and Grandma’s tireless work. There were hand-glazed ceramic teapots scattered about, the quartet of fruits and vegetables, as well as dark raspberries ripening on car mirrors. But here at the center of the exhibition, it was the female form triumphant, a fountain of oversized resin breasts as the centerpiece for a summer garden. We Will Feed You (2018), Prouvost explained, is “extreme, feminine symbolism — a surreal, slightly grotesque fountain of nine boobs.”[4] The tunneling story is a charmingly convenient, deceivingly innocent, way to bury les maitres.

Prouvost is often presented as singular, but there is a rich lineage in which her work could be compellingly situated, starting first perhaps with the early works of Gina Pane. Earthbound and bursting with material and text, Pane’s first large environment work, for example, Acqua alta / Pali / Venezia (1968–70) presents a forest of tilting Duralinox columns emerging from pools of mud, and covers the surrounding floor, wall, and ceiling with the Italian words for high water, poles, and Venice. The hypermateriality and urgency of Pane’s work echoes throughout Prouvost’s practice. Although the emotional gravity of Ana Mendieta’s performance work is counter to Prouvost’s relative lightness, both artists work with their own bodies in the landscape, both audacious in their own times. One might draw a more formal parallel to the work of Martha Rosler, particularly her video Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975). Rosler’s sign in white chalk on a handheld blackboard that announces the title of this work with a deadpan seriousness resonates in Prouvost’s “Signs,” the anxious heads of her “Parle Ment” sculptures, and the text screens of her videos. And Prouvost’s breathy voiceover for her video If it was (2015) is an ecstatic riff on Andrea Fraser’s provocative Little Frank and His Carp (2001), performed at the then newly opened Guggenheim Bilbao. “In my museum … at night,” Prouvost intones in If it was, “everyone who works here kisses the floor everywhere … you’ll be asked to touch everything, even lick … we don’t go to church anymore, we come here on Sunday.”

This summer, worshippers will head to Venice to see “DEEP SEE BLUE SURROUNDING YOU / VOIS CE BLEU PROFOND TE FONDRE,” Prouvost’s project for the French pavilion, in which she appropriates the motif of the octopus. The cephalopod already appears in Prouvost’s work This Means (2019), a two-meter-tall Murano glass sculpture, currently part of her show at M HK Antwerp, as well as in her recent video Lick in the past (2016). Prouvost is not the only contemporary artist to use this marine metaphor for the animalistic dynamics of our social-networked moment. The Kuwaiti-born, now Beirut-based, artist Monira Al Qadiri recently explained that in our age of “hyperconnectivity, what creature must you become in this landscape? You must practice oktopolitik.”[5] Al-Qadiri also shares Prouvost’s use of humor, paired with a deliberate nonchalance that nearly masks both artists’ well-structured critique of the myth-making that goes into the creation of art history, gender, and art speak. Both women seem to see a solution in the work of the collective. In Venice, Prouvost hopes that “every spectator will become a tentacle of this project … Language opens to an infinity of surprising possibilities.”[6]