Lafawndah, sometimes known as Yasmine Dubois, is intent on holding space for growth in her music, traversing genres, and uncovering impenetrable musical categories. She is closing in on two very separate avenues in her music at the moment, far from the experimentalist aperture of her 2020 album, The Fifth Season. However, such abrupt turns are what we have come to expect from an artist who persistently reworks and recontextualizes the boundaries that define her practice. What she terms “developing new geographies” is made evident in all her collaborations, live performances, and compositions. Lafawndah freely explores everything from robust pop-orientated melodies to minimalist sonic tensions, expanding her musical cosmologies and ways of making. Her performances are attentive, porous, and resonant with musical lineages shaped by the localities she encounters.

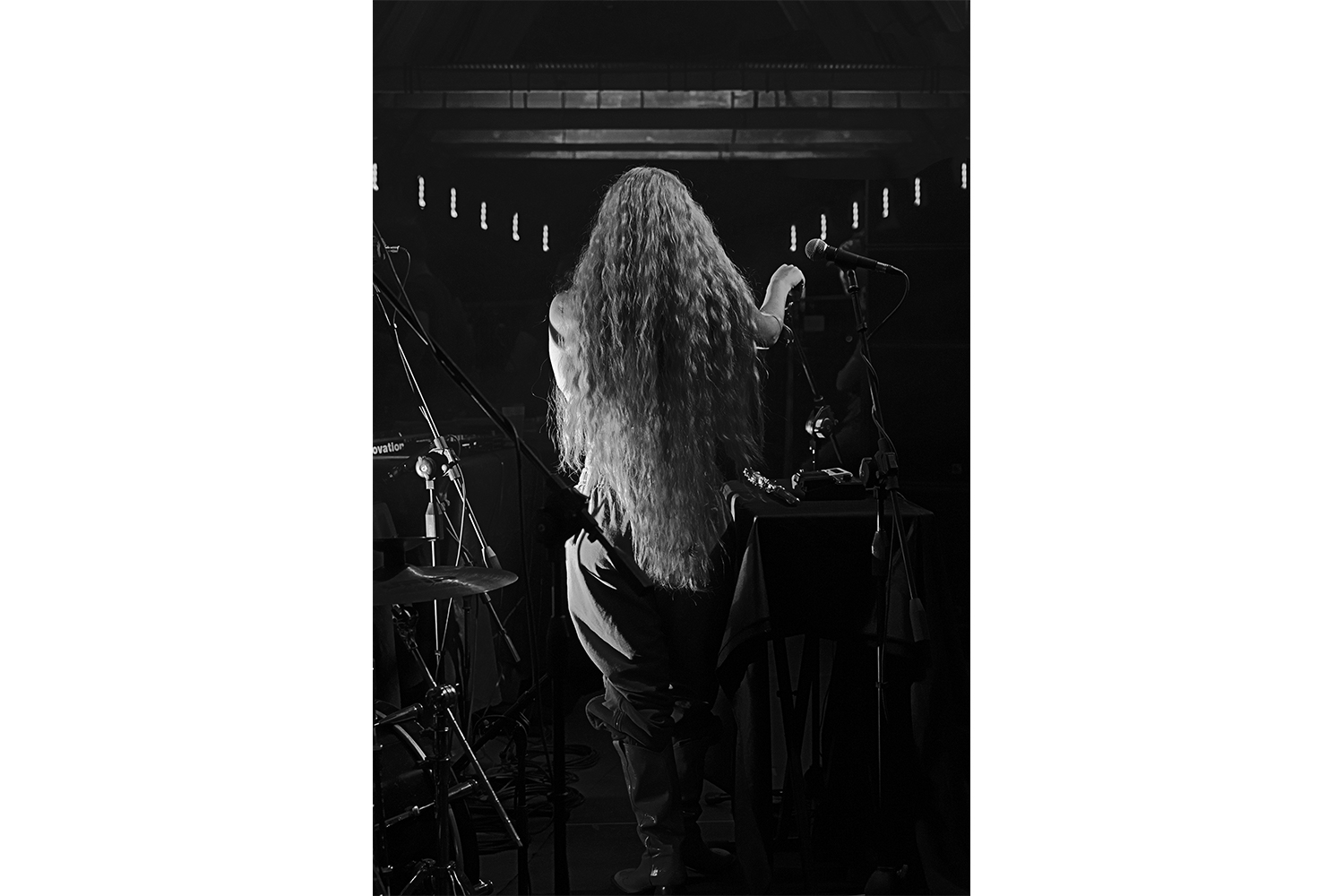

I spoke to Lafawndah after she opened Italy’s Terraforma Festival in early July. Although for Terraforma she presented music from her past releases, performed with ongoing collaborators, Lafawndah has arrived at a new juncture and impetus in her work — a seemingly unexplored and exciting synthesis of interests that premiered at Sónar in Barcelona. We discussed the responsibilities she has to her collaborators — an eclectic mix of visual artists and musical ensembles that seem to be in constant flux — and what roles they serve for her as well. Today she is working on two major projects, operating between extremes: as the insurgent front woman for her new material; and as the architect of a large-scale opera titled The Descent of Inanna, set to premiere sometime next year in Paris.

Jazmina Figueroa: Let’s start our conversation with your performance that opened Terraforma at Villa Arconati outside of Milan: a beautiful presentation with the band that you assembled for The Fifth Season. How was it performing this after the premiere of a newer work at Sónar?

Lafawndah: I need things to constantly be rewritten, reconsidered, and in movement. I find growth in thinking about what I say and where. For Terraforma, there was the specification of opening the festival, which is a very special slot, and it was the first time that everyone from this community was able to come together after two years. I put a lot of thought into what would be the right thing to offer, to send people off on a three-day journey.

JF: Your band is always changing. Can you tell me more about the group you had with you at Terraforma?

L: I’ve been making music with Sébastien Forrester. He is a drummer, percussionist, and musician based in Paris. We’ve known each other for a long time, but we started playing together when I moved back to Paris. For the past year and a half, no matter what the formula is — orchestral or club or punk or whatever the thing is — it has been me and him. When I lived in London I was doing all my shows with Valentina [Magaletti]. She’s one of the best percussionist-drummers in Europe, for me — if not the best. To have a show where my two partners in crime could be in dialogue with one another was important.

JF: A sort of coming together.

L: Yeah, I don’t really think about that show as being attached to a record as much as it was more of an approach. With [the pandemic] came a lot of questions. First of all, how can we pretend nothing happened? People put things on pause and are now pressing play — frozen and then instantly unfrozen. I don’t feel that way at all. I am quite transformed not only by what we experienced, what was experienced communally, but what changed on an individual scale. I find this hard to ignore. For this show I thought: How do I want to be on stage? What do I want to convey? After these two years, I didn’t feel the need to be the front woman. I wanted to reconnect with my instrument, manipulate my voice, and bring something like a caress. Everything is created in the moment as well, with no backup tracks at all. It’s all live, which I’ve never done before.

JF: Oh, how was that?

L: It feels like a noise band sometimes — super bare and very fragile. When you’re just two or three people creating things live, you can’t hide behind anything. If you fuck up a loop, then you fuck a loop — you know what I mean? I wanted it to feel fragile. To convey, “YEAH! I’m coming back strong!” is a lie. A lie can be interesting, I’m not some supporter of the truth, but some lies are more interesting than others. And I think that where I’m at energetically is not necessarily an interesting lie.

JF: You could describe the structure as a call and response between you and the others on stage.

L: Absolutely, yeah. There’s space for that. It’s all based on a composition that’s being made before your eyes. It grows this way and we kind of move through it.

JF: The track “Stillness” on the album The Fifth Season, is a direct reference to N. K. Jemisin’s sci-fi novel. What was it about that story that resonated with you?

L: Yeah, it was really strange. People think that I wrote The Fifth Season during the COVID lockdown, but I finished it in December 2019. The Fifth Season was very different from my first record, which was more controlled and written, in this one I decided to work with improvisational techniques and be open to what would come to me. First records, for a lot of musicians, come through pain — it is the first time that you’re presenting yourself in the world which is nerve-wracking. I felt very consumed by this process. After this summer, I’m going to work on something else — I’m closing this chapter of the past year and a half, and coming out of this isolation that we’ve been in, and this fragility emotionally stored in my body. I was so sick for the past two years. There were a lot of things that I had to work through. This record is a testimony for when you let yourself run with it. At no point was I obsessed by this book; this book was just in my life while music was being worked on, and all these sorts of things invited themselves on the record. It all belonged in the record. I’m extremely sensitive to world- building, and the relationship with geology and stones is strong in this book — there are people in her book that are made out of marble.

JF: That’s a beautiful image.

L: Sometimes you come into contact with works of art that take you in but in an enclosed way — they keep you with them. Then there are works of art that suck you in to expel you back out with like a thousand new uses or new ways of being yourself. I think that record was a premonition, letting things come through. I’m learning how to practice making room for that. The poem used for the third song on the record, “You At the End,” is not a poem that I’ve had in my life. One night touring with Kae Tempest, I opened a book from their merch stand and here was a poem called “The woman the boy became.” When I saw these words, I wished I had written them, or I felt I had written them in another world. Any time I’m compelled to take somebody else’s words or work in general, like music or melodies, it’s because it should come back to the world. The book and the poem are absolutely unrelated, but they come through me and it is not really my decision.

JF: As if you’re doing an analysis or a rewriting?

L: Analysis calls the intellect. It doesn’t happen that way — it was a whirlwind of connections. I really love titles, like The Fifth Season, that open up possibilities. My art in general can be an excuse to get familiar with other ideas. I’ve always appreciated artists who are generous with what inspires them, the title can say something more — infinite images come to me when I think about all that makes up an extra season.

JF: Your performance at Sónar was a premiere and a departure from what you did in The Fifth Season.

L: I have been feeling clear about what this new material is for a few years now. So it’s time for me to get on with it.

JF: You have a different, kind of heavier weight to the sound in this new work. Maybe not as much space…

L: I don’t think that’s true. I’m a maximalist when it comes to composition. I love the Baroque, I love sounds upon sounds and layers upon layers. I have been very diligent in being as bare as possible in the past two months. What happens when you just keep the bones? No fat, no lace, and no beautifying. Just the bones. That’s been my motto. There’s more space than ever. This interview with Courtney Love I read a few years ago initiated and sparked this next chapter. [Love] said there are more reasons for us now to be outraged, and yet there’s a lot of inoffensive music. She’s very surprised by passivity, general compliance, and slickness. She was talking about screaming and how it’s important, she thinks, for every musician to find their scream.

I’ve been thinking about the history of punk music, what it ignited, and what purpose it served. Not as something nostalgic. It is every generation’s responsibility to create new languages. I still feel very close to what punk or grunge music brought out in me growing up. I don’t feel that I moved on from the disruptiveness of it. As a teenager, I never had the opportunity to connect with music that was made by people who looked like me or who had similar lives as me. There was always this discrepancy between feeling very close to how things were expressed and something that felt very far away. I think the new material is trying to reconcile that.

JF: You’re attentive to context and genre. What do you think you’re paying attention to here? Raw energy? Or a version of yourself from before?

L: No, I don’t think it’s a version of myself. I want to experience collective release. Hopefully, if I release, you release. And if you release, I release. It’s an infectious, vicious cycle. I’m thinking about the energy of the moment that’s being shared and how to give in to that moment. I think a lot about rally songs too, and when things feel very lonely or helpless. What music can remedy that?

JF: This goes back to the call-and-response working method.

L: I like the idea of being porous; the intention is to bring you into it.

JF: I guess that’s what you mean when you say there is still a lot of space in the new work.

L: Exactly, these spaces. Punk music and, of course, hip-hop, in their early stages were connected. I have always existed in spaces that were extremely masculine. In my own experience, if you want to go into a mosh pit, a majority of what’s offered to you in popular culture, on the radio, the imagery shows you’re going into an extremely masculine space — depicted as the master of collective release. It’s not a counterpoint because that wouldn’t be interesting. With the experience and community that I have around me, how do I want them to exist in that space as part of my show?

JF: Do you think this is why, throughout your work, you’re drawn to percussion? In The Fifth Season, for example, there’s more irregular and textured percussive elements.

L: I think so. I’m off the school of “drums first” before any melodic information. Melodic information comes from the voice, so it’s either coming last or it’s coming or it’s not coming. The drums are always first, no matter what the music is. There’s the pulse and something very elemental about that, forcing the body to engage in a way that can’t be intellectualized. No matter how complex the drum pattern is, it doesn’t have to be digestible or something that makes you search for how to move or engage — putting the body at the forefront of the experience right away. With the new music, I want to include a lot of features. I am also interested in new geographies, drawing new maps with people doing things that are disruptive, and not only with their sound but the way they operate in life, how they write lyrics, and who they are in the world. I want to create a sort of geography of new maps with who I think belongs to this family.

JF: Hearing this, I think about the collaborations you’ve had. For example, Midori Takada and the Ceremonial Blue (2019) piece at the Barbican. How did this come about, working with someone who hasn’t released new material for so long?

L: To be honest with you, pure luck. My friends at the time were the creative directors of Kenzo, they had just seen Midori in Paris, and they knew my music very well, and the idea was very much in tune with their thinking. Collaborations, for me, mostly come from the feeling of not recognizing myself in anything. That’s why I do what I do. It’s not to say that these things don’t already exist. I’m not aware of them or I don’t see them because I didn’t grow up with them. Collaborations are a moment of healing and a proposal for a musical family. I didn’t have musical brothers and sisters. I don’t really feel like I grew up with a mom, I didn’t grow up with a dad, and I didn’t have cousins. Thinking about maps or being a descendant of your art might be genre- specific. If you are a rapper and remember the first person that made you want to rap, then there’s a lineage that you’re a part of, depending on where you come from. But I’ve never had that. Collaborations are a way for me to say, “This is my mom.” Maybe you never thought about our music being connected, but it is to me. My collaborations are never based on whether we make the same music. They’re indirect connections.

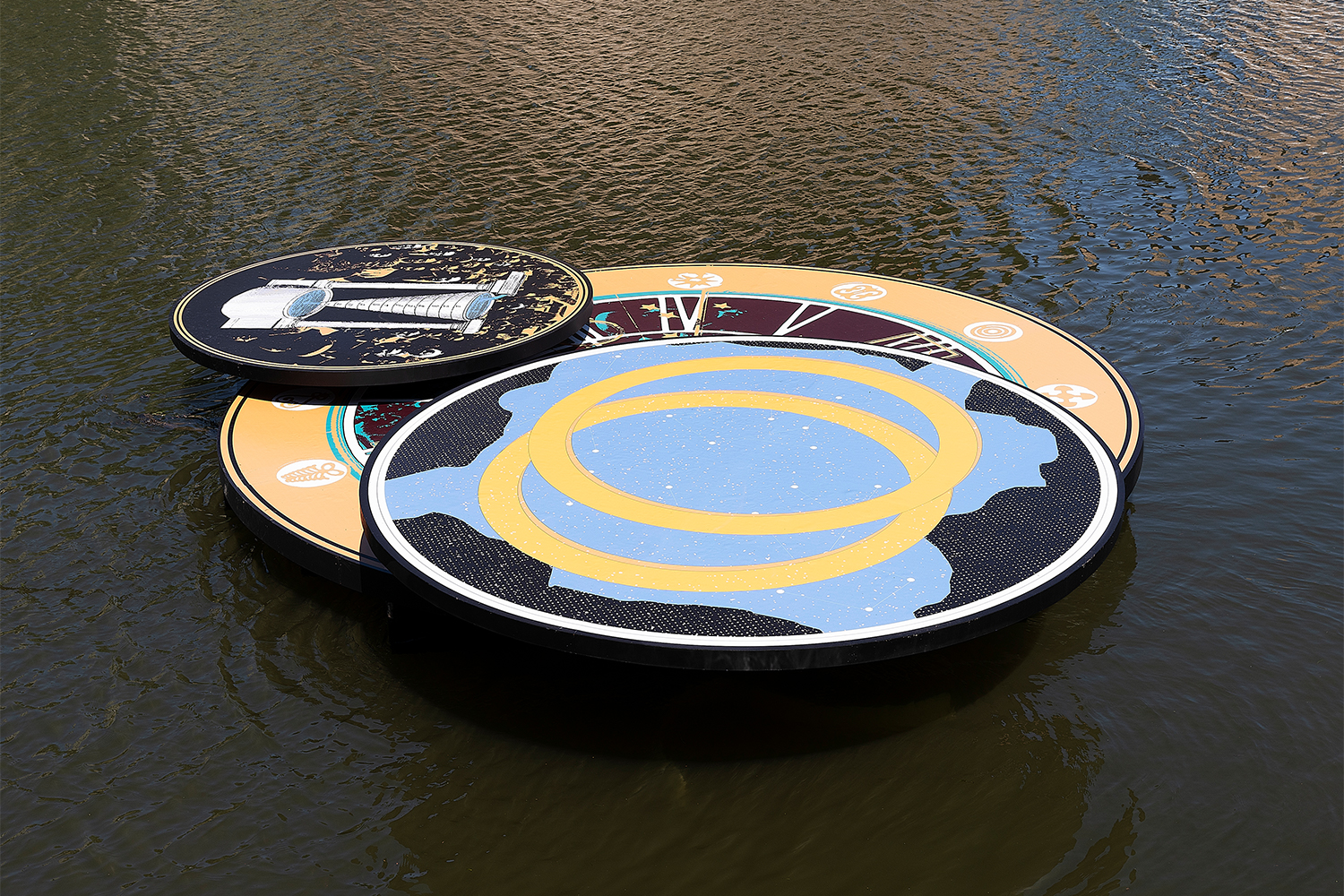

JF: For “Deep See,” the track you made for Laure Prouvost’s film Deep See Blue Surrounding You / Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre (2019), for the French Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, was it a similar approach?

L: No. She wanted to play a game. The game was she wrote a poem with a friend of hers for the film. She gave me and Flavien Berger the same poem and she said, “I’m not showing you the film. I want both of you to put this poem in music.” It’s always fun to have props like that in music: “Let’s play a game.” It means that what you’re going to create comes from another place than what you’re used to, or it just forces things to come from a different place. Still, there was a connection there, because the curator of the French Pavilion, Martha Kirzenbaum, is someone that I am in constant dialogue with.

JF: This relates to the world-building you mentioned earlier, or a cosmology around the artistry of Lafawndah, let’s say. There’s an enigmatic quality to this, but then there’s mapping, threads, and avenues that you follow and leave yourself open to…

L: Well, I also grew up feeling so confined in terms of what I would see were the possibilities. What place are you authorized to imagine yourself in, you know? When people say I’m mysterious, I don’t know what to say about it. I’m not interested in creating any kind of mystique, because that creates distance. I’m hoping that when people use the term “mysterious” it’s because they find the geography unknown or uncomfortable. I’m not trying to hide anything.

JF: Do you think it’s from an impulse of trying to uncover and work through certain fluid parameters that can’t be defined?

L: Yeah. I’ve spent some time in Cairo recently. I’m also connected to North African and sub-Saharan music. The notion of the mosh pit is also translated into so many traditions of trance music and popular riot music in Cairo. All these things exist within me, but I didn’t have access to it; I was cut off from this knowledge because I was living in France. Making new connections between things that are already there but haven’t been uncovered.

Right now there are two things that occupy my time. I like having them side by side. I’m in the most extreme spectrum that I could be in, and I don’t want anything in the middle. I’m writing new music, there is a new record that’s coming, and the music is extreme in the sense that there is, as I said, no middle ground. There is the megaphone and there’s ASMR. I’m making music for insurgency. But then, when you are out in the world, questioning the order of things and going against things, at some point you are tired and you have to come home and be cared for and loved by people around you. Then, on the other side, I’m working on an opera.

JF: You have origins but also what you said earlier — that whirlwind of connections. I love this notion of chaos and moments that can’t be contained. It’s a force.

L: There is an art to the chaotic good. Being intentional and balancing chaotic good is masterful — it is producing something. It’s a force and growth — there is something that comes from it. The opera is called The Descent of Inanna. A few years ago I did a video for my song “Joseph.” On the set we met a mother and daughter, and I wanted to find a reason to spend time with them and tell a story with them. There are different approaches when it comes to storytelling: writing a story and then finding the people; or the people are the point of departure for telling the story and you let the story develop around them.

It was clear that my destiny was to do something with them. But I didn’t want a story about a mother and a daughter, but about sisters, because it’s important to reshuffle.

The Descent of Inanna started drawing itself around my partner and I over the past five years in books and references. This is what it looks like when you open yourself to receiving messages. It becomes clear. The Descent of Inanna is known as the first written story of the origins of humanity from Sumerian Mesopotamia, now known as Syria. Many mythical goddesses since were born out of the figure of Inanna. It’s a supernatural family drama about two sisters who are estranged because one is responsible for the other’s husband’s death. Her sister lives in the Underworld, the Queen of the Dead, while Inanna is living in the world, Queen of Fertility and Change. The story is about implementing a new order, which is what Inanna wants: she is the goddess of fertility, change, and chaotic good. Inanna has memories that she hasn’t lived, of things before her time when gods and humans were living in an anarchist society, more horizontal, with no social order. Inanna exists during a time of shifts in society that feels very close to the one that we know now. Inanna wants to go against those shifts, to use her privilege and her status to prevent them. She meets a dead end because she hasn’t taken responsibility for the death of her brother-in-law nor reconciled with her sister, basically playing herself. It is a story of interior realignment that needs to be made before any sort of seminal change can happen.

I’m working with my partner and this is the biggest project in my life. I get to write, make the music with all my friends, invite actors. A hundred people make up an opera. It is the biggest opportunity for me to create and make apparent another one of those maps that I’m so connected to in my work.

JF: Will you be performing as well as writing the opera?

L: I will not be performing in it. I am composing, directing, and everything else except being on stage. These are the extremes that I am between, I want to be in the trenches, in the mosh pit as a front woman of, like, a riot. Then in the opera house with this piece. I think people sometimes have a hard time believing that about me, that I take equal pleasure in being the front person and being behind the scenes.

JF: That’s a spectrum. Though, right now, theater and experimental music seem even more enmeshed. Where and when will it premiere?

L: It’s going to premiere in Paris. The plan is in 2023. It’s written in French. Although I escaped Paris as soon as I could, I grew up there. In Paris is where a lot of people that I love deeply are making proposals about French culture, so this is very important to me.