“When, beneath the black mask, a human being begins to make himself felt one cannot escape a certain awful wonder as to what kind of human being it is. What one’s imagination makes of other people is dictated, of course, by the Master race laws of one’s own personality and it’s one of the ironies of black-white relations that, by means of what the white man imagines the black man to be, the black man is enabled to know who the white man is.”

These words by James Baldwin, transcribed by Glenn Ligon in his new masterpiece Stranger (Full Text) #1 (2020–21), have a peculiar resonance today, particularly in the context of “post-Black art,” a concept co-invented by Ligon and Thelma Golden in the 1990s around the time of the “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary Art” exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1994. Goldin revisited the concept in 2001, in an attempt to speak about “artists who were adamant about not being labeled ‘black’ artists, though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of blackness.”1

Almost thirty years later, Glenn Ligon’s “Post-Noir” exhibition at Carré d’Art–Musée questions what “Blackness” might encompass in France, where it is “inflected by questions of Algeria, sub-Saharan Africa, and immigration from other places.”2

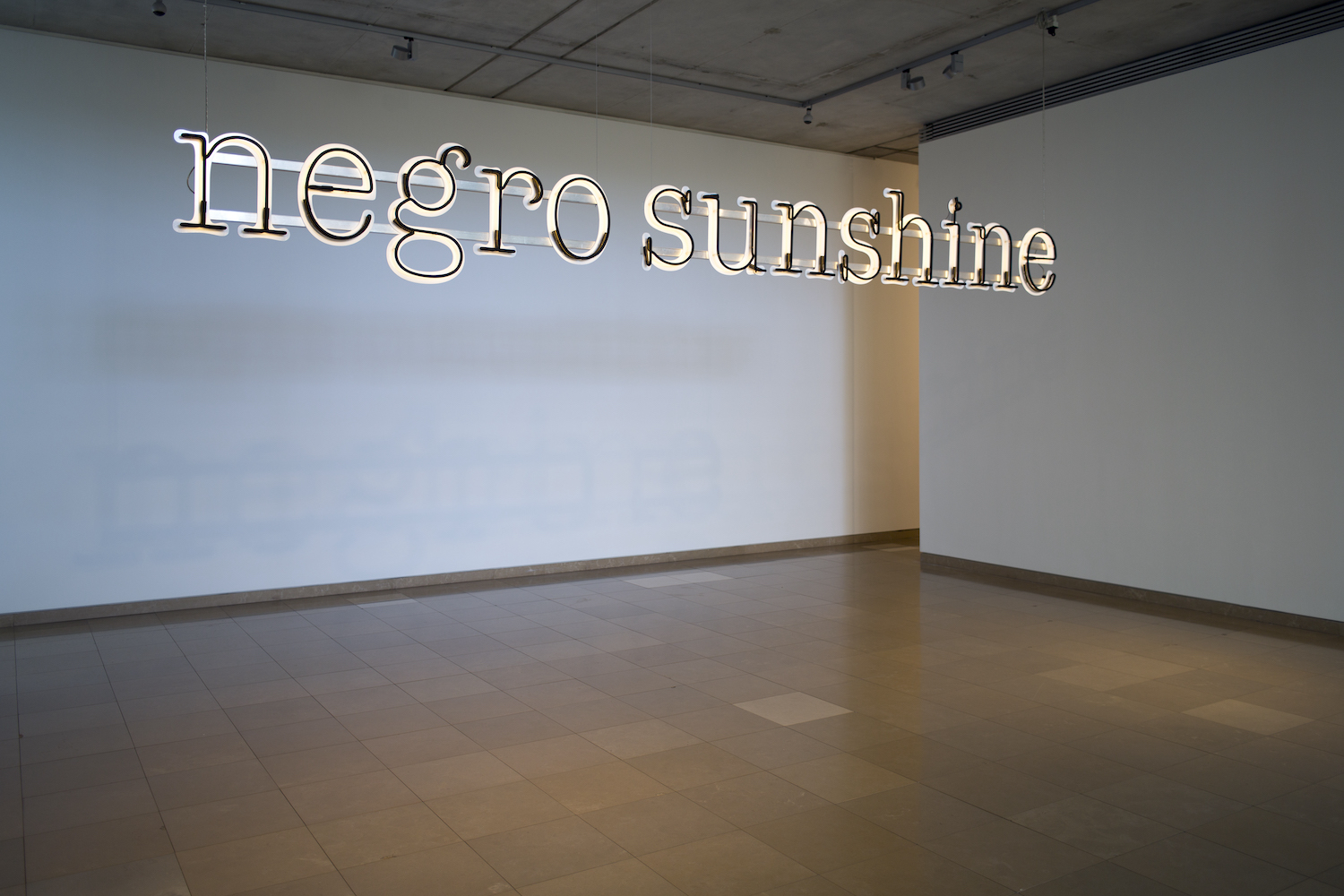

James Baldwin’s essay “Stranger in the Village” (1953) is repurposed as a gateway to the question of Blackness in Europe. If the text has already been excerpted in Ligon’s other works (such as the “James Baldwin” series in the Marciano Collection, Los Angeles), here it is fully rendered onto a large canvas: Stranger (Full Text) #1 is literally what the viewer sees. In keeping with his longtime process of applying black oil stick lettering via stencil, the artist has created a huge painting that is at once a text, an image, and a score. The reader becomes a performer, going back and forth from left to right, enacting the text through movement. Reading becomes a choreography of body and mind. “Stenciling is a way to step back and look at what is left over. In some way it’s related to what I think about text, both the page it’s on and the content. The visual understanding and the intellectual understanding are not separated. The content and the way it looks are very tight for me.”3 Between legibility and illegibility, the process of quoting through painting is “akin to a film adaptation of a text: it’s just one possible way out of many of responding to a given text.”4 The sparkling brightness of coal dust powder, applied to the final layer, reinforces the bedazzling effect of black matter spread beyond the canonical limits of the stencil. Both matte and glossy, the text defies the borders of conventional type, creating a blurring effect. Typos, spots, and stains become new marks. Indeed, in his “Debris Field” series they create a form of abstraction. Here language explodes and parts of letters float across the canvas in an improvised composition. The use of fragments creates new shapes, beyond recognition. Language is used as a found material, like a sculptural object or a film still. A similar editing process can be seen across all the work, from the neon forms of Untitled (America) (2019) to the film The Death of Tom (2008). The imagery in the latter black-and-white 16-mm film is also the result of an error. Ligon reshot the last scene of Thomas Edison’s production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903): Tom’s death. When developed, the film was blurred. Thus content and reading fall apart and engage a new presence: the viewer needs to struggle with the image to receive the text and vice versa. Double America (2012), with its visage reflected across the walls and floors of the museum, is an apt analogue for this struggle between light and opacity.