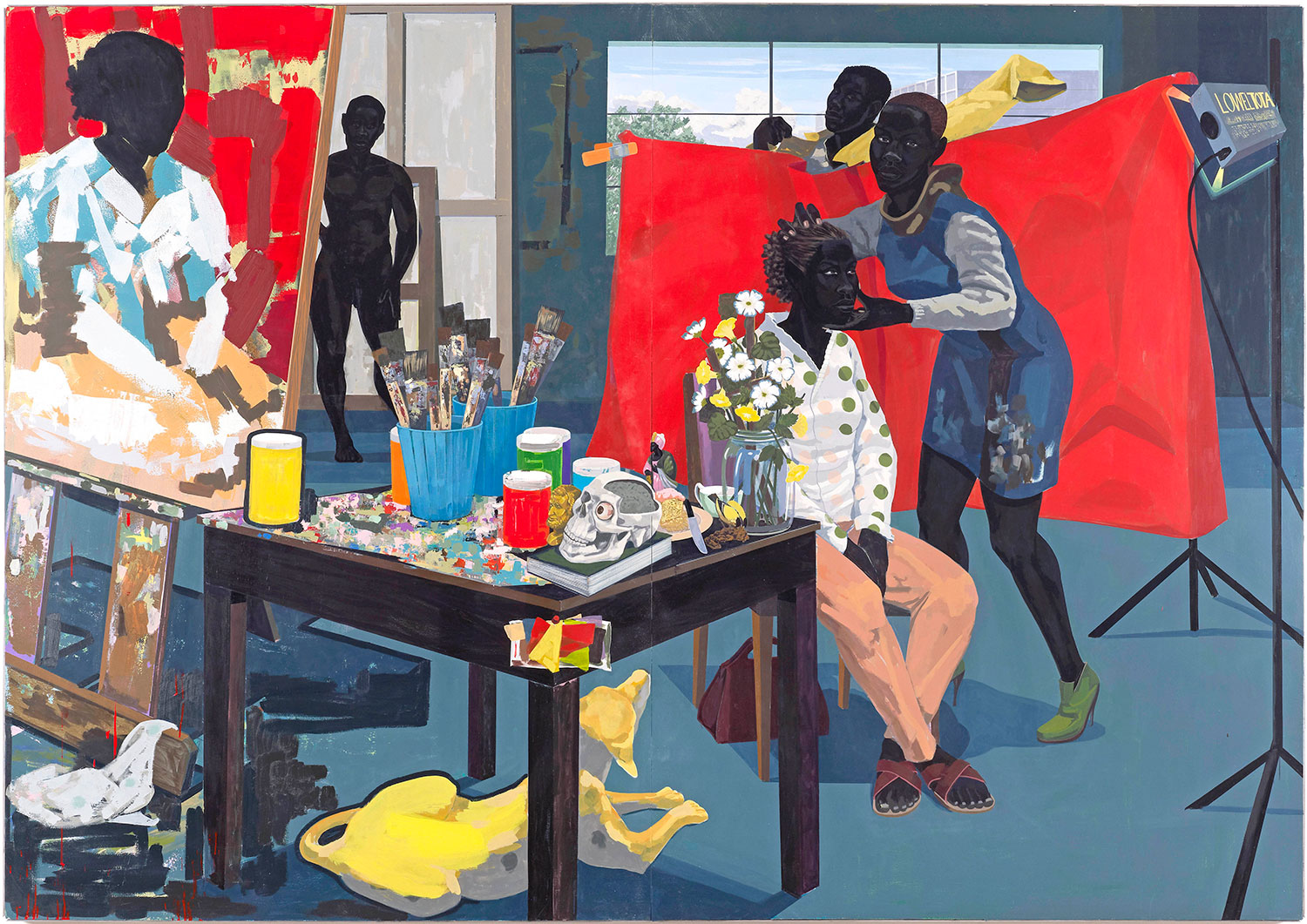

Helen Molesworth in conversation with Kerry James Marshall

Helen Molesworth: You’ve been interviewed a lot, and your biography is very much out there for people. It’s typical, I think, for a story like yours, which dovetails in this extraordinary way with certain cultural events, that that [aspect of the biography] has been repeated a lot. So, I was hoping that maybe we could talk about some other stuff. I thought we could examine a part of your career that isn’t spoken of very often, which is that you were a teacher — what that was like, and what that might have meant for your studio work and for how you thought about art. You taught at the University of Illinois.

Kerry James Marshall: In Chicago. The downtown Circle Campus is what it used to be called.

HM: For how many years?

KJM: I was first hired in 1993, and I think I stayed there for about eleven years before I left.

HM: Does that mean you went through the tenure process? You ended up being a tenured full professor and all that kind of jazz?

KJM: Yeah, I was actually a tenured professor. I went for tenure in the first three years because I got hired under what they call the queue contract. What that exactly means I don’t know, but I didn’t apply for a job at UIC. I started out there as a sabbatical replacement hire for Phyllis Bramson, for one year.

With a queue contract you have to make tenure in three years, because that’s when the review comes up. But, instead of going up for tenure as an associate, they put me up for tenure as a full professor. Literally while the review was going on and my papers were under review was when I got the MacArthur Fellowship.

HM: Oh, I bet that played in your tenure favor.

KJM: Of course there was no way they could say no. In that period, a lot of other things started to happen. I was in a lot of big, high-profile shows. I got lots of recognition, got a number of grants and awards. All that stuff year after year after year started to pile up. And it all just happened to coincide with the time I was having to put my tenure papers together.

HM: What was teaching like for you? What did you think about it? Did you like teaching? Did you see it as a form of community service?

KJM: When I left school, I wanted to prove a point, because I was disappointed with the education I was getting. It wasn’t anywhere near as challenging as I thought it should be.

HM: You mentioned that a little bit in the letter you wrote to younger artists [“Young Artist to Be,” from Letters to a Young Artist, edited by Sarah Andress, Shelly Bancroft, and Peter Nesbett, New York: Darte Publishing, 2006].

KJM: Yeah. Of course my idea of what it meant to go to art school was shaped in part by reading biographies of artists from the renaissance, Vasari’s Lives of the Artists and stuff. There was something about that whole apprenticeship process, and what seemed to be a step-by-step procedure toward complexity. There was discipline associated with the things you needed to know.

That was what I was hoping for when I went to school. That there would be a program laid out where you are required to know, understand and demonstrate your ability to implement different ideas about the ways in which pictures were made and how representation worked, how vision and visuality worked. I thought you were supposed to know all of that stuff, and that it would help you in some way.

In 1977, that’s not how it was. After finishing undergraduate school, it didn’t seem like going for an MFA meant much. So I wanted to prove that you could do all of the things that somebody who got an MFA was supposed to be able to do without having to get one.

One important thing was that you couldn’t really teach at the college level without an MFA. I found a way to get myself into a teaching position by writing proposals for classes I wanted to teach at the community college.

At the time, my teaching philosophy was to provide for my students all the things I thought I should have gotten when I was in school.

HM: What kind of things were those specifically?

KJM: Well, I thought learning was problem solving. On a project-by-project basis you were in school to exercise your aptitude for sophisticated solutions to problems.

I made my students responsible for knowing something about the history of the ways things were done. I set projects where they had to write a proposal before starting a project. You had to explain what your objective was, and then show how you were going to get there. I thought this required more of an intellectual investment in the work if you made it that way.

My ideas about art school were also shaped by an encounter with a graduate student I met after dropping my portfolio off at the Otis College, in Los Angeles, for review. He made me believe I wasn’t going to get into the school because I had done the wrong thing with my portfolio.

Of course that wrong thing was that I had too much variety. I thought I was supposed to show the things I was already able to do. But he told me it wasn’t focused enough on a single idea, and because of that I wasn’t going to get in.

This dilemma of not knowing something that was expected of you that others apparently do know, really shaped my thinking about ambition and what I needed to do. I could no longer accept somebody else’s authority, alone, determining whether I moved on or not. This idea of knowing what you are up to, it really mattered.

HM: When you were asking your students to submit a work plan, what kind of competencies did you think they needed? Did you think they needed to read certain things or look at certain things? Were you sending them to the Art Institute of Chicago? Or were you doing color theory? What were the competencies you felt were really important?

KJM: It was all those things. But, for me, the first level of competency was drawing. Your ability to draw and render what you saw was the foundation. This was not just a mimetic exercise. That skill goes a long way in demonstrating how well you understood the building blocks of imagery. I had my students do lots of preparatory work, and composition was a key component to that.

I always told them that if distortions are in your work, it should be something you decided on, not something that happened because you didn’t know better.

I had them do a kind of schematics. If we were doing a still life, I had them break it down into schematics first and then figure out what the composition was going to be at that stage, and then do a finished drawing after that based on the drawing studies you made, not just on what you were looking at.

I used the Art Institute, and I used reproductions that were clipped from art-history books and things like that. Style was a choice. I taught a painting class where the entire semester was all self-portraits. Everybody did a self-portrait and then every self-portrait after that had to be different from the one you did the first time. You chose different styles because you needed to know why that would be a better choice than another mode you could select.

That’s the way I thought education was supposed to go. Then, you were equipped now to do anything you wanted to do.

HM: You said at the beginning though that you felt ambivalent about teaching. Where did that ambivalence come from? What was the part of it that caused you to have second thoughts, so to speak?

KJM: Teaching eats up a lot of energy. If you are really doing what I think needs to be done, which is constantly challenging the students’ ability to do a thing and building up a repertoire of technical capabilities and understanding, that’s what it takes, and that is a lot of work.

It eats into your ability to do your own work. There was always this thing where I had said to myself: “I didn’t get into making art because I wanted to be the best art teacher I could be. I got in because I wanted to become the best artist I could be.” At some point, you have to be able to give all of your energy over to just simply making the work, because if you keep having to divide your energy and your attention between teaching, then there is a way in which it compromises what you do.

Then there is something about being in the academy that in time begins to change your tastes to fit into the academic mold. So then everything starts to become the same kind of thing. That was something that I didn’t like. You can lose your sense of judgment about the value of things because you have to talk about everything as if it is equally important.

Those were some of the dangers I felt being in the academy. The other part of it was that I had so few opportunities to work with black students, because there were so few black students in those programs. It just felt like you were constantly reinforcing the same privileged access that white students already had to the best kind of education. It was nearly impossible to cultivate a large enough class of black students or Mexican students or Korean students who might want to do work that might be different.

A competitive capacity has to be encouraged where people of color are revved up to challenge the dominant white majority in the art world. Not just hoping they are welcomed into the mainstream, but to really go after a place in the art world because your pursuits are truly transformative. I mean, it’s the same kind of pursuit that leads to the Nobel Prize or to the standing of artists like Donald Judd or Jackson Pollock or Andy Warhol. They are the artists whose productivity shaped the conversation about what kinds of things are possible in making art.

I think you need an army of people who are aimed at doing that. It’s challenging when there are so few artists of color in programs so you don’t really get a chance to do that with them, but you constantly have to keep doing it with students who already have access to that kind of experience.

HM: Why do you think in Chicago, at the sort of flagship city college, you weren’t able to garner students of color to the art program? Chicago is a very diverse city. And you are talking about the public university. Where was the gap there?

KJM: Well, there are two ways that has to be understood I think. One is that within the visual art world, you’re still going up against this idea that you are not likely to be able to make a living with a degree in the arts. For people of color, going to school for four or five years and being able to make a living matters. You will find more people of color going into art education.

HM: Right, that’s sort of a professionalized way to be in the art world.

KJM: There is a program, a course of action, and then a job at the end of the line. It was more likely that — when they had an art therapy program, you would find more people of color in the art therapy program for the same reasons. Because there was a payoff at the end. But in fine arts, you are on your own. To the degree that most people don’t consider undertaking this path. When ideas about what’s relevant in fine art, let’s put it like that, are articulated, they sound like nonsense to a lot of people. I mean, you are not going to get a lot of people signing up for that, people who are already, in some ways, barely making it to the school in the first place. That’s one thing.

The other side of it is that there not only were few students of color coming into the program, but I was the only black faculty in the art program. That matters too, because when the selection process for reviewing students for graduate school and stuff comes in, of course the sensibility of the faculty determines who gets in and who’s not in. They will keep reproducing the things that they are interested in. That’s just the way it goes. I mean all the things that remind them of themselves when they were at that stage are appealing.

That’s the other part of it. I only had one vote, and I’ve heard more than a few times: you cannot put together classes based on what people’s ethnicity and race is. Then it becomes that quality thing. Part of what happens with universities is they seem to all be choosing students that are already doing the kinds of stuff that you saw in the gallery yesterday.