Who better to interrogate the inherited habits of modernism, in so far as they continue to shape painting, than Oscar Murillo (b. 1986, La Paila, Colombia), an artist whose meteoric success has engendered a self-conscious scrutiny of his own creative processes and methods of display? Murillo’s currency as an artist has a great deal to do with how he productively metabolized outsized expectations into a rigorous examination of painting’s horizons, looking both backward and forward, inward and outward.

One modernist shibboleth, the artist’s studio, was long mythologized as the hallowed refuge for the individual artist. We know better now, thanks to artists who set forth and pioneered more collective models of production and address. Lone makers became traveling bandleaders and talent scouts, diversifying their output and drawing out the potential of a host of collaborators. In the process, they attempted with varying degrees of success to bridge the gap between art and life, and to maintain individual creative freedom, while keeping lines of communication open with the rest of society, including those not traditionally granted access to works of art. Murillo has kept one foot at least firmly planted in his studio; painting, albeit in a hybrid form, remains central to his activity. His work reveals a sustained commitment to scale, color, gesture, texture, and, in some cases, heavy impasto and energetic brushstrokes reveling in the viscosity of paint — all hallmarks of a heroic tradition of abstract painting.

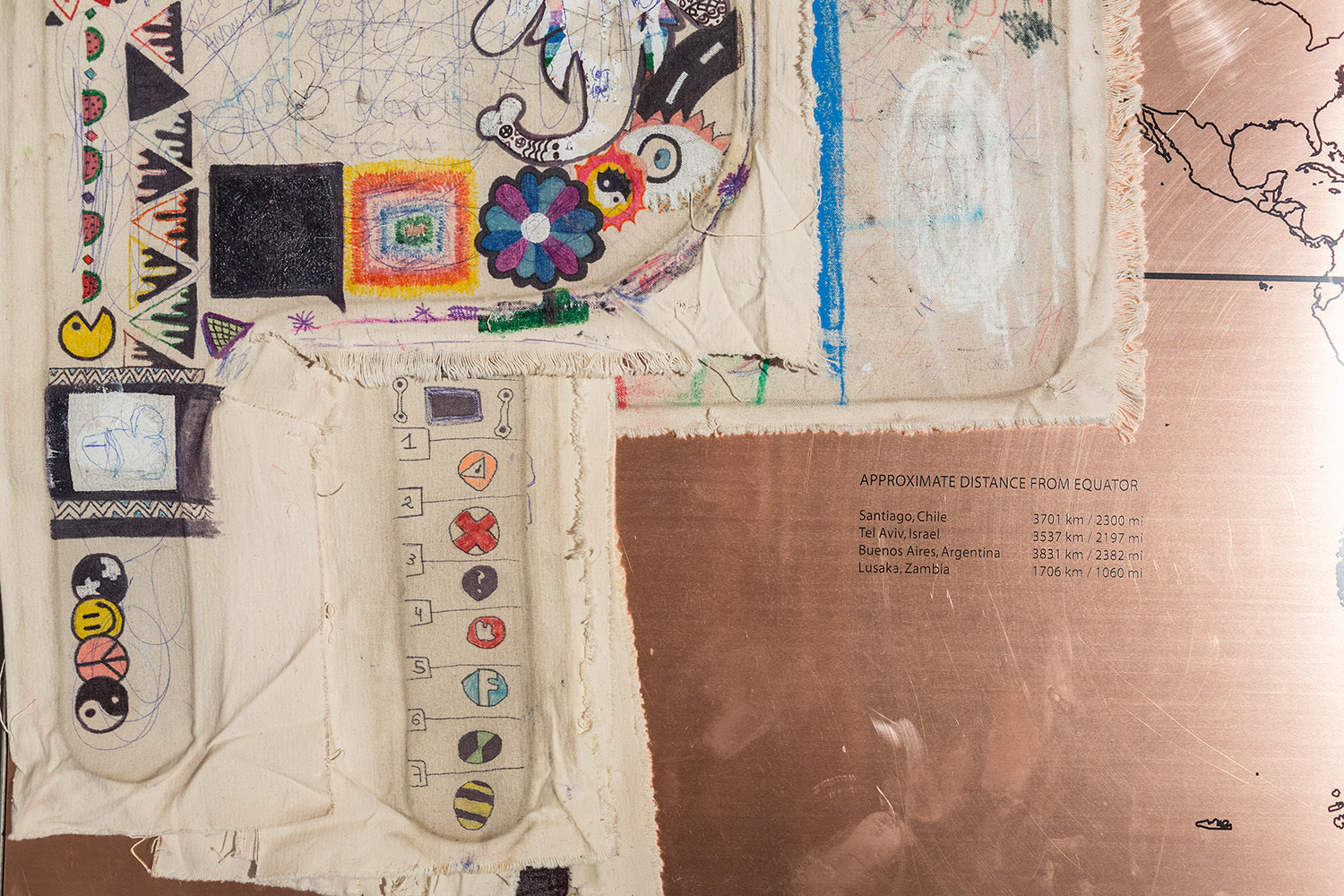

For that reason, it is has been pointed out that in Murillo’s work there is a “tension between wanting to make statements about the wrongs of the world and experimenting with the formal boundaries of his art.”1 To which he has responded: “It’s the tension that keeps it alive.” Indeed, even as he ranges farther and farther afield, from South Korea to Azerbaijan, and engages legions of schoolchildren in thirty-one countries through his project “Frequencies,” Murillo continues to make paintings in his studio. Put another way, his globe-trotting explorations of solidarity, cultural exchange, displacement, and the fallout from globalization in a variety of initiatives, many of them community-based collaborations, reaffirm rather than undermine his commitment to painting in his studio.

Okwui Enwezor, who invited Murillo to participate in the 2015 Venice Biennale, underlined the artist’s interest in the “porous border between studio and the real world.”2 Performative installations, such as A Mercantile Novel, created at David Zwirner in New York in 2014, in which he recreated a factory assembly line, as well as the incorporation of sediment, text, and studio scraps in his canvases, embrace audiences outside the traditional artistic sphere. He associates the words scrawled on his paintings with foodstuffs identified with underprivileged segments of society. “Solidarity” refers to reconstructing the complicity between artist and viewer, a common ground for overcoming or mediating social, economic, and national differences. This issue was at the heart of the 2019 Turner Prize when Murillo and his fellow finalists, all of whom are “engaged in forms of social or participatory practice,” asked to share the award, a statement of “community and solidarity” and an expression of their “artistic efforts to show a world ‘entangled.’”3

Murillo’s reification of painting in a wider field is perhaps best appreciated through the ways in which he exhibits his work. In complex displays, wooden structures resembling actual scaffolding provide various forms of support for his paintings. He also piles them on the floor, drapes them like laundry on clotheslines, and hangs them from trees. In “The Forever Now,” an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 2014, visitors were encouraged to handle several of Murillo’s canvases left on the ground “like rugs at a bazaar,” unfolding and refolding them to explore their texture and composition.4 But the same paintings were also framed conventionally and affixed to the wall. In taking painting down a peg, so to speak, by allowing direct, tactile interaction with the unstretched works, Murillo reoriented its address but reconfirmed its status.

Similarly, in recent projects such as “Horizontal Darkness in Search of Solidarity,” Murillo’s elaborate environments peopled by effigies encourage viewers to become part of the work, “to sit down and look at paintings.”5 There, as in many of his projects, effigies — based in part on muñecos, figures burned in Central America at the New Year — act as répoussoir figures, inviting us in, creating a viewing position, and indicating what we should look at. In this context, painting is part of an everyday world while remaining authoritative and self-sufficient.

“The Forever Now” was predicated upon atemporailty, the notion the “all eras exist at once.” The exhibition suggested that Murillo, in crafting works in his studio cobbled together from remnants, roughly sewing them together and imprinting motifs from one work to another, created a closed system based on “self-cannibalism.”6 Be that as it may, Murillo’s “sampling” draws upon a variety of sources beyond the physical ingredients within the artist’s reach. This engagement of modernist methods and materials, many of them historically defined, suggests that dialectics fuel his work as much, if not more than, simultaneity.

Murillo frequently evokes aspects of works by postwar modernists on both sides of the Atlantic. Even his recourse to bits of cast-off canvas and the irregular stitching binding them together recall trademarks of the work of Italian artist Alberto Burri.7 In Signaling devices in now bastard territory (2015), the work he contributed to Enwezor’s Biennale, Murillo hung twenty oversized black flags from the portico of the Giardini’s central pavilion. He burned the paint into the fabric with an iron to give it the texture of roughed-up skin. The treatment of canvas or other fabrics as flesh and the use of burning as a strategy are both reminiscent of the boundary-pushing techniques pioneered by Burri. Trained as a doctor, Burri used abraded, sewn-together, cast-off burlap bags in his Sacchi (sacks), in which the stitches suggest those of a sutured wound. Burri also used other unconventional materials as both support and media, including tar, mold, and, in his Combustioni, wood laminates and plastic, which he torched to produce charred, unpredictable results. The sacks themselves have been compared to the burlap bags used to transport supplies in postwar relief efforts. Conceived during after the global trauma of World War II, another period of dramatic migratory shifts and contrasts between have and have-nots, Burri’s work offers a useful template for Murillo’s exploration of those themes today without requiring him to renounce his formal concerns.

Regarding the painted motifs on many of his canvases, Murillo has said “a lot of this mark-making is a release of anxiety and physical energy.”8 The sheer force of his expressionist gestures also suggests manual labor, the honest work done by paid laborers, as opposed to the speculative tinkering of the artist in the studio. Here Murillo is restoring to the individual gesture the potential political charge that midcentury American critics worked so hard to deny, as they made artists apolitical and converted Abstract Expressionism into a realm of pure aesthetics. Still, the dialectics driving the existential strain of action painting underpin even Murillo’s purportedly atemporal maneuvers. This is clear in his description of Catalyst (2019), a work he created by placing an unstretched painted canvas on the floor, painted side down, on top of another one, and pressing on the back of the top canvas with a stick so that the impression of his marks is left on both. “I call it Catalyst,” he says, “because it is about action, and reaction.”9

Murillo has expressed admiration for the Neo-concrete movement in Brazil, whose artists “were able to appropriate this stiff, rigid period of European modernism and digest it. […] And they opened it up and made it accessible to society.”10 In a similar spirit, the elaborate scaffolding for several of his more recent exhibitions embodies Murillo’s elaboration of a utopian vision unifying art and life. Those frameworks, fostering “solidarity,” activate, too, the infrastructure of De Stijl’s proposed marriage of art, architecture, and modern life, as laid out in the prophetic writings of Theo van Doesburg and paintings by Piet Mondrian. Stijl — post, jamb, support — refers to the construction of crossing joints, most commonly seen in the kind of carpentry used in Murillo’s skeletal two-by-four constructions.

Mondrian painted compositions in which squares or rectangles of pure colors were suspended from and framed by a matrix of vertical and horizontal lines. Intentionally or not, Murillo’s constructions, which translate De Stijl’s grids into three-dimensional viewing spaces, as well as his notion of a collective project, recall their efforts to create a universal experiential language without forsaking formal concerns.

The tension between inside and outside, individual and collective, in Murillo’s work brings to mind one of the watersheds in recent art history. Philip Guston, explaining the factors goading him to abandon abstraction, which had come to represent his isolation from increasingly urgent everyday concerns, revealed: “So when the 1960s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything — and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”11 To be sure, Guston didn’t climb the barricades; he continued to paint, looking to his own previous work, cannibalizing it, often quoting his earlier iconography in paintings based on shared, if imperiled, humanist values. For this reason, Robert Sifkin has identified in Guston’s late work a romantic strain of postmodernism he describes as the “tension between acknowledging the exhaustion of the humanistic tradition and its hallowed forms of articulation and the intransigent desire to continue working in that tradition.”12 Regarding his painting Violent Amnesia (2014–18), which lent its title to an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard in 2019, Murillo spoke of the “balance in [his] work between my desire to think primarily about image making, texture, form and so on, and this constant awareness of the world.”13 While he looks farther afield, and to a more diverse audience, Murillo’s “sampling” is just as self-reflexive and just as invested in the status of painting as Guston’s.

When Murillo explains that the title of his exhibition “Violent Amnesia” “is also about knowing that what I want to express can never be fully realized, can never be fully imagined,” he echoed a refrain intoned by many artists, not least Mondrian and Guston.14 Mondrian’s ultimate goal, according to many critics, was to eliminate “the tragic”; in other words, he was driven by the imperative of art to establish legible and ordered systems of forms. Guston returned to this theme of “the tragic” in relation to Mondrian over and over again. Contrary to those who privileged “self-expressionism,” Guston, in speaking for himself, sought what he called an “optimum order,” in which the artist “eliminates himself in some way.”15 In this quest, he believed that Piero della Francesca and Mondrian perhaps came closest. But if Mondrian sought clear systems to eliminate the tragic, to Guston it was the search itself that was tragic because it was destined to failure.

Yes. But I was just now going to say that the quest for this optimum order, as I call it, which is beyond tragic or the humanly tragic, fascinates me. More than fascinates me, involves me very much because it’s the quest itself, which is the tragic thing because it can’t be achieved, in essence. I think what I have in mind is that it’s inevitable that failure is the only quality which ensures continuity of creation.16

–– Philip Guston

Murillo keeps things alive precisely because he remains alert to the risk of failure, but also to its dialectical potential.