Using commercial objects and ideas Pamela Rosenkranz (b. 1979, Switzerland; lives in Zurich and Bern) explores a halo of emptiness that presses like air against the human race. Slick and precise, she has assimilated the work of the Southern California Light and Space movement, as well as the predigested conceits of the Minimal Conceptualists that helped define the art of her youth. Seemingly seeking a reduction to nothingness for both herself as an artist and her work, yet maintaining a strong visual vocabulary, she is like a subatomic particle that must be defined by what it is not. Her practice can be penetrated via its opposition to the subjectivism that became integral to art during the latter half of the twentieth century. Through a questioning and emptying of both meaning and form, she challenges the abilities of earlier generations to embed emotion and plot into objects and ideas. Now, fleeting moments are shown as empty and shallow, rather than full and beautiful, and the temporary experiences and fragility of human life are seen as something not to find energy within, but as statements of our biological weaknesses. Her deconstruction of the romanticism of art is also her assault against the romanticism of life. By questioning art’s affair with illusory subjectivity, Rosenkranz hits us at the center of our most guarded superiority: culture. She chips away from there.

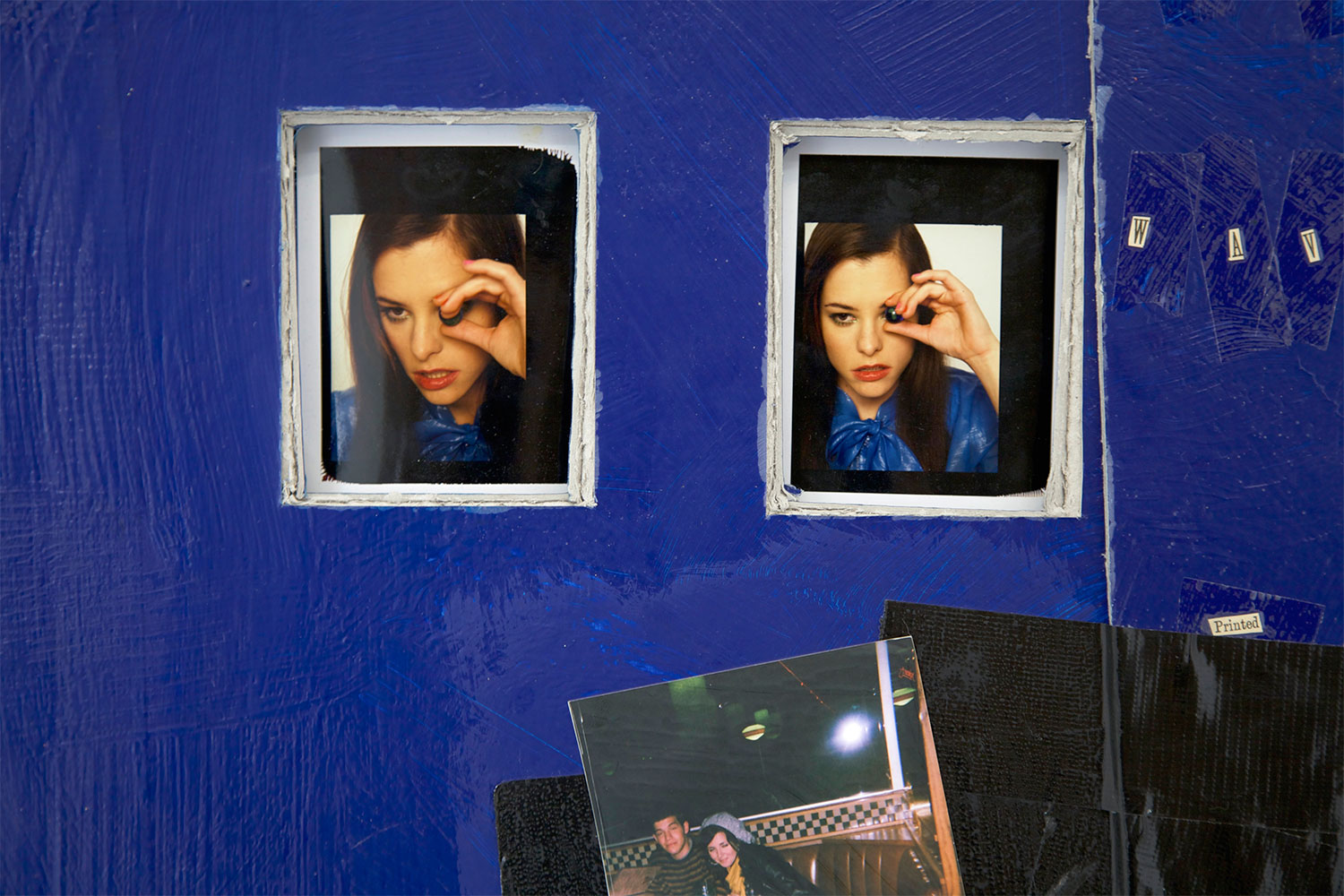

This assault is most overt in a series of works dealing with Nouveau réalisme artist Yves Klein. Death of Yves Klein (2011) is a single-channel video of unmoving cerulean blue hung as a painting. Roughly simulating the hallmark International Klein Blue, which Klein chose because he felt it captured endless space, her video contains an audio overlay that lists the chemicals that many believe led to Klein’s death at the age of 34. Both a sly, dehumanizing, reference to the infamous Windows system software “blue screen of death” and a shrewd art-historical reference, the piece equates the chasing of artistic legend with suicide, and it uses standard technology — the light emitted by a television — to evoke a supposed cultural masterpiece.

The series Because they tried to bore holes in my greatest and most beautiful work (2011–12) takes images of Klein’s blue monochromes (1956–62) from the Internet and blows them up to human scale. Problems of digital representation and translation pair with an imperfect mounting process that scars the resulting prints. Rosenkranz draws upon the physical nature of things to take revenge upon the idea of the visually transcendent. These pieces, much like her video, show the monochrome as an empty though visually appealing tone on which we invest feelings of divinity and grace.

Rosenkranz’s series of acrylic on gold and silver emergency blankets, Stretch Nothing (2009) and Express Nothing (2011), are another example. Skin tone markings made with sliding hands and arms appear energetic yet controlled. The works reference not only Klein’s appropriation of the body in his Anthropometries (1959–62), painted by pressing or dragging a painted female body, but more directly Janine Antoni’s Loving Care (1992). This performance and resulting installation, done a number of times in the early to mid-1990s, saw Antoni paint exhibition space floors by dipping her hair in a bucket of Loving Care hair dye and slowly painting herself and the audience out of the space. As with Rosenkranz’s pieces, the final form is physical without being literal. Rosenkranz has long been interested in the commercial names of colors, and she often includes them in the titles of her works: “Creamy Brown,” “Fresh Ebony” and “Milky Stay” are a few fleshy examples. This is also true of Antoni’s performances. The hair dye color is “Natural Black”; as a branded item derived from an organic order, it is an important part of the artwork’s labeling. But when Rosenkranz makes a reference to the body it is one of true absence. In Antoni’s performance, her personal body became a public material, and the hair dye related to her mother. Rosenkranz refuses to grant any personal privilege or backstory in her explorations. One of her most impressive abilities is to make herself disappear within a process-based and corporal art.

For an idea of how nonorganic Rosenkranz’s work is, compare it to Klein’s first experiments using the human form as a paintbrush. In 1958 he experimented with menstrual and ox blood, but the resulting works were destroyed after they caused Klein nightmares. Rosenkranz, in her circling of the body, prefers the completely synthetic, refusing to deal with the physical body even as she does so. Hers is a belief in the plastic over the organic — that the truth lies in these empty fabrications. When she visually refers to skin, she refers not to the skin of human mammals but to the skin of Barbie and high-end sex dolls. Always hairless and flawless, they are empty surfaces that suggest a whole. This is the complexion of well-lit porn, aspirational for a first world that is constantly plasticizing its popular views of the body.

Rosenkranz crafts works about humanity with the air of someone who is not human. Imagine the disposition toward humans spouted by popular representations of superior humanoids (X-Men’s Magneto, for example) and you’ll find this mimicked subtly in her work. Exemplary of this is Bow Human (2009–12), a series of sculptures featuring crouched human shapes covered tightly with gold emergency blankets. They are slick updates of Antoni’s Saddle (2000), an empty human form on hands and knees crafted from translucent golden rawhide. Rosenkranz’s cold, severe and reflective sculptures show the figure in its most cowering state. Where Antoni finds beauty in the wildness and fragility of the human form, Rosenkranz shows detachment at best. Her title may read as a command —“Bow, human!” — a statement echoed throughout science fiction by dominant alien beings.

The initial striking beauty of these works comes mainly from the emergency blanket, a thin plastic sheet developed by NASA in the 1960s that conserves 97% of the body’s radiated heat. This artificial covering protects the human body from one of its many vulnerabilities while being almost materially perfect itself. Thus Rosenkranz presents a cheaper, simpler and stronger stand-in for gold. They are the opposite of Roni Horn’s Gold Field (1980–82), a hundredth-of-a-millimeter-thick solid sheet of annealed gold that tenuously hovers on the floor. It was created because Horn “wanted a closer relationship with the sun.” Rosenkranz’s gold blankets correlate with an interest in the sun as well, but as a symbol for a coreless center. Both the paintings and the sculptures were first shown in her exhibition “Our Sun,” in 2009, at the Istituto Svizzero di Roma’s Venice location. Tellingly, she opened the press release with a quote from the philosopher Reza Negarestani: “For after all, the Sun is only an inevitable blind spot for the Earth that bars the scope of the abyss.”

That exhibition was also the first to include Firm Being (2009–14), a series of acrylic-and-polyurethane-filled PET water bottles with their branded labels intact. They congregate in corners on the floor, are packed together in glass-front display refrigerators or are sometimes alone in vitrines. The seal is broken on each, and they are usually full of different approximations of the range of human skin color. They’re figures with no personality, an empty whole, human beings as branded containers. They form a strange opposition to the masses of individually wrapped candy that Felix Gonzalez-Torres made between 1990 and 1993, particularly Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991). Here, the designated amount of multicolored candies corresponds to the ideal weight of the artist’s dead lover. By letting viewers freely take pieces of candy, thus letting the physical form of the work ebb and flow, González-Torres wanted to create a living allegory for eternal life. Rosenkranz’s solid entities refuse that. While they relate to the body in a similarly indirect way, they are never concerned with death because they are never concerned with life.

Water or something related to it flows throughout Rosenkranz’s work. In addition to the bottles there have been pools (skin toned, Skin Pool, 2014, or blue, Clean Eyes, 2014), running sinks (More Stream, 2012) and video projections (Loop Revolution, 2009). Water is a transparent, visually barren substance that the human race has endlessly contemplated. Rosenkranz choses it not because it reflects purity but because, like plastic, it projects nothingness. This has been illustrated with works like Firm Being (Content Water) (2010) in which she filled Fiji-brand water bottles with clear polyurethane, using the artificial to perfectly imitate the purely organic. The marketing of water and other lifestyle brands is central to her practice. Titles of exhibitions and works have borrowed slogans as statements of fact: “The Most Important Body of Water is Yours” (Evian) and “Untouched by Man” (Fiji), for example. Other times she seems to create her own slogans: “Nothing Unbound,” “As One,” “The Wild Blue Me,” “My Evolution.”

You Are the Weather could easily be one of these. Roni Horn’s first photographic installation (1994–96) consists of one hundred images of a girl’s face rising out of Icelandic geothermal pools. All water and skin, only slight differences of expression and atmosphere are betrayed. The confrontational work exhibits a broad range of emotions — those of the photographer, the water and the girl. A confluence of the same subjects is seen in a series of large-scale inkjet prints Rosenkranz soaked in Smart Water and then let dry before framing. Meaning Metaphores (2012) uses a stock image of a child’s face with a world map overlaid on it to question the notion that the human body is similar to the Earth’s bodies of water. While Horn shows the changing nature of both the human face and water (as steam, as cloud, as liquid), Rosenkranz diminishes the idea to a meaningless level of internet-ready randomness. It reduces the human to the level of water, exposing an unspoken truth: the water in different branded bottles is pretty much the same, and so are we.

That many of the ideas and tropes fundamental to Rosenkranz’s practice had their genesis in her 2009 Venice show comes as no surprise. The city has inspired artists for centuries. And yet, much in the same way that she doesn’t deal with lived experience, her work never traced the romantic idea of the wet, decaying city. Venice, like the work of Antoni, Gonzalez-Torres, Horn and Klein, has at its cultural core a magnetism for the subjective nature of human thought. Rosenkranz, however, cuts through these entrenched societal feelings and looks for objective truth.

With “My Sexuality,” an installation at Zurich’s Karma International in June 2014, Rosenkranz expanded her practice from sight and sound to the element of smell. Synthetic cat pheromones, which also affect humans, wafted through the plastic-draped gallery, where six projectors shone blue and pink on aluminum panels dripped and spread with acrylic. The paintings, Sexual Power (Viagra Paintings, 1–11) (2014), are vulgar and visceral, using fleshy tones that expose inner beauty in the literal manner of Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer. It was a clear transition for Rosenkranz’s practice, discarding the commercial for the self-created, referencing the self the way mirrors do.

Her interest in addressing other human senses is at its beginning. Having returned to Venice to represent Switzerland at the Venice Biennale, Rosenkranz now seeks to silently attack all of the senses at once. In the air of nothingness that surrounds her themes, it is important to remember Gonzalez-Torres’s central piece when he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2007: two circular reflecting pools that touch just enough that their water is shared, Untitled (1992–95). In Venice, Rosenkranz’s body of water is solitary and encompassing, seemingly holding to itself while affecting every viewer that enters the space. Rosenkranz knows that we do more than drink water. We see it bottled, puddled or wild in the ocean, but also breathe it in and feel it against and within our skin at all times. It is close to nothing, but for us it is everything. Rosenkranz’s explorations are the same; in her reduction to emptiness she achieves a monumental depth.