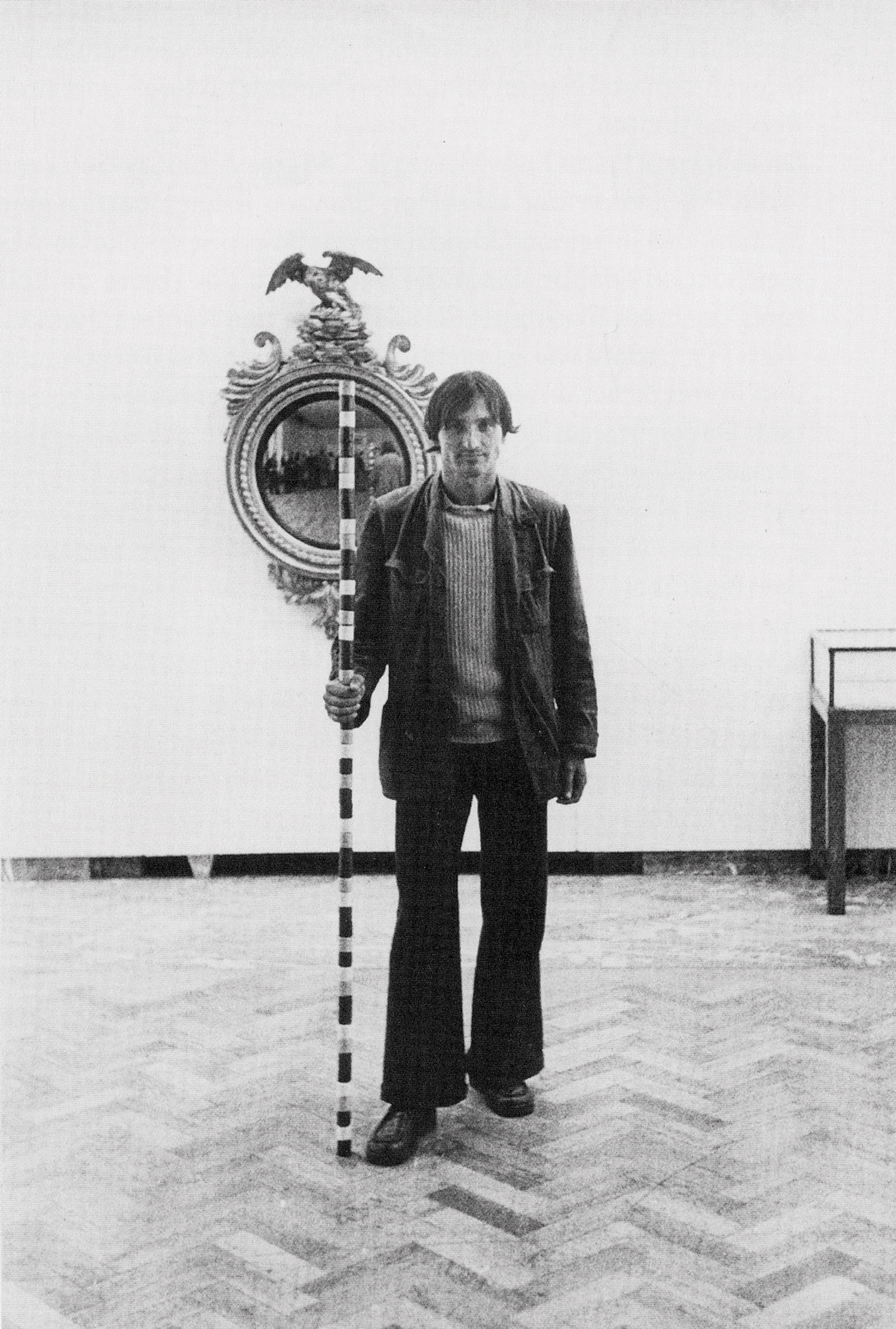

The exhibition “Katarzyna Kobro/ Lygia Clark” activated the new building of one of the oldest museums of modern art, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. Its collection was initiated by a group of artists, among which is Katarzyna Kobro — a sculptor, a painter and an art theoretician considered to be one of the most outstanding representatives of the Polish and international constructivist avant-garde. However, conceivably the world’s most famous South American neo-avant-garde artist Lygia Clark couldn’t possibly have known Kobro’s output. Nonetheless, their artistic activities obviously met on several planes. The exhibition aimed to underline the comparable and contrasting reflections by these two artists on relations between body and space, and how they define each other.

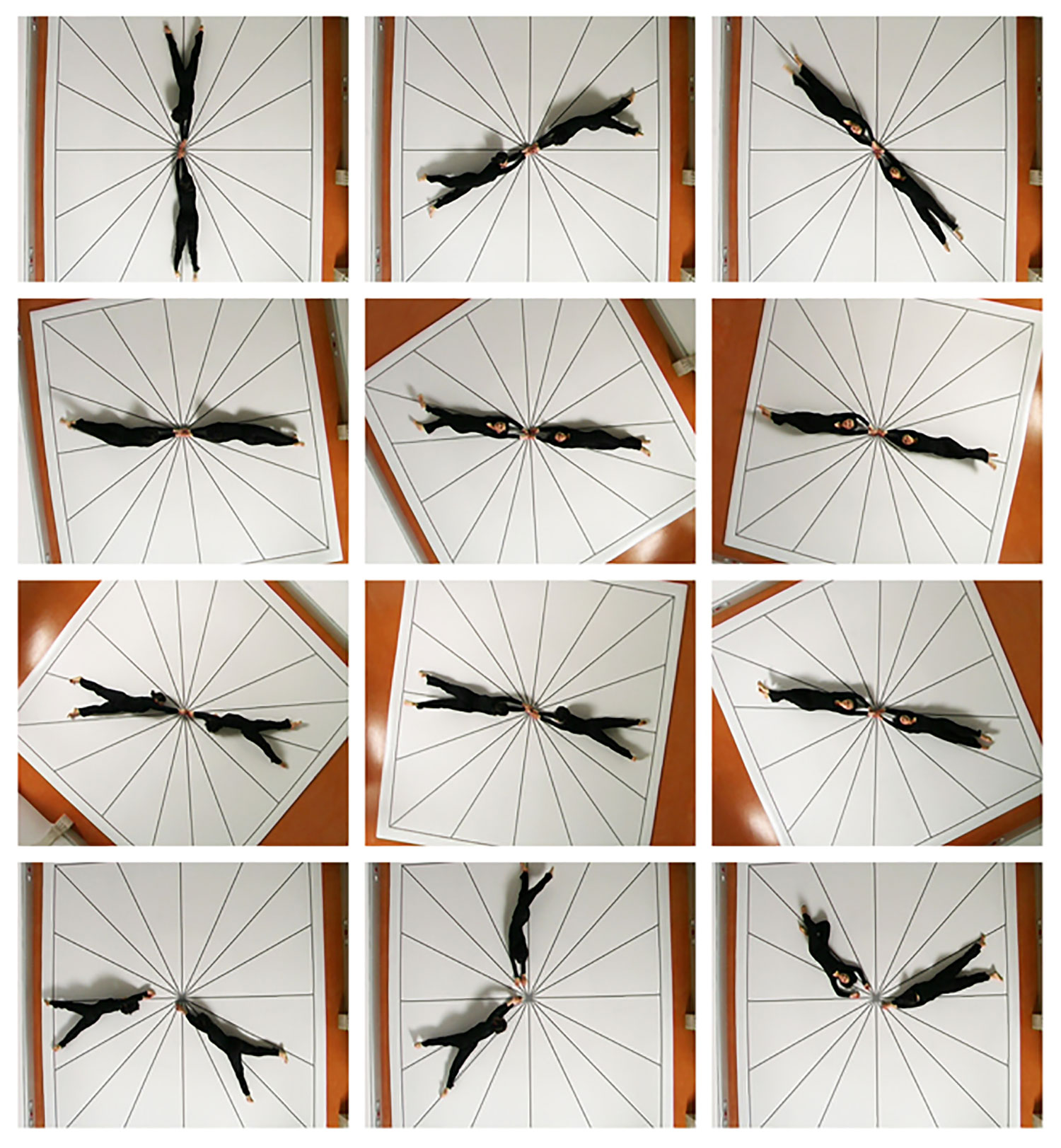

At the starting point of this artistic discussion were Kobro’s Spatial Sculptures, Spatial Compositions, Abstract Compositions, Hanging Constructions and Project of a Functional Kindergarten from the ’20s and ’30s, which represented her vision of connection and unity between space and sculpture. For the Polish artist, sculpture became the most condensed part of the space and referred to the relation of the body movement within the space, its rhythm of measures and divisions. The core of Kobro’s output was here confronted with Clark’s early works, like Casulos (Cocoons, 1958) and the series of flexible sculptures entitled “Bichos” (Animals, 1960). However, while Kobro’s output presented ideal sculpture as an open space, Clark was concerned with “the death of the plane.” Thus “Bichos” were thought of as “living organisms”; the mobile body of their structure allowed them to abandon the two-dimensional plane and transform into a kind of a spatialization of space. Contrary to Kobro’s objects, Clark’s work required human energy, touch and interaction.

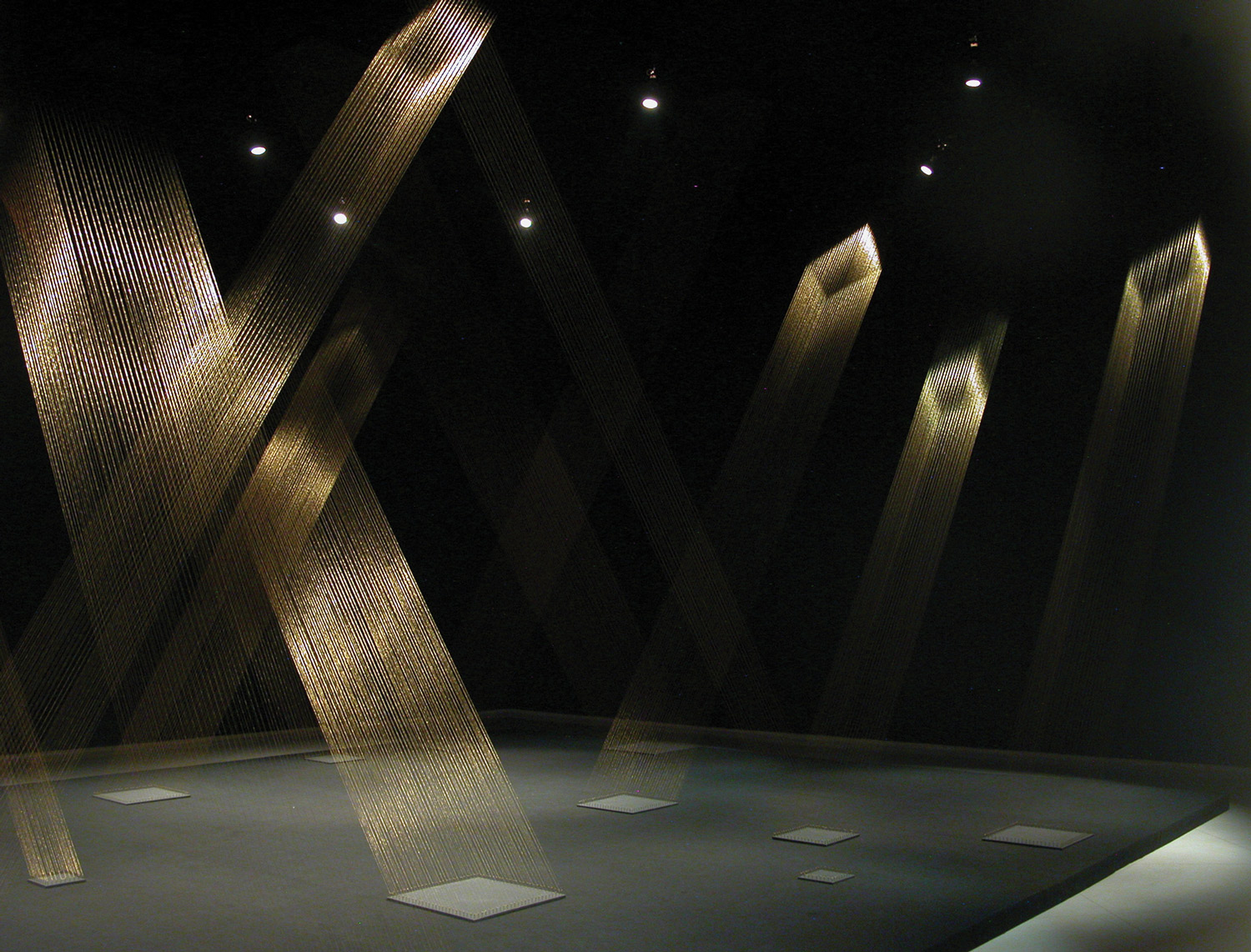

While the first part of the exhibition focused on Kobro’s and Clark’s creation of objects, the second part demonstrated Lygia Clark’s focus on artistic action. A casa é o corpo (The House Is The Body, 1968) was a tunnel-installation constructed as a passageway, which prevented the person walking through it to move freely. Clark’s aim was to introduce the unfolding sense of primal touch by creating a medium between the sensation and the participant. In doing so the artist set people on a path toward subjective sensory experiences of penetration, ovulation, germination and the expulsion of being.

At first glance, the final part of the exhibition seemed to be barely connected with Kobro’s ideas and artistic visions. On the other hand, Clark based her artistic theory on constructivist thought, slowly turning toward activities involving the viewer. Eventually she developed a therapeutic method that she called Estruturação do self (Structuring of the Self, 1977) that made use of her “relational objects.” Most of them she had invented during her continuous artistic research into the surface and sensorial forms. In that sense, “relational objects” no longer had specificity in themselves, though they were constantly defined by their relationship with the artist’s fantasy.

In one sense the show could be considered an attempt to reinterpret the constructivist tradition; just as Kobro had co-created that movement, Clark used the movement as a starting point.