“The Old Man and the Musical Score” at Temnikova & Kasela Gallery in Tallinn showcases works by one of Estonia’s most important yet under recognized artists. Spanning nearly five decades of the artist’s career, the exhibition includes several new and reenacted works by Kaarel Kurismaa, whose diverse oeuvre includes painting, animation, public art, stage installations, sound, and kinetic art. As a survey of an artist who defies easy categorization, the show also maps with cartographic intensity the various artistic practices and media that have come to define Estonian contemporary art. Kurismaa’s impact on the country’s younger generation of artists is apparent too, including artists like Katja Novitskova and Kris Lemsalu, for example. His influence is not so much in terms of content, but rather in how conceptual approaches can be put into the service of pop sensibilities.

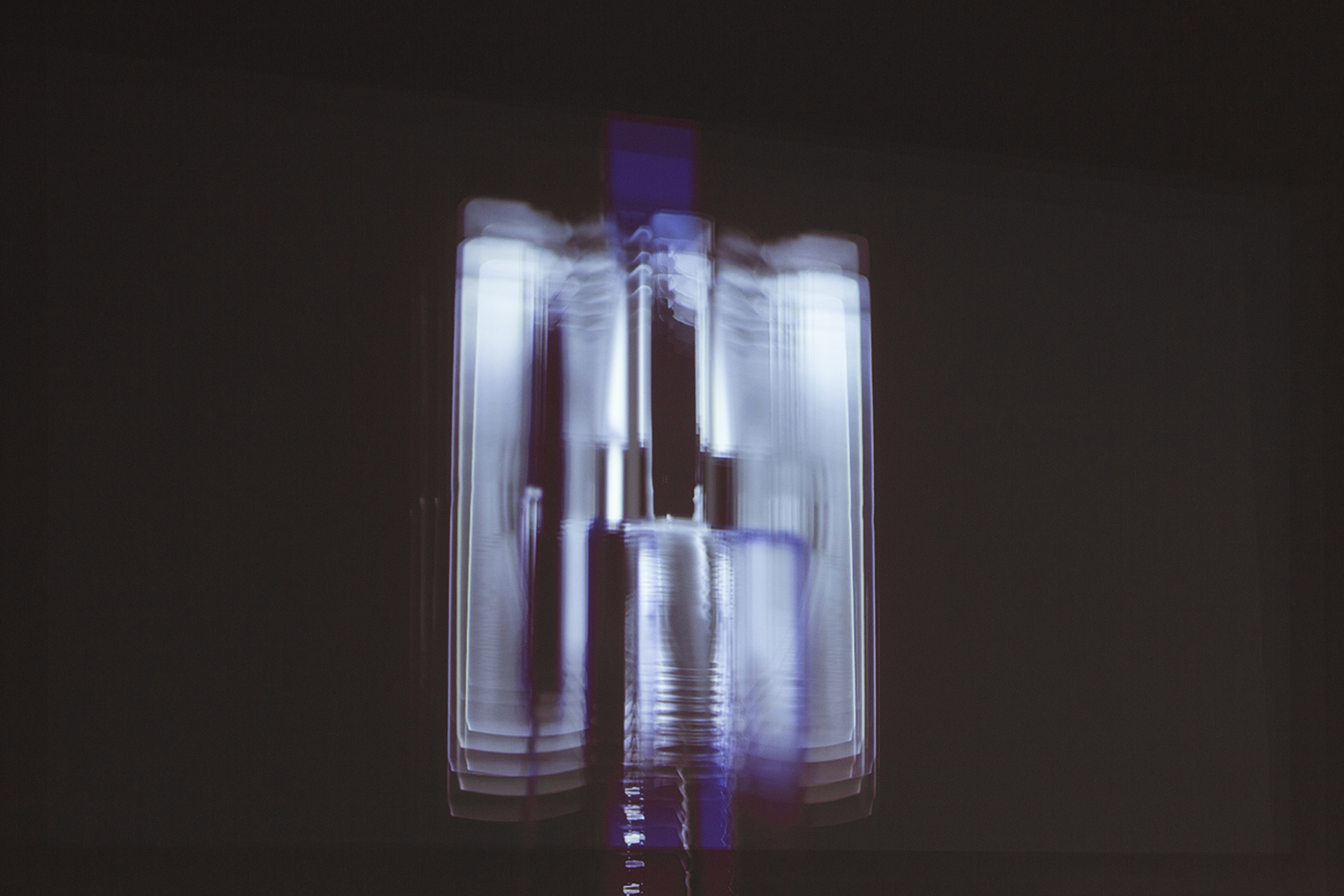

Entering the gallery, one is immediately confronted with a large, freestanding white column supporting several dolls painted white. As in most of Kurismaa’s sculptures, Amor Pillar in Retrospect (1973/2019) is made with readymade objects, in this case old celluloid dolls from 1950s Leningrad, which the artist sourced with the help of gallery staff. The work is a recreation of a similar piece Kurismaa created in 1973, a time when he was collaborating with the cult progressive rock group Mess. Though art critics at the time tended to view Kurismaa’s works within the context of Mess’s music, the cognitive dissonance his objects manifested substantially enhanced the ritualistic atmosphere of their performances.

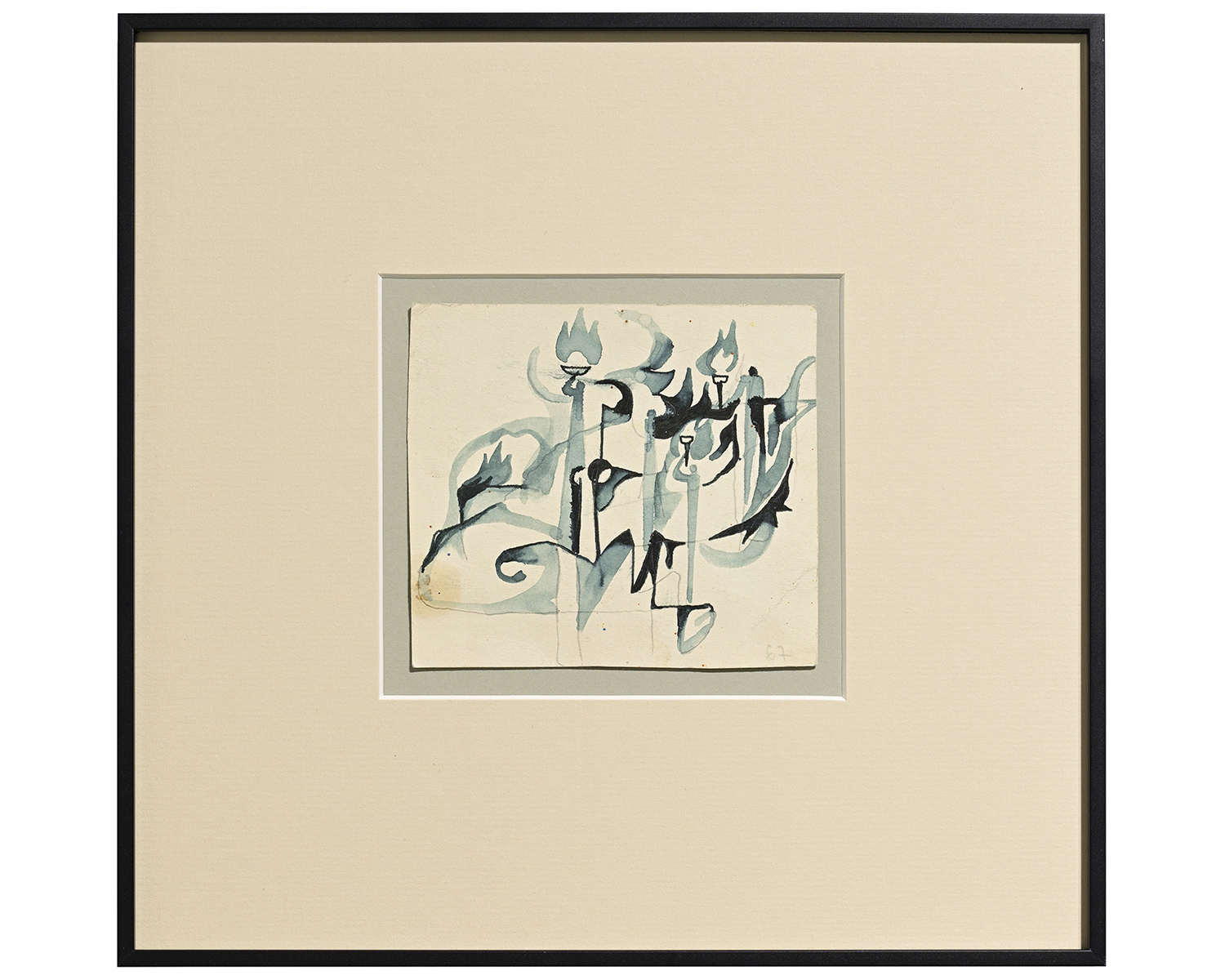

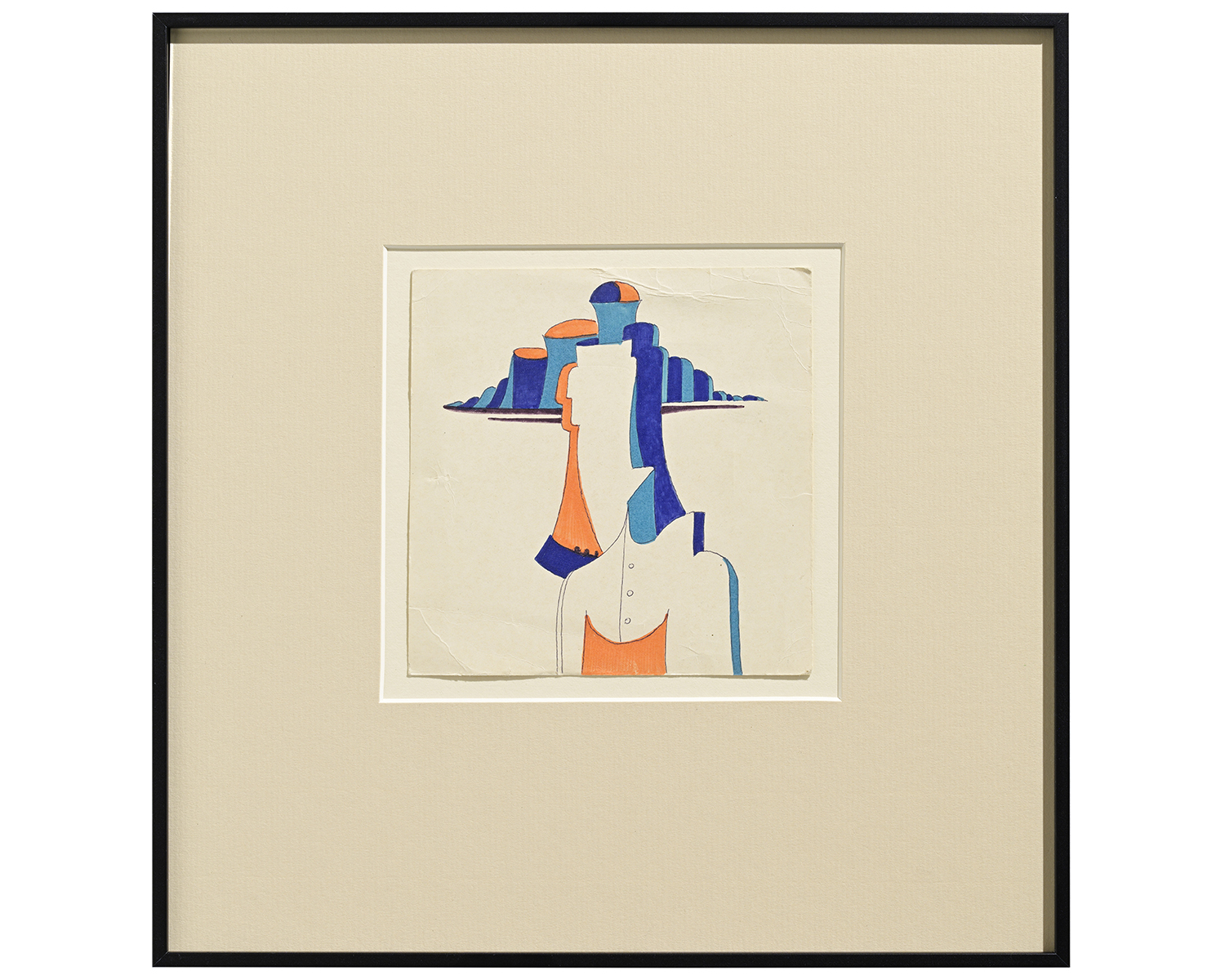

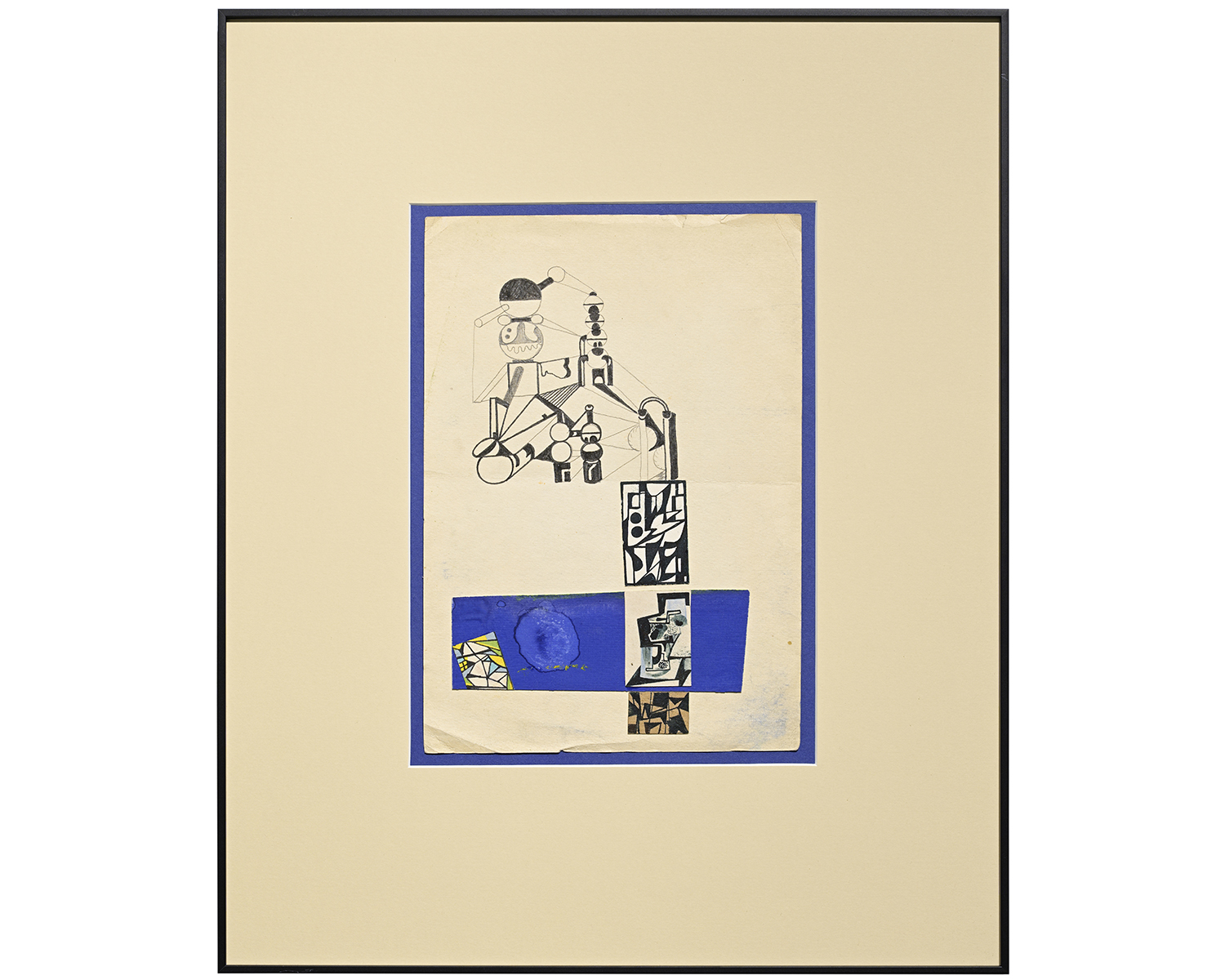

Crucially, the exhibition also includes a number of Kurismaa’s collages, works that were made after the initial wave of avant-garde music and art collaborations started to die down in the late 1970s. During this time, Kurismaa’s creative pursuits also began to shift. Toward the start of the 1980s, while Estonia was still under Soviet occupation, Kurismaa turned his attention to animated children’s films, a career path that was not altogether alien to other artists working within the Soviet Union, including Ilya Kabakov and Erik Bulatov, for example, who in addition to working as unofficial artists, made the bulk of their income during Soviet times by illustrating children’s books.

This inaugural exhibition at Temnikova & Kasela Gallery’s new space in the Kai Art Center building, located in Port Noblessner, threads together these and others elements of Kurismaa’s diverse practice, albeit in a way that unravels to reveal a sum much greater than its individual parts.