For three years Julia Stoschek has presented her private collection of video and media-based art to the general public in Dusseldorf. Last year she collaborated with MoMA P.S.1 and Performa on a research project about performance art, and she was invited to present her collection in the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg. Anna Gritz spoke with her about her beginnings as a collector, the characteristics of her collection and the challenges media art presents today.

Anna Gritz: I would like to speak about the origins of your collection. In interviews you are often compared to established collectors like Ingvild Goetz and Erika Hoffmann. I’m interested if these women were role models for you and how they influenced your collection?

Julia Stoschek: Nevertheless, there are many women in the art world that I admire, and the instigators of my work surely are Ingvild Goetz and Erika Hoffmann, but also gallerists like Barbara Gladstone. I must say that Ingvild Goetz was especially important for me early on. She supported me and offered advice on the challenges of media art. Unfortunately there still aren’t many women that have built a collection on their own, and in Germany Ingvild Goetz was the first. I admire her for her work and the high quality of her collection.

AG: For a collection to assume a specific focus, in your case media art, there seems to be a desire for articulation and order. Is this a strategy to make the endless landscape of modern and contemporary art ascertainable for you? Do you strive for an overview or some kind of cohesion in your collection?

JS: Certainly a field is determined by similar pursuits and a particular pervasion. The temporal dimension of contemporary art and media art isn’t very closely divided and many young artists orient themselves with historical positions. These relations reveal that chronology is both important and essential for the composition of my collection. In this respect cohesion is not a priority.

AG: Your collection brings together young video and media artists with established artists. Do you see your collection as an inventory of unique works or do you see it rather as an investment in artists’ future production?

JS: Basically I try to acquire whole bodies of work, key works and installations for the collection. I attempt to follow artists over a long period of time, and that includes future projects. Above all I follow two strategies; on one hand I collect the art of my generation and on the other I try to highlight a chronology, to obtain important works from the ’60s to today in order to create a bridge to the work of the younger artists in the collection. In that sense close contact with artists is essential for me, and a driving force in my approach to collecting.

AG: In the relatively short time the collection has existed you have managed to obtain an astonishing number of high quality works. Has it been to your benefit that collecting video art is still a novelty for many collectors?

JS: Actually it hasn’t benefited me. The fact that there is a very narrow market in the fields of video and media art means that it is difficult to come by good works. That results in the fact that I ‘compete’ more with the big museums, than with private collectors. Presenting video and installation work is a big responsibility; the often very high standards for the presentation of video art have to be met and that can be a challenge for private collectors.

AG: Since 2007 your collection has been housed in a former frame factory, which Berlin architects Kuehn Malvezzi converted. What made you decide to open the collection to the public?

JS: Initially I wasn’t sure if I wanted to make the collection open to the public. Egotistically, I wanted above all to make the art visible for myself, and with that came the need for space. After I secured the location I was curious and wanted to know if there was a public interest in this unusual collection. Ultimately, I decided to open the collection to visitors on Saturdays, and I’ve been surprised to see the great number of people coming to the collection every weekend since then.

AG: Do you view yourself as a kind of alternative museum?

JS: No, I see myself in no way as competition for the regional museums, hopefully more as enrichment for the local cultural landscape. I am lucky that my status as a private collector relieves me from any federal restrictions. I have neither the obligation nor the ambition to present an art-historically grounded museum education and I think that this responsibility should be left with the museums.

AG: Before you opened your collection to the public you ran « Just e.V.», a non-for-profit scholarship program for young artists. Are there any plans for the collection to continue this support?

JS: Something similar will definitely come about, but it also never really vanished. Over the last seven months I programmed live performances at the collection. This period was like a big residency, there were constantly artists housed in the artist apartment. Every two weeks there were live performances, which for the most part were conceived on site for the space. There is not yet a Julia Stoschek Prize, but artists’ support will in one form or another always be a part of the collection.

AG: Media-based art seems to have developed largely through exhibitions, with the art market lagging behind. Many works prove to be problematic in the gallery context and the black box of the theater is not always a successful alternative. On the one hand video works are more accessible through websites like YouTube, Ubu Web and tank.tv, and on the other hand their distribution is more strongly controlled by institutions like EAI or Video Data Bank. Where do you see your place in the system?

JS: When you look at the beginnings, the way video is dealt with has changed extremely. The unlimited nature of early works and the limiting of current works is a phenomenon that the art market artificially created to restrict access. These institutions take over an essential part of the dissemination of works, and I personally don’t find it at all problematic that these works are made open to the public. As a collector I feel obliged to the artists and I value the structural support of the galleries.

AG: Since 2007 you have presented your collection through a series of thematic exhibitions. For “100 YEARS,” the prominent exhibition of the last year, you collaborated with Performa and MoMA P.S.1 on a research project about performance art. How did this collaboration come about?

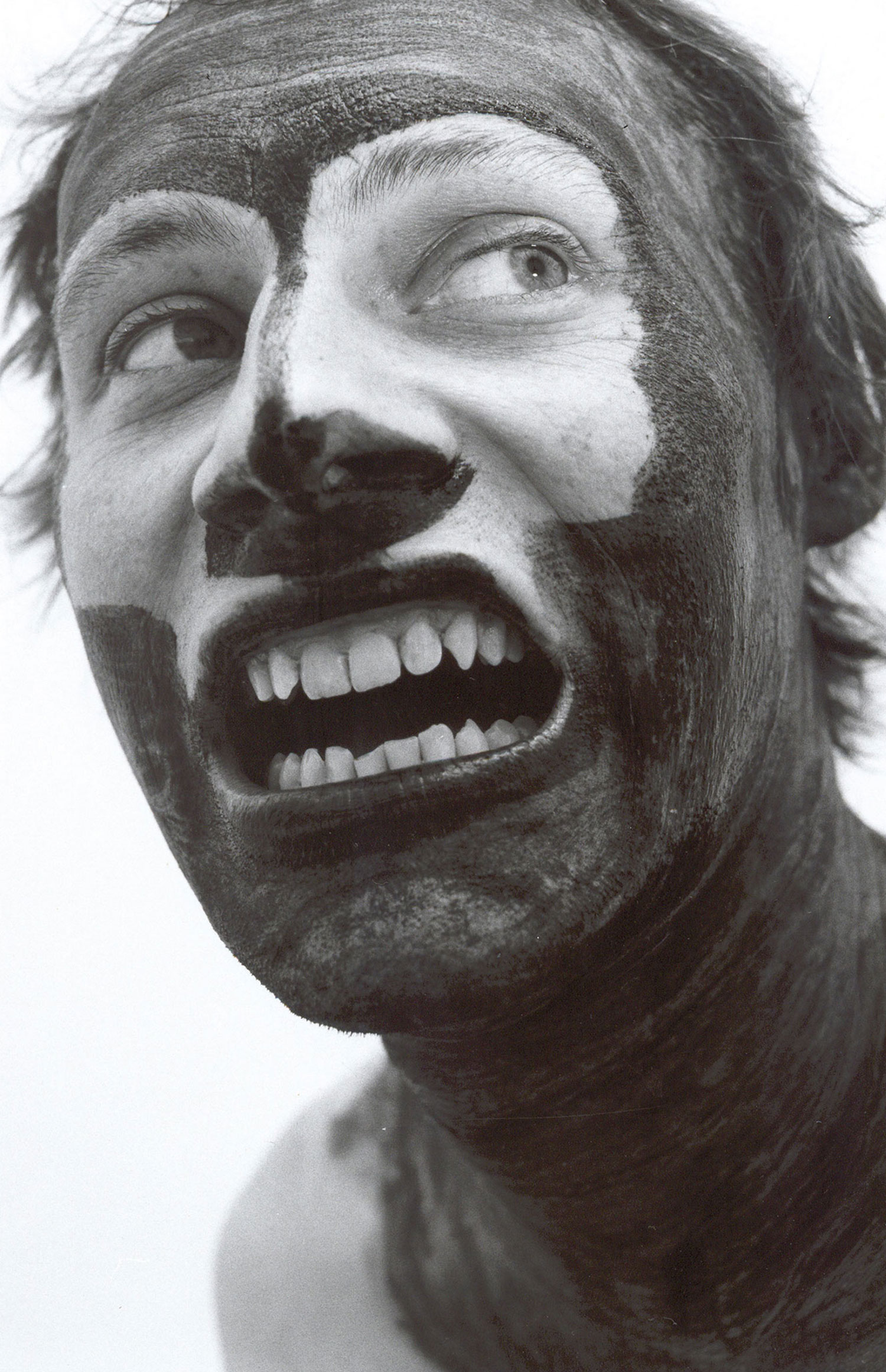

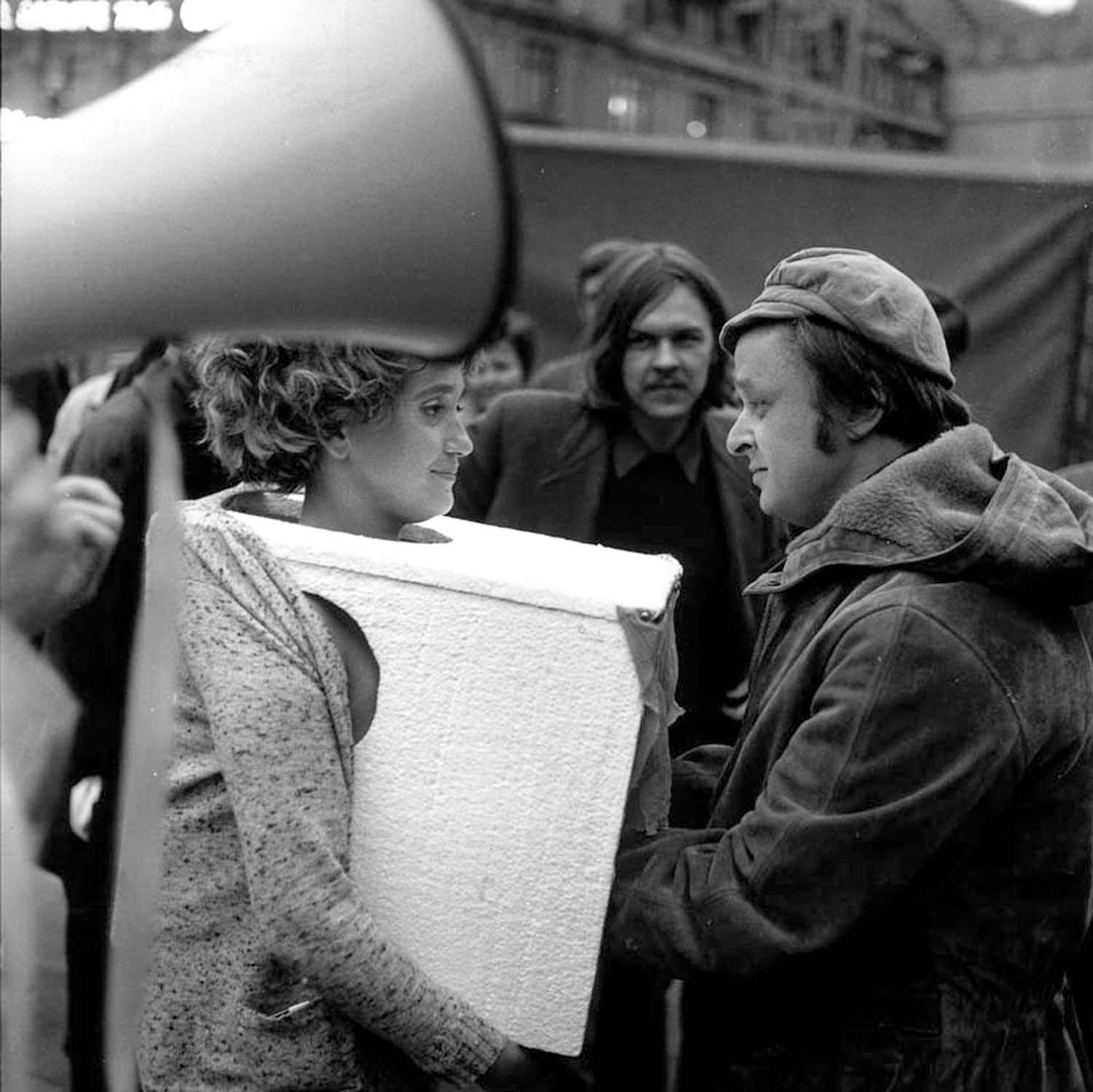

JS: It was striking that by that point there hadn’t been a historical survey of performance art. That was the point of departure for the research project that later developed into an exhibition through collaboration with curators Klaus Biesenbach (MoMA P.S.1) and RoseLee Goldberg (Performa). The Futurist Manifesto from 1909, exactly 100 years prior to the exhibition, was used as the occasion for an overview of the most meaningful actions, happenings and performances of the last century. In conjunction with the exhibition we also programmed a very elaborate performance series of contemporary and newly commissioned works by artists like Andrea Fraser, John Bock and Tino Sehgal.

AG: Could you imagine offering your collection up to guest curators in the future, like Jeff Koons did with the collection of Dakis Joannou for the New Museum?

JS: Yes, absolutely. I find it very exciting when external curators or artists look at the collection. Most recently Dirk Luckow presented the collection in the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg. It was a very stimulating experience to have someone from outside examine the entire collection and newly assemble it — an experience I will gladly pursue in the future.