During the summer of 1888 artist Paul Sérusier sojourned in Pont-Aven in Brittany, France, following the advice of artist Paul Gauguin, who was also staying there. During their stay Sérusier created the famous masterpiece Le Talisman, l’Aven au Bois d’Amour, which he brought back to Paris and showed to his fellow artists, who later on would call themselves the Nabis, which means “prophets” in Hebrew. This work of art became a magical object for the Nabis, a talisman indeed, which explains the fact that the original title could have been just l’Aven au Bois d’Amour before it was acknowledge as The Talisman — the work of art we all know. Another important fact is that the back of the painting is signed “Fait en Octobre 1888, sous la direction de Gauguin par P. Sérusier Pont-Aven” [made in October 1888 under the direction of Gauguin for P. Sérusier Pont-Aven]. In other words The Talisman was made by Sérusier under the influence of Paul Gauguin.

My attempt to frame the mysterious work of Jules de Balincourt has a lot to do with this story. Let’s pretend for a minute that Bushwick, Brooklyn is like Pont-Aven. Let’s imagine that the young and eager-to-learn Paul Sérusier is not an artist but instead an editor. Imagine a contemporary Gauguin who lives around the corner from the editor’s house; he has a place on Starr Street where he hosts events, exhibitions, screenings, parties and yoga classes. But more importantly, it is the place where he paints in his studio — the site where he makes his works.

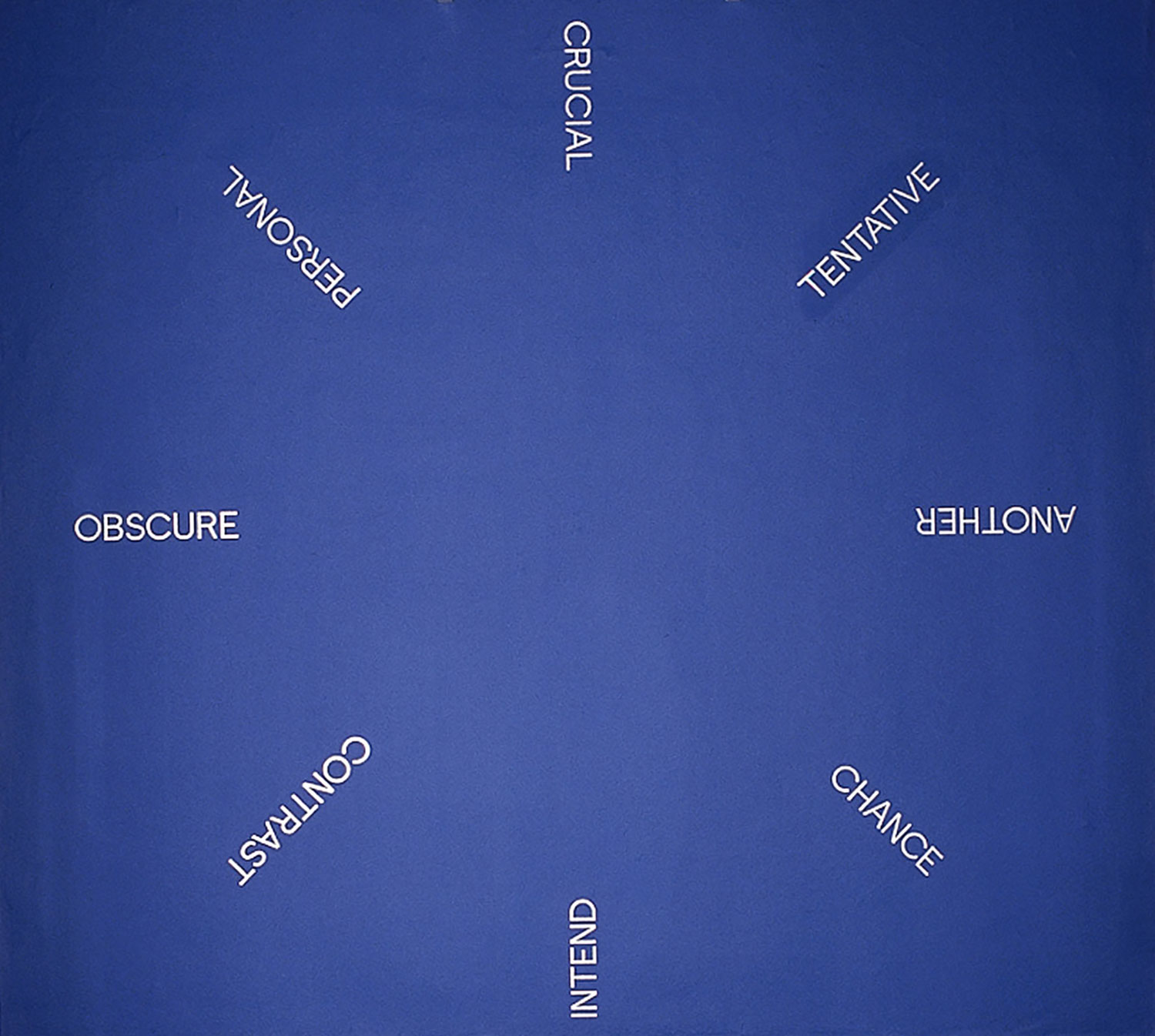

Now convince yourself, like the editor, that it is possible to write a talisman, or — to be either more clear or mysterious — that it is possible to write a text not about Jules de Balincourt but rather under the influence of Jules de Balincourt. I warn you, this is not an easy assignment. The artist refuses to give interviews or to even talk about the work, yet at the same time he unravels fragments of his imagination that the editor tries to grasp while absorbing the hallucinatory imagery of the artworks he sees during studio visits. The artist says, “It is a universe in which abstract and representational images collide and orbit one another like satellites, creating a kind of loose free-association, a non-linear narrative.” The editor is confused. He is not used to writing; he prefers to have others place their signature while he watches from his behind-the-scenes peephole. When he does write, it is all footnotes and references; he feels his voice is not authentic enough without the validation of an external source.

But he knows he cannot follow this path this time. He has to embrace these images and the person who made them; he has to smell these dazzling pictures, the vibrant palette and the iridescent colors. He tries to understand where the imagery comes from; he thinks Out of the Darkness and into the Light (2009-2010) is directly related to a motorcycle trip the artist made in India — a new Tahiti perhaps? — something he discovered from a friend who also knows the artist. He went with him to see his last show in Manhattan and was hypnotized by the aura of those paintings scattered over the walls of a famous gallery on Wooster Street. He literally saw them shining: the paintings, made on wooden panels, were mounted in such a way that the light cast colors onto the walls. The result being that when you try to look away from the imaginative narratives (or meta-narratives) of the paintings, figuration versus abstraction, you are arrested by this strip of green or red or blue shadow that surrounds the wall around the painting. The editor can’t help but think about Gauguin, who told Sérusier: “How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow. This shadow? Rather blue. Paint it with pure ultramarine. These red leaves? Put in vermilion.”

The editor also attempts to associate de Balincourt with other artists of his generation. He thinks of Dana Schutz or Christoph Ruckhäberle, or even artists from a previous generation like Luc Tuymans and Marlene Dumas for their use of images from the Internet. Or even Neo Rauch, who has surely inspired de Balincourt. But it doesn’t work that way. Then he realizes he can frame the work of the artist in relation to what he calls “craft,” stating that Jules de Balincourt has nothing to do with the pre-conceived strategies of conceptualism; his work is not like a recipe or a marketing strategy. He sees sincerity — even naïveté — in the work of this artist who doesn’t seem to have any preoccupation other than creation, the creation of astonishing images. The editor feels he can proceed this way because this is a topic he has been writing about, something he can manage, something he is comfortable with. The fact that Jules de Balincourt lived in Paris, Zurich and Ibiza, grew up in California from a French family and studied ceramics before moving to New York assures him that this is the right choice. But then he realizes the works themselves refute the word “fact” upon the very first viewing.

The editor goes again to visit the artist in his studio just around the corner. He asks how he makes the paintings, what kind of technique he uses. The artist vaguely replies. The editor asks again, just to be diligent, and then, once out of the studio and back on the street around Maria Hernandez Park, where the editor runs and prays every day, he realizes all the technical details have left him; only the images remain embedded in his mind. Lines of flashy green and red on a black background draw two human profiles encountering each other, lovers perhaps, made entirely of vibrations, Drawing Color Lines (2010); a metropolitan landscape that could be Rio de Janeiro or Los Angeles or even Gotham City reveals a bacchanal, men and women getting together in a surreal rendezvous, City Dwellers and Star Seekers (2010); a soldier, When’s My Home Leave? (2011), looks like a character from James Ensor’s masterpiece Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1888, like Le Talisman), with his eyes and mouth like pieces of lapis lazuli — it reminds the editor of de Balincourt’s more politicized works, such as If You See Something Say Something (2004), The Watchtower (2005), We Warned You About China (2007), Ambitious New Plan (2005), US World Studies (2005), United We Stood (2005) and the emblematic Holy Arab (2007); Untitled (Boys’ Club) (2011) is indeed the most photographic work and resembles a scene from The Social Network or the Dead Poets Society, to name two oxymoronic movies. Despite the political meaning of the two Native Americans in Dismounted (2010), he can’t help but thinking of horses portrayed by Marc Chagall, from The Blue Horse (1926-28) to The Red Horse (circa 1954), not to mention the onirist masterpiece I and the Village (1911). The journey terminates with the more graphic and at the same time more conceptual works: Power Flower (2010), an explosion of salmon pink, yellow and red; and Your Technology Fails Me Us You (2008), where an inextricable bundle of wires becomes a symbol of a society gone wireless.

The editor meets the artist one more time in the studio. There are works on the walls, and they start talking about how the works “radiate” both literally and metaphorically. How the artist develops his technique, how the rendering of his paintings somehow evokes the pixels of online images, or, in some cases, how the artist seems to “attack” the painting — scratching and erasing the colors and then painting the wooden panel again following some sort of visionary fury. Displayed salon style, they make the editor think of open windows on the desktop of a computer. One painting in the studio, that the artist describes as somewhere between a march, a celebration and a riot, again brings Ensor to mind. Another, a detail of a fabric pattern that seems panopticon-like (Michel Foucault, here we are) leads them to a discussion about the notion of labor and the Europeanization of American society in New York.

Toward the end, the editor realizes he fell into all the traps he tried to avoid. History, information, the legacy of visual art, they are overwhelming his imagination. He is not ready yet to take the next step, to empty his mind and let his imagination flow freely. There still so much to do and so much to forget. He realizes only now that Maurice Denis’s famous line, “Remember that a painting, before being a battle horse, a nude woman or any anecdote, is essentially a plane surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order” is really just pure poetry. And conscious of his desire to learn how to forget, he can’t help but think about Paul Gauguin, who once said, “It is the eye of ignorance that assigns a fixed and unchangeable color to every object; beware of this stumbling block.”